Taxation – beyond Albo’s tweaks

Taxes are the price we pay for civilization

Oliver Wendell Holmes

Can the old political parties bring real tax reform to the agenda?

There are two distinct views on the political possibility of further taxation reforms following the government’s amendments to the 2019 Morrison package.

One is that because the decision was through a process that risked depleting the government’s political capital, the possibility of more comprehensive tax reform has receded. Conversely, because it exposed the stupidity of political promises and confirmed that people prefer good public policy to hard positional stances, and forced Dutton to put forward some ideas, it opens up the possibility of comprehensive tax reform, as recommended by the Henry Review in 2020. Maybe, even the idea of a “broken promise” has been broken.

In her established style of having two bob each way, Michelle Grattan touches on both possibilities in her Conversation article Albanese’s Stage 3 rework invites a wider tax debate the government doesn’t want to have.

The politics and economics of tax reform are covered in the National Press Club discussion by Allegra Spender and Richard Denniss – two well-informed people involved in politics and uninvolved in competitive partisan wedging. They agree strongly that while the government’s amendments improve significantly on the final stage of the Morrison package, they address only one small aspect of our tax system, all of which is in urgent need of overhaul.

The political theory of tax reform is that when there is a proposal to reform any specific tax, even if it benefits a majority of the population, those who feel disadvantaged by the reform will mobilize to oppose it, while those who would benefit do not rally in support of it. That is in line with the findings of behavioural economics, which confirm that people react much more strongly to possible losses than to possible gains. Also it is easy for a political party or an interest group to mobilize around that discontent, amplifying it with lies and misinformation.

That’s why economists see the path to reform in terms of developing a package. Each part of the package will have winners and losers, but the net effect of the whole package should be benefits all around, or at least without any losers – a “Pareto improvement” in economists’ terms. This was the theory underlying the Henry Review, and is essentially the message of others who have been calling for reform ever since, including Spender and Denniss.

How much are we paying for civilization?

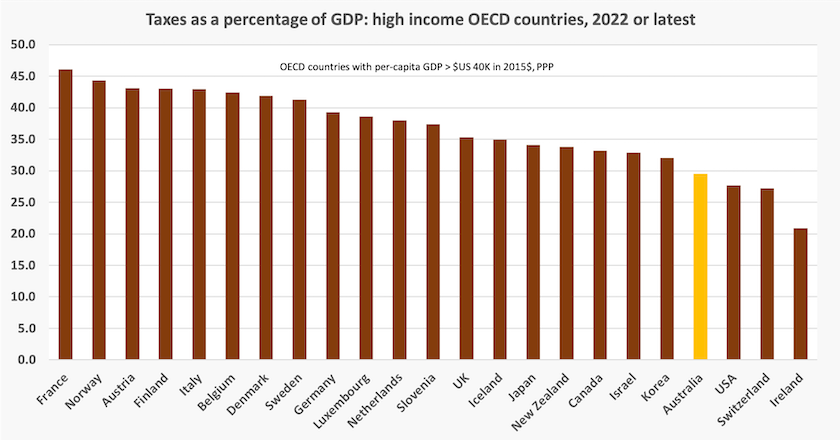

The dominant view on tax, as revealed in the regular Per Capita Tax Survey, is that Australia is a “high taxing big government country”. In fact, among high income “developed” countries, we’re a nation of skinflints when it comes to funding the collective good – the common wealth or civilization to use Wendell Holmes’ frame.

The graph below presents Australia’s taxes, collected by all three levels of government, in comparison with other high-income OECD countries.[1]

The comparative tax landscape is a little more complex than can be captured in one graph. For example Ireland, the country at the extreme end of the graph, is a tax haven. People often compare our taxes with America’s: at 29.5 percent of GDP our taxes are higher than theirs of 27.7 percent of GDP. But the US government runs a budget deficit of about 6 percent of GDP: if they ran a fiscally balanced budget, as the present Australian government is doing, they would have to collect taxes at about 33 percent of GDP. And even that figure does not account for the cost of private health insurance, which is essentially a privatized tax, costing about another 6 percent of GDP.[2] Similarly Switzerland, another country that appears to have low taxes, also relies on private health insurance. If you’re thinking of migrating to the USA or Switzerland, understand that after paying for health insurance, which is almost as inescapable as official taxes in those countries, you will finish up with less disposable income than if you choose to stay in Australia.

On the other hand, most other high-income countries have social security systems that are partly taxpayer funded. While we have the age pension, we also have a superannuation system funded by compulsory private contributions: that’s our main privatized tax which is probably higher than private contributions in other countries’ social security systems.[3]

Even taking superannuation into account however, we are one of the most lightly taxed of all high-income “developed” countries.

Allegra Spender and many others make the point that in comparison with other countries Australia is highly dependent on personal income tax to raise public revenue. That is correct: about 40 percent of our tax revenue is from personal income tax, while the average in high-income OECD countries is about 30 percent.[4] The USA is another country with high reliance on income tax: in that country, in addition to federal income tax, many states have their own taxes.

Richard Denniss makes the mathematical point that the main reason income taxes are prominent in our mix is because we don’t collect much tax from other sources. He mentions, for example, the absences of a comprehensive resource rent tax and of a carbon tax. Denniss is right: our income tax as a proportion of GDP is 11 percent, about on the average for all high-income OECD countries.

Perhaps our reliance on income tax contributes to the impression that we’re a high-tax country: it’s the most visible of our taxes, appearing every fortnight on most workers’ payslips. It is notable, however, from the Per Capita surveys that over the last ten years the proportion of people seeing Australia as a high-taxing country has fallen from about 50 per cent to 40 percent. Maybe campaigns bringing to public intention tax avoidance by big businesses is starting to re-shape public opinion.

The point where Spender, Denniss and most other non-partisan observers would surely agree is that we are heavily reliant on income tax collected from working-age Australians, while we apply only light taxes on income from financial wealth, and on financial wealth itself, including the assets accumulated by well-off retirees. There is something lopsided when a country taxes retirees more lightly than it taxes workers.

The politics of broad reform

Such is the political environment around tax reform, an environment shaped by successive Coalition scare campaigns, lies and misinformation, that the government is unlikely to move on negative gearing, capital gains tax, inheritance taxes, income from superannuation accounts, or trusts. As for a comprehensive package of tax reform, it would soon be derailed by journalists and lobby groups calling on the government to rule things out – GST, wealth taxes, road user charging.

The government’s amendments to the Morrison package were easy, however. Thanks to a better-than-expected fiscal outcome, including the revenue benefits of bracket creep, it has been able to implement a Pareto outcome: no-one is seen to lose.

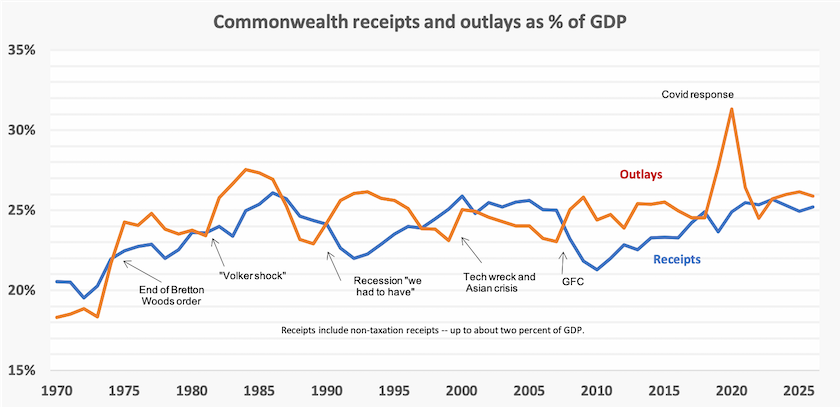

But the future will see stresses on both expenditure and revenue. On the revenue side, the trajectory of returns from the GST and fuel excise is downwards. And on the expenditure side government services are going to demand more resources, even if we simply try to maintain the current level of services. That’s because, compared with the private sector, there are fewer opportunities for capital-labour substitution in government services, which include intrinsically labour-intensive activities such as teaching, caring and policing.

This trend, requiring public expenditure to rise faster than private expenditure, was identified by economist William Baumol in the 1960s. Also, unless we can reverse the established trend towards widening inequality, there will be a growing demand for government social security transfers. If we have to increase taxes, rather than simply shifting their impact on different groups, a Pareto solution in the short run is not available.

The Coalition’s policy on tax, which seems to be engraved in stone as talking points for ministers, is that the Liberal Party “has always been the party of lower taxes, and that’s going to continue”. In other words it “has always been the party of a class-divided education system, expensive health care, privatized government services, miserable social security benefits, and an economy hampered by inadequate public investment, and that’s going to continue”, although they don’t feel inclined to express it that way. In office they have often set as a goal a cap on Commonwealth taxes at 23.9 percent of GDP, a figure untraceable to any source or objective criterion, in origin similar to Douglas Adams’ 42 in The hitchhiker’s guide to the galaxy.

A half century of government receipts and outlays is shown in the graph below. It’s a story, over the last 16 years since the shock of the GFC, of Commonwealth taxes trying to catch up with outlays.

At some time we will have to deal not only with shifting around the mix of taxes, but also the need to collect more public revenue.

1. Taxation data is from the OECD Revenue Statistics 2023 – Australia. The countries chosen for comparison are those 22 OECD members with per-capita GDP at purchasing power parity > $US40 000 in 2022, measured in 2015 US Dollars. With per-capita income of $US51 000, Australia is in the middle of that pack. ↩

2. America spends about 18 percent of its GDP on health care, of which about a third is covered by private health insurance.; This means private health insurance is the equivalent to a tax of 6 percent of GDP. ↩

3. Treasury estimates that superannuation contributions in Australia are about 7 percent of GDP. We should count this as an additional privatized tax, but to make a comparison with other countries we should also add the mandatory or near-mandatory contributions of their social security systems, and note that our contributions are heavily subsidized from public revenue. ↩

4. Data available from OECD Tax on personal income. ↩

The Tax Expenditures Statement – an insight into Treasury’s weird Weltanschauung

A document that should have attracted more attention is the Treasury’s Tax Expenditure and Insights Statement. Roughly speaking, it could be described as a statement about lurks in our tax system while the official definition of a tax expenditure is:

A tax expenditure arises where the tax treatment of a class of taxpayer or an activity differs from the standard tax treatment (tax benchmark) that would otherwise apply.

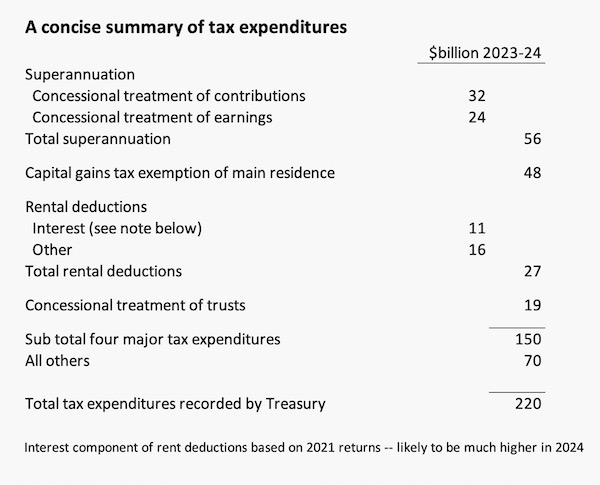

It lists 307 tax expenditures, which, if added up, come to a whopping $220 billion of tax forgone this year. To get an idea of the magnitude of tax expenditures, total tax collected this year is budgeted to be $650 billion. And the present round of tax cuts come at a cost to public revenue of $25 to $30 billion in the short term. But for reasons explained below, while there are many areas where more tax can be collected, there is no $220 billion sitting on the table.

A summary of tax expenditures, covering four main items, is shown in the table below.

Superannuation concessions dominate, relating to contributions to and earnings from superannuation funds. In its distributional analysis (which it applies to some major items), Treasury finds that these concessions are enjoyed disproportionately by higher-income earners. It also finds, unsurprisingly, that most benefits from earnings concessions are enjoyed by older people. Because many such beneficiaries would be high-wealth-low-income, the distributional inequity of tax-free superannuation for retirees with assets up to $3 million is understated in the Treasury analysis.

Treasury does no analysis of the distribution effects of exempting the main residence from capital gains tax. In the political arena it is emotionally called the “family home”, giving it a sacred status on the same level as Anzac Day. Simply applying capital gains tax to people’s houses, based on the CGT system distorted by the Howard government when it removed indexation from CGT, would have enormous problems. But there is every reason an inheritance tax, which would include houses, should be up for consideration.

Treasury’s analysis of rental deductions is strange. It classifies all rental tax deductions, including deductions for maintenance and rates, as “tax expenditures”. (In what way does allowing expenses incurred in earning an income differ from standard tax treatment?) Interest expenses are much harder to justify, because it is double-counting to allow both the depreciation of an asset and the cost of financing that asset as tax-deductible expenses. The $11 billion in that table is probably a significant understatement of the cost of allowing interest to be claimed as an expense because it’s based on interest rates prevailing in 2021. That $11 billion, and more, is the main cost to public revenue of “negative gearing”.

Treasury stresses that it is applying no normative standard to its classification or analysis: “The tax benchmark should not be interpreted as an indication of the way activities or taxpayers ought to be taxed”.

Yet in its choice of what to include it is making choices based on some value system. Notably it classifies the exemption of the Medicare Levy Surcharge – a surcharge on the Medicare levy for individuals with incomes above $93 000 who do not hold private insurance – as a “negative tax expenditure”. Yet the tax they pay is a contribution to public revenue. The normative assumption underpinning Treasury’s framing is that people should hold private insurance: the surcharge is akin to a fine. But by what standards should the well-off be encouraged to hold private insurance, jumping the queue for scarce resources, and contributing to higher health care costs? By most conventions of economics the Medicare Levy Surcharge is a generous and undeserved subsidy to the finance sector – the private health insurers.

Also, Treasury goes on to undertake a distributional analysis “on aspects of the personal tax system”. It has chosen “deductions, trust distributions and franking credits”. Why these?

Its treatment of trusts is strange. The $19 billion in the table relates only to capital gains tax concessions, which it treats as a “tax expenditure”. But it does not look at the cost of the other aspects of trusts, by which income from small businesses can be distributed to family members on low or zero tax rates. It notes this feature, but does not calculate its cost to revenue. This omission is unfortunate, because it puts no pressure on Labor to abide by its often-made promise, when in opposition, to crack down on trusts.

Treasury has chosen to report on individuals’ work-related expenses and dividend imputation credits as tax expenditures, even though the first is simply the same as expenses claimed in incorporated businesses, and the second is an integral part of our company tax system, that Treasury concedes is designed to “prevent the double taxation of company profits distributed to resident shareholders”. We might recall that Labor in 2019 went to the election proposing to disallow imputation credits for most superannuants: it was a poorly conceived idea because it would have contributed to housing inflation and have been easily avoided by the wealthy. Applying normal income tax scales to superannuation earnings, as the Treasury analysis shows in its treatment of superannuation earnings, would raise more revenue and would be less distortionary than disallowing imputation credits.

Treasury’s analysis is probably flawless in its arithmetic, but its assumptions about what is and isn’t a tax expenditure and its choice of what to analyse for distributional benefits reveals weird thinking. An inference one can draw from this document is that Treasury sees the taxpaying community in two categories: there are corporations who abide by the rules, but individuals are untrustworthy wretches who will use every rort to reduce their tax – work-related expenses, incurring expenses in letting property, imputation credits. If only the plebs would be well-behaved workers and let the PAYG system, administered by diligent employers using MYOB, manage their tax affairs, we would have a better tax system.

An even broader inference is that Treasury’s sole concern is with collection of revenue, with little regard for the economic consequences of the way revenue is collected, just so long as broad fiscal targets are met, consistent with macroeconomic fiscal and monetary settings. Perhaps this is a consequence of Prime Minister Fraser’s 1976 decision to split Finance from Treasury. It certainly means that, in spite of Treasury having some of Australis’s brightest economists in its ranks, broad taxation reform is too important an issue to be left to Treasury.

More on the tax cuts – Morrison’s cuts and Albo’s tweaks come with the same fiscal cost

Most public commentary on the government’s tax cuts is positive. William Bowe’s Poll Bludger reports on the Newspoll finding that 62 percent of respondents believe that the government has done the right thing while 29 percent oppose the government’s changes, and only 18 percent of respondents believe they will be personally worse off as a result of the changes.

Most of this comment, however, is about whether the government’s amendments improve on the Morrison stage 3 cuts. Apart from a few surviving believers in Reagan’s “supply side” economics, there are few who could mount a case arguing that the Morrison cuts are better public policy than the government’s amendments.

But the Grattan Institute takes one step back, pointing out that the Morrison cuts and the government amendments are fiscally similar, in that they both cost the budget more than $20 billion a year, or about one percent of GDP. This is in an article by Brendan Coates and Joey Maloney: The budget is the biggest loser from these tax cuts.

The government’s tax plan will make it harder for this and future governments to meet community demands for more spending in areas such as healthcare, aged care, disability care, and defence.

That draws attention to the whole frame of the political argument, which so far is about “how much better will I be with a $X tax cut”. There is no magic pudding of public revenue, however. Even without going into the wider question of collective versus individual responsibility, we should be asking “what public services will I forgo if my taxes are cut by $X”. This is particularly important if the issue is not simply about redistributing a previously committed tax cut – the present situation – but about introducing a new round of cuts as foreshadowed by the Liberal Party in its recent statements.

Another piece of analysis from a direction not covered by the mainstream media is a regional analysis of the cuts by the ABC Digital Story Innovation Team. Their post How the revised tax cuts affect people like you is a rich infographic about the distribution of benefits by gender, age and occupation. It confirms that the benefits are concentrated among younger workers. Its regional analysis by postcode shows that in rural regions taxpayers will do much better from the amended cuts than they would have under the Morrison legislation, and that they will generally do better than urban taxpayers. In fact in vast areas of rural Australia there are notaxpayers with incomes above $180 000. It is a political puzzle that the National Party meekly went along with the Morrison cuts.