Politics

Our Constitution – if you don’t know, you’d better find out, because we need to re-engage with it

It seems that every American has some awareness of their Constitution and how it affects their life, particularly about the right to bear arms (Second Amendment) and the rights of those accused of a crime (Fifth Amendment), even if they don’t know much about its rules of governance.

In Australia, however, it is possible for a right-wing populist to run a successful campaign “if you don’t know vote no”, as if Australians should occupy their minds with things other than our Constitution because it is all well and settled.

But the provisions of our Constitution and the way they are interpreted (or ignored), have a bearing on our lives – on our rights as citizens, on who governs our nation, and on how powers are split between the Commonwealth and states. All need revision.

Our rights as Australian citizens

The US Constitution has 18 instances of the word “citizen”; ours has only 2, and they are in relation to foreign citizens. In fact until 1949 there was no such thing as an Australian citizen. The US Constitution starts with a lofty preamble about “a more perfect Union”, to “establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty”. The First Amendment specifies freedom of speech, freedom of the press, and the right of people to assemble peacefully.

Ours by contrast, lacks a preamble, and confines itself largely to administrative matters. Apart from the right to exercise any religion (Section 116), and some specific rights about acquisition of property), there is no mention of rights or general principles.[1]

Bronwyn Kelly of Australian Community Futures Planning notes that our Constitution also lacks any mention of democracy: all it covers is a set of rules on voting, but as she stresses “elections do not a democracy make”.

In a four-part essay Saving Australian democracy and sovereignty by building a new Constitution Kelly puts the case for a new constitution. She states:

Australia’s Constitution leaves electors and the elected alike with no understanding of the preferred character, values and destination of the nation – what I have called here “the national project” or “the purpose of the nation”. As such, it leaves political parties with no legitimate means of describing to Australians how a term in office by one or another of them will serve the real interests of the public and the nation now and for the longer term. By default, the Constitution forces political parties to develop policy platforms in a vacuum.

She calls for a process of community engagement to develop a constitution that specifies “terms of trust” we might issue to those we elect. This goes beyond the notion of a social contract. Rather it would “specify our values, human rights and particularly our right to a voice in our own governance”. She goes on to state that:

… in a multicultural nation that means we need to find a way to accept the necessary coexistence of the necessarily different rights of distinct individuals and groups, understanding that human rights cannot be mutually exclusive – the rights of some cannot cancel out the essential rights of others.

With such an understanding a proposal such as the First Nations Voice would have more support, because there would be no possibility for its opponents to argue that it places the rights of some citizens over the rights of others, as the “No” campaigners deceitfully asserted.

Our fragile governance – who appoints our prime ministers?

The historian and constitutional expert Jenny Hocking dedicated a large part of her life, and took huge financial risks, in an endeavour to uncover what are known as “The Palace Letters” – communications between Governor General John Kerr and senior advisors to the Queen of England around the time of the 1975 dismissal of the Whitlam government.

Her endeavour is covered an a one-hour ABC TV program The search for the Palace Letters.

On a dramatic level it’s about a determined and dedicated historian struggling to get public officials to release 50-year old documents covering the most controversial governance event in our history. A government enjoying a majority in the House of Representatives was dismissed by an unelected appointed official, but the processes around that act, while being in the Australian archives and in the archives of a foreign country’s monarch, were kept secret from the Australian people.

It’s about our bizarre constitutional arrangements, which allow the reserve powers of a foreign monarch to be used to sack an elected Australian government. The correspondence Hocking has brought to our attention blows away the myth that the king or queen of England is disinterested in and detached from our political arrangements.

It’s about the way we appoint our de-facto head of state, essentially as a decision by the prime minister. Kerr’s behaviour around the dismissal is that of a disturbed person with little understanding or respect for democratic conventions. Malcolm Turnbull describes him as one who behaved “like a colonial governor”. There is nothing in our constitutional arrangements preventing the appointment of another Kerr.

As has often been stressed in these roundups, Australia is in a slow and probably irreversible transition, from a two-party “Westminster” parliament to a multi-party arrangement. We have already had one federal election, in 2010, in which the government did not have a majority in the House of Representatives. If an election were held today, it is highly likely that neither Labor nor the Coalition would have a House of Representatives majority. In such a situation it is probable that some arrangements to secure confidence could be negotiated as in 2010, but it is possible that the governor-general would have to make a decision to appoint a government or to call another election. Anyone who has been following the politics of Malaysia, Brazil, the Netherlands and Poland will understand that the head of state sometimes has to make a political decision. Do we accept that such a decision can be the responsibility of an appointed official and a foreign monarch?

This is why we need to engage in a serious discussion about our constitutional arrangements, leading to a referendum to determine the way our head of state is appointed and to clarify his or her powers. Although some in the Coalition have an attachment to Britain and its monarchy, there should be no doubt about the need for our head of state to be an Australian, with no specific relationship with Britain or any other foreign country.

The January 30 Essential poll shows that support for “Australia becoming a republic with an Australian head of state” has hovered around 40 to 45 percent for the past 7 years. Older Australians are less inclined to support a republic than younger people, but the age differences are not strong. There are more significant differences according to voting intention: Coalition voters are far less supportive of the idea than voters for other parties. And there is a significant gender difference: women are more inclined to hang on to our present system than men. Maybe the Women’s Weekly has something to answer for in blocking our progress towards shaking off the anachronism of having a foreign head of state.

Maybe the term “republic” has some bearing on responses, because it brings to mind America’s dysfunction model, and the stereotype of a despotic authoritarian dictatorship in a country calling itself a “republic”. Whether or not the head of state is called a “president”, a “governor general”, or a “boss cocky” is a minor matter, as is the official name of the country as a “republic”, “federation” or “commonwealth”. What counts is the way the appointment is made.

A separate poll by Demos shows that there is reasonably strong support for holding a referendum on a republic – 47 percent in favour, 38 percent opposed. It finds the same age and partisan differences as the Essential poll.

On partisan differences it’s notable that of our last four Coalition prime ministers three were royalists, who not only expressed their loyalty to the British monarch, but who also tended to favour the UK in matters such as defence purchasing and trade. Their official travel was almost as UK-centred as Barry McKenzie’s. The Coalition’s role in thwarting the republican movement may be something more than their usual practice of wedge politics: it may actually be based on a particular affection for the UK, a country whose national interests clearly separated from Australia’s interests in February 1942.

When models of appointment of the head of state are surveyed, there is no model that commands majority support. “Direct election with open nomination” has strongest support, with declining support for other models. As was the case in 1999, if the government were to put a referendum to the people, necessarily including details of the method of appointment, it would almost certainly fail, particularly while Dutton and his wreckers hold the reins of the Liberal Party.

But that doesn’t mean the government should abandon its aspirations for constitutional reform. We need a national discussion on our constitutional arrangements, starting with an information campaign: “if you don’t know here’s how you can find out”. Then a plebiscite along the style of the same-sex marriage plebiscite: “should we have an Australian head of state?”. And finally a referendum on the constitutional provisions. That will all take time – time enough for the remaining staunch monarchists to depart this life and for the Liberal Party to reform or be replaced by a serious centre-right party ready to argue for Australian interests.

Commuter car parks, gun clubs and change rooms – all unconstitutional

The Coalition government in office from 2013 to 2022 was adept at pork-barrelling, as many ANAO reports revealed.

Although sometimes mentioned in these reports there has been less attention paid to the fact that funding for most of these projects was probably unconstitutional.

Federations require a statement of the respective roles of federal and state governments. Our Constitution specifies the Commonwealth’s role in Section 51, which lists 39 powers for the Commonwealth, the rest falling to the states. It includes obvious powers such as immigration, foreign affairs, weights and measures. But nowhere is there any mention of commuter car parks, gun clubs, or change rooms.

Writing in the Saturday Paper – Unlawful federal government spending on local projects must stop (paywalled) – constitutional expert Anne Twomey points out that most of the Commonwealth government’s involvement in projects bypassing state governments, apart from those covered by Section 51, are unconstitutional.

Although in opposition Labor made an issue of the Coalition’s pork barrelling, with a little renaming and a few tweaks to improve accountability, it has kept the Coalition’s regional grants programs. The government’s excuses for retaining these programs are weak, essentially boiling down to “if they did it, we can do it”.

Governments can go on making these grants because there is unlikely to be anyone willing to stand up and wave the Constitution to challenge a new stadium or cycle track. No one wants to be thought of as a party pooper.

As Twomey remarks, if the Commonwealth wants to encourage sports participation or to make life easier for commuters to travel, it can do so through grants to state governments. In doing so it would save a lot of administrative expense and lot of political effort, and states generally do a better job at local projects than the Commonwealth. But the capacity to hand out grants is one of the perks of office: where would a local member be without a couple of projects to announce as an election nears?

In any event, research in America, partially replicated in Australia, shows that pork-barrelling doesn’t help improve a government’s vote. In a Conversation contribution Ian McAllister points to research showing that it’s not a big vote winner. Earlier USA research suggests that it may help a local member achieve re-endorsement in his or her party, but that’s unlikely to be the case here because we don’t use the American primary system.

1. In 1999 at the same time as the republic referendum, there was a referendum on the inclusion of a preamble. It secured only 39 percent support – lower than the republic which had 45 percent support. ↩

Transparency International’s report card – Australia has slackened off

Australia’s score on Transparency International’s corruption perception index improved in 2022 with the departure of the Morrison government, but the 2023 index shows no further improvement. We are still at position 14, with a score of 75/100. That is much lower than the score of top-performing countries, including the Nordic countries and New Zealand whose scores are between 80 and 90.

The short report on Australia – Australia’s corruption fight is at the crossroads – notes that we are “woefully behind where we were (85/100) just a decade ago” (before we elected the Abbott government).

The report on Australia mentions some issues that are a legacy of the Morrison government – the PWC scandal, Robodebt and allegations against Stuart Robert. But it also notes that the government seems to have stalled on promised reforms to political donations, whistleblower protection, and money laundering.

Radio National has a 9-minute interview with AJ Brown, professor of public policy and law at Griffith University and board member of Transparency International Australia, explaining Australia’s performance. He covers the same ground as the report, while adding the point that while our anti-corruption legislation has been a welcome step forward, it falls short on transparency. We might recall that even though the government had enough support to pass legislation for public hearings in corruption investigations, it yielded to demands by the Coalition to drop this requirement.

January 26 – fifty shades of meaning

The savagely divisive and deceitful campaign against the Voice has left its mark on the way we see meaning on January 26. Some want to ignore the day, because any reminder of that campaign is just too painful. Some see it as a day of silent protest and insist on going to work rather than taking a holiday. Some see it as a day to re-invigorate a campaign for truth-telling, treaty and voice. These perspectives are described in an ABC post The Voice referendum result has fired up some Indigenous leaders on Australia Day, but others need time to reflect by Bindi Bryce, Shauna Foley and Jenaya Gibbs-Muir.

The idea that January 26 should retain its once-agreed meaning as a day of celebrating national pride has been losing support for many years, as confirmed in research conducted by David Lowe, Andrew Singleton and Joanna Cruickshank from Deakin University and published in The Conversation: Support for Australia Day celebration on January 26 drops: new research. There is a significant difference among age groups: older people want to retain January 26 in its traditional form, but even within age groups attitudes are changing, generally shifting to the view that out of respect for indigenous Australians we should celebrate our national achievements on some other day.

The January 30 Essential poll has two questions on January 26. One is about people’s intention for the day: “just another holiday” beats all others. Another is about whether we should have a separate national day. On this question there is no dominant view. Could that be because no salient date comes to mind – Phar Lap’s death, Cathy Freeman’s 2000 gold medal, Scott Morrison’s resignation from Parliament?

Another survey, posted in The Conversation by academics from three universities, reports on attitudes to January 26 (among non-indigenous Australians), and how those attitudes relate to their vote in the Voice referendum: The more you know: people with better understanding of Australia’s colonial history more likely to support moving Australia Day. They found that 69 percent of No voters opposed changing the date of Australia Day, compared with only 22 percent of Yes voters. Similar, but not quite so strong, correlations were found on attitudes to other aspects of the Uluru Statement (truth and treaty), flying the ATSI flags, and acknowledgement of Country at official events

Their research suggests that “community ignorance and apathy towards Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander issues may lie at the core of the No vote. This could also drive reluctance to change the date of Australia Day.”

The organized demonstrations in our capital cities had a good turnout, but compared with previous years’ demonstrations, which were clearly focussed on invasion and dispossession experienced by indigenous Australians, this year’s demonstration included solidarity with the people of Palestine (note the Palestine flags in the photograph), and solidarity with some other issues about colonization, such as Indonesia’s occupation of West Papua.

It’s as if those who campaigned for a No vote on the Voice, by spreading fake news, lies, bullshit and misinformation, have managed to make the issues around the original owners of this land so confusing that people have resorted to a general protest against all wrongs associated with colonialism. It’s an unsatisfactory way of dealing with Australia’s particular situation, but it probably aligns with what Dutton and other No campaigners were after.

As for Dutton’s attempt to cancel Woolworths, Amanda Spry and Daniel Rayne of RMIT University deal with it in a Conversation contribution What’s behind Woolworths, Aldi and Kmart distancing themselves from Australia Day?. These firms were simply making calculated commercial decisions because people’s proclivity to wave flags on 26 January has declined. It wasn’t about corporate political activism, but that’s how Dutton tried to frame it in his war against woke.

There is something hypocritical about Dutton, who believes that Australians owe allegiance to a foreign king, urging us to celebrate our nation’s achievements. Perhaps Coles, Woolworths and other retailers would find a rise in demand for national symbols if we had our own flag, rather than one which includes the flag of a foreign country, and which is increasingly the banner chosen by “sovereign citizens” and Nazis.

What do we expect of government?

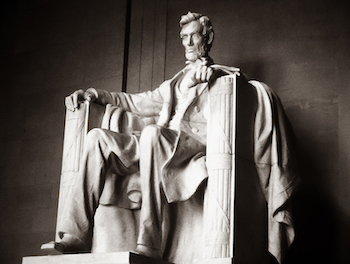

Lincoln said “The legitimate object of government, is to do for a community of people, whatever they need to have done, but can not do, at all, or can not, so well do, for themselves – in their separate, and individual capacities.”

That covers most theories of government, apart from communism at one extreme, which collectivises all economic activities, and the extreme forms of neoliberalism, which sees government as an unproductive overhead: the smaller the better.

In a major project involving surveys over the last eight years, the Centre for Policy Development has been asking Australians what they see as the purpose and functions of government, and has published results in a major report, its 2024 Purpose of government pulse.

The most significant finding, perhaps, is that when asked what people see as the main purpose of democracy, from a set of six options, the leading choice was “ensuring that all people are treated fairly and equally, including the most vulnerable”. The option “electing representatives from your community to make decisions on your behalf”, which may be seen as a minimalist definition used by elected dictators, came in at third place. In another part of the survey respondents, particularly younger people, expressed strong faith in the capacity of Parliament to tackle major challenges. This contrasts with the view, expressed by the present opposition leader, that Parliament is an annoying hindrance to executive government.

When asked “what do you think is the primary purpose of government” the leading response was “ensure a decent standard of living”. Unsurprisingly this response has risen to prominence over the last ten years, the period when real wages have been falling for most Australians. We might imagine a more libertarian people choosing equality of opportunity, or provision of infrastructure, both of which were options. Also on offer was “maintain public safety and the rule of law” – the law’n’order option – but this scored a low ranking.

Most people (four in five) want the wellbeing of the population to be the primary guide to public decisions. This may appear to be so obvious that it’s not worth asking, but there are times when politicians and commentators get carried away with objectives such as maximizing economic growth, forgetting that the purpose of any policy is people’s wellbeing.

The Centre’s surveys have covered many grounds, some of which have strong messages for policymakers. Overwhelmingly people want government to deliver services rather than to contract them out: this has implications for employment services, NDIS and human services generally. People want governments to take a long-term approach to public policy: that’s often revealed in surveys, but when there is political polarization an opposition party cannot resist the temptation to make political capital out of short-term problems while governments direct their energies to long-term structural reform, as is happening around issues such as electricity prices in the short term.

The report has several sections as stand-alone contributions from public policy experts commenting on the survey findings, and the main findings are outlined in a 7-minute Radio National interview with Andrew Hudson of the Centre for Policy Development: How satisfied are Australians with democracy?.

How is our government travelling?

Listening to journalists, not only those from the Murdoch stable, the impression one gets is that support for the Albanese government has collapsed, and that if an election were held today Dutton would cruise to victory.

The numbers tell a more complex story.

At the 2022 election Labor won 33 percent of the primary vote, the Coalition 36 percent, and the Greens 12 percent. The two-party result after preferences (TPP) was 52:48 for Labor. (ABC Party Totals). In terms of representation the result was a severe defeat for the Coalition (lost 18 seats) and a small gain for Labor (gained 8 seats resulting in a one-seat majority).

After the election, presumably when people found that the Albanese government wasn’t as scary as Morrison had portrayed it, and that the Coalition government had been approaching Nigerian levels of corruption, support for Labor rose to around 38 percent, while support for the Coalition fell to around 32 percent. The TPP polling numbers were around 57:43 – a lead which would leave the Coalition as a fringe party with a few seats in non-metropolitan Queensland.

That lead has fallen away, as shown on William Bowe’s BludgerTrack.

The most recent polling suggests that support for the main parties is back to within one percent of where it was at the election.[2] Perhaps the Greens have picked up a little support at the expense of Labor. The TPP figures show that Labor is still in positive territory, but by a margin more like the 52:48 at the last election. Care must be taken in interpreting TPP figures, because they carry the margins of errors of party estimates, and there are many assumptions in their generation.

At this stage any effects of the changed tax rates would hardly be showing in voting intention polls. Pundits are prone to overstate the effects of both a broken promise and the expected tax cuts.

In the Saturday Paper just before Christmas John Hewson wrote about the Coalition, stating “Negativity and denial are not election-winning policies or strategies. Nor is continuing to drag the Coalition further and further to the right of the political spectrum”. The article is paywalled, but its headline This Coalition is unelectablesummarises his view in four words. He doesn’t write “The Coalition is unelectable”: rather he is writing about this Coalition, the one headed by Peter Dutton, with Sussan Ley, Dan Tehan and Angus Taylor in the shadow cabinet.

The Albanese government has certainly lost its gloss, but it is hard to imagine any voter switching to the Coalition because Labor has spent too little on housing, education or health care, because Labor has been too soft on fossil fuel companies, or because Labor has been too tough on Palestinians. Journalists need to break from their assumption that what’s bad for Labor is good for the Coalition: Australia’s political landscape has been slowly moving away from the two-party system for 80 years.

The Dunkley by-election, in four weeks’ time, will reveal how Labor is travelling in an outer suburb with a profile that’s close to the national average on most dimensions. Labor holds it with a 56.3:43.7 TPP outcome, and the trend so far this century has been for the seat to swing from Liberal to Labor. William Bowe has an informative election guide on his website.

Then there is to be a by-election in Cook, also an outer suburb, which Morrison won in 2022 on a 62.4:37.6 TPP outcome. It is the sort of urban territory the Liberal Party can still hold – more prosperous than working class suburbs, but not as prosperous or as well-educated as suburbs where independents and Greens have done well.

2. The average of the most recent six polls (Essential, Newspoll, Morgan, Freshwater, Redbridge, You Gov), over December and January, shows that in comparison with the election Labor has lost 0.1 percent, the Coalition has gained 0.6 percent, and the Greens have gained 0.9 percent. Those figures imply a loss for independents and other parties, but opinion polls tend to understate support for independents. ↩