Politics

State elections and by-elections: the Coalition’s continental drift

It will be some time before we know the outcome of Tasmania’s election in terms of seats won, agreements, deals and possible coalitions. But we do know it’s a disaster for the Coalition.[1]

Wait on. Didn’t they win more seats than Labor? Didn’t opposition leader Rebecca White concede defeat when she said Labor would not try to form a government? Is not the Liberal vote, at 37 percent, clearly ahead of Labor’s 29 percent?

That’s all correct, and it indicates that Rockliff ’s Liberal government will hold office. But in terms of voter support it’s a miserable outcome for the party.

A 12 percent loss in primary vote is a disaster for any party, particularly for a governing party that has been doing nothing worse than providing the usual mediocre and opportunistic administration characteristic of Coalition governments, and when the Labor opposition has been uninspiring. It’s also the latest instalment of a national adverse trend for the Coalition.

The national picture: a decade of Coalition loss

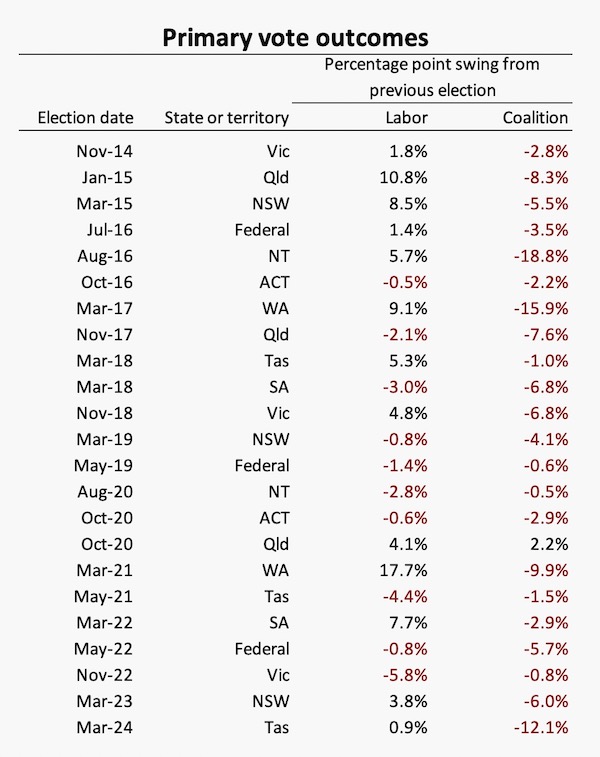

Many readers will have seen the table below, showing primary vote outcomes in federal and state elections since 2014. The only change is another line at the bottom, showing that over the last 10 years, in 22 of 23 federal and state elections, the Coalition’s vote has fallen.

Counter to this interpretation Coalition supporters may point out that the LNP did very well in recent by-elections on Brisbane’s western fringes, with a 19 percent swing in Ipswich West and a 13 percent swing in Inala. These swings, if repeated federally, could put Labor’s hold of Oxley and Blair in doubt – two of Labor’s only five seats in Queensland. And opinion polls are pointing to the LNP returning to office in Queensland in the next state election.

These Queensland figures would be heartening to Dutton, Canavan and other Queensland powerbrokers, but from a national perspective they confirm that the Coalition is becoming a regional party – a Queensland party, or more specifically a Queensland minus Brisbane party. Note that the only Coalition gain shown on the table was in Queensland in 2020.[2]

In the rest of Australia that isn’t Queensland the Coalition holds only 33 out of 121 seats.

Trouble in South Australia

While political nerds were captivated by the ABC’s election count from Hobart – including Erica Abetz’s inane portrayal of the count as a landslide endorsement for the Liberal government – they may have missed the Liberal’s miserable showing in the South Australian Dunstan by-election.

Dunstan lies in Adelaide’s prosperous inner east and northeast suburbs – “teal country” is the easiest way to describe it. Labor won the seat from the Liberal opposition: this is one of those rare occasions when a sitting government wins a seat from the opposition in a by-election. The two-party outcome was a swing of 2 percent to Labor, but Labor and Liberal both lost primary vote – Labor lost 3 percent, Liberals 7 percent, most of which came as an 8 percent gain for the Greens. In South Australia the Liberal Party is in a bitter internal conflict between moderates and the far right. There is a similar conflict in Victoria.

If the Liberals lost ground in Tasmania, who gained?

We know that most of the Liberals’ 12 percent loss went to the Jacqui Lambie Network (7 percent), and a little to the Greens and Labor (1 percent each). Independents, including the two who left the Liberal Party over the Hobart stadium issue, did well, but probably not well enough pick up a seat.

The regional distribution of this loss is extraordinary. Tasmania has five multi-member electorates, three of which (Barton, Bass and Lyons) could be classified as rural (if that’s not offensive to the 70 000 people who live in Launceston) and two of which (Clark and Franklin) are in and around Hobart. Up to now the Liberals were doing well in the rural electorates, with primary votes between 52 percent and 60 percent, but these seats have seen swings between 12 and 22 percent away from the Liberals, mainly to the Jacqui Lambie Network. This loss in rural electorates must be of concern to the National Party in Victoria and New South Wales.

As for the two urban electorates, the Liberals lost ground in both. That includes a swing of 8 percent in Franklin, comprising mainly Hobart’s outer suburbs and semi-rural settlements, and a loss of 5 percent in Clark, the more urban electorate. Labor too lost ground in Franklin, to the Jacqui Lambie Network.

It is telling that the Greens, who might have been expected to do well in view of Premier Rockliff’s promise to tear up the native forest agreement, achieved only a tiny swing. Is it that in Tasmania the Greens are now seen as part of the old political establishment?

Tasmania’s use of a proportional representation system (Hare Clark) in each of its five seats helps explain why, in terms of seats won, independents, Greens and the Jacqui Lambie Network have done well. In a seven-member electorate 12.5 percent of the vote secures a quota.But even if Tasmania had 35 single-member electorates, rather than 5 electorates with 7 members, it is doubtful if the main parties would have done much better, because the combined Labor plus Coalition vote was only 66 percent.

Those who want to dig into election figures can follow William Bowe’s Poll Bludger, where he has specific links to the Tasmanian election and to the Dunstan by-election.

Speculations

So conditioned are our media to the idea of a “Westminster” two-party system that many journalists are likely to be taking stress leave as those the Tasmanians have elected develop some governing arrangement. (Perhaps they could take that leave visiting mainland Europe’s thriving multi-party democracies.)Many are still talking about a “hung parliament” with its implication of instability, rather than a “multi-party parliament”.

Some may attempt to classify winners and losers on a “left” – “right” spectrum, but that doesn’t go far.

It’s also rather meangless to talk about who won the contest, because while the Liberals may have enough seats and may be able to cobble a deal to avoid a vote of no confidence, they will not be able to implement their platform.

The same would hold for Labor had they tried to form a coalition. As Saul Eslake points out in an article by the ABC’s Adam Landenberg, – Economist rebuke for Tasmanian Liberals, Labor over failure to address dire economic forecast during election campaign – whoever forms government will have to deal with their unaffordable promises. If “winning” is about securing a few jobs for parliamentarians, then the Liberals have won. If “winning” is about political power, neither of the two old parties has won. That’s democracy.

On the ABC Insiders David Speers interviews three political specialists about the Tasmanian election, and possible federal implications. (The ten-minute session starts at five minutes, after a discussion of the government’s decision to give $5 billion in foreign aid to one of Europe’s de-industrialized backwaters.) Robert Hortle and Richard Eccleston of the University of Tasmania have a political interpretation of the outcome, including some guesses about the immediate course of Tasmanian politics.

Martyn Goddard, who knows Tasmanian politics well, has some observations on his Policy Post: In their last redoubt, the Liberals lurch further to the right – and oblivion. He points out that even if they can win the support of members from the Jacquie Lambie Network, to pass legislation the Liberals still need support from other members, who tend to be to the left of Rockliff. If, as is possible, Eric Abetz takes over from Rockliff, the premier will be even more isolated from the rest of Parliament. Goddard’s general observation of Tasmainan politics: “Tasmania urgently needs a government that has some idea about why it exists”.

The ABC’s Ashleigh Barraclough has an explanation of the workings of minority governments, including a reminder that Tasmania has had minority governments in the past, and that federally we had the Gillard government: Tasmania has elected a hung parliament. So what does that mean, and how do minority governments work?(A pity she can’t break from that word “hung”.)

Klaas Woldring has a positive interpretation in his Independent Australia article Tasmanian election result a challenge to improve democracy, where he writes “More likely – and hopefully – this is the beginning of a shift in political thinking and practice in the sense that governments can be permanently formed as coalition governments”.

The most challenging outcome is that voters ignored the Liberals’ scare campaign about minority government. Over time voters have been able to observe minority governments in action, and predictions of chaos have not eventuated. They can see at a federal level that independents and minor parties, free from hard policy “positions” with which large parties bind themselves, can use their power to achieve outcomes that break through these binds and serve the public interest.Policy wonks, journalists and political strategists may have to go through the hard task of examining their conditioned mindsets.

1. That’s the Liberal Party in this instance, because so far the island has been able to quarantine itself from the blight of the National Party. ↩

2. The LNP lost the 2020 election but a collapse in the One Nation vote saw much of the hard right vote come back to the LNP. ↩

Opinion polling

The publication of political opinion polls leads people to ask “whose winning – the Coalition or Labor”.

On that question the answer is that the latest polls from seven well-regarded polling outfits (Essential, Newspoll, Resolve Strategic, Morgan, Freshwater, Redbridge and You Gov) suggest that in comparison with the 2022 election Labor’s support is down by about one percent, the Greens support is up by about one percent, and the Coalition’s is up by about two percent. Figures for each pollster can be found on William Bowe’s Poll Bludger site.

But that may not be the right question at a time when support for both traditional parties is low and is falling. Those same polls show the total Labor plus Coalition plus Green support to be only 80 percent, in spite of an inevitable bias in national polling to understate support for small parties and local independents.

One of the survey questions in the most recent Essential poll is about satisfaction with democracy. “Satisfied” comes in at 32 percent, equal to “dissatisfied”.Satisfaction was high in May 2022, possibly as a result of our having seen off the corrupt and opportunistic Morrison government, but it has fallen back since then.Unsurprisingly Labor supporters are more satisfied than Coalition voters – their side won the election.

The pessimistic interpretation is that we look around the world, noticing the political failures in countries like the UK and USA where progress on important issues is stalled by populists’ exploitation of democracy’s weak points, and become disillusioned.

The more optimistic interpretation is that people are responding to the only democracy most Australians know, the “Westminster” two-party system. It’s going through a slow and painful death, and there will be the occasional remission, but if we get it right we may be on the way to a more inclusive Nordic-style multi-party democracy, embodying the best of Australian traditions.

Religious discrimination laws

Glen Innes Convent

We don’t know what’s in the government’s possible legislation on religious discrimination, but we do know what the Australian Law Reform Commission had in mind when the Attorney General tabled the report he had commissioned in 2022: Maximising the Realisation of Human Rights: Religious Educational Institutions and Anti-Discrimination Laws. For those unattracted to 469 pages of legal opinion, there is also a summary report.

That summary makes it clear that the Commission is dealing with two separate issues. It states that while it is concerned with discriminatory practices in “educational institutions (including schools, tertiary institutions, theological colleges, and other educational institutions)”, it is specifically concerned with the “extent to which they should be excepted from obligations generally imposed on all persons:

by the Sex Discrimination Act and, to some extent, the Fair Work Act, not to discriminate against another person on the grounds of that person’s sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, marital or relationship status, or pregnancy.[3]

and

by the Fair Work Act not to discriminate in the employment or the prospective employment of another person, on the ground of religion”.

Anyone unfamiliar with the path of Australian politics over the last five years would reasonably believe that resolution of the first issue is simple, while the second raises some difficult questions.

On the first, most would agree that in a secular democracy no employer, education institution or government should be at all concerned about the sexual practices of consenting adults. Removal of the exception for religious institutions should be easy to wave through Parliament.

The second raises many tricky issues, some of which are discussed by Mark Fowler, an associate of law schools at Notre Dame and Queensland universities, speaking on the ABC’s Religion and Ethics Report: Religious concern over discrimination act. Although Fowler does not mention the term, some issues to which he refers relate to what are known as “reaction qualifications”. That is discrimination on the basis of the reaction by third parties: would the government reasonably rule out sending a homosexual woman on a diplomatic posting to Iran? Would an Islamic school rule out hiring a Jewish teacher, on the basis that families may withdraw their children?

Civil rights lawyers generally hold that concern over others’ reactions do not provide grounds for exemption from anti-discrimination legislation.

That’s before we get to the issues where people’s strongly-held religious beliefs may contrast with the religious belief upon which the school is based. Would a Catholic school be comfortable hiring a Lutheran to teach the history of the Reformation? We may dismiss such a concern on the basis that a professional teacher’s own religion would have no influence on the way he or she teaches, but to look at the same issue from a more secular perspective, would a non-religious school hire a known creationist as a biology teacher? It’s hard to find a clear rule, particularly when it comes to possible influences on the minds of school-age children. Universities by contrast should have more latitude.

These are all difficult issues, but the ABC’s Tom Crowley suggests that the Commission’s report has “dealt with only the LGBT discrimination-in-schools aspect, not the religious-discrimination aspect”: Government hears back on religious schools review, but its own plans are still unclear.

Maybe this territory is too hard for the Commission, because it cannot be addressed without going into the whole question of why our governments have allowed religious groups to set up their own schools, and why they are allowed to operate single-sex schools.

Also discrimination on the basis of belief raises questions about border security policy. We do a good job at keeping out people with violent intent, but should we also discriminate against people who hold strong beliefs that are incompatible with the established traditions of a liberal secular democracy and who may want to change the nature of that settlement? Muslims who adhere to Wahabi teachings, Catholics who belong to the Opus Dei cult, the Exclusive Brethren?

It’s not a new issue – Socrates grappled with it 2400 years ago. Some may suggest we should resolve it categorically, while others may say it’s best to allow it to drift, allowing courts to decide from time to time on the boundary cases of what constitutes reasonable discrimination.

But as Crowley and others point out, it’s actually the question of sex and gender discrimination – the one that should be easy to resolve by applying the principles of secular democracy -- that’s been causing so much political stress.

It’s because the rights of transgender people have become a sticking point in earlier attempts to resolve the issue. Luke Beck of Monash University takes us through the history of the political conflict in a Conversation contribution: Why are religious discrimination laws back in the news? And where did they come from in the first place?. In another Conversation contribution Archie Thomas of the University of Technology, Sydney, and Jessica Gerrard of the University of Melbourne remind us that homosexuals are also discriminated against by the same carve-out for religious schools: Before the 1980s, Australian teachers could be banned for being gay. A new report wants to protect them at religious schools too.

Equality Australia reports that LGBTQ+ discrimination is endemic in religious schools around Australia. they provide evidence of actual cases of discrimination, and they find that many schools, particularly Catholic schools, are not forthcoming about their policies and practices. Ghassan Kassisieh of Equality Australia provides a short summary of the report on the ABC. (3 minites)

It’s evident that a substantial majority of parliamentarians would like to see laws passed that would prohibit education establishments from discriminating on the basis of “sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, marital or relationship status”.But what stymied the Morrison government in 2018, when, with support from the Labor opposition, it attempted to present such legislation, was the opposition from a few people on the hard right of the Coalition who didn’t want to see transgender people afforded the same rights as homosexuals and others defined in the LGBT alphabet. As a result the government withdrew the bill rather than face an open party dispute.

If the Albanese government presented such a bill today it would probably get through Parliament, even if the Coalition, in a show of unity, opposed it. But Albanese says he wants “bipartisan” support – a notion which, in itself, shows a certain contempt for our Parliament of several parties. Presumably he fears that if he passes the legislation without support from the Coalition, Dutton would focus on the transgender issue, presenting Labor as the party that directs its energy to woke concerns.

The broader homosexual community is disappointed and unimpressed, as are most independents, the Greens, and Liberal MP Bridget Archer.

3. To keep it readable, this quote omits more complete names and references referring to particular Acts.↩

Gender discrimination: women in Hobart put the case for men’s clubs

An installation at Hobart’s Museum of Old and New Art (MONA) has brought gender discrimination to the fore. It’s a highly-decorated enclosed space known as a “ladies lounge” to which only women are permitted.

It raises the issue of gender-separated places, covered in an article by the ABC’s Maani Truu: Necessary sanctuary or blatant discrimination? The decades-old battle over women-only spaces.

Although the Hawke government passed the Sex Discrimination Act in 1984, it provided carve-outs for religious institutions (see the above post), for sports, and for clubs.

Australia still has “gentlemen’s” clubs in most capitals – the Melbourne Club perhaps being the most well-known. In a 2015 Women’s Agenda article Lucia Osborne-Crowley described these establishments: The state of men-only clubs in Australia? Alive, well and popular. She found them to be frequented by Australia’s “richest and most powerful men”.

Are they really places for Australia’s richest and most powerful men, or are they more like enclosures for a threatened species – those who once were the richest and most powerful? This question arises in Peter Temple’s novel Bad Debts, where Jack Irish’s misconceptions about the Melbourne Club are corrected:

Jack, I think you're out of touch. You're still stuck in the days when the Melbourne Club ran this town. All those pompous arseholes who owned factories and insurance companies and played the market. All went to Melbourne Grammar or similar and basically silly buggers who didn't like Jews or Ities or other kinds of wogs. Otherwise reasonably harmless twerps. Their day's gone, Jack. They woke up one day and found the real money was in property development. Residential subdivisions. Hotels. Shopping centres. Office blocks. And most of the people making the money didn't give a shit about joining the club.

But their membership hasn’t fallen, and only a few, most noticeably Brisbane’s Tattersall’s Club, have caught up with the spirit of the 1984 Act by opening membership to women. Progress towards breaking down these last bastions of gender separation has been painfully slow.

It’s unfortunate therefore that a group of women have thrown their weight behind MONA’s provocative statement, by demonstrating outside the Tasmanian Civil and Administration Tribunal to show their support. If they had the political nous of the suffragettes, or of the women who chained themselves to men’s bars to civilize our hotels, they would have stormed and occupied Hobart’s male-only Athenaeum Club, in support of Anti-Discrimination Commissioner Robin Banks and author Heather Rose who tried to break the club’s discrimatory practice.

Do these women realize that in defending “women’s only” spaces they provide justification for a continuation of gender separation, not only in clubs, but also in informal arrangements where men come together – the drinks after work where men caucus, hunting and fishing gatherings where men congregate to reinforce one another’s misogyny, men’s sheds that epitomise traditional gender roles? Do they realize that gender-separated societies are harsh and violent, not only against women and children, but also against men who seek civilized company? Afghanistan provides the most horrifying example.

Or, perhaps they do understand those consequences, and seek a return to the old order, in line with the movement known as “fourth-wave feminism” – a movement that makes about as much sense as a group of South African Zulus coming together to urge a return to Apartheid.

Political donations

Reform of political donations is shaping up as a conflict – not between the Coalition and Labor, but as a conflict between Coalition and Labor on one side, and on the other side Greens, independents, and people seeking more meaningful choice when they come to vote.

The Grattan Institute’s Kate Griffiths has a short article – At last political donations are on the agenda – setting out the current rules for federal elections, and urging two basic changes – real time disclosure, prohibiting donation splitting to circumvent caps. The government seems to be on board with these basic reforms.

The more difficult issue relates to spending caps. At first sight one may believe that tight spending caps would favour independents competing with well-funded political parties, and work against rich populists such as Clive Palmer, but it’s not that simple. Griffiths demonstrates that spending caps could actually put independents at a disadvantage.

The ABC’s Tom Crowley has an informative post on the politics of electoral reform, explaining why independents and others seek a donations cap but not an expenditure cap, because an expenditure cap could make it hard for new independents to run for office, in competition with incumbents: Gloves off on electoral reform as government accuses crossbench of hypocrisy.

Crowley’s post also mentions progress on truth in election advertising, a measure that would presumably encourage parties to direct their efforts to policy arguments rather than to mounting scare campaigns. Presumably any legislation would be based on the existing provisions in South Australia. One difficulty is the need to find an adjudicating or fact-checking body: the Australian Electoral Commission does not want to be put into this role. (Anyone who has followed US politics over the last four years would understand the need for bodies administering elections not to be associated with any statements that may be seen as partisan.)

The most recent Essential poll finds that there is strong support for electoral reforms, including ensuring that political advertisements are truthful (72 percent), real-time disclosure of donations (64 percent), and caps on donations (61 percent). Increasing public funding to candidates, however, finds few backers. There’s little discernible difference according to voting intention, but there is a strong age gradient: older Australians are much more in favour of electoral reform than younger Australians. For example, while 87 percent of people aged 55 and over favour truth in political advertising, among those aged 18 to 34 support is only 53 percent. Worrying.