Other economics

How a chorus of journalists pushed the RBA to raise interest rates

As November 7 approached the odds on an interest rate rise kept on shortening. It wasn’t that new data was revealing a worsening inflation trend. The September quarter CPI was a little above expectations, but as several economists, including John Hawkins and Peter Martin pointed out, CPI inflation has been trending down, and some of the big CPI drivers, such as gasoline and insurance, have little if anything to do with excess demand or a positive feedback loop of rising prices and wages. (See last week’s roundup for their views and reasoning.)

Economists may have been surprised by the rate rise, but most journalists weren’t, because they had been putting a simple story to their readers: inflation is higher than expected, therefore interest rates will rise. Also the story of rising inflation served to reinforce the message pushed by partisan media: your cost of living is rising because the Albanese Labor government cannot manage the economy.

Because journalists were feeding expectations of inflation, the RBA board was in a difficult position. If the public perception was that inflation was rising, was it going to appear weak and do nothing, particularly when it had a new chair?

The RBA’s press release is less assertive than previous releases explaining interest rate rises. It’s almost apologetic in tone. It has the familiar reasons for raising rates, but it also has qualifications:

Inflation in Australia has passed its peak …

While the central forecast is for CPI inflation to continue to decline …

Given that the economy is forecast to grow below trend, employment is expected to grow slower than the labour force and the unemployment rate is expected to rise gradually to around 4.25 per cent. This is a more moderate increase than previously forecast. Wages growth has picked up over the past year but is still consistent with the inflation target, provided that productivity growth picks up.

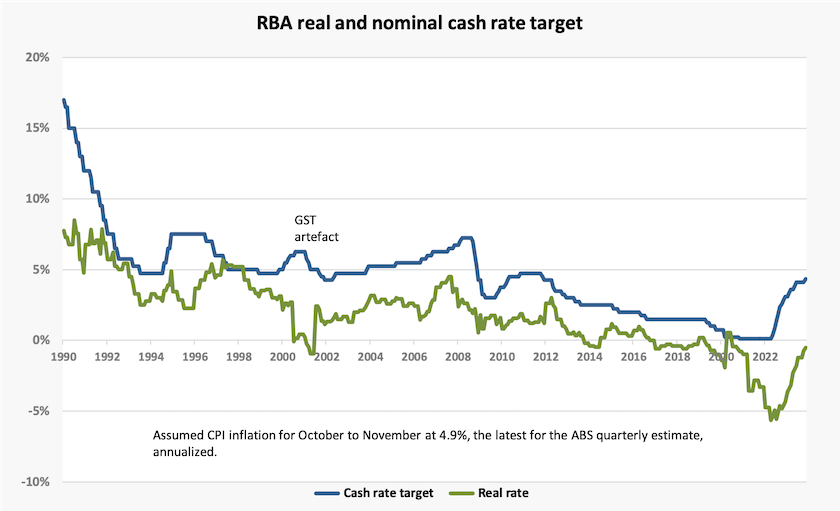

The graph below incorporates the latest RBA decision. Note that the real rate – the rate adjusted for inflation – is now almost back to zero, where it hovered for five years before weird stuff happened to CPI as the pandemic took hold.[1]

Following the decision, Peter Martin, writing in The Conversation, has gone into the possible reasons the RBA raised rates: Why it’s a good bet the RBA’s Melbourne Cup Day interest rate hike will be the last. He struggles to find a good economic reason for the decision, particularly when in the USA, the UK, New Zealand and Canada, rates are being kept on hold as worldwide inflation eases. A reading of Martin’s article conveys the impression that the RBA still doesn’t understand that there is a long lag between interest rate decisions and a reaction from consumers and businesses.

True to form, the Liberal Party had a simple explanation for the rate rise: the RBA was “left with no choice” but to increase rates, because the Labor government wasn’t doing enough to get interest rates down. It’s a common message, rarely challenged by journalists, but in an 11-minute interview on the day after the decision ABC Breakfast’s Patricia Karvelas didn’t settle for this glib assertion.

She consistently asked shadow finance minister Jane Hume what the opposition would do if it were in government. That questioning extracted the reply that it would find savings by cutting public investment in electricity transmission, affordable housing, and industrial reconstruction. Hume then went on to give a pathetic attack on the Albanese government’s response to inflation while comparing it with the Coalition’s response. Her reasoning was along the following line: when the Coalition was in office external factors, particularly oil prices, were driving inflation, meaning that it was not the government’s responsibility, but with Labor in office external factors are simply an excuse for inaction. She defended the Coalition’s decision to cut fuel excise in response to inflation, even though that was a fiscal expansion, actually contributing to demand-side inflation.

If she was sincere in these responses, and was not simply parroting speaking notes prepared by an unschooled party apparatchik, she demonstrated that she lacks the economic competence to hold the office of Finance Minister.

If the RBA is pushing up rates because fiscal policy is too expansionary – a proposition that’s far from proven – there is a solution other than cutting spending. That is to raise taxes, particularly on those who are untouched, or even benefiting from tight monetary policies. So-called “self-funded” retirees enjoying tax-free returns from large superannuation balances, come to mind, as do multinational energy companies. And then there are the promised Stage 3 tax cuts, which carry no benefits for the 47 percent of taxpayers with incomes under $45 000, while lavishing benefits on the 12 percent of taxpayers with incomes above $120 000. These cuts, due to come into effect on July 1 next year, have no justification in terms of fiscal or equity considerations.

1. The real rate should take into account expected inflation – a figure that is not easily determined and which fluctuates widely, but all we have is the lagging indicator of the CPI. ↩

The Optus outage

Optus and the Reserve Bank seem to be running neck-and-neck in a competition to see who can do more damage to the Australian economy.

There are already two Conversation articles about the outage. Three experts in computing and engineering from RMIT and Edith Cowan Universities explain possible causes: Optus blackout explained: what is a “deep network” outage and what may have caused it?. Alison Stieven-Taylor from Monash University looks at the way Optus did everything wrong in communicating with the government, its customers and the public: In a crisis, Optus appears to be ignoring Communications 101.

On the ABC’s 730 program Rachael Falk of the Cyber Security Cooperative Research Centre gave the most convincing explanation of the reason Optus took so long to diagnose and fix the problem: they were almost certainly using the Optus network to try to communicate with one another. A small compensation for the community is the Schadenfreude of imagining frustrated executives staring at “can’t find the server” computer screens and tapping on unresponsive cellphones.

This outage, coming so soon after Optus’ data breach, does nothing for the firm’s reputation. Telstra shares jumped two percent on the morning of the outage. These incidents are strengthening Telstra’s already strong market position: it has always had wide geographical coverage compared with other carriers. Policymakers should be thinking about the possibility of re-establishing the hardware of telecommunications as a single natural monopoly network, probably in public ownership with a technically competent management.

We’re heading out of the capitals but not to the bush

I always have trouble with the way “regional” is used in Australia – essentially to refer to any part of Australia that isn’t one of the capital cities. But if you live in an apartment within cooee of the Melbourne GPO, you are still living in a region, and our capital cities, particularly Sydney, have distinct regions within them: take a drive from Campbelltown to Palm Beach, or from Elizabeth to Noarlunga, if you’re not convinced. And using the term “regional” to refer to the rest of Australia suggests that Byron Bay and Bedourie are more like each other than Byron Bay and Balmain are like each other.

Millennials welcome (Farina SA)

But that’s the classification used by the Regional Australia Institute, whose report Big movers 2023: Regional renaissance, a rise in migration to regional Australia shows that more Australians are moving out of our big capital cities, particularly Sydney and Melbourne.

It was once a pattern in Australia that young people drifted from the country to the capitals, but this pattern has reversed: there is now net movement of millennials (those aged 25-39) out of the capitals. Immigrants too are becoming more inclined to move out of capital cities.

This doesn’t mean we’re heading for the bush. We’re heading to what the Institute calls “regional cities” – cities with more than 50 000 people – and what they call “connected lifestyle areas” – smaller places close to major metropolitan areas. When we move we have a strong preference for the coast, often not far from our big conurbations.

What the Institute calls “heartland regions”, areas isolated from major metro areas, are still losing population. Small settlements in farming regions are collapsing, to the benefit of larger inland cities. This has been happening for many decades as farms become larger and more capital-intensive and as travel becomes easier.

In this context it is notable that the National Farmers’ Federation, concerned about the decline of river communities, is arguing against water buybacks as part of the Murray-Darling Plan to restore the rivers’ health, as if the government’s policies are responsible for this decline. The NFF seems to be reverting to its hyper-partisan traditions.

The RAI report is based on data from the 2011, 2016 and 2016 censuses. We may believe those movement figures were boosted by Decameron-type flights from the pandemic. But the Institute collaborates with the Commonwealth Bank to produce a quarterly Regional Movers Index. Their report for the September quarter 2023 shows that while this movement is now a little smaller than it was during the Covid-19 period, it is still much stronger than in the pre-Covid period. It’s well-established, and as the Institute notes, Covid-19 prompted people in many occupations to find ways to work from home.

The Institute’s main policy message is that governments, particularly the Commonwealth, should be more aware of these movements. They note that the accelerated movement of people out of capitals, particularly millennials, “has strained social and physical infrastructure. For these high growth regions, substantial assessment and investment in infrastructure is needed covering transportation, housing, healthcare facilities, schools and digital infrastructure”.

The Institute does not mention the political implications of these movements. To date it has been a reasonably sure bet that the further a seat is from the state capital, the higher is the Coalition vote. That relationship may be weakening. The Coalition, particularly the Liberal Party, holds a number of rural and semi-rural seats on tight margins. The National Party seems to be more entrenched.

The other general implication is that we would do well to drop the binary classification – capital city vs rest of Australia – to define “regional”. Our social, political and economic landscape is far more complex.

Australia’s “disconnection crisis”

No the disconnection crisis isn’t about Optus. Rather it’s about social disconnection, as Andrew Leigh describes in a speech to the Salvation Army: 140 years of community building.

The first part of his speech is a history of the largely unsung contribution of the Salvos. Leigh then goes on to cite research showing we are becoming more isolated:

Over the past generation, Australians have become less likely to join community groups. Rates of volunteering have declined. The share of people playing team sports has dropped. The share of Australians donating to charity has fallen. Compared with the mid-1980s, the average Australian today has only about half as many close friends, and knows only about half as many of their neighbours.

At the same time inequality has risen. Leigh notes that poverty, in its various manifestations, is linked to disconnection. Those with higher incomes and more years of education are more active in volunteering and in civic or political action.

He goes on to describe how the government is working with the charity sector to help with their work of building social inclusion.

One issue he does not touch on is the way torts lawyers and insurers are inadvertently conspiring to kill initiatives involving community activities. In response to high payouts to claimants of accidents, or to an elevated perception of risk, insurers set unaffordable premiums for liability cover. Often this results in people engaging in less organized and riskier activities, but that is of no concern to lawyers and insurers. In the interests of public safety and social cohesion, there is a strong case for nationalizing public liability insurance.