Other economics

The infrastructure review – a disappointment that still leaves room for pork barrelling

Still not much for long-distance rail

The Minister’s press release on infrastructure starts with an impressive headline: Nation-building infrastructure for a better Australia. It goes on to list six big projects “to be completed or substantially developed” over the next ten years.

That wording allows for a fair bit of latitude.

Then comes the news that some projects will not be funded.

We get some indication of how fiscal policies rather than need have shaped the government’s decisions, in a document Independent strategic review of the infrastructure investment program – executive summary. It doesn’t explain what makes the review “strategic” or what the adjective “executive” means, but it does assert that there are cost pressures on projects, and that “the ten-year pipeline of projects cannot be delivered within the $120 billion allocation, even with current contributions from jurisdictions.”

Where did that figure $120 billion come from?

We don’t really know. We might believe that it relates to forecasts of immigration and population growth, and assumptions about future demands on the construction workforce elsewhere in the economy, in mining projects for example, with estimates subject to sensitivity analysis. But there is no such analysis. There’s simply the assertion that the government has constrained itself to spending $120 billion over ten years.

There is evidence of Treasury’s dead hand all over this document.

Coincidentally perhaps, this document was released in the same week in which The Economist, in one of its leaders (probably paywalled), sharply criticized the UK Treasury’s obsession with short-term cash outlays:

Treasury has a culture of frugality that goes back to William Gladstone, a Victorian statesman who, as chancellor, was known for “saving the candle-ends”. The way the mighty finance department works is to focus narrowly on keeping control of near-term spending, even if that means squashing projects that make sense in the long term.

That’s in a country with a different history and a different culture, but our public institutions, including Treasury, have inherited many of the UK’s administrative practices. Treasury’s focus is on controlling spending, regardless of whether that is for capital or recurrent purposes. Government debt is just bad, whether it results from reckless spending or from investment in infrastructure for a growing population.

The Minister’s press release refers to the government’s Infrastructure policy statement, which provides a set of criteria which justify Commonwealth funding – essentially projects that serve national purposes that go beyond states’ specific interests, such as national highways and major airports. That suggests some reform in distribution of road grants, but the criteria are open enough to justify virtually any project. They read:

The Government considers nationally significant transport infrastructure projects to comprise projects which require a clear role for the Commonwealth, and include at least two of the following characteristics:

an Australian Government contribution of at least $250 million; and/or

• alignment with Government priorities as articulated in this document; and/or

• situated on or connected to the National Land Transport Network and/or other key freight routes, such as those identified in the National Freight and Supply Chain Strategy; and/or

• supporting other emerging or broader national priorities such as housing, defence, the development of critical mineral resources and Closing the Gap.

What road isn’t connected to the national network? Isn’t almost every local road supporting housing in some way?

It eventually connects to the Pacific Freeway

When we get to the list of projects that have been promoted, approved, shelved and cancelled there is some semblance of discipline. Gone are most of those Coalition’s commuter car parks. There is $1.6 billion for the M12 “Motorway” (freeway), linking Sydney’s road network to the new Nancy-Bird Walton Airport. But in the same New South Wales list there is $191 million for “fixing local roads”. In the South Australian list there is additional funding of $2.7 billion to complete Adelaide’s major north-south corridor, and there are allowances for a number of rural roads connecting South Australia’s roads to those in other states, but a bypass around Truro, a bottleneck on the Sydney-Adelaide highway, is ruled out.

The projects with a green light seem to be those that were most advanced, particularly if construction had commenced. That makes sense: there may be some projects that don’t achieve a positive benefit-cost ratio overall, but once they are advanced any work done has to be considered as a sunk cost. Such projects should be re-evaluated on the remaining cost to completion. In any event few things are as politically embarrassing to governments than partially-built and abandoned projects.

But why is the Commonwealth funding so many projects which cannot, by any stretch of imagination, have national significance? Why does not the Commonwealth simply hand over the funds to the states, if necessary as tied grants to be used for capital purposes or even specifically for transport projects, and let state governments decide their own priorities? That would not only be consistent with the Constitutional division of powers between the Commonwealth and the states (Section 51), but it would also remove the temptation for the government to get involved in local pork-barrelling.

Just three days after announcing the outcome of the infrastructure review, the Minister committed to a continuation and increased funding for the Roads to Recovery and the Black Spot programs.

Anyone familiar with the condition of our country roads knows that such funding is crucially needed. But why should the Commonwealth be involved in micromanagement of roads? Again, why not hand the $0.6 to $1.0 billion a year, promised by the Minister, to the states, perhaps with some minimum conditions such as requiring that X percent be spent on roads to remote aboriginal communities?

Before last year’s election Labor pledged to act on pork barrelling, but here we find the government continuing arrangements that will allow for close ministerial direction of discretionary grants. Research shows that most pork barrelling doesn’t work politically: as an example we can think of the damage the Coalition did to itself with sports rorts and commuter car parks.

The Centre for Public Integrity has called for an end to grant pork barrelling, drawing attention to a motion to Parliament by independent MP Helen Haines and Liberal MP Bridget Archer to reform the administration of discretionary grants. To quote from Helen Haines:

Such reforms would ensure grant guidelines and selection criteria are clear and publicly available, that public reporting on grants administration includes grants that are awarded contrary to advice given to the Minister, and a Parliamentary Joint Committee on Grants Administration would provide administrative oversight.

The Grattan Institute has a well-researched document Potholes and pitfalls: how to fix local roads, drawing attention to the shortfalls in funding for construction, rehabilitation and maintenance of local roads. It points out that 75 percent of our roads are managed by councils, but they are starved of funds. “Taxpayers would get better bang for their buck if the federal government spent an extra $1 billion on improving our local roads rather than on new megaprojects in the major cities” the authors assert. But the authors are not in favour of the Commonwealth getting involved in micromanaging local projects. Funds should flow through state governments and on to local governments.

Similarly, writing in The Conversation Jago Dodson of RMIT University – The government just killed 50 infrastructure projects – what matters is whether it will fund them on merit from now on – describes entrenched politicization of infrastructure funding. He advocates a process that would see the Commonwealth become much more hands-off in infrastructure.

It's as if, although the government has changed, the culture of discretionary grants hasn’t changed.

Will she or won’t she? Considering the next RBA decision on Tuesday 5 December

The financial community has been coming to believe that in view of the worldwide reduction in inflation and the damage inflicted by 13 interest rate rises in 18 months, the RBA has gone far enough, or too far, in raising interest rates.

But on Wednesday RBA Governor Michelle Bullock gave a speech A monetary policy fit for the future, which the media has interpreted as a signal that the Bank is far from done with interest rate rises.

The media has focussed on her reference to hairdressers and dentists, as indicators that a demand-supply imbalance in the service sector is driving inflation. Is the RBA so callous as to suggest that a greater incidence of tooth decay is an acceptable price for bringing down the CPI?

In fact while the RBA is indeed obsessed with services, the biggest price increases away from long-term trends, as revealed in her speech, are “rents”, “insurance and financial services”, and “dining out and takeaway”. They all have their own price drivers: rents are up because of a longstanding government failure to invest in housing, insurance is up because of climate change, and dining out is up because of what is probably a once-off adjustment in minimum wages.

In her speech Bullock repeated the truism that the Bank has only one blunt instrument. The more general point is that monetary policy rests on a crude model of an economy with just two entities “demand” and “supply”, with fungible resources. It’s a neat abstraction for teaching students Economics 1, and it probably describes the economy of slave labourers building pyramids 4500 years ago, but it’s not fit for purpose in a modern, complex economy with specialized resources and a wide range of demands.

In any event, we shouldn’t get too upset about the price of services rising. Our improved living standards over 200 years are due mainly to the technological progress making for cheaper goods, while the price of services – i.e. our wages – have risen.

Peter Martin, writing in The Conversation – Why further RBA interest rate hikes are less likely now than even 1 week ago – makes a point overlooked in Bullock’s speech. The Australian Dollar exchange rate is rising. Imports – gasoline, clothes, appliances – are therefore becoming more affordable. We may have to pay more for haircuts but are better off overall thanks to cheaper imported clothing, and we can be assured that hairdressers and their assistants are sharing in that increased prosperity.

That is, if the RBA isn’t spooked by the next ABS monthly CPI indicator, to be released next Wednesday 29 November.

Our age-divided economy – who’s struggling and who’s cruising

Wellbeing indicators

This week saw the release of the Australian Unity Wellbeing Index. Its first summary point looks alarming:

Australians' satisfaction with the economy has hit a record low, with satisfaction scores significantly lower than during the Global Financial Crisis. In turn, this has had an impact on our national wellbeing.

The impression one gains from the report is that while many of us find it a little harder to make ends meet than we did a year ago, we are more concerned about the nation’s economic situation than about our own material standards. That can even be considered a positive indicator of a sense of community cohesion.

The report notes that we remain generally satisfied with our standard of living, although there is a clear finding that our personal financial wellbeing is greater for those aged over 65 than it is for younger Australians.

Although the index is based on solid social research, the report states:

You don’t have to be a social researcher to figure out the reasons for this national malaise. Rapid-fire interest-rate rises and a housing shortage increased our mortgages and rents, which was compounded by surging grocery and energy costs. Yet the fallout is hitting certain groups particularly hard.

Financial data

Journalists harp on about a cost-of-living “crisis”, but there doesn’t seem to be any problem for Australians taking cruises, which have become far more popular in recent months.

The Commonwealth Bank uses data from its customers’ spending patterns to generate a Cost of Living Insights Report to give some indication of how we’re travelling. One finding in the November 2023 report is that people over 65 are spending more on travel and eating out, even in inflation-adjusted terms, than they were in the same period (July to September) last year. Spending on cruises is up 55 percent.

The main finding is that people on the whole are cutting back on spending, particularly discretionary spending. Even essential spending is not keeping up with inflation, which suggests some Australians are cutting back on things such as health care and food.

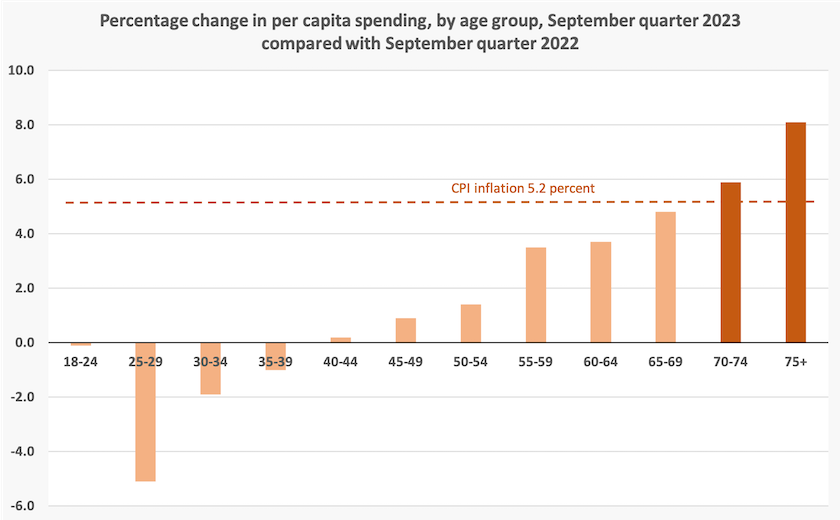

The hardest hit are those aged 25-29. It’s also notable that people living in metropolitan regions are cutting back more heavily than those in non-metropolitan regions, suggesting that capital city housing prices – rents and mortgage costs – are taking a regionally disproportionate toll.

Within “essential” categories the greatest rise in spending over the last 12 months has been in insurance, while in “discretionary” categories the greatest cutbacks have been in “household goods” and “general retail”.

The strongest message from the survey is that the cost-of-living burden is falling most heavily on younger people. The graph below, derived from the Commonwealth Bank data, shows how spending has changed by age group. Only those aged 70 or older have increased their spending in real terms.

As pointed out in last week’s roundup, this data does not reveal much about a cost-of-living “crisis”. Rather it is mainly about the uneven impact of monetary policy.

Now for the cruise

It is not only about the injustice of monetary policy: it is also about the ineffectiveness of monetary policy, because people have little capacity to cut back on “essential” expenditure. If monetary policy could be finely applied it would be directed at reducing older-people’s discretionary spending – perhaps a sumptuary tax on wine that comes in bottles rather than in casks.[1]

Or better, a fiscal approach. A starting point would be for the government to abolish or modify the Stage 3 tax cuts, and to tax the income from superannuation retirement funds in the same way as taxes are applied to those who actually earn their money through work and entrepreneurship.

Such an approach to fiscal policy is advocated by Emma Dawson, of Per Capita, in a 9-minute interview on ABC Breakfast: Interest rates fuelling generational inequality. We are confronted with an intergenerational crisis, which, if not resolved, will result in a class-divided society – those with inherited wealth and those who are perpetually struggling. This division is the result of 30 to 40 years of policies which have favoured a distribution of wealth to the already wealthy.

1. Perversely a sumptuary tax on champagne, BMWs and cruises would have little effect, because most expenditure on these items is on imports. ↩

An economic assessment of Jobkeeper

“Jobkeeper” was a wage subsidy and economic support program, announced and introduced as the Covid-19 pandemic broke out, designed primarily to support business and employees through the pandemic’s disruption. At the same time it gave what would have been a faltering economy an immediate fiscal boost of $70 billion, eventually to come to $90 billion. It was a major contributor to the $550 billion net debt that met the Albanese government when it came into office last year.

Usually in a recession the government’s fiscal response includes a significant capital component, but Jobkeeper, and most of the other Covid-19 payments, were recurrent. That is why the current government is correct in stating that they inherited a large debt, without anything to show for it. There were no new assets on the side of the balance sheet.

Treasury commissioned the e61 Institute to evaluate Jobkeeper in retrospect. Its report – Independent evaluation of the Jobkeeper payment – completed in September and recently released, gives the program a positive mark, but with some qualifications.

It was effective in staving off a sharp recession and in providing continuity in employment and business activity. A collateral cost, however, was that it impeded the normal dynamics of a capitalist economy. To quote from the report:

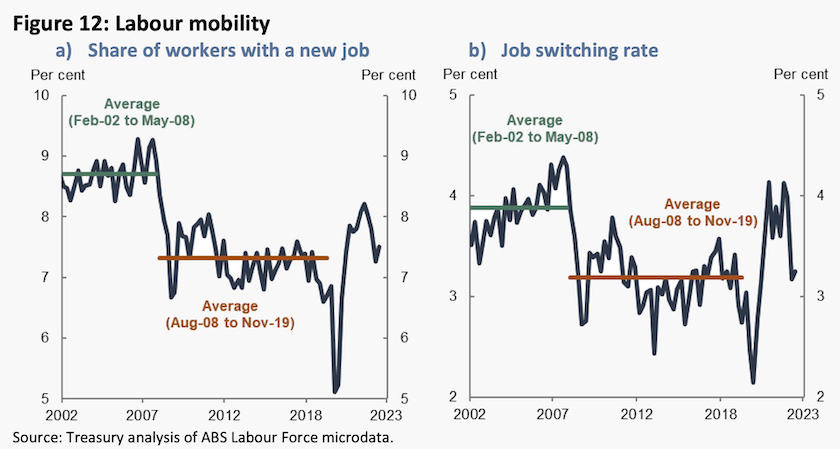

JobKeeper initially had a strong positive effect on productivity by preventing otherwise competitive and productive firms from collapse. Over time, JobKeeper’s distortionary effects – most notably reducing labour mobility and the productive reallocation of labour and supporting unviable businesses – became more apparent.

Two graphs in the report reveal the extent to which labour mobility slowed down after Jobkeeper was introduced, and how it remained sluggish well after the pandemic had subsided.

The authors of the report provide an unconvincing defence for the exclusion of public schools and universities from Jobkeeper. As contributors to the nation’s human capital they could have used Jobkeeper or similar payments to build up the nation’s capital stock and economic resilience.

But as it turned out while education institutions were left out, gambling firms Crown Resorts and Aristocrat Leisure received substantial subsidies from Jobkeeper. (You can download an Excel file of Jobseeker payments from ASIC.) Even more perversely, while government-funded schools were ineligible, some of Australia’s most well-funded private schools received significant amounts of Jobkeeper payments.

It is clear from the e61 Report, as it was from the commencement of the program, that the government was applying value judgements to Jobkeeper eligibility. Prioriting casinos and private schools over government-funded education institutions reveals a great deal about the Coalition’s values.