The Voice

Although the outcome was a confirmation of opinion polls, there was still a sense of shock and disappointment, particularly among indigenous communities who saw the outcome as a rejection of the generous invitation extended in the Uluru Statement.

In the immediate reaction there have been strong assertions: reconciliation is dead, constitutional change is impossible, Australia is/is not a racist country, the response was an emphatic “no”/in spite of a dirty campaign four out of ten Australians supported the referendum.

Categorical claims and explanations based on single causal factors do not help us understand the complexity of the outcome. Nor do they help those who seek to resume the task of reconciliation and to sustain our democracy in the face of an assault from those who have ramped up the use of lies, confusion and disinformation as political weapons, rather than engaging in arguments about policy.

In this roundup I have three separate, independent entries:

- How we voted – as revealed in electorate and booth results, although it will be some months at least before there is more thorough analysis available;

- Why we voted the way we did – seven possible contributing factors to the outcome, based on polling and the opinions of those observing the political landscape;

- The political consequences – in terms of electoral processes and outcomes.

How we voted – education and echoes of the 1999 republic referendum

Almost before Antony Green’s computer had cooled down, the ABC Story Lab produced a graphical display of the referendum outcome: Beyond No, here’s what we know about the Voice results.

Four scatter diagrams illustrate our voting patterns:

Where we live – the closer we live to our state capital, the more strongly we voted “yes”. (Note that the graph has a logarithmic X axis; even by 10 km from the CBD the “yes” vote has lost ground.)

Educational achievement – if our schooling didn’t go past high school we were less likely to vote “yes”.

Age – younger people were more likely to vote “yes”.

Income – the higher our income, the more likely we were to vote “yes”.

All these variables relate closely to one another. When one looks at the scatter diagrams, education seems to display the strongest correlation, while age shows the weakest.

A strong correlation does not necessarily indicate causality. It may be that those with more education have more knowledge of our history, are more capable of seeing through lies and logical fallacies, are more knowledgeable about democratic conventions, or are less attuned to social media. One does not need a university degree, however, to develop these capacities.

The team’s other revelation is the similarity of this outcome to that of the 1999 referendum on an Australian head of state. Those who voted “no” in that referendum voted “no” for a Voice. As the team puts it:

Despite all the differences between the two referendums — the same areas that were resistant to change, and those that embraced it, have hardly shifted at all.

Another presentation of the results is provided by the ABC’s Casey Briggs, who has presented maps of the outcomes in urban areas. These illustrate what Antony Green was pointing out on the night of the count: the prosperous urban electorates that turned to independents and the Greens in last year’s election also recorded a strong “yes” vote.

Not revealed in this early analysis is any indication of how indigenous Australians voted. In view of the “no” campaign’s assertion that indigenous Australians are divided – a division nudged along by a handful of prominent aboriginal “no” campaigners – it is important that this question is settled.

Because most indigenous Australians live in big cities and inland towns, there is no way basic election data can reveal how they voted. In time the ANU Centre for Social Research and Methods will probably apply techniques of multivariant regression to provide some reasonably robust analysis. But we do have results from remote communities which are overwhelmingly indigenous. Casey Briggs presents these results, indicating that indigenous Australians voted strongly in favour of the Voice, with support up to 75 percent. Jordyn Beazley, writing in The Guardian – Indigenous communities overwhelmingly voted yes to Australia’s voice to parliament – presents a similar analysis, including some interpretation, such as the observation that “In Yuendemu, the community home to the family of Price, shadow minister for Indigenous Australians, three in four people voted yes”.

Why we voted “no”: seven possible reasons

The media is overwhelmed with theories about why we voted “no”. It will take time for the dust to settle and for serious evidence-based analysis to be produced.

We do know that while early polls were showing around 65 percent support for the proposal, support started to fall early this year, coinciding with Dutton’s deceitful assertions about the referendum’s lack of “detail”. When support falls from 65 percent to 39 percent (the actual vote), the effectiveness of the “no” campaign stands out as a most likely explanation, although Kos Samaras, in an interview on Saturday Extra on the morning of the vote, suggests that the “yes” campaign could have done far better.

Early on it became obvious that the “no” campaign had no intention to engage in a debate on the merits or otherwise of the referendum proposal. The Coalition, in a conservative tradition, could have mounted a reasoned argument against the proposal, on the basis that over time the problems of identifying aboriginality could make for difficulty in determining a franchise for the Voice. Instead it pursued a campaign of deception, misinformation and deliberate confusion. In a Saturday Paper contribution, where she clearly anticipated a defeat, Marcia Langton accuses Dutton of injecting “fear and race hate” into the campaign, and of lying about detail.

Some may consider Langton’s claims to be exaggerated, but the last Essential poll before the referendum specifically surveyed “no” voters about their reasons for rejecting the proposal. “It will divide Australia in the constitution on the basis of race” was the response by 42 percent of “no” voters, followed by “There is not enough detail on how the Voice will work” (26 percent). Dutton’s tactics were working.

These, and other reasons for voting “no” are covered below.

“Race” – the toxic legacy of a morally indefensible idea

The historical idea that humans could be classified by “race” was a convenient justification for slavery, and in Australia’s case a justification for the White Australia Policy. It has no basis in science however.

Unfortunately the idea of “race” lives on. In the USA the idea of “race” allows the hard right to attribute the plight of Afro-Americans to some imagined genetic factor, rather than the legacy of slavery and Jim Crow laws. The soft left refers to “people of colour”, as if there is some quality, other than shared humanity, linking Rishi Sunak with a Somalian subsistence farmer, and as if so-called “people of colour” have not themselves been engaged in slavery and colonization.

Writing in the Saturday Paper about the reasons people intended to vote “no”, Rick Morton reports on focus group research revealing a fear that “the Voice would elevate one race above others” – a finding in line with the Essential survey.

It shouldn’t be necessary for anyone to debunk the idea of “race”, but in his Press Club Address For the love of country (a powerful moral argument for the Voice) Noel Pearson dealt with the issue in response to a consistent line by Murdoch journalists, conflating the ideas of “race” and aboriginality. His response:

We’re humans. It’s just that we are indigenous. And you go to some parts of the world and indigenous people are blond and blue-eyed. It’s not about race. This is about us being the original peoples in the country.

They [Janet Albrechtsen and Andrew Bolt] have never admitted to that misrepresentation. It has been in their interests to conflate the two things: race and indigeneity. It’s crucial to their campaign.

But I would ask Australians to understand that this is not about race, this is about indigenous. And the simple question about indigenous is: were there peoples here before 1788? And the answer is yes. There were Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders, and that’s what we’re recognising. Not a separate race.

Pearson argued that the Constitution should recognize that Australia was not “terra nullius”, but was inhabited by indigenous people, and that Australia should celebrate a people and culture that had survived and thrived for 60 000 years. This has nothing to do with “race”.

It’s not only a few Murdoch journalists who were running the “race” line. Warren Mundine, Jacinta Nampijinpa Price and many prominent Liberal members of Parliament have consistently talked about the Voice defining Australians by “race”, and only on a few occasions did ABC journalists pull up “no” campaigners who described the original owners of the land as a “race”.[1]

Those who live in “settler” countries such as Australia should be reasonably familiar with the idea of aboriginality, but maybe for others it is not necessarily a familiar concept. The Australia Institute published a survey revealing that those not born in Australia were slightly more likely to vote “yes” than native-born Australians, but perhaps these results were simply revealing differences in age and education among immigrant Australians. On the night of the count Antony Green noted that some of our immigrant regions in outer suburbs returned a strong “no” vote. We should not be surprised if research reveals that different immigrant communities voted different ways, because over time the composition of immigration has changed.

While many may have voted “no” because they believed they were rejecting the idea of a racial division, we have to acknowledge the uncomfortable reality that there is racism in Australia, including racism directed at aboriginal Australians. Just ask any member of the campaign who received threats and abuse, generally in the cowardly anonymity of social media, to recount their experiences.

John Hewson, in his regular Saturday Paper contribution, has written about The enduring stain of the White Australia policy. Anyone who came to Australia between 1901 and around 1975 came to a country that defined itself as “white”. That was so until less than 50 years ago, and it is probable that for many, White Australia was itself an attraction. There is a message in the age profile of the vote: if some older generations are finding it hard to shake off the idea of Australia as a home for the “white”, racism may be with us for some time yet.

The story from people manning booths is that while many “yes” voters revealed their intentions, few “no” voters were willing to disclose their vote, and a casual observation confirms that many more people were prepared to wear “yes” t-shirts than were ready to wear “no” t-shirts.

The government would have done well to have included in the referendum deletion of the two mentions of “race” in the Constitution, or to have changed the wording to “indigenous” or “aboriginal” people. That would have sent a strong message to those who, deliberately or in ignorance, conflate “race” with aboriginality.

Poor understanding of democratic institutions

Had the government provided details of its proposed legislation, Dutton and his colleagues would have found plenty of points to quibble about and to object to.

Regardless of the political consequences, it would have been quite inappropriate for the referendum’s proponents to conflate the idea of a constitutional provision with legislative processes. In focusing on the simple question in the referendum the government was acting entirely in line with the conventions of a democracy with a written constitution.

Kos Samaras believes the government should have provided more detail, but surely that would have added to the confusion: would people be voting for a constitutional amendment, or giving their views on legislation? We don’t make laws by plebiscite.

In a Guardian article – Going by no voice campaign’s arguments, federation itself would have been defeated – constitutional expert Anne Twomey explains how little we understand about our constitution, and how myths have developed about its provisions. It does not specify that everyone should be treated the same, and it contains as little detail as is necessary, giving lawmakers the flexibility to implement policy and to change policy provisions over time. (Fortunately Peter Dutton wasn’t around in 1901: if he were the vote to adopt the constitution would have failed and we would still be six British colonies.)

Tony Nutt, a former federal director of the Liberal Party and chief-of-staff to John Howard, was quick to point out the fallacy in the call for “details”, but his reasoning fell on deaf ears in the inner core of the Parliamentary Liberal Party.

Dutton’s ability to run the “details” argument exposes a fragility in our democracy.

A well-informed electorate, understanding the separation of constitutional, legislative, executive and legal powers, would have dismissed his line about “details”, but for a substantial proportion of the electorate he has gotten away with this deception – just as he got away with his outrageous assertion a few years back that Parliament is a disadvantage tor governments.

Our collective ignorance about the workings of democracy makes the way open for populist demagogues to take advantage of that ignorance. Dutton himself may be a passing phenomenon, but he has exposed weaknesses that can be exploited by even more ruthless politicians. His “if you don’t know, vote no” message was a call for people to disengage from democratic processes – a disengagement that historians recognize as a first step towards totalitarianism.

The idea of “privileged” Aboriginals

It is extraordinary that the Coalition spokesperson on Indigenous Affairs, Jacinta Nampijinpa Price, was able to say that indigenous Australians suffered “no ongoing impacts of colonisation”.

She seems to be guided by a morality that puts Land Cruisers, supermarkets and running water on one side of the ledger, and the legacy of massacres, displacement from country, deracination, and abduction of children from their families on the other side, and with a little arithmetic she calculates that for indigenous Australians the outcome is a net positive.

This is the same hyper-utilitarian framework that underpinned the Soviet Union in its most brutal period.[2]

By any calculation, even on utilitarian grounds, indigenous Australians are disadvantaged. Yet, according to the Essential poll, 14 percent of “no” voters believed that the Voice “will give Indigenous Australians rights and privileges that other Australians don’t have”.

In Anne Twomey’s article, referenced above, she refers to the common belief that our constitution and established conventions rule out special treatment for any group. But the reality is that there is no such constitutional provision, and there are numerous public policies that make provision for specific groups, particularly those who are disadvantaged in some way – the unemployed, people with disabilities, retirees with inadequate means. And when it comes to voice the various industry lobbyists, from energy corporations through to pharmacists, have well-established voices, generally financed by tax-deductible contributions to industry associations.

History gaps

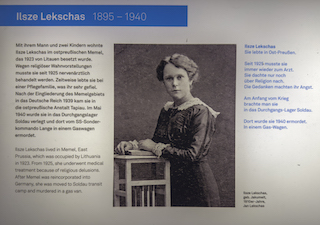

In Germany one cannot avoid reminders of the Holocaust and other atrocities of the 1933-1945 era. On a Berlin sidewalk a pedestrian is confronted with an illuminated plaque, reminding one of the fate of Ilsze Lekschas, murdered in a gas van in 1940. In a country village one may encounter a Stolperstein (literally a “stumble stone”) in the pavement, a small memorial to a Jewish family who once lived in a nearby house before being murdered in Auschwitz.

One of many historical reminders

John Howard might accuse Germans of having a “black armband” view of history, but that armband has helped Germany solidify its democratic institutions, in ways that neighbouring countries, such as Hungary, have not.

In relation to aboriginal people, the USA is way ahead of Australia in recognizing its violent history. It would be hard for any American not to know about the Wounded Knee massacre, for example. A Wikipedia list of Australian massacres is no less confronting than its North American equivalent, but in USA and Canada there is more local awareness of this history.

In Australia we can pass through places where there have been massacres, unaware of the terrible events that have taken place. Family histories refer to people in the nineteenth century who “took up” land, without reference to those whose land it was before.

On a Late Night Live program we can hear Henry Reynolds reflecting on the extraordinary gaps he discovered in Australian history telling. Our school history books have started to fill in those gaps. Most older Australians, however, grew up with school history curricula that mentioned indigenous Australians only in passing, and apart perhaps from a mention of the Myall Creek massacre (atypical only in the fact that seven of the murderers were punished), that ignored the brutal aspects of our history.

Perhaps the authors of the Uluru Statement got the order wrong: truth-telling may be a prerequisite for reconciliation.

It’s a Canberra thing that has nothing to do with ordinary Australians

A quiet campaign outside the big cities

The state-by-state outcome, revealing that only the ACT recorded a “yes” majority (61 percent), tended to confirm the idea that the Voice was something cooked up in Canberra by so-called “elites”.

But a glance at the electorate results debunks this idea. If one goes to the website of results, by electorate, and chooses a sort by “highest yes”, it is evident that the outcome in the ACT was typical for urban areas. Inner Melbourne and Sydney electorates, in fact, had a higher “yes” vote than the ACT’s electorate of Canberra, the most central of the ACT’s three electorates.

There was also the idea that the aboriginal people who coordinated the Uluru Statement and who so strongly advocated for “yes” were some Canberra elite disconnected with the indigenous people living a tough live in the outback. That idea is negated in the results from remote booths.

But it is does seem to be correct that many people, most notably those living in regions distant from state capitals, were not connected with the campaign. Waleed Aly picks up that mood in an article by Joshua Haigh The Project’s Waleed Aly says less educated Aussies voted No to Voice.

That headline seems to align with the idea that the bush is populated by people who lack the intelligence to be involved in politics, but nothing can be further from reality. Country people tend to be passionate about local and state politics, and are keenly aware of where their taxes are going. Age (country people are older), the difficulty of accessing good schooling, and state governments’ policies on allocating education, all have a lot to do with lower education qualifications in the country.

It’s only an anecdotal observation, but in the week before the vote I was in central-western New South Wales, an area with significant aboriginal populations, and found hardly any awareness about the referendum. There was no observable “yes” or “no” campaign, and there was not a corflute in sight. As Waleed Aly and Kos Samaras suggest, the “yes” campaign failed to connect with outer-suburban and non-metropolitan Australia. Politicians and advocates may have visited these regions, and advocates may have engaged in cold calling and doorknocking, but people see a political campaign in transactional terms – the political equivalent of the door-to-door encyclopedia salesman. Connecting with the community takes a long period of patient work, as independent members of parliament in rural seats confirm.

Fear and confusion

The organization calling itself “Advance”, closely aligned with the Liberal Party, specifically told its volunteers to use “emotive language”, to avoid “facts and figures”, and to hammer into voters feelings of “uncertainty, of doubt or fear”.

In trashing the rules of civilized political argument they unleashed a wave of vile behaviour. Nazis emerged with a ghastly attack on Lidia Thorpe and a burning of the Aboriginal flag. “No” campaigners desecrated a war memorial. A soap opera celebrity spread a conspiracy theory about the Voice leading to a UN takeover. We were told white people would be paying to live here if the referendum were to succeed.

Conspiracy theories extended to paranoid ideas about the Electoral Commission: voters were issued with pencils so that the Commission could erase “no” votes and replace them with “yes” votes.

Of course Dutton and his colleagues publicly distanced themselves from the most extreme of these behaviours, although at one stage they did suggest that the Electoral Commission was biased to a “yes” outcome. But in a tactic reminiscent of Hitler’s early rise to power, and more recently of Trump’s political tactics, they blamed the “yes” campaign, rather than their own provocations and inflammatory language, for causing division.

Social media have undoubtedly provided a vehicle for spreading fear and misinformation, but is it any more effective in doing so than some of the older media it may have replaced? In time there may be some analysis of its influence in this campaign from the University of Canberra News and Media Research Centre.

The Murdoch media generally ran a consistent “no” campaign. That bias we can easily identify. But even the unaligned media added to fear and confusion. The issue at stake was simple, but journalists are always eager to find some new angle: they don’t get paid for repeating the same simple story. Each new angle, no matter how peripheral, added to confusion. Then there was the ABC obsession with “balance”, an issue noted by Laura Tingle, which gave a pulpit to some way-out ideas. All contributed to confusion.

Tingle summarises the media’s contribution to confusion in a post on the ABC website:

The willingness of some sections of the media to perpetuate misinformation, and of other sections of the media to get lost in attempts at false balance, has made nigh on impossible a reasonably rational debate about what a permanent advisory body to the parliament and executive, whose actual remit would be defined and controlled by the parliament, might mean both symbolically and practically to Indigenous Australians.

Once again, it seems our leaders and newspapers "are not brainy enough or honest enough to try to teach Australians what it means".

And this is not because those leaders didn’t know.

Then there were the opinion polls. When there is doubt about an issue, particularly an issue about which people are not strongly engaged, it is easy for people to seek to go with the flow. The polls had their own positive feedback mechanism, contributing to the “no” vote.

“It won’t make a real difference to the lives of ordinary Indigenous Australians”

That was one reason for voting “no” revealed in the Essential poll, given by 18 percent of respondents. It’s the opposite to the extremes of the scare campaign.

Logically one may reason that if it’s harmless, we may as well give it a go, but people are probably concerned about the possible emergence of another bureaucratic institution (without considering the already heavily bureaucratized nature of indigenous policy).

And there are people, epitomized by the strong statements made by Lidia Thorpe from time to time, who asserted that those seeking reconciliation should reject this mere token of reform. An “all or nothing” stance is often taken by reformist movements who reject the idea that reform in democracies generally occurs in incremental steps.

1. Would the ABC give airtime to someone who denies the laws of planetary motion, or who claims that 5G towers cause Covid-19?. ↩

2. That a Liberal Party frontbencher can be espousing such an idea shows how far the party has drifted from its foundations – and from the moral precepts by which most reasonable people are guided. ↩

Electoral consequences

The Voice proposal arose from a process that transcended partisan politics. It could have stayed that way, but the leaders of the Coalition parties decided to take a “no” position and to frame it as an Albanese proposal.

The Coalition went on to accuse the government of being obsessed with the Voice, to the exclusion of other matters (as if a government cannot handle many issues at once), but it’s been the Coalition that still cannot let the matter go. Maybe that’s because it knows that the political debate will come back to areas where the Coalition’s weaknesses are exposed, particularly economic management and border protection.

The message from Dutton, and from his backers in the Murdoch media, is that the referendum’s defeat is a rout for the Albanese government.

The ABC’s Antony Green has a post simulating the referendum as a two-party contest, “yes” for Labor and “no” for the Coalition, revealing that if that were the contest Labor would be left holding just a few inner-city seats. As Green warns however, drawing on the history of Australian referenda, none of the outcomes in his simulation can be used as a predictive tool for the next election. A “no” vote in the referendum does not change the status quo, and it doesn’t bring on the risk of our waking up on Sunday morning to find a Coalition government has been elected.

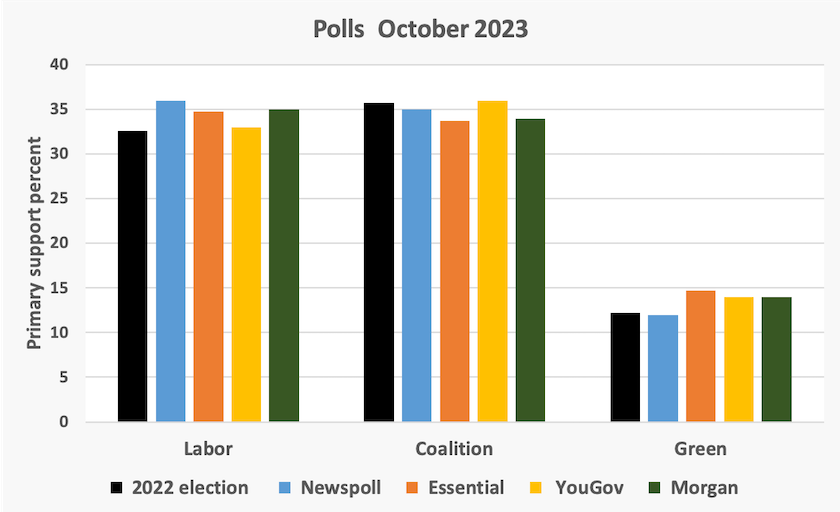

In fact, the day after the vote, Newspoll reported a 45:46 TPP lead for Labor, up a little from the previous poll, and it showed a sustained lead for Albanese as preferred prime minister.

Dutton’s strategy in this campaign was not about the Voice. Rather, it was about a desire to inflict damage on Labor by defeating a proposal to which Albanese was strongly committed. If there was a setback to reconciliation, and damage to Australia’s reputation, these were to be minor collateral costs for the greater benefit of damaging a Labor government.[3]

That strategy, while it might have worked in a previous era, hasn’t worked.

There was a time when the two main parties between them commanded more than 90 percent of the vote. What hurt one party was to the benefit of the other, but it is now almost 40 years since the Labor plus Coalition vote reached 90 percent (91.9 percent in 1987). Australian politics is no longer a zero-sum activity. The latest polls show that whatever movement there has been since the election has not been to the Coalition’s advantage.

Steve Bishop, writing in Independent Australia, stated that a failure of the referendum would be a pyrrhic victory for Dutton. Laura Tingle, writing immediately after the vote, notes that the trend doesn’t bode well for the Coalition. She reports:

Despite the comprehensive loss of the referendum, voters were repeatedly telling focus groups that they mark Peter Dutton down for the way he has conducted himself.

That is not to say the approach taken by Dutton and his “no” colleagues has been inconsequential. On the 730 program, commenting on Dutton’s political strategy, Tingle said that Dutton’s approach of sowing fear and confusion “will fire up conservatives to think this is the way you run politics”. (Her session is near the end, at 25:30.)

Nikki Savva, who knows the Liberal Party from the inside, has an article in the Age and Sydney Morning Herald If you thought the Voice was bad, just wait until the next election. Referring to Dutton’s “predilection for inflammatory language” and the brutal campaign waged by Advance Australia, she writes:

It [Advance Australia] was reckless with the truth, with little or no regard for social cohesion. The most damaging aspect was the black on black conflict. It was ever thus. It was lethal.

In the aftermath, Peter Dutton has shown scant remorse for the harm that might have been inflicted on Indigenous people or on the body politic by the lies and the racist themes by some No supporters. On Saturday night, Dutton declared it a “good day for Australia” and anyway, whatever harm was inflicted was not his fault, it was Albanese’s. In the fine tradition of former prime minister Tony Abbott – a key figure in Advance Australia – he kept his foot on his opponent’s throat.

Paul Stranglo of Monash University, writing in The Conversation, identifies the way Dutton is re-positioning the Liberal Party. He writes:

His calculation is that by taking ground in the outer suburbs, combined with holding seats in regional and rural areas, he will be able to forge a winning majority, a conservative coalition of support whose defining features are economic and cultural insecurity.

The parallels with constituencies that supported Brexit and Trumpism overseas are self-evident. Dutton’s strategy is a gamble but, as the results of the referendum show, it is not without rationale.

He describes Dutton’s approach to politics:

His is a hard-man leadership, devoid of nuance. In his world, vulnerability is weakness, and fear is a prime driver. He unambiguously taps a sense of grievance and, as often demonstrated during the referendum campaign, is unafraid to be an agent of misinformation (which is then amplified through the noxious channels of social media). Dutton is, in short, the local incarnation of a right-wing strongman populist.

The warnings by Savva and Stranglo are apt. Labor was caught off guard by the “no” campaign. Carol Johnson of the University of Adelaide, writing in The Conversation, suggests that Labor lacks a strategy for countering right-wing populism. Like Trump, Dutton and his colleagues were able to portray the Voice as a proposal developed by the “elites” against the interests of ordinary Australians which would run counter to our notion of fairness. (Savva describes Advance Australia as an organization “founded, funded and supported by elites supposedly to fight elites but in fact benefitting them by preserving the status quo”.)

Maybe Labor need not worry too much for now. Dutton’s approach won’t help the Coalition reclaim urban seats. They may make some inroads in outer suburban seats, where Labor’s margins were eroded at the election. But as pointed out in the ANU Australian Election Study, demography and dissatisfaction with the Coalition’s platform are working against them.

If Labor holds to its commitment to hold a referendum, Dutton, who is fiercely loyal to the British monarchy, would surely use the same strategy as he has used in the Voice.

The most serious issue is that over the long term politics has become less about ideas and policies. Dutton has taken political discourse to a contest based purely on demagoguery, where lies, logical fallacies, false information and fear campaigns have been the currency of politics.

Politics has always been dirty, but in his decision to avoid any argument about the merits or otherwise about the Voice, and to muster the support of the extreme right and conspiracy theorists, Dutton has taken a further step in that direction.

As much as this is a challenge for Labor, it is also a challenge for everyone whose politics are on the centre-right and who may be seeking to find a party with a realistic policy platform, guided by commitment to the truth and to uphold the institutions and conventions of democracy.

3. In spite of the attention commanded by the events in Israel, global media has given prominence to the outcome, generally in terms that are unflattering to Australia, as reported in The Conversation by Rebecca Strating and Andrea Carson of La Trobe University: “Lies fuel racism”: how the global media covered Australia’s Voice to Parliament referendum. ↩