Taxes: our civilization deficit

Taxes are what we pay for civilized society – Oliver Wendell Holmes

The Australia Institute’s call for more public revenue

Last Friday the Australia Institute hosted what they grandiosely called a “revenue summit”. In fact it was a series of presentations from politicians, academics, advocates, and experts, mainly about the need for the government to raise more revenue to pay for public services.

The emphasis was on the need for increased public revenue. Apart from detailed consideration of the Stage 3 tax cuts, there was comparatively less discussion about taxes. There was little mention of state and local taxes, or of non-taxation sources of revenue, such as user charges (recently raised in the High Court decision on electric vehicles).

The Australia Institute has a webpage on the gathering, on which most of the presentations are mounted, with video recordings and transcripts.

Ross Gittins has done us the favour of mounting a summary of one of the two keynote addresses, Mike Keating’s, on his website. He covers Keating’s seven reasons why our governments need to collect more public revenue. Some, such as the need to fund aged care, health care and education, have to do with the intrinsic labour-intensity of government services involving human interaction (the “Baumol” effect). Some have to do with demographics – we’re ageing. We are committed to buying some expensive defence kit. And dealing with climate change will require an increase in government outlays.

Gittins doesn’t get on to the ways Keating suggested this shortfall (3 to 4 percent of GDP by ten years’ time) should be financed. In his presentation Keating mentioned six possibilities: using taxes that improve allocative efficiency such as a carbon tax and land tax, applying a higher and wider GST, using resource rent taxes, dealing with corporate tax avoidance, closing capital gains and negative gearing loopholes, and making income taxes more progressive.

Keating’s full speech – A civilized society needs more revenue – is on the TAI website.

These were the main issues discussed at the sessions. Because the Stage 3 cuts are imminent (scheduled to come into effect on 1 July next year) they were subject to detailed scrutiny in two presentations, (which gave the cuts a poor assessment on grounds of equity, allocative efficiency, and fiscal responsibility). Otherwise the prevailing idea was that any tax review needed to be comprehensive, with all sources of revenue in all jurisdictions, on the table. That was the message of the Henry Review in 2010. Because there has been so little progress since then it is still a useful guide for today.

The following sections go into detail about aspects of the session, with references to public finance theory. A starting point is to show where our taxes stand in relation to other countries.

Background: Australia is a low-tax country

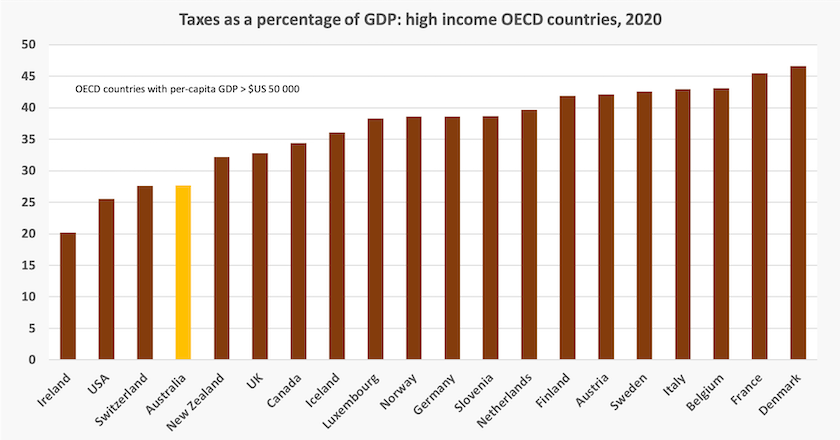

Contrary to some common beliefs, Australia is a low-tax country. At 28 percent of GDP Australia’s taxes (Commonwealth, state and local) are low in comparison with other high-income OECD countries.

In making such comparison, however, it is informative to consider superannuation. While most other countries have social security systems, which are at least partially government-funded, our superannuation system, to the extent that it includes compulsory contributions, is essentially a privatized tax. If we counted these contributions as a “tax”, our taxes would come up to about 32 to 33 percent of GDP, around the same as the UK, but still well below the level in most other high-income countries.

Unlike countries that have large sovereign wealth funds, and some that have highly profitable government business enterprises (rare these days) Australia’s public revenue is mainly through taxation, but the Commonwealth collects non-tax revenue of about 2 percent of GDP (including Future Fund earnings), reported in Commonwealth budget papers.

What – pay more tax?

Many speakers noted the well-known problem in community attitudes to tax: we want more services but we don’t want to pay for them.

When people are surveyed they generally call for more spending on public services. Health and education are the usual priorities, with roads and public transport not far behind on the list. But when asked about whether the government should collect more tax, the answer is usually “no”, or a suggestion that someone else, presently free-riding, should pay. Multinational firms are often nominated in this regard.

One explanation for this paradox is that people don’t trust government to spend taxes in line with their wishes. Several speakers mentioned mistrust in government as an impediment to raising taxes.

Research shows that people are more comfortable about hypothecated taxes and specific levies, than they are about taxes in general. For example there is generally little complaint about the Medicare Levy or the fuel excise – even though in fact these simply go into consolidated revenue, rather than specifically into roads and health care.

Also there is a pervasive belief that a government cannot be elected if people believe it will collect more taxes, a belief that seems to have spooked social democratic parties. Richard Denniss drew attention to the idea in Labor circles that Labor’s defeat in 2019 was a reaction to its tax reform platform, most notably its negative gearing and capital gains tax proposals. (Covered in his closing remarks.)

Yet in that election Labor made significant gains in electorates where people would have been financially disadvantaged by those reforms. These include high-income-high-education electorates, subsequently won by the “Teals” in 2022. In the same election Labor failed to gain ground in traditional working class electorates, where people would have benefited from a Labor government’s health and education priorities. Some speakers suggested that Labor’s 2019 campaign should have had less emphasis on tax reform and more on the benefits that would flow from the increase in revenue.

A similar consideration should apply to political assessment of the Coalition’s often-made assertion that if elected, they would cut public expenditure (an assertion usually made with emotive language about “Labor’s reckless spending”). If journalists were doing their job they would ask just where the Coalition intends to cut, drilling down to specifics if necessary.

The general point, stressed in public finance texts, is that in the public’s mind taxes should relate to benefits. That comes back to trust – many speakers mentioned people’s low trust in government. The public do not necessarily trust the present system where taxes go into one big pool, and in a process known only to Canberra insiders – a process that looks paternalistic from the outside – the revenue so raised is allocated to portfolios and programs. It’s all too opaque. (This is covered under the next sub-heading.)

Maybe this separation of revenue and expenditure has so permeated the Canberra administrative culture that the idea of linking taxation to benefits does not come easily to Labor politicians and journalists.

The budget process – designed to suppress public revenue

Mike Keating was the first to raise the budget process as an impediment to significant reform in collecting public finance.

We might believe that the rational approach for government is to assess what public services and transfers are required by the community, having in mind changing needs, demographics, backlogs in infrastructure and services, and the business cycle. Having assessed these requirements, the government should ensure it is collecting adequate revenue. Many speakers based their arguments for higher taxes on this logic.

But in a longstanding process, adhered to by both Labor and Coalition governments, the budget process starts with revenue. To put it simply, it looks like this:

- Calculate how much revenue we will collect with the current taxation settings.

- Subtract from that how much we will have to spend on demand-driven programs, such as pensions, other transfers and Medicare.

- Allocate what is left over to portfolios, largely leaving allocations within portfolios to ministers’ discretion.

Although governments, for political reasons, may assert that they are aiming for a balanced budget, it rarely works out neatly, even when there is no pandemic upsetting the process. The main point is that the budget process starts with revenue, not needs, and considerations of revenue and expenditure are not closely linked.

For years the Coalition has asserted that Commonwealth taxes should be capped at 23.9 percent of GDP – a figure that has no more justification than Douglas Adams’ 42, but which carries an air of carefully-calibrated precision. Labor is not so specific, bit it tacitly accepts the idea of a cap.

Stage 3 tax cuts

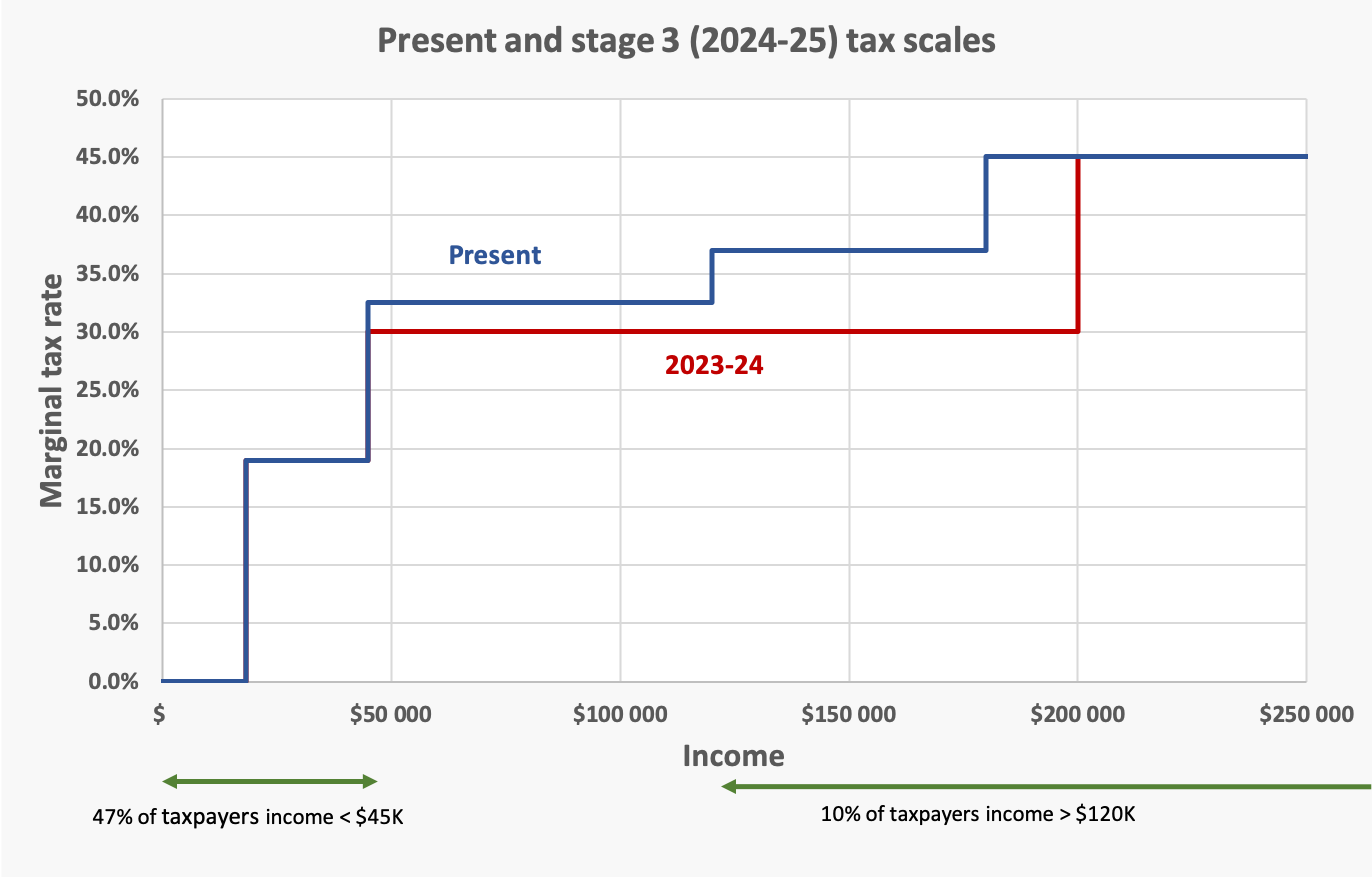

As a reminder, below is a graph comparing marginal tax rates at present with those that would follow the Stage 3 cuts if they are fully implemented.

The case against the cuts hardly needed to be explained. In removing the 37 percent step and flattening the scale the cuts are regressive, and they leave a large gap in public revenue ($320 billion over 10 years).

Much has happened since they were conceived in 2018: the pandemic has increased government debt, real wages have stopped rising, and there has been a rise in inflation, resulting in bracket creep.

At the gathering there was a general consensus however, that having made such a strong political commitment to keeping the cuts, the government cannot simply abandon them. The cuts are easily sold to the electorate on the basis that they involve a tax cut for everyone with an income above $45 000. If they were abandoned it would be easy for the opposition and its media supporters to say that most taxpayers were being denied a cut, even though there would be no cut for those with incomes below $45 000, and only $875, or just over 1 percent of income, for someone with an income of $80 000.

Greg Jericho presented several possibilities for modifications that would preserve progressivity and reduce the fiscal cost of the cuts. In three of the four scenarios he presented there are gains for all taxpayers, not only those with incomes above $45 000. Politically Jericho’s proposed cuts should be easy to promote, because they would benefit those with low to modest incomes, concentrated in outer suburbs where Labor is electorally vulnerable. It should be easy for the government to point out that for most Australians they are offering something better than Coalition’s cuts, which offer nothing or very little for people in these electorates.

To follow Jericho’s presentation, “Stage 3 better”, I suggest you do so through the video recording, where his tables are displayed, rather than the transcript. Anyone who finds delight in spreadsheet modelling can set up models of fairer schedules of tax cuts, plugging in Jericho’s proposals or their own.

Patricia Apps prepared a presentation making the same criticisms, and demonstrating that the cuts incorporated a significant disincentive to work for people trying to move from low-paid work to higher-paid jobs, once the combined effect of taxes and withdrawal of benefits is taken into account. In effect the result is a highly regressive marginal tax rate, and it applies particularly to those who might wish to take on more hours of work. (Apps was unable to attend but Richard Denniss delivered her main points.)

Although the rhetoric from the right is that lowering marginal taxes increases people’s incentive to work, there is no body of research supporting this general proposition. But for some on very low incomes the effect does hold, particularly when there is a substantial jump in the effective marginal tax. Apps pointed out that the people so affected are typically women, in low-paid caring jobs, part-time perhaps, who might lose support for child care as their income rises.

What if the Morrison government had handled the pandemic better?

With the benefit of hindsight it easy to see where all governments could have handled the pandemic better. We don’t have to rely on hindsight, however, to note that its “Jobkeeper” program was unnecessarily wasteful, because the government already had on hand advice that there were better ways to stimulate the economy than handing out money to firms without any conditions – particularly for a government that likes to talk about “mutual obligation”.

Bruce Chapman, architect of the HECS system involving income-contingent loans to university students, demonstrated the savings that could have been made had Jobkeeper been designed on a similar basis, with revenue-contingent loans, using firms’ standard Business Activity Statements. (He stressed the use of revenue, rather than income, because income is too easy to fudge.) He suggested that at least $20 billion of the $89 billion Jobkeeper payments could have been returned to public revenue.

To follow Chapman’s presentation I suggest you do so through the video, which includes his key graphs, rather than the transcript.

Usually when there is a recession or a sharp economic downturn, governments respond with counter-cyclical spending, often involving capital works, such as the Keating government’s One Nation program in 1992 (pity about the name). Such was the onset of the pandemic there was no time to roll out a capital works program. That’s why many have commented that there is nothing to show for the huge fiscal outlays during the pandemic. That is, nothing other than bloated corporate profits and boosted executive salaries. Had the Jobkeeper payments been contingent, as Chapman suggests, there would have been less excess stimulus in the pandemic recovery period and the Reserve Bank could have been less aggressive in raising interest rates.

Multinational tax fairness

Andrew Leigh spoke to the gathering on the need to collect more tax from multinational corporations, and the steps the government is taking to address the problem. His speech is on his website. He explains why technological change has made it easier for multinational firms to shift their revenue to low-tax jurisdictions:

… company taxes are simpler in an economy that makes physical products. Agriculture, mining and manufacturing have clear locations of production. But when a company’s output is digital, it is easier to artificially shift the location of production to the place with the lowest tax rate.

That is in addition to the profit-shifting mechanisms that multinational firms have been using for a long time.

He explained the work of the Tax Avoidance Taskforce and the government’s initiatives to combat firms’ use of thin capitalization, and to require public companies to disclose more of their subsidiaries’ accounts. He also outlined the (slow) progress towards achieving a global agreement on minimum taxation of multinationals.

Consulting firms’ rorts

Senator Barbara Pocock spoke about the behaviour of the Big 4 consulting firms, particularly the conflict of interest revealed in the report of the Senate’s Finance and Public Administration Committee: PwC: A calculated breach of trust. She spoke about the tactics the consulting firms use to enmesh themselves into the government. Her concern is not just about the specific PwC scandal. It’s more generally about how the public interest becomes set aside in development of taxation policy, and the way at the same time the public sector is enfeebled.

She and others in the gathering were outraged at the mild consequences for those involved in the PwC case. The ATO applies inflexible rules to most taxpayers, but for large corporations the amount of tax to be paid is often a matter of negotiation.

Pocock’s presentation – Money for nothing: big consultants and the future of the public sector – is on the Australia Institute website.

Matters only touched on

There were some issues which, in my view, could have commanded more attention:

Wealth taxes. In recent years, while the distribution of income has become somewhat more inequitable, the maldistribution of wealth has become much more pronounced, and as Piketty points out, those with high financial wealth have the means to go on accumulating more. (One comment at the gathering was that in applying assets tests to the age pension and other benefits, we actually apply a de facto wealth tax to people of modest means, but not to the very rich.)

Taxation of retirees. In view of the high cost of concessions for retirees with private superannuation ($21.5 billion a year) much more attention could be given to taxation of those with high superannuation account balances. In this regard Labor’s 2019 proposals on imputation credits were regressive, easily avoided, and would have worsened distortions in the housing market, but much more can be done to bring incomes from retirees’ superannuation accounts in line with taxes applying to people in the workforce. Why should income from investments be taxed more lightly than income from toil?

Trusts. There was no mention of discretionary trusts, the avoidance mechanism of choice for owners of private companies.

Taxation disincentives for long-term investment. Negative gearing and capital gains concessions favour property speculation over real investment. While attention is directed at the economically unjustifiable concessional rate of taxation for capital gains, there is less attention to the Howard government’s decision to abolish indexation of capital gains. This means that long-term investments, particularly those required for our energy transformation, are relatively disadvantaged, and in time could be burdened with taxes on nominal capital gains. The Howard government’s 1999 taxation changes were purposely designed to encourage “financial dynamism” (i.e. churning of assets) to the benefit of the financial sector, at the expense of the real economy.

How to do tax reform

Danielle Wood, CEO of the Grattan Institute, will shortly be taking up her new position as Chair of the Productivity Commission.

She delivered the University of Melbourne Freebairn Lecture on Tuesday, on the theme Tax reform in Australia: an impossible dream. She pulls together the Grattan Institute’s work over many years to argue (once again) for widespread tax reform, and charts a strategy for tax reform that can prevail against the lobbies and political scare campaigns that have successfully thwarted tax reform for so long.

She acknowledges that we need to raise more revenue, and that we need to cut some areas of public expenditure. We cannot go on “asking future generations to bear the costs of today’s inaction”.

Her main argument is about reforming the way we collect taxes. We need to replace taxes that distort resource allocation (such as stamp duties) with taxes and charges that are more neutral or even supportive of more efficient resource allocation. (A carbon tax comes most easily to mind.)

It isn’t for a lack of sound proposals that tax reform has stalled. Rather it’s because there have been effective campaigns against reform. Some of the explanation for resistance lies in partisan politics: she covers political donations and scare campaigns. And much of the explanation is attributable to successive barrages of well-funded third-party campaigns. On these she states:

The perceived success of the mining industry campaign against the Resource Super Profits Tax means threats of a “mining tax-style campaign” have become standard operating procedure for well-resourced groups fighting policy battles.

She explains some of the tactics employed by opponents to tax reform. One is release to the media of hastily-assembled shonky economic analysis, demonstrating for example, that removing negative gearing “would wipe a full $19 billion off GDP”. The sham studies make easy feed for media already carrying an anti-reform bias and employing journalists with little economic education.

She urges us to learn from history. There has been successful tax reform in the past, but it has been a slow journey. She mentions for example the Asprey review, commissioned by the McMahon government, that languished until the Hawke government implemented its reforms 24 years later. It is now 14 years since the Henry Review – we shouldn’t assume its reforms will never be implemented.

She concludes with four recommendations for reformers:

- Put tax reform on the agenda and keep it there. Maybe a crisis will provide an opportunity for implementation.

- Build a coherent package. Don’t rely on sneaky incremental change.

- Embrace the vomit principle. That is to keep repeating the case “until you feel you are going to vomit. Only then are you cutting through”.

- Make it stick. Make sure it is hard to repeal – in a way that the Gillard government didn’t manage with the carbon tax.

Global tax evasion is still flourishing

Shifting reported profits to low-tax havens has been the most common way multinational firms have managed to avoid paying tax. In 2021, as a move to combat this and other techniques used by multinational firms, more than 140 countries agreed to impose a minimum 15 percent tax on multinational profits. The original proposal was for a rate of 20 percent, but this was quickly bargained down to 15 percent.

Since then, through a series of carve-outs, the global minimum tax has been severely weakened, and it may collect only one twentieth of the revenue originally envisaged.

That is one of the main findings of a report by the EU Tax Observatory: Global tax evasion 2024.

It finds that offshore tax evasion by wealthy individuals has shrunk, thanks to better exchange of information between banks, but the world’s 300 global billionaires are still largely untouched by tax authorities, and corporations are still finding ways to shift profits to tax havens.

The EU Tax Observatory recommends renewed effort to raise minimum taxes on multinationals, and a two percent wealth tax on billionaires. In a 30-minute podcast, supporting a wealth tax on billionaires, Joseph Stiglitz explains how one percent of the world’s population has appropriated two-thirds of the wealth created since 2020. The pandemic has both exposed and exacerbated the maldistribution of economic opportunity and wealth. He argues for a wealth tax on grounds of fiscal and social benefits.

The EU report notes that many nations, manly in Europe, are engaged in a competitive race to the bottom, with preferential tax regimes to attract specific socio-economic groups.

In this regard Australia offers a no-questions-asked visa (the 888 visa), with accompanying tax concessions, to anyone who can bring in a few million dollars, a scheme that has been found to bring hardly any net economic benefits (apart perhaps from a boost to dealers in Porsches and Maseratis).

The ABC’s Daniel Ziffer has a summary of the EU report, with an emphasis on its implications for Australia. Based on data apparently supplied by the report’s authors, he notes that Australians hold more than $370 billion in foreign tax havens, costing our public revenue $11 billion a year: Hundreds of billions of dollars held by Australians in foreign tax havens, report estimates.

Taxing the obscenely rich is not just about collecting revenue. It’s also about maintaining the legitimacy of the tax system, and the social contracts that keep society together through shared contributions to the common wealth.