Australia’s re-awakening renewable energy industry

From the government – an admission that we’re lagging, a pep talk, or both?

Treasurer Chalmers chose energy as the theme in his keynote address to the Economic and Social Outlook Conference last week.

Its tone suggests we’re not on track to meet the government’s stated goals:

… without more decisive action, across all levels of government, working with investors, industry and communities, the energy transition could fall short of what the country needs … we need to get more projects off the ground, faster … we know further action is required to meet our targets.

He summarized what needs to be done in five points, reproduced below:

- While important building blocks are now in place and progress has been made, we will need to do even more to secure sufficient renewable energy generation, transmission and storage to meet our ambitions.

- The availability of public and private capital is a really important issue but it’s not the only issue.

- That means incentives like the type we’ve seen in the Inflation Reduction Act in the United States can be part of an answer but they’re not the whole answer.

- Our industry policy framework needs to be recast and modernised so we can maximise our advantages and leverage our strengths in a new age of net zero.

- The Productivity Commission should and will play a bigger, more constructive role in organising our thinking when it comes to climate and energy policy.

A cynic might observe that the speech is nothing more than a statement of intentions. There is only a hint of new appropriations, similar perhaps to those in the American Inflation Reduction Act, and there is a vague statement about the Productivity Commission having a clearer focus on our progress “towards a successful net zero transformation”.

The ABC’s Tom Lowrey provides some further interpretation from the Q&A session following Chalmers’ speech: Treasurer Jim Chalmers concedes Australia risks missing its climate targets. For example Chalmers suggests that the safeguard mechanism is now working well and needs no changes.

It’s becoming clear that our government sees the US Inflation Reduction Act in terms of its subsidies, which can put Australia at a competitive disadvantage. Chalmers is understandably reluctant to suggest publicly that Australia may have to respond in kind.

Some environmentalists may welcome the idea of national governments engaging in bidding wars to attract renewable energy, but they can rapidly deplete governments’ resources, and as history shows there are no winners in such wars. It would be better if progress towards net zero could be achieved through a price on carbon, which operates through market signals, brings the full cost of fossil fuels to account, and provides public revenue during the transition.

Rooftops to the rescue

At the present rate of expansion of small-scale solar electricity capacity (mainly rooftop), by 2030 we should easily be able to have all of our electricity generated from renewable resources, exceeding our 82 percent commitment.

That is, if we turn off all our lights and appliances at sunset, and if all businesses do the same.

Expensive, unpopular, but necessary

Alan Kohler has a neat two-minute demonstration of how our electricity market deals with an excess of renewable sources during the day and a shortage at night, explaining why we still need fossil-fuel sources for the time being. You have probably heard Coalition politicians patronizingly tell us that because the sun doesn’t shine at night and because the wind doesn’t always blow, we cannot rely on renewables. Kohler however exhorts us to go on putting solar on the roof, and stresses the need for transmission capacity – which is “expensive and unpopular”.

A group of ABC journalists, with help from the Digital Story Innovation team, has prepared a neat infographic presentation about the part renewable energy can play in generating electricity. They illustrate the exponential uptake of rooftop solar (particularly important as large-scale projects stall), they explain the huge gaps to be filled to meet our targets (we need 5 times more rooftop solar and 9 times the amount of large-scale wind and solar), and they describe the transmission infrastructure needed to link demand with sources of renewable supply.

The task of building transmission lines is massive. We have a legacy transmission network based on the location of coal-fired stations, and the Coalition government, in office from 2013 to 2022, had no plan to upgrade the grid to serve the renewables transmission. We are so far behind in developing transmission capacity that we must rely on a great deal more storage, including storage at the household level, in batteries and in electric vehicles.

That will be a huge transition, but it’s doable. The ABC’s Daniel Mercer has a story about an early adapter, Mark Purcell, who has the full kit – panels, an electric car, and a battery – and who has bypassed the electricity “retailers” (coupon clippers who charge a high price for smoothing out the fluctuations in prices) and operates in the wholesale market himself. He claims to be making as much as $10 000 a year in saving and selling energy, a credible figure when one considers how consumer-unfriendly our current tariffs are. (Why do these “retailers” not offer very cheap electricity in the early afternoon, and why do some of them still offer discounts for electricity in the early hours of the morning for hot water?)

On the subject of filling in when the sun doesn’t shine and the wind doesn’t blow, some recommend nuclear power as a reliable, greenhouse-gas-emission-free source of baseload power. There is a great deal of emotional argument around nuclear power – its dangers are generally overstated. But its problem is its economics. Writing in The Conversation – Is nuclear the answer to Australia’s climate crisis? – Reuben Finighan of the University of Melbourne explains the economics of nuclear reactors. Compared with renewables, even when renewables bear the cost of complementary investments to ensure there is continuous power, nuclear power is much more expensive.

Some people hold out hope that small modular reactors could offer low-priced power, without needing the large transmission required by large centralized reactors, but even these don’t stack up economically alongside renewables. The Coalition places small nuclear reactors at the core of its energy policy: it is still hooked on the “baseload power” model. Writing in Renew Economy Giles Parkinson describes how its model project, a plan to the build six 77 MW reactors in Utah, has had to be cancelled because it cannot deliver power at a competitive price, in spite of a generous subsidy from the US government. Coalition’s nuclear SMR poster boy cancels flagship project due to soaring costs. Parkinson quotes Energy Minister Bowen “The LNP’s plan for energy security is just more hot air from Peter Dutton”.

Australia’s re-entry to the renewable supply chain

It is easy to forget that fifty years ago Australian engineers and scientists at the University of New South Wales made a series of breakthroughs that would see photovoltaic cells become a commercially viable way to produce electricity.

The efficiency of solar cells had been creeping up for many years, but it was a struggle to bring that efficiency up to a level that would make electricity generation commercially viable. That was to change between 1974 and 1983 when Shi Zhengrong and others at the University of New South Wales managed to bring up the conversion efficiency first to 18 percent and then to 20 percent, on the way to the present level of 25 percent.

That could have been the opportunity for Australia to develop a large-scale PV manufacturing capacity, but their work coincided with the re-election of a Coalition government. Its priorities were to protect existing industries from import and domestic competition rather than to encourage development of new industries. Shi Zhengrong took his technology to China where he established the firm Suntech Power.

We may now be belatedly taking up that opportunity. On last week’s Saturday Extra – Australian-made solar cell production – Geraldine Doogue interviewed Vince Allen, CEO and co-founder of SunDrive, manufacturing solar cells, the basic component of solar panels. Allen did his PhD at the University of New South Wales, which has sustained its solar research capacity for many years. Along with ARENA (Australian Renewable Energy Agency), Shi Zhengrong is one of the foundation investors in SunDrive. (10 minutes)

As Allen explains, his firm has been able to use copper as a substitute for silver in manufacturing cells. This allows for lower costs, less environmental impact in mining and manufacturing, and greater conversion efficiency.

A basic component of solar cells is polysilicon, a purified form of silicon. Writing in Renew Economy Sophie Vorath reports that Australian-owned Quinbrook Infrastructure Partners plans to build a major polysilicon production plant in Townsville, sourcing high-quality silica quartz (which is currently sent unprocessed to China) from north Queensland: Cashed-up Quinbrook reveals $8bn plan to kick-start Australian solar supply chain .

At the other end of the supply chain, with encouragement from the Tasmanian government, Mike Cannon-Brookes has announced a proposal for his SunCable firm to establish a cable manufacturing plant in Bell Bay, northern Tasmania: A 200-metre tower could be part of SunCable proposal for $2 billion manufacturing plant in Tasmania. These are the cables that would carry electricity from a massive SunCable solar farm in the Northern Territory to Singapore along a 4200 km DC transmission line.

Australia’s contribution to a green future

Rod Sims, now of ANU’s Crawford School, has a Conversation article: Australia’s new dawn: becoming a green superpower with a big role in cutting global emissions. It’s mainly about our opportunities to produce energy-intensive green exports – for example iron and steel reduced from iron ore with green hydrogen.

Unlike our occasional resources booms, which tend to de-stabilize the economy, green exports are likely to find more assured and steady markets.

Sims argues the economic case for subsidising new technologies, but not for subsidising the mining of critical minerals: if the market needs more copper, nickel or cobalt for the global energy transformation it will find the deposits and fund the mines.

How to deal with climate change

Economists want a carbon price

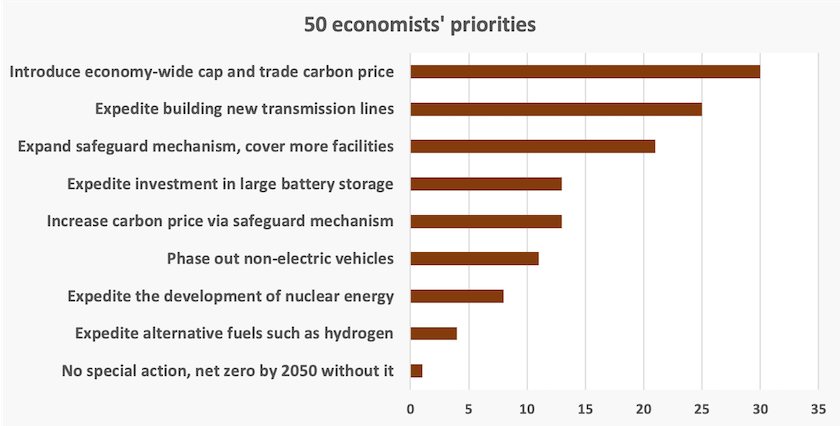

Peter Martin surveyed 50 prominent economists, asking them to choose up to three of the presented responses to the statement “There is evidence to suggest decarbonisation is not advancing at a sufficient pace to attain the government's target of net zero in 2050. In light of this, Australian governments should, as top priorities...”.

Their responses, as published in Martin’s Conversation article, are shown in the graph below:

The one economist who chose “no special action” disagreed with the premise that there was anthropogenic climate change.

Some economists wanted bolder responses than those presented. Banning new fossil fuel projects and imposing green tariffs on dirty imports were among suggestions.

The public want to see strong action but aren’t keen on transmission lines

The Essential Report of 31 October has nine questions on the public’s attitude to climate change policies. To summarize people’s responses, which reveal strong partisan divides:

- After a long period of our believing we weren’t doing enough to address climate change, “not doing enough” and “doing too much” are now about equal. A quarter of Coalition voters believe we are doing too much.

- Among environmental issues we rank “preserving endangered species”, “preserving oceans and rivers” and “preserving native forests” above actions to deal with climate change. This ranking is particularly marked among older Australians.

- Most of us don’t blame the government’s climate change policies for energy price increases. Only 19 percent of us blame “efforts to fight climate change, such as the shift towards renewable energy generation” and a further 9 percent nominate “too many restrictions on oil and gas exploration” as a cause. The rest blame energy companies’ profits, the age of our energy network and international factors. But Coalition voters are much more likely to nominate the government’s policies as the cause.

- About half of us like the idea of nuclear energy for generating electricity. Older people and Coalition voters are particularly well-disposed towards nuclear power.

- Respondents are asked to rank renewable energy, nuclear energy, and fossil fuels in order of cost of delivering electricity. In fact nuclear energy is the most expensive, followed by fossil fuels, followed by renewables, but we get this entirely wrong: we rank renewables as the most expensive, followed by nuclear, followed by fossil fuels. (See the Conversation article by Reuben Finighan for comparative costings). The idea that renewables are expensive is hard to dislodge.

- We like solar farms, windfarms (onshore and offshore), and community battery storage, in that order, but we don’t like overground transmission lines. Coalition voters have the same ranking, but are less enthusiastic about anything to do with renewable energy.

- We generally agree with the statements “Australia needs to ensure that the development of renewables does not come at the expense of local communities”, “Australia needs to make the most of its unique natural resources and weather conditions so it can be a leader in the global effort to address climate change”, and “Australia needs to rapidly develop renewables because it will provide a cheaper and stable energy source, and create new jobs”. But a third of Coalition voters agree with the statement “Australia does not need to transition to renewables”.

- When asked about our trust in government to lead the renewable energy transition, Labor voters show high trust in the government. Greens and Coalition voters are significantly less trusting of the government, presumably for different reasons.

- Only 31 percent of us believe we are likely to reach net zero by 2050, a belief held most strongly by Labor voters.

All these responses suggest that misinformation campaigns on renewable energy have been at least partially successful. In climate change, as in other matters, the Coalition’s anti-science political approach has been effective in attracting uninformed and misinformed voters. Also of concern is the government’s situation, where it is being criticized from the left for not doing enough and from the right for doing too much to deal with climate change: that leads to a complacent feeling that they are sitting in a political sweet spot. (Think Goldilocks.)

It is tempting to believe that concern for climate change is closely aligned with education: surely the more we are schooled in science and the basic techniques of reasoning the better equipped we are to understand the urgency of acting to arrest global warming. But it isn’t quite so simple, explains Jeff Rotman of Deakin University in a Conversation contribution: Our minds handle risk strangely – and that’s partly why we delayed climate action so long. Education does equip us to understand risks, but it also gives us the capacity to rationalize away risk, and to hang on to plausible but unlikely counter-arguments. Not the crazy theories about conspiring scientists, but theories about volcanos, sunspots and a story that there is a scientific study linking whale deaths to offshore windfarms.

Tony Abbott still thinks climate change is crap

See the Betoota Advocate for its survey of retired English-born Australian prime ministers.