Policy challengess

Australia’s low-growth-low-productivity economy

Economists’ main concern in recent times has been about the way we get back to a normal pattern of stable growth as we emerge from the shock of the pandemic. But in fact in the years leading up to the pandemic – ever since the 2008 global financial crisis – our rate of economic and productivity growth has been unimpressive. We’re heading back to that pattern, not the high-growth pattern of the last half of the twentieth century.

On last weekend’s Saturday Extra Geraldine Doogue interviewed two economists, Nicki Hutley and Gerard Minack, about the structure of the Australian economy: Solutions and outlook for Australia’s rapidly slowing economy. (16 minutes)

They describe an economy that’s structurally weak. Our economic malaise is not because of a lack of opportunity, but it’s because of a lazy business culture that developed after the structural reforms of the 1980s. A high rate of immigration has provided a ready pool of labour, allowing firms to expand by taking on more workers rather than investing in capital equipment. Because firms have seen no need for capital deepening our labour productivity has fallen.

Also, important sectors of our economy – airlines, supermarkets – are subject to monopolization or a high degree of market concentration. The last 15 years or so have been good for corporate profits, but not for corporate investment.

On the same issue of market concentration ABC investigative reporter Adele Ferguson is interviewed about the proposed Senate inquiry into supermarket price gouging. (8 minutes). Notably the inquiry has been initiated by the Greens, not by the government.

We need to do something about school education but please don’t mention spending money

Almost everyone – parents, teachers, economists, education unions – are well aware that that the Gonski reforms, including the commitment to fund students and schools to a defined schooling resource standard, is a long way off achievement.

Progress is slow.

A year ago, in December 2022, Commonwealth and state education ministers set up a review to identify reforms needed to lift outcomes for all school students, particularly those at most risk of falling behind. This review, building on work by the Productivity Commission (the Commission’s report on the National School Reform Agreement released in January this year) has just been released: Improving outcomes for all: the report of the independent expert panel’s review to inform a better and fairer education system. This review provides a background, and a set of recommendations, to guide ministers as they work towards the next Education Funding and Reform Agreement, to be implemented by January 2025.

The full report runs to 248 pages. There is also a more digestible summary report on the Commonwealth Education Department’s website. On funding it couldn’t be clearer:

The Panel outlined that the first step to ensuring all students receive the supports they need must be to ensure that full funding to 100 per cent of the SRS [the Gonski Schooling Resource Standard] is achieved as soon as possible. This includes the SRS loadings which provide extra funding for priority equity cohorts and disadvantaged schools to help disadvantaged students achieve their full potential. The Panel’s Report highlighted that full and fair funding is a precondition to levelling the playing field for all students.

The full report explains the extent of the funding shortfall more starkly:

Although the Commonwealth and states and territories committed to the SRS funding model following the first Gonski Review, some schools are still not being funded to the minimum standard. This is most pronounced for government schools, with 98 per cent still being funded below the SRS on average.

The Conversation has an even more concise summary and critique by Glenn Savage and Jacob Brown of the University of Melbourne: A new report wants more funding and better support for Australian schools. But we need a proper plan for how to get there. There is nothing wrong with the panel’s general recommendations, but “many of its ideas and recommendations are not translated into tangible targets”, and it has little to say on the extent of the funding needed to bring government schools up to standard.

Education Minister Jason Clare’s media release has the right words on the panel’s report, but his statement is mainly about lifting the performance of students from poor backgrounds – an important consideration – rather than lifting the resourcing and performance for all students. In a 9-minute ABC radio interview he stresses the same point about addressing the need to attend to students from the poorest background and to lift our high school Year 12 retention rate, which has slipped in recent years. He reminds us that the economic case for such priorities is strong.

He avoids any hard figures, such as the states’ and education union’s demand that funding for government schools be lifted by 20 to 25 percent, but he does acknowledge the need to bring all schools to the Gonski SRS standards. Most government systems are on track to meet only 95 percent of that standard, and private schools won’t come down to that standard until 2029, thanks to Turnbull’s reforms. The Australian Education Union urges governments to get on with the job of improving funding: the need is urgent and critical.

The ABC’s Claudia Long and Evan Young have a summary of the review: More public school funding, student screening and teacher support among major review recommendations. The Guardian’s Caitlin Cassidy puts a particularly strong case for increased funding in her article: Australian public schools must be fully funded “as soon as possible”, independent review finds. Her concern is that the reform agreement, to be negotiated over next year, could “lock in another decade of underfunding”.

The national mood – gloomy and irrational

The latest Essential Report describes an Australia that seems to be heading into the same type of malaise that is infecting the US and some European countries – a general unhappiness and discontent directed at all institutions, and an expectation that things can only get worse.

Albanese’s favourability rating continues to fall, but whatever blip Dutton may have enjoyed from his behaviour over the Voice and the High Court’s detainee decision has dissipated.

The national mood (“would you say that Australia is heading in the right direction or is it off on the wrong track”), which was so positive 18 months ago, is now gloomy, across all age groups.

We think big business, governments, and unions have too much power, while individuals, workers, and small businesses have too little. Yet we want the government to use their power to reduce the prices of energy, grocery and houses. That suggests we see governments and unions as institutions pursuing their own interests, rather than as organizations for the collective good. This idea has been promulgated by the right for decades, and is hard to dislodge.

Trust in all institutions mentioned – scientific bodies, universities, health authorities, the justice system, the public service, state and federal parliaments – has been falling for three years, but has plummeted in the last three months.

We believe it’s been a bad year for everyone and every institution, except for “large companies and corporations”. The year just concluding was worse than we expected, and next year will be worse.

On all these questions there are predictable differences relating to voting intention and to age (older people are much gloomier than younger people, even though they are less affected by high interest rates).

To see this as a “cost-of-living” rage or as a specific move from Labor to the Coalition is far too simple. Apart from a slight uptick in support for the Greens, people’s primary votes are still where they were in last year’s election.

It is notable that this malaise has intensified in recent months, even as inflation has started to ease and as the Reserve Bank has become less zealous. It is also the same period in which Liberal Party shadow ministers Dutton, Ley, Tehan, Price and Taylor, have gone all out to sew discontent, fear and anxiety, with their voices amplified by the far-right media. This atmosphere has emboldened extremists, such as sovereign citizens, QAnon conspiracy theorists, and Nazis. Dutton may have unleashed a monster that cannot be controlled.

But is this malaise just to do with what’s happening here?

This has been the same period in which the war in Ukraine has turned to a 1914-18 style immobile slaughterhouse, in which two sides in Israel have unleashed terrible aggression against each other, and in which authoritarian strongmen – Wilders, Putin, Melei, Erdoğan, , Orbán – can claim, with some justification, that democracy is in retreat. At the same time the odds on Trump returning to the US presidency are firming.

Cost of living perceptions

Unsurprisingly, most Australians (72 per cent) say that their income grew more slowly than their cost of living over the past year. Only those with incomes above $200 000 say their income rose as fast or faster than the cost-of living.

That is the headline result of a survey conducted by The Australia Institute in early November.

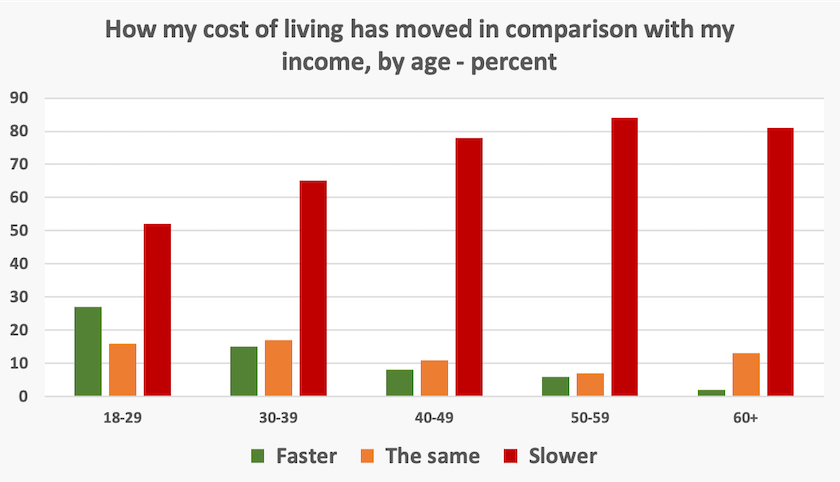

It is notable that older Australians are more inclined to report that their income has lagged the cost of living than younger Australians, as shown in the graph below, constructed from the TAI data.

This result is somewhat counterintuitive. Younger people are more likely to be renting or have high mortgages than older people. Retirees are among the few who may benefit from higher interest rates and indexed pensions. Speculatively, it is possible that the results arise from younger people having comparatively more power in a tight labour market, being in age groups where promotions are easier to come by, or being more able to shift employment.

It is also notable that women are more likely than men to report that their income has risen more slowly than their cost of living. This is counter to ABS data on movements in income, linked in last week’s roundup, which showed women’s real incomes have been rising while men’s have been falling.

That’s not to suggest the TAI survey is wrong: its methodology is rigorous. But it is about perceptions: our perceptions of material well-being do not always align with physical reality. And maybe those perceptions are shaped by incessant media emphasis on the cost of living.

The survey has unsurprising results on partisan perceptions: while 40 percent of respondents believe Labor has a better approach to the cost living than the Coalition (33 percent), those aged over 60 believe that the Coalition has a better approach.