Other economics

The CPI – it’s a matter of interpretation

The December Quarter CPI rose by 0.6 percent for the quarter (that would be 2.4 percent if annualized), and 4.1 percent over the year to December. That low quarterly rise seems to have taken economists and financial markets by surprise, and to have eliminated expectations of an interest rate rise. Inflation fall “should kill off” any lingering rate rise risks is the headline on the ABC press release. A falling rathe of CPI inflation is confirmed in the Monthly CPI Indicator for December – a rough indicator covering the latest month but with less coverage and a higher margin of error than the quarterly indicator.

There is still enough in the data, however, for a zealous RBA Board to raise interest rates. They could note that the trimmed mean index (which rules out some volatile items) rose more strongly (0.8 percent) than the broad CPI, or that services inflation, a proxy for Australian labour costs, though falling, is still higher than goods inflation. Similarly “tradeable” inflation, an indicator reflecting world prices and exchange rates, has fallen faster than “non-tradeable” inflation, an indicator reflecting Australian costs.

But there is enough in other indicators, such as an unexpected fall in seasonally-adjusted retail sales in December, to suggest that heat is coming off the economy rather quickly. The Reserve Bank may have overshot – once again.

Does this mean all is well? That people can stop complaining about their supermarket bills? That the Murdoch media will stop blaming the Albanese government for floods, the wars in Ukraine and Israel, and for the Coalition’s past neglect of energy policy? Will non-partisan journalists stop talking about a “cost of living crisis” and start talking about an economy with serious structural problems in producing goods and services and in distributing the benefits of economic activity?

The good news in these figures is that inflation in food and clothing prices is particularly low. Falling gasoline prices have helped keep the CPI down. Electricity prices rose by 1.4 percent in the quarter and by 6.9 percent over the year. But for various government rebates they would have risen by 17.6 percent over the year. At the wholesale level, thanks to an expansion of renewables, electricity prices have fallen, and provided the privatized distribution and retail companies keep their fingers out of the till, retail prices could fall later in the year.

That all means the RBA Board should be able to sit back when they meet on Tuesday, or perhaps brush up on the mathematics of systems with high gain and slow response.

But we should remember what the CPI means. It may sound nitpicking to emphasize that it traces the prices of a representative “basket” of goods and services consumed by households, but it is important to understand its limitations. It is a pretty good indicator of inflation, but it is not a measure of inflation. Importantly, it is not necessarily a sound indicator of the cost of living, one reason being that the basket does not include interest payments. That’s because to count interest as well as the cost of the goods themselves, involves double counting. (I need a whiteboard, two hours, and a class of students motivated by an imminent exam to explain this.) In a Conversation article Why Australian workers’ true cost of living has climbed far faster than we’ve been told Peter Martin puts this in plain language, noting in relation to the CPI:

The index actually does a pretty good job of measuring changes in living costs at times when mortgage rates aren’t much changing. But at times when they are tumbling, it’ll overestimate living costs. And when mortgage rates are soaring – as they have been lately – it will way understate what’s happening to living costs.

That’s why, rather than talking about a cost of living crisis as if everyone is affected, we should be considering particularly the situations of households in particular difficulty, particularly those carrying significant debt – mainly mortgage debt but for poorer households debt on car loans and credit card debt can be burdensome. Another group doing it tough are renters: the rental component of the CPI has risen by 7.4 percent over the year, and for reasons to do with the ABS methodology, that figure probably understates the rise in new rent contracts.

The problems resulting in financial stress for many Australians result mainly from a decade of loose monetary policy, going back to the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, and from successive governments, Coalition and Labor, Commonwealth and state, having failed to invest in public housing and the general policy of Coalition governments having re-defined housing as a financial asset rather than as a basic need.

Childcare – affordability improved, but still prohibitively expensive for many

The ACCC has presented its report on childcare, as directed by the Treasurer in October 2022.

Its findings are unsurprising. The government reforms that took effect last July resulted in about a 10 percent improvement in affordability, but costs are now rising faster than inflation. Affordability and availability remain problematic: children in lower socio-economic advantaged regions are less likely to be enrolled in childcare than children in better-off regions, and there is a low supply of childcare in remote regions. The sector faces ongoing labor force shortages: labour costs account for about 69 percent of total costs.

The report reveals no evidence of excess profits: around a quarter of providers are making almost no profits or are reporting a loss.

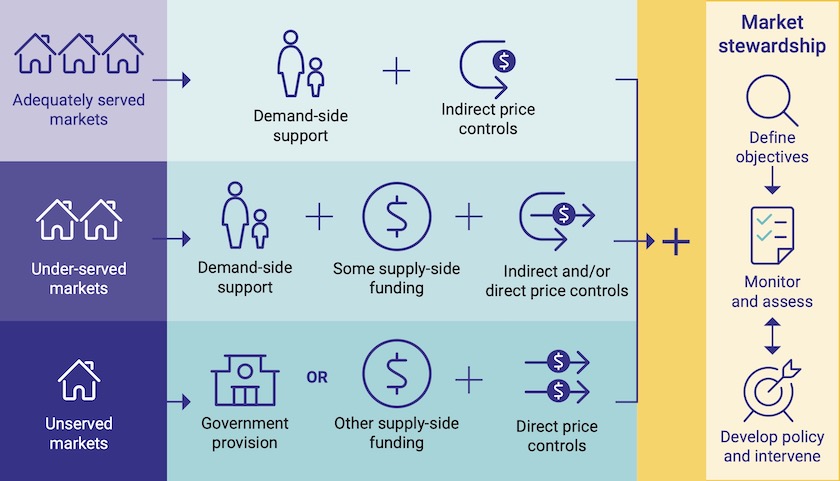

The ACCC finds that because there are different problems in different parts of the market, the government should respond with measures that address these specific problems, some on the demand side, others on the supply side, rather than a “one-size-fits-all” approach. It summarises its recommendations for intervention is a diagram, reproduced below.

While the ACCC does not find evidence that providers are making excess profits or exploiting consumers, it does report that rents paid by providers have risen faster than CPI inflation, and faster than rents paid by other businesses. It makes these observations without comment.

As in many human services, providers themselves are often in a weak position and can be exploited by those who provide inputs – in this case property owners. Childcare providers seem to be in a particularly weak market position because they need premises with specific design features: they are in a weaker position than businesses who can choose between market offerings of generic office space, for example.

Policymakers seem to take as a basic assumption that human service providers (and NGOs) will rent their premises, even when they require specific purpose designs. Measures that would help them own their premises would protect providers, and therefore the people they serve, from exploitation and the transaction costs of renting.

Similarly it is disappointing that the ACCC report makes no mention of insurance costs, which are probably high in businesses involving children. In health care, for example, liability cover is a generous cash cow for insurers: it would be surprising if child care does not experience the same exploitation.

Productivity – Ritalin, animal spirits, new public management and old academics

Ritalin and animal spirits

Australia isn’t the only country to have experienced a fall in productivity in recent times. It is happening in most “advanced” countries.

To restore productivity growth engineers call for more investment in big labour-saving machines, public policy wonks call for public investment in “soft” infrastructure such as education and in “hard” infrastructure such as railroads and telecommunications, and entrepreneurs call for the unleashing of “animal spirits” – whatever that means.

In an Australian Economic Review article with the tantalizing title Ritalin, animal spirits and the productivity puzzle, Tony Ward of the University of Melbourne provides some rigour to the idea of “animal spirits”. It is indeed something that can contribute to productivity, and there are ways of detecting it objectively, perhaps even subjecting it to some degree of ordinal measurement. Along the way Ward makes some thought-provoking observations about Ritalin, nutrition and economic growth.

He draws on Keynes’ idea of animal spirits. He writes:

In Keynes’ formulation, positive animal spirits give people “spontaneous optimism”— willingness to work harder, to take risks, to be innovative, and to invest more. Two factors influencing such optimism are the extent of social trust, and expectations of how fair, or corrupt institutions are.

We get the impression from business magazines that animal spirits are to be found only among executives and entrepreneurs, but Ward considers a much wider group:

What encourages Keynes’ “spontaneous optimism” to make investment decisions? These are not just by big business – they include individuals’ decisions to start new businesses, to invest in education, even just to increase economic participation. Key is surely confidence.

He acknowledges the importance of expected returns from effort and enterprise – the conventional conditions – “but more general are beliefs that the ‘system’ will work to reward initiative and hard work”. Economic systems corrupted by crony capitalism, rewards from rent-seeking, and dispensation of favours to mates, don’t work to reward initiative and hard work.

To confirm that proposition he looks at the relationship between countries’ scores on the Transparency International Corruption Perception Index and productivity growth. Although the determinants of productivity growth tend to move together, there is indeed an independent (negative) correlation between corruption perception and productivity.

New Public Management – the productivity killer

A lazy but common way to cost any activity – producing a bottle of beer, cleaning a square meter of a hotel room, marking a student assignment, or processing a visa application – is to look at the costs that can be unambiguously traced to that activity, such as direct labour and materials, and to add x percent to cover non-traceable costs or overheads. That x percent add-on generally includes the cost of people not directly associated with the product. There was a time when x was about 20 to 40 percent, but as private and public enterprises have become more loaded with hierarchies of managers, lawyers, human resource managers, public relations and marketing staff (ministerial support staff in the public sector), x has grown to well over 100 percent in most enterprises.

Such managerial bloat is one by-product of the cult of managerialism, discussed by four business and governance experts on the ABC’s Future Tense: Managerialism … and what it means for work. At its core is the idea of the generic manager, whose craft is management, and whose task is thinking, while those on the shop floor are engaged in doing. Managerialism is a neat philosophy, because it justifies the existence of business schools, provides a smooth path for MBA graduates to make it to the corner office, and justifies organizational caste systems and high executive salaries. It doesn’t matter if the so-ordained managers know little about the business or its technologies, just so long as the right performance metrics and KPIs are in place. What’s important is that the managers have the ability to exercise control.

In time in the private sector competition generally requires companies to trim their managerial layers, or to go broke, but as the commentators point out, managerialism tends to live on in the public sector, under the name “New Public Management”. Implementing New Public Management on public sector enterprises has provided easy cash flows for many Canberra consultants.

Those who are attracted to conspiracy theories might suggest that right-wing governments have inflicted New Public Management on the public service so as to confirm their dogma about the public sector being intrinsically inefficient, or to drive down the value of public enterprises so that they can be sold to the Coalition’s mates at bargain prices. But judging by the economic performance of Coalition governments in recent decades, a poor understanding of economics and accounting is a more compelling theory for their embrace of New Public Management than conspiracy.

Are old academics blocking innovation?

The hype of our time is that we’re living in an era of extraordinary innovation. The more mundane reality is that we’re experiencing the disruptions of inventions and innovations that occurred many years ago – for example the solar cell in 1883, the transistor in 1947.

The ABC’s Future Tense has a one-hour program, Research productivity and innovation is declining, in which four experts from diverse disciplines reflect on reasons why, although countries are still spending on research, and researchers are working hard, the productivity returns from research are diminishing. One reason they consider is that universities have become subject to the cult of managerialism, with an emphasis on performance metrics (usually the number of publications), rather than the quality of research. Another possibility is that older academics have become conditioned to work by churning out papers with little contribution to knowledge, blocking opportunities for younger people with ideas and a passion for discovery.

IMF’s report card on the Australian economy – we should be worried

The IMF has issued a regular progress report on the Australian economy. It’s generally positive on most aspects of the Australian economy and on the government’s economic management.

That’s why we should be worried, because the IMF is impressed by governments and central banks that practice fiscal and monetary austerity. It’s the sort of report card a Liberal government would love to have and can never attain, but for a nominally social democratic government it could be taken as a warning that our government is too risk-averse. The Reserve Bank would be encouraged by its statement that “Directors highlighted the potential need for further monetary tightening to achieve the targeted inflation range by 2025”.

It notes that there are “renewed increases in house prices”, and that there are “upside risks stemming from robust immigration” (an ambiguous statement).

We get a positive mention for our efforts to meet our climate mitigation targets, but we are urged to work harder to meet our 2050 targets.

Its forecasts for Australia’s economic growth are a little lower than those the government published in the Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook. It forecasts a modest pickup in private sector investment, but a sharp fall in public investment. Presumably the IMF sees a cut in the public sector as a positive, but in view of the state of our physical infrastructure this is not a promising forecast.