Our road to destructive inequality

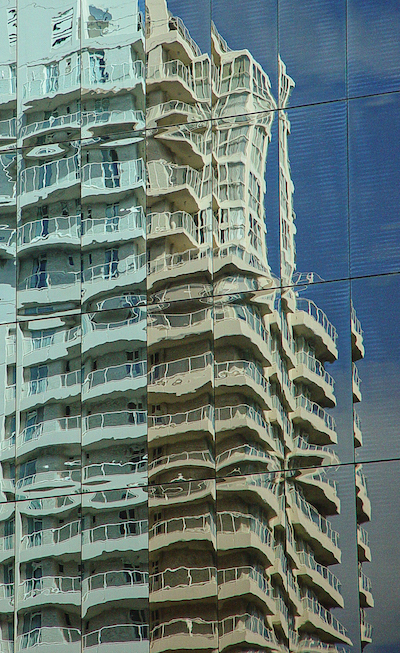

Inequality is manifest in many domains. It is most serious in housing, where it is becoming intergenerational.

An economist, a playwright and a journalist on Australia’s economic structure

Unless we address structural weaknesses in our economy, our future is one of falling living standards for most Australians, widening inequality, and a fracturing of the social contracts that hold our country together.

The impediments to structural reform are political, most notably the way Coalition politicians, in government and in opposition, opportunistically resort to scare campaigns to thwart reform.

The economist

Ken Henry has been once again stressing the urgent need for structural reform, without which we are headed for an “intergenerational tragedy”. He describes our low wage growth economy as a “catastrophe”, and warns that “the operation of our democratic system itself is at stake” in a 9-minute ABC interview: We are breaking the 'golden rule' of economic policy. That golden rule is an obligation for each generation to hand to the following generation the opportunity to thrive, but we are breaking that rule, manifest most clearly in housing unaffordability. We have a “colonial economic structure”, rather than a structure that can ensure our prosperity in a competitive world.

Henry’s main message is about the need for tax reform, as it has been since 2010 when he presented the Tax System Review, which the government largely rejected – not because it disagreed with his recommendations, but because the Coalition opposition, the mining industry and the Murdoch press were lined up to mount a fear campaign, and they did it successfully in relation to the resource rent tax.

Writing in The Conversation Peter Martin summarises Henry’s ideas and warnings in the context of the way we talk about government budgets: How about this time we try, just try, to report on budgets and tax differently?. That is, to disregard “what’s in it for me?” issues and to ask what it does for structural reform.

Henry warns that our tax base is shrinking in relation to our needs. We load responsibility for paying taxes on labour, normal business profits and real-estate transactions, while inadequately taxing consumption, wealth, land, windfall profits and economic rents, and failing to collect revenue through user charges (particularly road user charges) and through taxing negative externalities (most CO2 emissions).

The playwright

David Williamson occupies a half-hour session on Late Night Live, talking about his most recent play The Great Divide. To Williamson our economic failure is manifest in the divide which sees many Australians unable to afford a home. This is in the context of Australia, once one of the world’s most egalitarian societies, having become one of the rich world’s most inegalitarian societies.

Australians want something better, but even though the present government is on the right track, progress is glacially slow, because it is scared, burnt by the failure of Labor’s reformist agenda in the 2019 election (which researchers find wasn’t responsible for their loss). Australians hoping for something better put their hopes in the election of a Labor government (a theme Williamson developed in his 1971 play Don’s Party), but when Labor is elected people feel let down by its caution.

The journalist

An illusion for the young

Ian Verrender, the ABC’s business editor, has a post Has the great Australian dream of affordable home ownership turned to a nightmare?. As the title suggests he’s writing about housing affordability. For most of the twentieth century the median house price in Australia hovered around 6 times GDP per capita. That would be around $600 000 now. But at the turn of this century house prices took off, and the median house price is now about 11 times GDP per capita. And there are signs house prices are taking off again.

As Henry points out, high house prices, in a market where many people cannot afford to buy, worsen intergenerational inequity. Those who are securely housed can help their children enter the market. Young people who don’t have such support cannot get into housing and will not be able to help their own children into house ownership: that’s why it’s intergenerational. Verrender reports that the bulk of first home buyers last year were those who were able to draw on the bank of mum and dad.

Economists suggest that once a housing bubble has developed, those who own houses seek to keep the bubble inflated, because of the apparent wealth benefit of having a house with a high market value. Rationally, the market value of your house should be of no concern to you; its value lies in its comfort and convenience, and that doesn’t change. Perhaps it may matter if you plan to move, but in all probability the market value of the house you want to buy has moved in tune with the house you’re selling. Once people stop and think, the value of their own houses should be of no concern.

That logic holds unless you’re a property speculator, in which case to you a house is a financial asset. That transformation of housing to become a financial asset has come about, in large part, because of permissive rules on capital gains taxes and the taxation treatment of interest payments (“negative gearing”).

The wreckers: the Coalition

Henry and Verrender hint at the political constraints impeding economic reform but are not explicit. Williamson, who speaks more freely, refers to Morrison’s “bullshit” and “bluster” in running a scare campaign in the 2019 election.

For the most part journalists and academics politely duck the question of responsibility for scare campaigns that block economic reform, falling back on phrases such as “both main parties” or “politicians of all stripes”, or simply saying “it’s political”.

That’s an unfortunate construction because it implies that so long as we have a democracy, reform will never happen.

That approach, which implicitly regards the two established parties as undifferentiated competitors, as is the case in most sporting contests, ignores important established differences between those parties. The Coalition, even by its own definition, is a conservative party, largely dedicated to preserving the established order. Labor has always been the party of economic reform. That’s not to judge the comparative morality of the parties: this division is established in the conventions of two-party democracies. Labor/Labour/Social Democrat/Socialist parties always have the hard task of proposing reform, while parties on the right can take the easy approach of opposing.

In Australia’s case, with very few exceptions, scare campaigns against reform have been instituted by Coalition parties, their backers in the Murdoch media, and the mineral sector. In office Coalition governments rarely engage in economic reform (unless one classifies privatization as “economic reform” rather than the plunder of public assets). In election campaigns they don’t hesitate to run scare campaigns against reforms proposed by Labor, and in apprehension of such campaigns Labor disempowers itself by promising not to carry out reforms.

This is a time-honoured tradition of right-wing parties, but it makes no sense in the longer run, for it only leads to general disillusionment, political disengagement and to an impoverished and divided society. Is that what Dutton, Tehan, Ley, Taylor and others in the hard-right flank of the Liberal Party really want? Or are they just too arrogant, and too fixated on keeping Labor out of office, to realize it?

Australians’ views on housing policy – we want governments to do something

Please fix it

The latest Essential poll has a set of questions on our attitude to housing and housing policy.

On the primary role of housing, 91 percent of respondents believe housing should be “a basic human right that everyone should have access to”, or that it should be “the foundation for vibrant neighbourhoods and communities”. Only 9 percent believe it should be “a vehicle for growing personal wealth”. When asked what role they believed housing is actually playing, however, 35 percent of respondents agree that it has become “a vehicle for growing personal wealth”.

On these questions there is hardly any discernible difference between the attitudes of Coalition and Labor voters.

So why, one may ask, is the government so frightened to deal with negative gearing and capital gains taxation for “investment” properties? Surely if they supported these reforms they would not lose support.

But, as demonstrated in the Voice campaign, the Coalition is adept at taking an issue about which people agree, and turning it into a scare campaign. Such a campaign would find ready support from those who have managed to prosper from the property bubble with so little risk or effort – real-estate agents, property developers, mortgage brokers, insurers, and of course the sacred “mum and dad” investors. (At the same time those who do something useful, making a tangible contribution to housing – builders – are struggling or going broke.)

Respondents are questioned on the performance of governments – federal, state and local – on housing. We’re not very impressed with any tier of government. Unsurprisingly those who own “investment” properties are more satisfied than those who don’t, and renters are particularly dissatisfied. Surprisingly, however, homeowners with a mortgage are a little more satisfied with governments than those homeowners who don’t have a mortgage, a finding that goes against the general talk about interest rates and mortgage stress. But there may be other factors at play, because those who have paid off mortgages are generally older.

There are more specific questions on support for possible housing policies. For each of the five options put forward, some on the supply side, some on the demand, there is at least 50 percent support. The impression one gains from the responses is that people simply want governments to do something.

The most telling responses are to the question “Would you like to see house prices continue to rise, reduce, or stabilise?” Only 15 percent of respondents would like to see prices rise. and 40 percent would like to see prices reduce. One might expect that homeowners with a mortgage would like to see house prices rise, but only 21 percent of those respondents wanted to see prices rise.

This brings into question the judgement of journalists writing on property websites, who write positively on rising house prices, in the same way as financial writers write positively on a rising share market. They are revealing themselves as spruikers for property developers.

In the same spirit there is a set of three statements on the housing system generally. Only 9 percent of respondents believe the system is “largely working well and does not require change”. The other 91 percent are almost evenly split between those who think it needs minor change and those who believe it is “broken and needs to be fundamentally rethought”. There are predictable differences depending on respondents’ age, voting intention and whether they own an “investment” property, but these are not large enough to negate the conclusion that nearly everyone is unhappy with the housing system.

Land, the strong driver of wealth inequality

Over the last two weeks the ABC’s Gareth Hutchens has been re-introducing us to the ideas of Henry George, the economist who, in the early twentieth century, advocated for better taxation of land, including exploitable natural resources.

While basic economic texts refer to three factors of production – land, labour and capital – land is left out of consideration in the dominant discipline known as neoclassical economics (and Marxist economics even leaves out capital).

In the final installation of his three-part series Hutchens asks Why did land disappear from some economic models?.

It shouldn’t be left out, because as any Australian who has title to a piece of real estate knows, the market value of land has been on a long-term upward trajectory. Hutchens summarises Thomas Piketty’s work Capital in the twenty-first century. Piketty, he says, “detailed specifically how the private ownership of land was connected to wealth accumulation, and how certain management of land (and the incomes that derive from it) can be a long-term driver of wealth inequality”.

Hutchens goes on to explain how Henry George’s ideas lost traction in Australia. They certainly didn’t appeal to the squattocracy, and because George believed strongly in free trade, they didn’t appeal to protectionists – a case of guilt by association. The economic establishment, although it does not reject the idea of the three factors of production, finds it too hard to fit land into their models because they have built up a whole interrelated framework around labour and capital.

As an example of this omission, think of the way economists refer to productivity – either in terms of labour productivity or total factor productivity, which brings in capital but not land.

Hutchens’ explanation of the difficulty of bringing land into the basic economic model is reminiscent of the intellectual conflicts described by Thomas Kuhn in his 1962 work The structure of scientific revolutions. The guardians of a discipline have so much sunk investment in the models they have built that they not only have difficulty in accepting challenges to the discipline’s basic framework, but they also actively fight off such challenges, dismissing the challengers as cranks or “left field”, and intensifying their efforts to assert and defend the discipline’s established theories.

Those who argue for the inclusion of land in the economic model are not cranks, Hutchens points out. He mentions the late Trevor Swan, the world-renowned foundation professor of economics at ANU, after whom the Solow-Swan economic growth model is named, and more recently Ross Garnaut, who defended Henry George’s ideas in the 132nd Henry George Address last year.