Economics

How economics must change

Criticisms of economics and economists abound. Some are based on misunderstanding, partly because economists aren’t adept at explaining their work to the public, and partly because many people have a visceral reaction to numbers. Some comes from those who advocate a completely different framework of economics, such as Marxism.

It’s harder for the profession to ignore criticism when it emerges from inside the profession, from one with the standing of Angus Deaton – a recipient of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences.

Tony Ward, a reader of these roundups, has drawn our attention to Deaton’s observations on the failure of economics, published in the March 2024 edition of the IMF magazine Finance and Development, alongside the contributions of another five prominent economists who also offer their ideas on how economics must change.

Of those six contributions Deaton’s is perhaps the most challenging. Not because it’s radical – it isn’t – but because he addresses issues in plain sight that the profession has not wanted to confront, because they go to some of the basic assumptions upon which economics is based.

He brings in the hard question of power in markets, noting that power asymmetry is a normal condition in markets and not just some infrequent aberration from the textbook competitive market model. In this regard he notes that the decline of unions “is contributing to the falling wage share, to the widening gap between executives and workers, to community destruction, and to rising populism”.

He questions the established idea “that economists should focus on efficiency and leave equity to politicians or administrators”. But as he says, those measures to compensate for resulting inequities “regularly fail to materialize, so that when efficiency comes with upward redistribution our recommendations become little more than a license to plunder”.

He does not dismiss the benefit of efficiency. Rather he sees the task for economists as what engineers know as “constrained optimization”. That is, to maximize efficiency within the constraints of achieving social justice and preserving individual liberty, to re-cast Keynes’ prescription. Go for efficiency but don’t break these binding rules.

Along the way he confesses to having re-considered and questioned the benefits of free-trade and immigration.

The ABC’s Gareth Hutchens summarises and discusses Deaton’s contribution to the IMF’s debate: Economics is in “disarray”, having placed efficiency before ethics and human well-being, says Nobel laureate. He puts Deaton’s article in the context of his broader work, including his 2020 book (co-authored with Anne Case) Deaths of despair and the future of capitalism, and his 2023 book Economics in America: an immigrant economist explores the land of inequality.

One of the other five economists in this call for change is Diane Coyle, of Cambridge University, who goes back to the basic model of the competitive markets. She writes:

The theory states that market outcomes are the best that can be attained—if certain key assumptions hold.

Needless to say, they rarely do.

One of the most unworldly assumptions of that model is that the marginal cost function faced by producers is U-shaped. That is, production can expand until it gets to a point where diseconomies of scale start to outweigh economies of scale. This assumption holds pretty well for coffee shops in Melbourne or rice-growers in Vietnam, but it is simply not the case for industries with zero, or very low, marginal costs of production, such as social media firms and telecoms. Engineers, for whom scale economies are everyday fare, have never understood economists’ fantasies about rising marginal costs. Nor do young people who observe a world where for many products, as demand rises prices fall as scale economies and innovation play their part. For them the economists’ model makes no sense.

Nor do those outside the profession understand how economists can callously accept the supposedly value-free idea of “Pareto optimization”, which posits that economists should not make any normative assumptions about different people’s enjoyment of costs and benefits. That is they cannot assume that an intervention making an unemployed single mother $1000 better off while taking $1000 from Gina Rinehart is an improved outcome, but they can assume that an intervention making the unemployed single mother $10 better off, while making Gina Rinehart $1000 better off, is an improvement, because no-one is worse off. Hence the notion that “a rising tide lifts all boats”, a notion that ignores inequality. The pseudo-science of what economists call the “Edgeworth box” is a moral cop-out dressed up in the language of dimensionless graphics.

In the same edition of Finance and Development, although not in the same series about how economics must change, is an article by Dani Rodrik, one who has always held a qualified view on the benefits of globalization and a sceptical view about neoliberalism: “Addressing challenges of a new era”.

He asks whether the economics profession was responsible for neoliberalism. (Or did the right-wing zealots of the world find a convenient theory in the economics textbooks and latch onto it?) He notes the claim that neoliberalism with its reliance on markets, private incentives and globalization was the principal driver of the vast reduction in global poverty. But perhaps this is a post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy, because China and India broke most of the rules of neoliberalism in their successful growth models. “The original sin of the neoliberal paradigm was the belief in a few simple, universal rules of thumb that could be applied everywhere”, he writes. The economic problems of our time – climate change and the erosion of the middle class – must be addressed with well-designed policies targeted at these problems, while providing meaningful and productive employment:

Addressing the problem of good jobs will require policies that go beyond those of the traditional welfare state. Our approach must put creation of good jobs front and center, focusing on the demand side of labor markets (firms and technologies) as well as the supply side (skills, training). Policies will have to target services in particular, since that is where the bulk of employment opportunities will be generated in the future. And they must be oriented toward productivity, since higher productivity is the sine qua non of good jobs for less-educated workers and a necessary complement to minimum wages and labor regulations. Such an approach calls for experimentation with novel policies – the development of what are effectively industrial policies for labor-absorbing services.

There are many more critiques of economics in this edition of Finance and Development. One of its articles is a short graphical summary of the World Happiness Report, posing the often-asked question whether there is a tight relationship between GDP per capita and happiness. Quite a few countries rank more highly on happiness than on income, but for some, such as Singapore, high income hasn’t done so well in generating happiness. Australia ranks at #12 on happiness – behind the Nordic countries and New Zealand, and just ahead of Canada, Ireland and the USA. (More on the World Happiness Report next week.)

Australian economists’ conservative reaction in response to the US Inflation Reduction Act

In the US what may be the government’s biggest move in industry policy since the New Deal, is called the “Inflation Reduction Act” – presumably a name that helped get it past Republican Congresspeople who didn’t realise it appropriates almost $US400 billion to clean energy through tax breaks, grants and loan guarantees.

Because in Australia we too are seeking to become internationally competitive in green products and technologies it raises the question about how we should respond with our own policies to promote an energy transition. It’s one of the oldest issues in economic policy – whether or not to match or even outdo a competitor’s interventions.

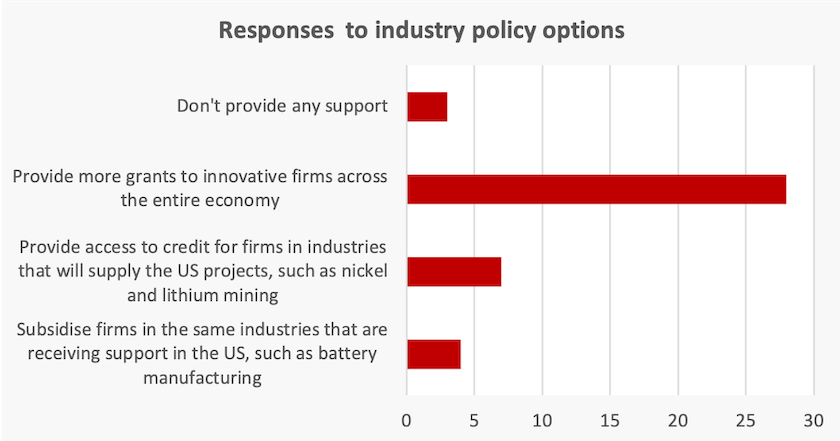

Peter Martin reports on a survey of 44 leading economists designed to elicit their views. Four options were presented ranging from doing nothing through to an interventionist industry policy, as in the USA.

He presents the results of this survey in a Conversation contribution: Economists say Australia shouldn’t try to transition to net zero by aping the mammoth US Inflation Reduction Act.

The propositions and responses are shown in the graph below.

Possibilities which might have been considered in an earlier time when Australia was going through a stage of national development, such as the Commonwealth establishing and running a battery factory (think Commonwealth Serum Laboratories, the Commonwealth Aircraft Corporation) were not on offer. Nor were more mild forms of industry policy such as the Commonwealth taking shared equity in ventures, as suggested by Mariana Mazzucato. (See last week’s roundup.) Judging by the responses to the questions actually put, it is likely that no one would have gone for these more adventurous options, involving government risk-sharing and entrepreneurialism.

Our economic establishment has become rather conservative.

Electricity prices short term and long term

Short term – Australian Electricity Regulator’s draft determination

After peaking in mid-2022, the wholesale electricity price – the price you would pay if you lived next door to the power station and bought electricity at high voltage without transformation – has been falling. By the end of 2023 the wholesale price in the National Electricity Market had fallen from highs between 20 and 35 cents per kWh in mid-2022, down to 3.4 to 7.9 cents per kWh, according to the Australian Energy Regulator (AER) report for the fourth quarter in 2023.

Does this mean there should be a similar fall in retail prices from next July, when the AER sets retail price ceilings for the coming year?

Yes, there should be some fall in prices, but not to the same extent as the wholesale price has fallen for two reasons. First, prices tend to vary seasonally: prices are higher in winter because there is more demand, and less sunlight for domestic and industrial-scale photovoltaic systems. Second, there are other parties in the supply chain before it arrives at your lights and power outlets. There is the transmission and distribution system – high and low voltage lines, transformers and switching stations, and “retailers” who smooth out the minute-by-minute fluctuations in prices and sell electricity to you at a contracted price. That’s why even if the wholesale price is in the order of 10 cents per kWh, you’re paying 25 to 35 cents, in addition to a daily connection fee.

On Tuesday the AER produced its draft “default market offer” for 2024-25, indicating that most residential consumers can expect nominal price falls in the order of 7 percent, and businesses can expect slightly more substantial falls. There is some variation by region and by supplier, which means for some customers there could be a small price rise. These details are provided in the AER document Default Market Offer (DMO) 2024–25 Draft Determination. A final determination is expected in May.

One reason the price fall is modest is that payments to the privatized and corporatized transmission and distribution companies will rise. To quote the draft determination:

Network cost increases are being driven by inflation and interest rate rises along with under recovery of revenue due to milder weather conditions over the last year [they are paid on the basis of kWh transmitted] and, for New South Wales, the development of the NSW Roadmap.

You’re paying for this as well

This generosity to the “poles and wires” companies results from the industry-friendly regulatory regime that sets the price paid to these companies – essentially the price paid for delivery from the power station to your lights and power sockets. The companies should be only lightly touched by rises in interest rates, because they tend to have a portfolio of loans, some of which pre-date recent rises. As for weather conditions the model upon which prices are set already includes a significant premium for risk – “gamma” in the jargon of business finance. Had the ideologues not privatized the networks, consumers would be enjoying much more substantial price falls.

Tony Wood of the Grattan Institute explains the draft determination, with a focus on the effects of prices and bills, in a Conversation contribution: Finally, good news for power bills: energy regulator promises small savings for most customers on the “default market offer”.

The ABC’s Daniel Mercer and Tom Lowrey have a short article on the AER draft – Winners and losers as energy regulator outlines mixed bag of power price changes – and on ABC Breakfast there is an 11-minute interview with Clare Savage, chair of AER: Electricity ceiling prices sets to drop.

Savage gives the usual advice to consumers concerned about their electricity bills: they should shop around for the best offer. That’s sound individual advice, but while not many are on the default market offer, only about 20 percent of customers do shop around. It’s lousy advice because of its effects on the other 80 percent, who cross-subsidize the shoppers – retired nerds who have time to construct spreadsheets and track the market. And if everybody shopped around no-one would benefit: that’s the “fallacy of composition” at play: “good for one, bad far all”. Electricity is a basic, undifferentiated commodity for which the only variable of concern to consumers is the price. It would be better to set simple basic tariffs, saving all consumers the costs of “confusoply” and eliminating these cross-subsidies.

Savage’s more useful advice is for everyone who can get their hands on finance, and whose housing is suitable, to go for panels and batteries. It’s a much surer investment than housing, and it’s tax-free.

Long term – stick to renewables because nukes are expensive and take a long time to build

It is hard to understand the Coalition’s continued insistence that Australia’s reduction in GHG emissions should be through replacing existing coal-fired plants with nuclear reactors. The economics are clear: they’re more expensive than renewables, even when the costs of firming are included, and they would take many years to come on stream. There is a political argument about how long it would take to get reactors up and running. The Coalition has suggested it would be about 10 years, which the RMIT-ABC Fact Check aligns with their finding of about 9 years, but that estimate does not “time for planning, design or changes to regulation, which would be necessary in Australia”.

The Coalition points out that most other “developed” countries have nuclear energy. That may be true, because nuclear energy made sense 30 or 40 years ago. Countries that have old plants do well to keep them running at low marginal cost. But the case for building new ones generally falls down on economic grounds. The Coalition refers to Canada’s plan to build more nuclear plants. That makes sense in a country with very cold and relatively dark winters. But in case the Coalition hasn’t noticed, Canada generally lies above the 49th parallel, which defines most of its border with the USA. Hobart, our southernmost large city, is at 43 degrees.

Nuclear’s cost disadvantage has been made clear in the CSIRO’s GenCost: Annual insights into the cost of future electricity generation in Australia, and is confirmed by major businesses in the energy market. See, for example Giles Parkinson’s piece in Renew Economy: ”Prohibitive:” Australia’s biggest energy consumers and producers say no to nuclear, but is Coalition listening?

The ABC’s Ian Verrender provides an additional reason why companies are unenthusiastic to build nuclear power plants in Australia: we can do better selling uranium to countries that really need to rely on nuclear (think of Canada once again and of all those places with cold or sunless winters). Also, in a world where interest rates have gone back up to around their historical levels, the discounted cash flow (DCF) value of nuclear plants is further disadvantaged in comparison with renewables, becaue they take so long to come on stream and to generate a positive cash flow: Why big business would rather send uranium offshore than build nuclear plants in Australia.

All of that hasn’t stopped the Coalition from asserting, without revealing sources, that the CSIRO’s GenCosthas been “largely discredited”. (The passive voice is a marvellous way to make such a statement, because there is no requirement to put an agent in the sentence).

Parkinson has another article on Renew Economy explaining that the Coalition’s claim has been so misleading and potentially damaging to Australia’s scientific reputation that the head of CSIRO, Douglas Hilton, has published an open letter asserting the organization’s independence and professionalism: CSIRO defends GenCost – and science – as Coalition and Murdoch go nuclear against key institutions. Parkinson quotes extensively from Hilton’s letter, which you can read in full on the CSIRO website. Hilton does not mention Dutton or the Coalition, but it’s clear to whom he refers where he writes: “As Chief Executive of CSIRO, I will staunchly defend our scientists and our organisation against unfounded criticism”.

It’s hard to know what’s behind the Coalition’s nuclear stance – a stance so strong that they’re prepared to undermine the reputation of Australia’s premier research institution. The charitable interpretation is that they’re simply ignorant, most of the members of the parliamentary Coalition with an understanding of science and economics having lost their seats in 2022. The less charitable interpretation is that they’re trying to thwart Australia’s energy transition, possibly because of their connections with the fossil fuel industry.

Aged care funding – more than a fiscal convenience

Last week we covered the recommendations of the Aged Care Task Force. Its main recommendation concerned funding. Rather than funding the increased cost of aged care through a Medicare-style tax levy, as recommended by the Commission on Aged Care Quality and Safety, the task force recommended that increased costs in aged care should be funded by higher contributions from users of aged care residential and in-home services. Aged Care Minister Anika Wells seems to be set to accept this recommendation.

This could be seen as a pragmatic response in pre-budget time, but in a discussion on Saturday Extra – Government backs a shift in aged care policy – demographer Liz Allen of ANU sees it as a fundamental shift in government policy. The government is tacitly acknowledging that it should not go on asking taxpayers, most of whom are of working age, to go on supporting older Australians, many of whom are enjoying a raft of benefits paid for by younger Australians.

Allen sees the government’s decision as a move in an ongoing “intergenerational warfare”. It’s a minor concession to younger people. Previous governments, mainly Coalition, have been fearful of the backlash from older Australians when developing policies, but a Labor government need not fear, because most older voters are rusted-on Coalition supporters. It is hard to imagine that there would be enough Labor or Green older voters who would switch to the Coalition in reaction to this move. And as Allen reminds us, there is a demographic shift in voting: as present cohorts of voters age they are not shifting to the Coalition. This is unlike the situation in earlier times when support for the Coalition rose as people’s aged.

The 11-minute discussion goes on to general and serious issues about intergenerational equity, particularly the role of inheritances in widening and solidifying class divisions.