Politics

Tasmania’s new Parliament – challenges to our ways of thinking

It is strange that in state elections the vote count commands so much media attention in comparison with the outcome. It’s as if the journalists whose normal job is to cover football matches are appointed to organize cover of the count. They do it well – interviews with retired players, interviews in the electorate gatherings (think dressing rooms), and for the ABC, up-to-the-minute analysis from Antony Green, whose expertise would put even the best cricket statistician to shame. Public policy doesn’t get much of a look-in however.

Now, two weeks after the election, the count is complete, and we now know who will be sitting in Tasmania’s Parliament. Those turned on by the intricacies of the Hare Clark system can get the full results from the Tasmanian Electoral Commission, while those who would like to know about the composition of the new Parliament can turn to the post by ABC Hobart journalists Adam Langenberg and Adam Holmes: Who are the new and familiar faces of Tasmania's incoming parliament — and who didn't make the cut?.

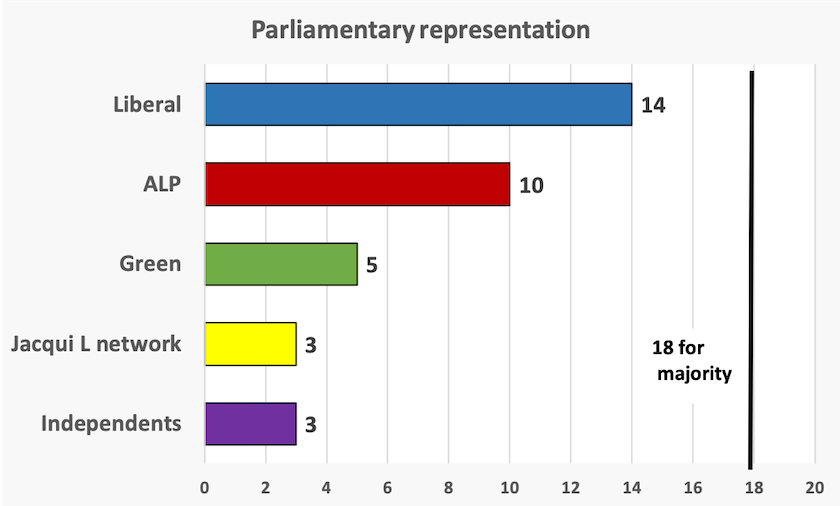

Notably, no party, or even a cobbled-together coalition of two parties, can command a parliamentary majority – 18 votes in a 35-member chamber. The parliamentary numbers are shown below:

By the conventions of Australian elections, the pre-election executive government – Jeremy Rockliff’s Liberal Party – remains in office in “caretaker” mode until a new government is sworn in. But as Adrian Beaumont writes in The Conversation it is difficult for Liberals to form government after final Tasmanian results. That’s an understatement, in view of the aggressive confidence with which Rockcliff has portrayed the outcome, as reported by The Guardian:

The new government will be steadfast in its commitment to delivering every element of the Liberals’ 2030 Strong Plan for Tasmania’s Future.

It seems that Rockcliff has not come to grips with the outcome of this election. Only 38 percent of Tasmanians voted for his party, and there is no obvious ally of his party, such as a National Party, that would bring him over the line.

If, as he claimed in calling the election, his concern is to deliver stable government, he could possibly negotiate a one-seat working majority in an agreement with the Greens. To a European that would not be unusual: Austria, for example, has a reasonably stable Christian Democrat – Green Coalition. As a claim to the legitimacy of such a coalition Rockcliff could note that the Liberal plus Green primary vote was 51 percent. Or he could go for a German-style “grand coalition” with Labor, or with Labor and the Greens.

But so embedded is the “Westminster” system in our political culture that the Tasmanian Liberals seem to be unable to escape the all-or-nothing Coalition vs Labor way of thinking.

In a later post Langenberg points out that Rockliff has done a deal with the Lambie members, to secure the political position of the Liberal government. His article – Did Lambie MPs get dud deal in Rockliff's agreement? Many seasoned politicians think so – describes a deal that seems to exclude the Lambie MPs from any effective say in policy, in exchange for a few loosely-worded commitments. That is assuming the Lambie MPs maintain tight discipline, even though members of the Jacqui Lambie Network are not tightly bound and were elected on their own, generally local, agendas.

Even if the Lambie MPs hold together Rockliff is still one vote short from a parliamentary majority. The three independents are from disparate backgrounds – a commercial fisherperson, a former trade union official, and a criminologist with a passion for health care reform. Adam Holmes has another article specifically on the three independents: Liberals winning 14 seats a far cry from 15. It brings three independents, all vocal Liberal critics, into play. All three represent important issues which put them at odds with significant parts of the Liberals’ policies. Having worked hard and taken risks to be elected they aren’t going to be ignored in the process of making laws and policies.

Rockcliff’s behaviour suggests that he doesn’t understand the election outcome, because he doesn’t understand how Australia’s political landscape is changing. He has gone for a fragile deal that might hold him in office for a while, rather than sitting down with the other 13 elected members of his party and the 5 Greens, or the 6 Lambie MPs and independents, to work out how they may form a stable government that aligns with their political principles and the revealed interests of voters. Such a process, however, is incompatible with the hard positional bargaining implicit in holding out for the “Strong Plan for Tasmania’s Future”.

Over the next year or so we will see how the political actors in Tasmania are handling our country’s transition to a multi-party democracy, away from the “two party” system. Such political transitions are rarely smooth.

Another serious aspect of the Tasmanian election is Labor’s “no contest” decision. A Politics 1 student, looking at the numbers, might suggest a “left” arrangement: Labor plus Greens to get to 15 seats – a stronger base than the Liberals, requiring only 3 rather than 4 extra votes to pass legislation. But by the convention of a government continuing in office until it resigns or is defeated, that would require a successful no-confidence motion, which would put the state governor in the position of choosing to swear in a new government or to call another election. Labor would undoubtedly shoulder the blame for the resulting uncertainty, although it may be keeping its powder dry for a no-confidence motion down the track if the government does anything too stupid.

It is also possible that Labor just doesn’t want to take office because of the state’s public finances. Wherever one looks there are unmet and growing demands, particularly in health and aged care. Tasmania’s transport infrastructure is woefully inadequate: Hobart has an extraordinarily unfriendly geography for roads and public transport, and the state’s north and south are joined by a narrow and dangerous two-lane road. The state’s school education standards are poor. Its dispersed settlement pattern makes for difficult service delivery, and there is the matter of Bass Strait.

The distribution of GST revenue through the Grants Commission process is supposed to give states equality in providing government services, but GST revenue is limited because of the low rate of GST and numerous exemptions from GST. At the same time the cost of state services is growing because of an ageing population and because health, education and policing, which account for almost two thirds of state budgets, are necessarily labour-intensive – skilled labour intensive in fact. Unless we have tax reform giving a better deal to the states, Tasmania could slowly become what West Virginia is to the USA – poor, uneducated and reactionary, but with a once beautiful landscape.

There will probably be instability in Tasmanian politics over the next couple of years. Political pundits, conditioned to the two-party system, may attribute it to essential problems with minority government and will use the pejorative term “hung parliament”, rather than the underlying problem – our national reluctance to collect enough taxation.

The EIU Democracy Index – The world and Australia are slipping

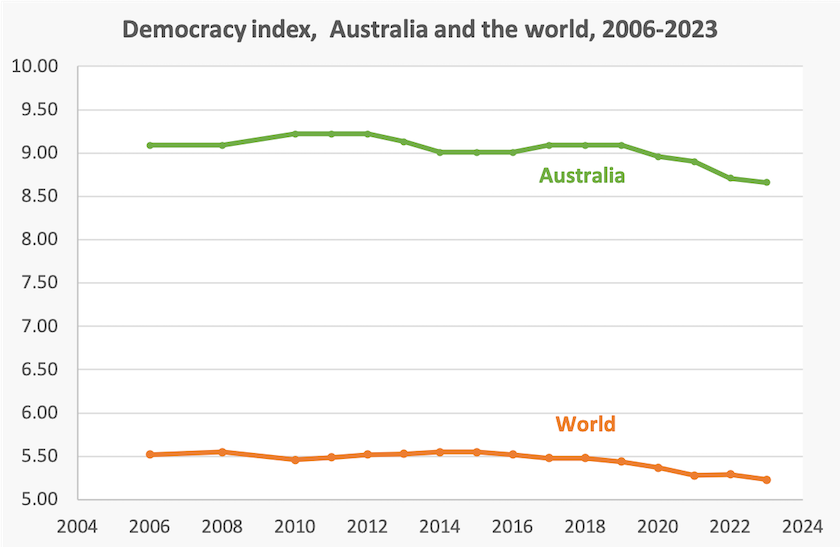

The Economist Intelligence Unit’s 2023 Democracy Index provides a snapshot of the state of democracy in 165 countries, and a time series of those countries’ scores going back to 2006. It confirms that over the last ten years there has been a significant amount of democratic backsliding.

Its democracy index, calculated for each country as a score out of ten, has five categories: electoral process and pluralism, functioning of government, political participation, political culture, and civil liberties. In turn these are broken down into sixty sub-categories. For example, under “functioning of government” one test is whether the legislature has clear supremacy over other branches of government, and under “political participation” there are assessments of the extent of party membership and other indicators of people’s engagement with and knowledge of politics.

This leads to the EIU’s definition of “full democracies” as:

Countries in which not only basic political freedoms and civil liberties are respected, but which also tend to be underpinned by a political culture conducive to the flourishing of democracy. The functioning of government is satisfactory. Media are independent and diverse. There is an effective system of checks and balances. The judiciary is independent and judicial decisions are enforced. There are only limited problems in the functioning of democracies.

Only 24 countries, in which only 7.8 percent of the world’s population lives, meet these criteria. Notably the USA isn’t one of them, having slipped to the category “flawed democracy” in 2016.

Its world map of the democracy index shows four geographic clusters of democracies – western Europe, the western Pacific from Japan down to New Zealand, north America and South America. At the other end authoritarian states are mainly in a band stretching from central and northern Africa, through the Middle East, to Russia and China, and there is a small cluster in central America.

Australia on the index – our democracy is fragile

Australia comes in at position #14, behind the Nordic countries (as usual), Switzerland, the Netherlands, Germany, Ireland and Luxembourg, New Zealand, Taiwan and Canada. As shown in the graph below, our score has slipped significantly over the last 12 years.

Australia’s scores on the EIU’s five categories show very uneven performance. We score top marks on “electoral processes and pluralism”, and on “civil liberties”. In fact on “civil liberties” New Zealand is the only other country to get a full 10.00 score. But we fall down somewhat on “functioning of government” (8.57), and particularly badly on “political participation” (7.22) and “political culture” (7.50).

We cannot see countries’ scores on the finer-grained metrics, but on political participation we probably tick the boxes on voter turnout, adult literacy and women in parliament, suggesting that our ranking is weighed down by our low party membership and general disengagement with politics.

Our low score on political culture is particularly worrying, because the criteria are to do with social cohesion, and whether people tolerate the messy processes of democracy or would prefer a “strong leader”.

These scores suggest we live in a somewhat fragile democracy, open to exploitation by a populist strongman with little respect for the institutions and conventions of democracy. So far we have shown our disappointment with the two-party model of democracy has been manifest in election of people from outside that two-party establishment, and we could be on track to a northern-European style multi-party model. But if economic conditions deteriorate, or if ruthless politicians drive polarisation further, electors may throw their support behind a strongman at the head of a party on the far right. There are people in the parliamentary Liberal Party, including Dutton, who seem to be tempted to exploit this opportunity.

Those who would like to dig into the EIU report can download it from the EIU website: Democracy Index 2023. There is no charge, but one has to provide some personal information (no financial details) to get a link to a download.

Combatting conspiracy theories and political extremism

Right-wing political extremism, such as the 2019 terrorist attack on mosques in Christchurch, and the 2022 murder of police by religious fanatics at Wieambilla, are nurtured by misinformation (getting the facts wrong), by disinformation (deliberating misstating the facts in order to mislead) and by conspiracy theories.

The Perth Extremism Research Network describes itself as “An interdisciplinary lab group … focused on research and education around issues of cultural extremism and neoreaction”. It is funded by the US Consulate in Perth and Curtin University.

In a 4-minute session on the ABC’s AM – How do you combat extremism? – Isabel Moussalli interviews three members of the network, who explain the ways they are reaching to the public to alert people to the existence of disinformation and conspiracy theories, to explain how these theories arise, and to suggest ways of countering them. They include the warning that attempts to engage in rational argument or to correct falsehoods can result in people hardening their attitudes. They also warn that many young people are attracted to these movements.

The network’s website has a number of educational resources including PowerPoint slides and reading lists. They cover the ideas underpinning conspiracy theories, including the “post truth world”, “great replacement theory” and other forms of “white” extremism such as the “Alt-Right”, the “manosphere” (strategic misogyny), and the “sovereign citizen” movements.

Immigration: 50 ÷ 18 738 = 0.00267, a very small number

Over the last few months up to four boats have landed asylum-seekers on our remote north-west coast. The most recent boat carried 10 people, and the two or three previous boats carried about 40 people in total. All were quickly taken to offshore detention.

Based on those small numbers and the speed of relocation, whatever people think about our indefinite detention system, they have to admit it’s effective. In fact one could argue that the government is over-attentive to boat arrivals, in view of the fact that 18 783 asylum-seekers arrived by air last year.

Of course we know that’s not how the politics of asylum-seekers works. Writing in the Saturday Paper Mike Seccombe covers the politics of asylum-seekers, in an article explaining how Immigration Minister Andrew Giles is handling this issue. It’s a positive assessment of a minister who has had to confront many challenges, including from the High Court. As Giles says to Seccombe, “Immigration broadly plays into a reactionary form of populism”.

The Saturday Paper article is paywalled, but Seccombe covers the same ground in an interview on the Schwartz Media 7am Podcast. Complementing Seccombe’s analysis are observations from the Asylum Seeker Resource Centre, who note the distress of those who have come by boat, and the moves made by authorities to cut them off from communication. This is in an article by Erin Parks and Rosanna Maloney: Asylum Seeker Resource Centre with human rights concerns as Nauru detention centre fills with boat arrivals.

Towards the end of the 7am interview there is a discussion about the government’s rush to get the deportation legislation through Parliament. Former Immigration Department Deputy Secretary Abul Rizvi, in a post on Pearls and Irritations, explains the real reason Labor is rushing through immigration powers. It’s an inelegant and brutal solution to a difficult problem, but that’s because the government feels it has little political room to manoeuvre in immigration. The most recent Essential poll finds there is little opposition to the government’s deportation policies: older people and Coalition voters (they tend to overlap) are particularly likely to support these policies.