Education

NAPLAN’s revelations – we’re heading for an education class divide

The NAPLAN national results were published on Wednesday. The NAPLAN website has links to a “commentary”, which is actually a short summary, of results from students in Years 3, 5, 7 and 9. That confirms most of what is already well-known: girls are more proficient than boys in reading, writing and grammar, but are behind boys in numeracy, and there is a big gap between indigenous and non-indigenous children.

The website also has a link to an Excel workbook, with a large amount of data disaggregated by state, gender, language background, parents’ education, and indigeneity – enough to occupy a quant for hours building pivot tables and speculating on causal factors.

Some teachers have concerns about NAPLAN, suggesting that it misses some important skills while over-emphasizing others. There is no one way to interpret its findings. Jessica Holloway of Australian Catholic University, writing in The Conversation, warns that because of changes in NAPLAN classifications we should be careful in comparing these results with earlier ones. But few would disagree with NAPLAN’s general finding that our school education system is performing considerably below what we would consider to be adequate standards, and whatever its bias, that it reveals indisputable disparities between different school students’ performance and opportunities.

A quick look at the Excel workbook confirms the gaps identified in the “commentary”. Unsurprisingly children with a non-English background are a little behind those with a native English-speaking background, but they are well ahead on numeracy. Also the difference in NAPLAN results between children whose parents hold a bachelor’s degree or higher and those whose highest education is Year 11 or below is stark. Both of these disparities have implications for social mobility. It is not hard to imagine the development of a concentration of poorly-educated “white” Australians who feel they have been left behind by an educated multicultural elite, and who turn to the populist politics of the far right.

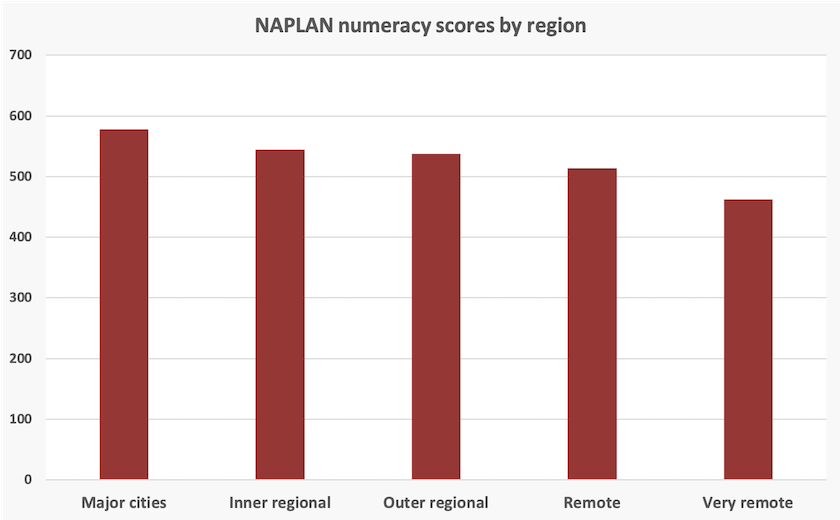

The spreadsheet also has a wealth of regional data. In numeracy, for example, there is no significant difference between New South Wales, Victoria and the ACT. Other states, particularly Tasmania, have lower scores, and the Northern Territory is a long way behind, largely explained by the gap between the scores of indigenous and non-indigenous children. (It is interesting to speculate on the differences that would be manifest if NAPLAN had categories for plant identification and land management, for example.) But indigeneity cannot explain away all regional differences. The graph below shows the NAPLAN numeracy scores for the five regional classifications, moving out from our large cities. (Reading and writing skills reveal similar but less steep differences.) It is not hard to imagine the development of a rural underclass – as has happened in many countries – ripe for right-wing opportunists to gain their support.

The government’s response to NAPLAN

On the ABC’s Breakfast program, Education Minister Jason Clare discusses his response to the NAPLAN results: Why are Australian school students struggling?. (13 minutes) The NAPLAN results confirm that our school education system needs serious and urgent policy attention. In part that is about funding: public schools are still at a funding disadvantage compared with private schools, and are not on track to reach the funding standards identified by the Gonski review. Clare is particularly concerned to bring in measures that can help students who fall behind in early years to catch up, because without special attention, such as extra tutoring, almost all of those who are behind in early primary school will also be behind in high school. He is concerned by the fall off in high school completion: six years ago 83 percent of students in government schools finished high school; now only 76 percent finish. That will not improve unless we help those who are already struggling in their early years.

In his interview Clare refers to the Government’s various programs to improve school and university education. He frames the need in terms of hard-headed economics: there aren’t many employment opportunities for those who haven’t gone on from high school to get a TAFE or university education. There is a large opportunity cost in leaving a proportion of the population under-educated.

Clare presents a strong economic case, but for the government to succeed politically with its education reforms there must be two attitudinal shifts. One is about accepting the need to pay more tax to fund education. The other is to see publicly-funded education not only in terms of distributive welfare – a basic system for those who cannot afford private schools – but also as a basic universal need for a well-functioning economy. From Howard through to Morrison, a war on learning was an essential aspect of Coalition governments’ “small government” policy.