Economics

Is the Reserve Bank behaving more cautiously?

Even though the ABS monthly Consumer Price Indicator for August suggested there has been a slight uptick in CPI inflation, few economists believed that the RBA would raise interest rates.

For the second consecutive month it has kept rates on hold. Notable in this month’s decision is the tone of its press release: its tone is less dogmatic and categorical than those we have seen in previous months. There is an acknowledgement that inflation has passed its peak, and a forecast that it will “be back within the 2-3 per cent target range in late 2025”. Notably, there is no mention of the recent ABS monthly indicator (linked above). As I have often pointed out in these roundups, the headline indicator in the ABS CPI figures is about CPI inflation over the last twelve months, not what it is now.

Two significant contributors to the monthly indicator were gasoline and insurance, while the trend for most other prices was flat or even downwards. There is nothing the Australian government can do about world oil prices, and changes in insurance premiums are mainly associated with climate change and poor locational choices. In fact, in terms of economic efficiency, higher gasoline and insurance prices probably contribute to a more efficient allocation of resources, once the cost of climate change is considered.

In the near future we could see some reduction in meat prices as farmers have been offloading stock, but the conflicts in Israel could result in higher oil prices.

Writing in The Conversation Peter Martin comments on the effect of gasoline prices on the RBA interest rate decision: No rate hike yet, but will it rise on Melbourne Cup Day? It all depends on petrol prices. He points out that, just as higher interest rates act to suppress demand in the Australian economy, so too do higher gasoline prices. That extra we pay at the pump goes out of the country, and comes at the expense of what we have left to spend on other items. Martin’s contribution is a warning to the Reserve Bank to look beyond the simple CPI numbers, and to consider whether price rises will or will not contribute to a positive feedback system of ever-increasing prices.

High gasoline prices will continue to rankle. At around $2.20 a litre Australia’s gasoline prices are very low in comparison with other prosperous countries. In high-income European countries, gasoline is generally priced at $A 3.00 or more. Also Australia has poor motor vehicle fuel efficiency standards in comparison with other countries. In its global fuel economy report, the International Energy Agency reveals that Australia is a country with high fuel consumption and a high penetration of heavy SUVs. These are hard to explain for one of the world’s most urbanized countries and one most adversely affected by climate change.

His other car is an Abrams

The Commonwealth is working on fuel efficiency standards, and has received many submissions calling for an improvement in those standards so as to encourage the uptake of electric vehicles and more efficient internal combustion vehicles. The government seems to be eager to make announcements, but is tardy to act, and the importers of large utes, Ford and Toyota, are pushing for loopholes that will allow them to continue to dump these monsters on the Australian market. Writing in The Conversation Peter Martin asks Where did the cars go? How heavier, costlier SUVs and utes took over Australia’s roads. Martin cannot fathom why anyone would buy such expensive and fuel-inefficient vehicles, but he suggests it may result from an “arms race” phenomenon. Otherwise it makes no economic sense. Is it possible that they have become symbols of identity? Has anyone seen a “Vote yes” sticker on a Dodge Ram 1500 Big Horn truck?

The ABS will release CPI figures for the September quarter next Wednesday, October 25, and the RBA’s next meeting will be on Tuesday 7 November, Melbourne Cup Day. Economic commentators are speculating on the RBA’s moves: the ABC’s Michael Janda has a contribution outlining the developments the Bank is likely to consider in its next two decisions.

Re-thinking full employment: the employment white paper

The government’s promised employment white paper – Working Future: the Australian Government’s White Paper on Jobs and Opportunities – is essentially a textbook analysis of the labour market, out of which emerge a number of what should be uncontentious policy prescriptions.

John Hewson has a short summary – Why full employment is an empty phrase – in his regular Saturday Papercontribution. His assessment is more positive than is suggested by the title, because he stresses the white paper’s message that we have been over-reliant on the headline unemployment rate – the rate that features prominently in the media, in political bunfights, and in the RBA’s announcements. To quote from the white paper:

A broader range of labour market indicators than the national unemployment rate is needed to measure progress towards sustained and inclusive full employment. This includes indicators that capture different groups, regions and aspects of labour market underutilisation.

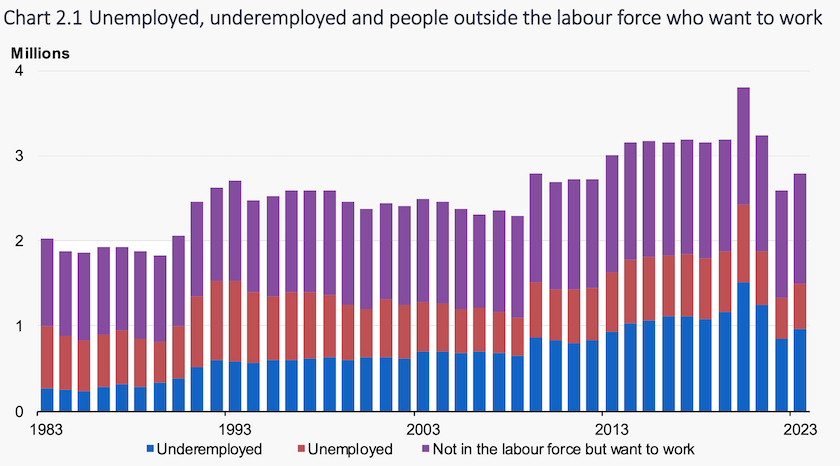

In this regard some of the complexity of the labour market is captured in a chart that shows not only the traditional “unemployed”, but also those who are underemployed and those who are not actively looking for work but who want to work.

Wisely the white paper does not put a figure on what constitutes “full employment”. Rather, it settles on a criterion of satisfying the demand for employment:

The Government is working to create an economy where everyone who wants a job is able to find one without having to search for too long. These should be decent jobs that are secure and fairly paid.

That definition accepts the reality that in a dynamic economy there will always be a certain amount of frictional unemployment, associated with people changing jobs, and with businesses opening and closing. But through education and labour market programs the government is seeking to bring structural unemployment to as low a level as possible, and to lessen the impact of business cycles on unemployment.

That leads back to a discussion about the level of employment that can be maintained without adding to economy-wide inflation – usually indicated by the “the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment”, or NAIRU. The white paper suggests that over the long term NAIRU has been coming down, and with the right structural policies it can be brought down further. Some journalists have suggested that this puts the government at odds with the Reserve Bank but that’s probably reading too much rigidity into the Bank’s recent statements.

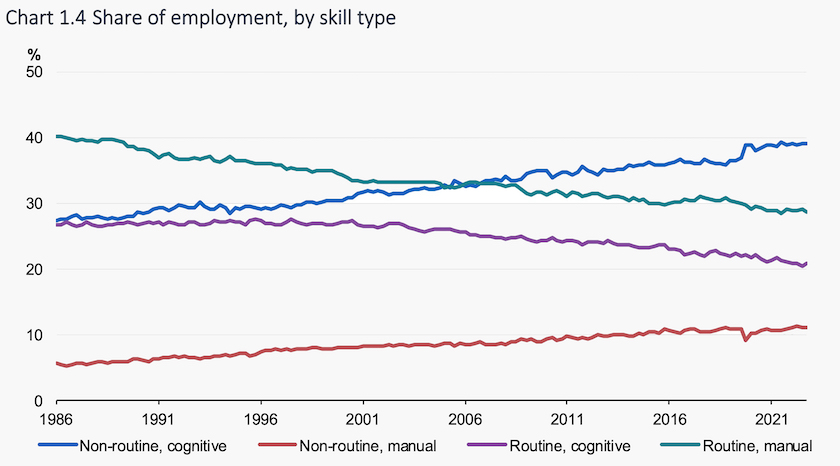

The implications for labour-market adjustment are captured in a graph showing the long-term changing nature of employment, classified by skill:

These long-term changes are quite different from simple ideas about “white-collar jobs displacing blue-collar jobs”: in fact the trajectory of “non-routine manual” employment is much more promising than that of “routine cognitive” employment. Those trends should continue as the economy, and therefore the labour market, adjusts to “five forces” that will shape the economy. These are:

population ageing, rising demand for quality care and support services, expanded use of digital and advanced technologies, climate change and the net zero transformation, and geopolitical risk and fragmentation.

The white paper avoids listing specific skills, but it puts a great deal of emphasis on the need for institutional barriers to skills development to be broken down, and for people to take on new skills throughout their working lives. There should be more integration of our vocational and higher education sectors, for example.

If the economy of the future is to provide well-paid and meaningful work, there has to be a resumption in productivity growth. All prosperous countries have suffered a decline in productivity, but Australia’s productivity performance has been poor. The white paper mentions in particular a slow diffusion of innovation and a slow uptake of technology, most notably in service sectors. It paints a picture of an economy in which firms are making easy profits without having to work for them. That’s “symptomatic of declining competitive pressures which have also contributed to slowing investment growth, and the slower pace of labour and capital reallocation towards higher productivity firms”.

One issue the white paper ducks is the poor performance of privatized employment services. In 1998 the newly-elected Howard government, driven by a determination to cut government services regardless of the economic consequences, abolished the Commonwealth Employment Service (CES), a nation-wide service that matched employers to job seekers. The white paper acknowledges that the privatized model has performed poorly for job-seekers (although it has delivered high profits to the employment service companies), but is short on suggestions on ways to restore a low-cost and effective service.

Writing in The Conversation David O’Halloran of Monash University notes that there are calls to re-establish the CES. His article Please don’t bring back the Commonwealth Employment Service outlines the shortcomings of the present system, particularly in the way administration of the Commonwealth’s punitive “mutual obligations” requirements conflicts with the need to place job-seekers. As the title suggests, however, he does not want to see the CES re-established. His reasoning is that the Commonwealth has been stripped of the capacity to run services.

That’s a valid point, but it is somewhat defeatist to suggest that we cannot re-build what the Howard and successive Coalition governments destroyed – a competent and professional public service. The CES gave the Commonwealth a visible presence in suburbs and country towns, where it was providing a useful service. It may be politically wise for the Commonwealth to consider not only public service reform, but also its distribution throughout the land.

Productivity and wages – who shares the benefits?

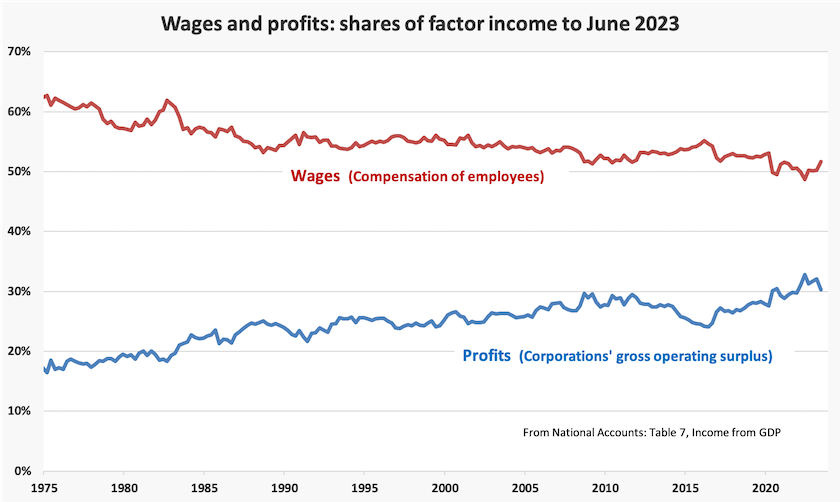

On this site we have often displayed the long-term trend in wages and profits, showing that, over a long period, an increasing share of national income has been accruing to profits at the expense of wages.

The latest instalment, up to June this year, is shown below. Note that there has been a small uptick in the wages share in the latest period but the trend is towards profits.

In a short research paper – Productivity growth and wages – a forensic look – the Productivity Commission has looked at how the gains from productivity growth have been distributed between wages and profits since 1995. It finds that over this period there has been some “decoupling” of productivity and wages – 0.6 percentage points a year, meaning that each year, on average, the wages-profit share has moved 0.6 percent in favour of profits. Most of the fall in the share of income going to wages has been in two sectors – mining and agriculture.

The Commission’s conclusion is that “over the long term, for most workers, productivity growth and real wages have grown together in Australia”, and that “in all industries outside of mining and agriculture, which account for over 95% of employment, the difference between productivity growth and wages growth has been relatively low”.

It is informative to dig into the Commission’s sector-by-sector data. It shows that in some sectors – professional, scientific and technical services; construction; transport, postal and warehousing; financial and insurance services; accommodation and food services; manufacturing – there has been 0.5 percent or more de-coupling. That may not mean much when productivity growth is bubbling along at a high rate, but when it is down around 1.2 percent a year, there isn’t much left over for wages.

On a related matter the ABC’s Markus Mannheim reports that Commonwealth public servants’ pay has shrunk in real terms over the last two years, and that their pay is substantially lower than what is paid for similar jobs in the private sector. Mannheim’s report provides some figures by public service pay grade, but the data on which his article is based is behind a corporate paywall.

Qantas – all the worst business behaviour in one company

For business school lecturers seeking case materials for students, Qantas is the gift that goes on giving. It has brought to our attention the worst of business behaviours and the way governments have privileged the interests of businesses over consumers.

The media has given a great deal of attention to the way Qantas acted illegally in sacking 1700 ground staff and cleaners during the Covid-19 pandemic. This is not only about the legal issues involved: it’s also about the way management viewed the firm’s workforce as a cost centre rather than as stakeholders and as core assets.

As the ABC’s Peter Ryan explains, in this outsourcing, in selling tickets for flights it never intended to operate, and in rewarding its CEO and other executives with obscenely generous bonuses, it has trashed its social licence: Qantas' High Court loss further erodes a reputation already in tatters — and perhaps beyond repair. Because a firm’s reputational capital doesn’t appear on any balance sheet it’s easy for an opportunistic management team to spend it down. By the time the damage is manifest – usually in terms of loss of customers and a de-motivated workforce – the managers have moved on, having banked their bonuses and are ready to do the same to another corporation.

Then there’s Qantas’s relationship with government. You can hear Transport Minister Catherine King in an interview with Laura Tingle providing her reason for refusing extra flights to Qatar, simply saying it would not have been “in the national interest” to have allowed Qatar extra flights.

That’s inadequate accountability by any standard. Even at the height of tariff protection there used to be disclosure of the reasons the government gave firms protection, but when it comes to aviation the only reasoning we hear from the minister is that liberalization is not “in the national interest”. Nor is there much disclosure about how landing slots are allocated.

The issue of slot allocation is addressed in the government’s Aviation Green Paper. Its rhetoric aligns with sound economic principles:

The Australian Government is actively seeking outcomes that deliver a more competitive aviation sector, while at the same time securing Australian jobs and is interested in stakeholder views on options to improve competition and market outcomes in the sector.

The Qatar decision prompted the Senate to hold an inquiry into bilateral air service agreements. Alan Fels took the opportunity to appear before the Senate committee to draw attention to Qantas’s “dramatic misuse” of its capacity to lobby government. He noted the way slot allocation suppressed competition, and he noted that the Green Paper “leaves things a little bit too open to the impact of lobbying”. Amelia McGuire, writing in the Sydney Morning Herald, suggests that the government may be moving towards reforming slot allocation.

More generally in its narrow focus on “aviation” the Green Paper fails to address the general competitive environment for travel in Australia. Successive governments, Labor and Coalition, have baulked at investing in high speed rail. They justify their rejection of rail investment by using costing methodologies that overstate the government’s cost of capital and that understate the cost of air travel, particularly the cost imposed by airlines’ unreliability. Such is the convenience offered by reliable rail travel that France, for example, has been able to ban short-haul flights where there is a rail alternative of 2.5 hours or less.

Qantas’s status as a sacred institution is illustrated by revelations about the way it gives politicians and senior public servants membership of its exclusive Chairman’s Lounge. Much media commentary has been about the supposed unfairness of such perks. But that’s not the issue: those who have to travel frequently surely deserve some comfort. Rather the issue is that these lounges isolate ministers and public servants from the general public, and they provide a venue for quiet agreements between mates. Ministers would do well to use air travel as an opportunity to mingle with the hoi polloi in a safe environment.

Neither the Minister nor Qantas management have been brought to account for the Qatar decision. Sarah Basford Canales writes in The Guardian about the political processes that have allowed them to avoid scrutiny, but with the help of independent Senator David Pocock a deal has been brokered which will see the ACCC resuming its role in monitoring air passenger services – a role it had during the Covid-19 period.

Qantas, PwC and the rest of corporate Australia: Australian capitalism is on the nose

Corporate Australia has been in the news lately for many of the wrong reasons. Qantas, PwC, Rio Tinto, Optus, Medibank, Harvey Norman are some of the names mentioned by Roy Morgan in its monitoring of the extent to which people mistrust corporations.

Their findings reveal that “Australians have never been more distrusting of corporate Australia since Roy Morgan began measuring trust and distrust in late 2017.” The ABC’s Gareth Hutchens, in reporting on the Roy Morgan survey, suggests that voters are distressed by the “moral blindness” of corporate Australia.

Commenting on Ziggy Switkowski’s condemning report on PwC, and on the Morgan findings, Carl Rhodes of the University of Technology, Sydney, writes that Beyond the PwC scandal, there’s a growing case for a royal commission into Australia’s ruthless corporate greed.

Last October the Senate established an inquiry into the “capacity and capability of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission [ASIC] to undertake proportionate investigation and enforcement action arising from reports of alleged misconduct”. Inquiry Chair, Senator Bragg (Liberal, New South Wales), has drawn our attention to ASIC’s poor and deteriorating performance in bringing corporate misbehaviour to account. The data suggest “that ASIC has made Australia a haven for white-collar crime” and that “ASIC has given up on their sole obligation to enforce corporate law”.

Corporate malfeasance generally comes to the attention of law-enforcement agencies through whistleblowers, but in Australia whistleblowers receive little support. Writing on the ABC website investigative journalist Adele Ferguson, drawing on the ASIC inquiry and other cases where whistleblowers have been treated badly, writes that the ASIC Senate inquiry delivers a reminder that whistleblowers should be protected, not punished. Ferguson notes that in opposition Labor had promised to protect and reward Australians who blow the whistle on crime and corruption, but in office it has abandoned this promise. You can also hear Ferguson in a 6-minute interview on ABC Breakfast, in which she describes one whistleblower’s frustrating and costly effort to bring corporate misbehaviour to ASIC’s attention.

On his Policy Post Martyn Goddard writes on the increasingly unacceptable faces of capitalism. Goddard describes the failure of capitalism, in America and Australia, to achieve a fair distribution of the benefits from economic activity. The beneficiaries of economic growth have been corporate executives and the owners of firms that have managed to secure a privileged position in the market place. As firms accrue monopoly profits their capacity to use some of those profits for influencing government is strengthened.

In pointing out how the excess profits from rent-seeking behaviour leads to a positive feedback cycle of ever-increasing monopolization, Goddard is confirming the work of Mancur Olson in his 1982 work The rise and decline of nations: economic growth, stagflation, and social rigidities. Olson’s ideas were influential in shaping the Hawke-Keating government’s approach to structural reform.

The Qantas, PwC and other cases illustrate three trends in corporate behaviour that have become pronounced over the last forty years, captured in a quote from a respondent to the Roy Morgan survey: “The CEO is a disgusting greedy individual, who is a poor employer, makes use of people, governments and society for his own personal aggrandisement.”

One is the pursuit of profit as an end in itself. The theory of organizational behaviour used to be that firms sought profit as a means to an end, that end being the ongoing strength of the firm. But in the 1980s business schools and consulting firms switched that thinking around and making a profit became the end in itself. The path to profits was through acquisition of under-valued firms, rather than creating value through real investment, a strategy that may yield short-term profits, but eventually suffers the unsustainability of parasitic behaviour.[1]

A second trend, also recorded in business schools, is the growth of what is known as “managerial capitalism”, where the senior manager becomes one of the major beneficiaries of corporate surpluses.[2] (Note that statistically bonuses paid to executives count as returns to labour.) Business schools changed from academic institutes studying corporate behaviour to training grounds for executives.

The third trend, related to the second, was the rise of the authority of the CEO. The idea of corporate management as a team effort, overseen by a diligent board, became unfashionable. In many corporations the CEO became the corporate equivalent of the strongman dictator in countries that had drifted from democracy to authoritarianism – with the same consequences as we have seen in recent cases.

1. This philosophy was captured in the 1979 work by Malcolm Salter of the Harvard Business School and Wolf Weinhold of the Sloan School of Management Diversification through acquisition. It carried the deceptive subtitle “strategies for creating economic value”, but it was really about the parasitic practice of relying on others to create value. ↩

2. See Alfred D Chandler Jr and Richard S Tedlow The coming of managerial capitalism: a casebook on the history of American economic institutions, 1985. ↩