Tax cuts – sound economics, clumsy politics

“A war on aspiration” (Murdoch dailies), “The mother of all broken promises” (Angus Taylor), “Mark down the 24 th of July 2024 as the death of tax reform in this country” (Andrew McKellar ACCI), “Labor’s class warfare” (Sussan Ley), “Call an election” (Peter Dutton).

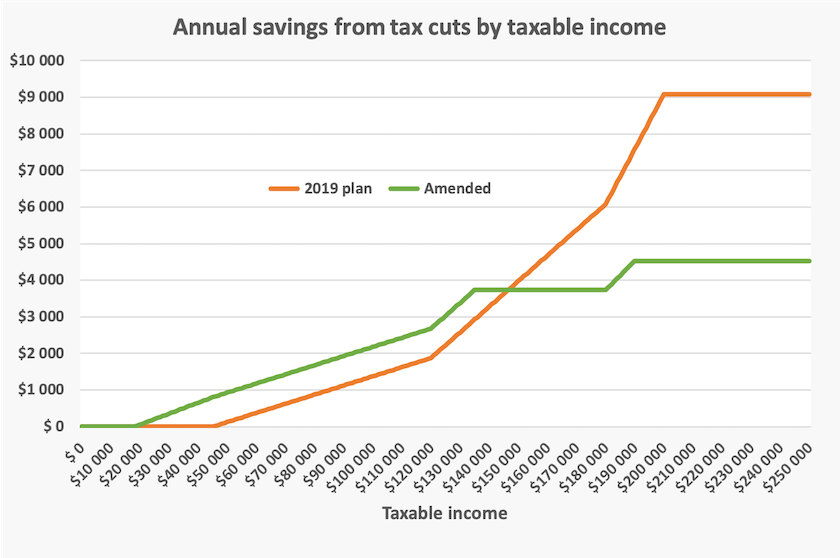

Dutton and his acolytes would be well advised to keep quiet on the tax cut, however. Every petulant outcry reminds the electorate that they’re defending a Coalition-initiated proposal to give an annual $9 000 tax cut to those with taxable incomes above $200 000 (about 3 percent of taxpayers), while giving nothing to those with incomes below $45 000 (about 28 percent of taxpayers).[1]

We’ll get on to the politics a little further on, but first the economics, because while there are plenty of “what’s in it for me” media articles, with their online calculators, there isn’t much on the economics of the overall change.

The government’s changes – meaningful changes from tweaks to rates and thresholds

The government’s changes to tax scales are in a short media statement by the Prime Minister. They depart from Morrison’s cuts legislated in 2019, by changing marginal tax rates and the incomes at which they cut in. Skip to the graph if you want to be spared the details, but to summarise, the government plans to:

- reduce the marginal tax rate from 19 percent to 16 percent for those on the first step with incomes from $18 200 to $45 000;

- retain the 2019 legislated reduction in the rate for the second step, which falls from 32.5 percent to 30.0 percent for incomes from $45 000 to $135 000, but restore the 37 percent step, now to cut in at $135 000. At present the 37 percent step comes in at $120 000, and the 2019 legislation abolished this step altogether;

- shift the final step, of 45 percent, to an income of $190 000 – halfway between the present threshold of $180 000 and the 2019 legislation of $200 000.

The graph below first shows the tax cuts by income, comparing the Coalition cuts (orange line) with the government’s amendments (green line). Note that the government’s cuts start at the (unchanged) tax-free threshold of $18 200, rather than at $45 000 as legislated in 2019. Note too that those on higher incomes still get higher dollar amounts of tax cut than those on lower incomes, a point stressed by Greens leader Adam Bandt in an ABC interview: Greens say tax cuts don't go far enough.

Everyone with a taxable income up to $148 000 (where the green and orange lines cross), about 91 percent of taxpayers, will do better under the government’s amendments than under the 2019 legislated changes – the package the Coalition is defending so far.

Economic consequences – positive by efficiency, equity and fiscal criteria

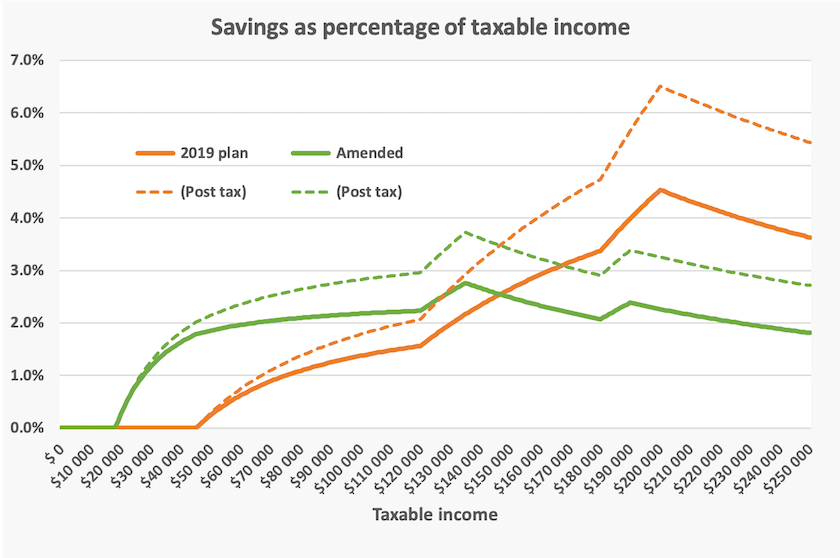

A second graph, on the saving as a percentage of income (pre- and post-tax), reveals the government’s economic thinking. The government’s changes give most taxpayers a tax reduction of around two to two-and-a-half percent (solid green line), or a boost to disposable income of about three percent (dotted green line). It is close to an across-the-board uniform percentage boost in disposable income, contrasting with the 2019 legislated changes, which are distinctly regressive.

A two to three percent increase in disposable income may not seem to be much, but it goes some way to compensating for real wage reductions over recent times. A Treasury document, Advice on amending tax cuts to deliver broader cost-of-living relief, reveals how the cost of living has risen over the year to September 2023 in different household types.[2] Households dependent on wage and salary income (“employee households”) have experienced a nine percent rise in their cost of living. Even if their income has risen in line with the CPI, around five percent, real incomes in these households have therefore fallen by about four percent. These tax cuts will therefore contribute materially towards restoring real income growth for workers.

That same analysis shows that households with other sources of income – mainly social security transfers – have experienced less cost of living stress. That is probably the main reason the government has not moved the $18 200 tax-free threshold upwards: its amendments are clearly directed at workers doing it tough. It’s starting to look like we have a Labor government.

Treasury’s analysis shows that the main beneficiaries will be workers in personal service occupations, including nurses, carers, and teachers. Unsurprisingly therefore women do particularly well from the changes.

These amendments should be fiscally neutral, and they should give the economy a boost in terms of higher workforce participation, because for low-paid occupations tax cuts encourage people to take up employment. (Tax cuts do not have the same motivation for the well-off.)

At the request of Adam Bandt the Parliamentary Budget Office has prepared a fiscal analysis of the originally legislated and planned tax cuts. Over the long term the amendments should put a little less fiscal stress on the budget than the legislated cuts, but the effect is so minor that it is reasonable to conclude, as the Treasury does, that they bear the same fiscal cost as the legislated cuts. The important point, overlooked by most journalists, is they still come at a cost to public revenue in excess of $20 billion a year, at a time when most government services are under financial stress. They show, unsurprisingly, that the benefits still go mostly to the well-off, but over time they become a little less unequal.

It is notable that 60 percent of taxpayers, including the vast majority of wage and salary earners, will have a marginal tax rate of 30 percent. For most people a promotion or a shift to better-paying employment does not mean crossing into a higher tax bracket.

There is the theoretical possibility that although the amendments are fiscally neutral they could be inflationary. This idea is based on the generally confirmed notion that the poor spend a boost to income, thus contributing to demand-pull inflation, while the rich save a boost to income. Treasury notes this phenomenon, and states that “even after factoring in this effect, the redesign will not add to inflationary pressures”.

The legislated cuts, introduced by the Coalition, are based on what earned the misnomer of “supply side economics” in the Reagan-Thatcher era. Give the rich an extra $9 000 a year (the Coalition’s plan) and they will spend it wisely, investing in new ventures which will give jobs to the plebs. Public policy should encourage the rich to contribute to society through their entrepreneurship, creativity, vision and wisdom – the qualities that made them rich in the first place.

The path to financial prosperity in Australia, however, is often through inheritances, profits from real estate and stock market speculation, less-than-competitive contracts for government works, the returns from protected monopolies and oligopolies, and government regulations rewarding rent-seekers. (The Howard government specifically changed tax laws to privilege financial speculation over long-term investment.) We shouldn’t imagine that those who have done well from the Coalition’s permissive economic policies would be transformed from conspicuous consumers into thrifty entrepreneurs by a $9 000 annual windfall. In fact, in some sectors such as mining, highly-paid workers are the most avid buyers of expensive 4WDs, boats, luxury housing and expensive holiday travel. Who can forget the image in the 2019 election campaign of a mining employee with a $200 000 salary abusing Shorten, because Labor’s policies of closing some tax concessions would drive the poor fellow into destitution?

We know from taxation data that only about half a million Australians have taxable incomes of $200 000 or more. That’s about 1 in 50 in the population, or 1 in 30 people in the workforce. Probably most of them sensibly understand that they are extremely fortunate to be the most prosperous people in one of the world’s most prosperous countries. But among their ranks are those who feel entitled, those who feel they have no obligation to contribute to the common wealth, and those who have no idea of how most Australians live. This is a cost of our social separation, exacerbated by the trend towards use of private schools and private health insurance, geographic segregation resulting from unaffordable housing, and the fading memory of shared experiences such as church attendance and national service. That’s all part of a bigger issue about inequality, which we’ll cover next week in a link from Martyn Goddard’s Policy Post.

Another story about the legislated cuts is that they should be considered as the final stage of a process of tax reform – hence the name “stage 3”. Those on low and middle incomes enjoyed their benefits in the first two stages; it is now the turn for the top end of town who have patiently waited in line. In a Conversationcontribution – The 2 main arguments against redesigning the Stage 3 tax cuts are wrong: here’s why – Simon Hamilton of ANU debunks that notion. The whole set of changes was aimed at deliberately making our income tax scales less progressive.

Spotless tax evasion?

Alan Kohler, writing in the New Daily – Good idea to keep the 37% tax rate, but the really rich are laughing at us – explains that the Coalition’s idea of scrapping the 37 percent step (now to be restored), was to make the tax scale a flat 30 percent from incomes of $45 000 to $200 000. That flattening not only aligned with the Coalition’s opposition to progressive taxation; it was also Treasury’s pragmatic acceptance that high-income taxpayers, particularly tradies and other small business people, were using trusts and corporate structures to evade the 37 percent step. Many people with small businesses are lax in their management. They fail to separate their personal from their business dealings, and they evade tax through counting personal outlays as business outlays. (Think of the spotless tradie’s HiLux never scratched by workers’ tools, or think of the way some plumbers, electricians and builders who provide services for a business and for the business’s owners, can be persuaded to disproportionately shift invoices to the business, thus allowing the owner to claim a tax deduction for personal expenditure.)

Labor in opposition has often vowed to clean up family trusts, but in government has yielded to the notion that an ABN is a licence to evade tax. That permissive approach to the apparently sacred “small business” sector is a serious breach of trust with the community, because most people are forced through PAYG arrangements to comply with taxation law, and people in business who assiduously abide by tax rules are undercut by competitors who flaunt the law. Labor’s backing away from its commitments on trusts is materially far more serious than breaking silly election promises about keeping the Stage 3 cuts, because in turning a blind eye to these methods of tax evasion (some would say “avoidance” because trusts are still technically legal), they are weakening the social contract embodied in taxation and damaging trust in the tax system.

The politics – poorly handled but the media should share the blame

If you have an hour to listen to two well-informed enthusiasts for tax reform, who have no connection to either of the two traditional parties, you can hear and watch Allegra Spender, Member for Wentworth, and Richard Denniss of the Australia Institute at the National Press Club, where they describe the politics and economics of tax reform. Their main message is that tweaking income tax rates is a good move but it isn’t real reform. There is also a transcript of Denniss’s points on the Australia Institute website, but it doesn’t capture his flair in explaining economic ideas.

If you have only a few minutes to spare you can watch Allegra Spender summarize her main points on the ABC’s 730 program. (9 minutes) Maybe Albanese’s decision to break a bad promise has opened up the possibility for broad tax reform to be on the political agenda.

The ABC’s Matthew Doran points out that the issue is politically difficult for both Labor and the Coalition: Anthony Albanese took a political gamble by breaking his Stage 3 tax cuts promise, but Peter Dutton's trap could backfire.

Pollster Kos Samaras, in an interview on the ABC’s Saturday Extra – Will the stage three tax cuts be the downfall of Albanese? – says that while the broken promise will soon be forgotten, failure to do anything about the cost of living for 90 percent of Australians while giving a windfall $9 000 a year to the most privileged would be politically disastrous for the government. In the interview Fran Kelly states that there has been “a dramatic slump in support for Labor over the last four months” (in fact Labor’s primary vote support is about where it was in the last election but her point is partially correct).[3] Kos Samaras says that whatever support Labor has lost can come back. (9 minutes)

Writing in the Saturday Paper – The stage three tax cuts are Albanese’s turning point (paywalled) – Chris Wallace sees it as a politically and economically positive move for Albanese:

Handing $21 billion a year to the highest-earning Australians and giving the rest none or, at best crumbs, during the cost-of-living crisis not anticipated at the time legislation was passed, doesn’t make sense even to many Coalition voters.

Perhaps the most revealing aspect of Wallace’s article is her revelation (already guessed by most political observers) that Treasurer Chalmers was urging his cabinet colleagues to amend the package, while Prime Minister Albanese was emphasizing the importance of keeping his promise. That is a break from political tradition and says something about Albanese, because treasurers usually work to restrain prime ministers’ ambitions.

The government’s changes seem to be going down well in the community. The January 30 Essential poll finds that only 22 percent of respondents believe the previously legislated changes should go ahead as previously planned. Independent Members of Parliament, Kate Chaney and Zoe Daniel, both representing prosperous electorates, report in an interview on ABC Breakfast (10 minutes) that the government’s changes have generally met with approval in their electorates, although they are critical of the way Albanese handled the issue.

They both call for indexation of tax brackets. That would result in the real rates of income tax remaining unchanged from year to year, attracting little political attention, while governments would have to account for real changes, such as adjusting marginal rates. (Governments can use bracket creep to their political advantage. They can leave tax brackets unchanged during their first and second years in office, and give a big tax cut, usually including de-facto indexation, before the following election.)

Chaney and Daniel both call for wider tax reform, including all aspects of taxation, as do Spender and Denniss in their Press Club address. Saul Eslake makes a case for broad reform in a 13-minute interview on ABC Tasmania. There is also an article in The Age by Natassia Chrysanthos – Teal MPs want tax reform on the agenda as they float support for new cuts – reporting on the views of Kate Chaney, Monique Ryan, Allegra Spender, Zoe Daniel, Sophie Scamps and Kylea Tink.

How journalists and the old political parties conspire to block broad tax reform

It is easy to look back on the 2022 election and say that Albanese should never have made that promise, or that he should have hedged it in some way – “… if there is no change in economic circumstances” perhaps. But given the Coalition’s capacity to use the slightest qualification in a statement as an opportunity to mount a scare campaign, and the outright lies about Labor’s taxation plans the Coalition used in the 2019 election, Albanese’s doggedness is understandable: he was playing by established but dysfunctional political conventions. As Allegra Spender says, the old political parties, Labor and the Coalition, go on wedging each other on tax issues, stymying the possibility of comprehensive reform

The problem lies in our political and media landscape, shaped by a tired political oligopoly, and by journalists who see politics in a frame that’s more akin to a football match than about ideas and political principles.

It’s unfortunate that political campaigns, which should be about competing policies, are reduced to hard and often immutable “position” statements. Military strategists and negotiation mediators warn that digging oneself into a hard “position” is disempowering, but our journalists insist on asking politicians “what is your position on X?”, and “can you rule out Y?”. Politicians have been conditioned to respond with positional statements, weakening their opportunity for policy adaptation.

When politicians dig into hard positions, as has now happened on negative gearing, journalists should force them to articulate the reason for their position with questions such as “what principles bring you to that view?”.

Partisan media use positional questioning as a political strategy, but journalists in unaligned media, including the ABC, also use it, possibly by force of habit, or as a way to add to a bank of statements to be used as gotchas in later interviews.

The public would be far better informed if journalists could use their interactions with politicians to get them to articulate their political principles. On the Voice, for example, such interviewing would have extracted from the Coalition a statement that their policy is one of cultural and political assimilation. On the tax cuts it would extract from the Coalition a defence of supply side economics as the principle behind the 2019 legislation, and would force the Coalition to explain why they believe that Australia should struggle with an underfunded and emaciated public sector, out of step with other prosperous countries. That would be more informative than asking Dutton what “position” he will take on the Parliamentary vote.

If a minor issue around changing income tax rates and thresholds has resulted in so much political pain, what hope is there for real tax reform, particularly when there are widening gaps between the taxes we collect and the financial resources we need to sustain government services?

1. Data on the distribution of taxpayers by taxable income is obtainable from the ATO’s site: Individuals detailed tables. In that page scroll down to the link to Table 16, from which you can download a detailed Excel file, showing the number of taxpayers, by gender, in each percentile of income. It covers Australia’s 11.7 million taxpayers. ↩

2. A detailed analysis, presumably drawing on the same primary sources, is in an RBA Bulletin article Developments in income and consumption across household groups by Benjamin Beckers, Ashwin Clarke, Amelia Gao, Madeleine James and Ryan Morgan.. ↩

3. What could have been an informative political discussion was interrupted by Kelly’s insistence on asserting Coalition propaganda, as if she was engaged in a partisan tussle between Kelly and Samaras, rather than an interview with a well-informed expert on political trends, to help the public understand public policy.. ↩