Economics

The Intergenerational Report – “we can own the future”

Because the government trickled out pieces of the Intergenerational Report (the IGR) over a whole week, there was little of surprise when the consolidated report was released on Thursday.

This approach in itself is worthy of comment, because journalists had privileged access – days of privileged access, rather than the few hours normally provided under embargoes. That means the public have been subject to a bias – not the well-known “left/right” biases associated with different media, but the general bias of journalism. Journalism is a profession, and like all professions it has established methods, and its practices are partly shaped by Journalism academic streams in universities. That is not to criticise journalists’ approach, but journalists do have their own ways of looking at the world. The ABC’s Gareth Hutchens touches on this professional milieu in his essay What is the point of economic journalism?, which is about the ways journalists mediate between economists and the public. It would have been more in the spirit of open government had Treasury made those progressive releases available to all on its website.

To return to the IGR itself, it covers some of the same ground as previous ones, with its demographic messages about the economic and fiscal demands generated by an ageing population. Coalition governments were inclined to use the IGR fiscal projections as an argument for reining in government programs, or for shifting government programs to the private sector.

This IGR is refreshingly broader than previous ones, in that its emphasis is more on economics, particularly economic structure, than on mere fiscal issues. It deals with five forces shaping the Australian economy:

Climate change and the net zero transformation – presenting challenges and growth opportunities in green energy and critical minerals.

Population ageing – with associated demands on health and aged care services, but also with implications for superannuation. Notably, because of superannuation, Australia will be in the almost unique situation of being able to reduce spending on age pensions while its population ages.

Rising demand for care and support services – related in part to the ageing population, but mainly as a source of productive employment, rather than being seen as a burdensome overhead.

Technological and digital transformation – as an ongoing source of productivity improvement and in terms of new opportunities, particularly in relation to robotics and artificial intelligence.

Geopolitical risk and fragmentation – in a world where the rules-based order is weaker than it has been for decades, and where security of supply chains is more important than it was in a more open trading system.

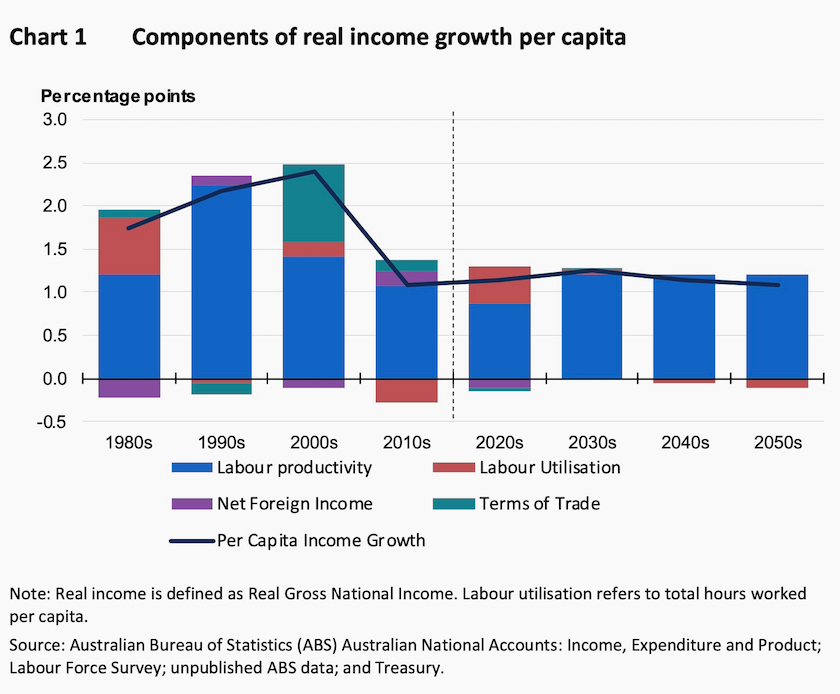

The IGR presents its faith in our ability to meet these challenges in terms of improved productivity. We may never again enjoy the productivity boost of the Hawke-Keating era, but we can do better than we are presently doing. A history and projection of our sources of income growth is presented in the report’s first graphic, copied below. Note particularly the blue columns, and the big aqua-coloured boost to our terms of trade in the 2000s: the Howard government had it lucky.

The IGR itself is a densely-packed document but you can gain a strong impression of the way the government is using it as an input to its economic policies in Treasurer Chalmers’ speech to the Press Club. It’s a particularly upbeat presentation, particularly for a treasurer. He repeats his theme “we can own the future” – a cliché perhaps, but it’s a hint that previous governments have tended to drift without taking responsibility for shaping our economic structure, and in terms of dealing with climate change it’s a reminder that previous governments have been neglectful. Otherwise, apart from a quip about Angus Taylor, Chalmers’ presentation is free of party politics. In fact he heaps praise on Peter Costello, the treasurer who initiated the IGR process and brought demography to our attention as an economic challenge. Chalmers comes across as the very model of a Treasurer, who as guardian of the nation’s treasure rises a little above partisan politics.

While Chalmer’s rhetoric is upbeat, when it comes to specific policy plans he defends the government’s incremental approach of small tweaks, such as its piddling changes to taxation of high-balance superannuation retirement accounts. It’s as if the challenges of an ageing population and climate change are 1000 years in the future, rather than serious problems here and now.

In the Press Club Q&A session journalists pressed him on taxation. Surely, if there is going to be such a load on our already-struggling public services, if revenue from fuel excise and tobacco are bound to decrease, and if effective competition policy brings corporate profits back down, some taxes must increase to compensate (GST perhaps) and overall taxes must increase.

Chalmers effectively evaded these questions, pointing to a projection in the report (page xv) that Commonwealth taxes should stabilize at 24.4 percent of GDP over the long term.

That’s hard to believe: 24.4 percent is only a shade above the 23.9 percent in this year’s budget estimates.

In fact the reasonable inference from the IGR is that if we are to sustain our present standard of government services, taxes will have to rise. We may not welcome higher taxes, but they are surely far better than a miserable future of low-tax austerity, a future of emaciated public services and expensive private services.

It’s simple to calculate the cost of higher taxes on our disposable income. People’s awareness of that obvious cost invigorates the anti-tax movement.

It’s harder to calculate the cost of scaling back government programs and shifting resources to the private sector. The cost of scaling back services is in what isn’t delivered – the roads and subway systems that aren’t built, the publicly supported arts, entertainment and public broadcasting that we don’t get a chance to enjoy, the payments that would allow the unemployed and the disabled to live dignified lives rather than to beg on the streets.

The costs of privatizing functions that should more properly be provided by the government is more visible: road tolls, private health insurance, private school fees, all costing more, and generally delivering more inequitable outcomes, than the same services provided by governments. For every $1.00 we save in taxes we have to pay more for the same services provided by private operators.

That’s not a case for nationalizing everything: rather it’s a case for having the government sector, the corporate sector and the community sector, all do what they do best.

Arguably (as Miriam Lyons and I, and as many others point out) we are trying to get by with too small a public sector now. But why does the public sector, and therefore our taxes, have to grow over the long term?

There are basically two reasons why public expenditure, and therefore taxes should rise, and they are both acknowledged in the IGR.

One reason is an ageing population, which itself has two roots. We are living longer and having fewer babies. And as the IGR makes clear, we cannot keep our population young forever through immigration. Arguments about “dependency ratios”, are overstated. These arguments are about a proportionately smaller workforce supporting a proportionately larger idle and ill number of retirees. Unless we’re French we can push up the retirement age as people enjoy longer years of good health. But there is still some validity in the mathematics of the dependency ratio.

The other reason is in the nature of what is produced in the private and public sectors. Much of the stuff we get from the private sector has been subject to extraordinary productivity improvements over a long period. Think of the prices of your parents’ or grandparents’ cars, washing machines, television sets and clothes, compared with much more affordable alternatives now. Most of that productivity improvement has been in terms of substituting labour with capital. Many public services, however, are intrinsically labour intensive. Think of teaching, nursing, policing, care of the aged. Of course these services can and do benefit from application of new technologies, but not to the extent that has occurred in manufacturing. Also, for the most part, they have to be delivered locally. Apart from a few exceptions such as dental tourism, we cannot import these services from countries where labour costs are lower. This phenomenon is known as the Baumol effect: there’s a short explanation on National Public Radio and a longer explanation incorporating economists’ beloved curves in Marginal Revolution.

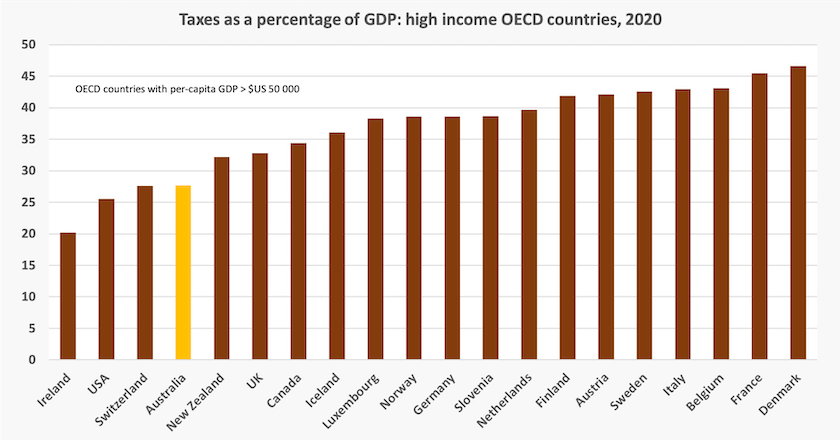

Contrary to much popular opinion revealed in Per Capita’s regular tax surveys, contrary to the Coalition’s “small government” propaganda, and challenging the IGR’s 24.4 percent of GDP cap, Australia is a low-tax country. Where we stand in comparison with other high-income “developed” countries is shown in the diagram below (which includes Commonwealth, state and local government taxes). Two countries ranking below us – Switzerland and Ireland – operate in part as tax havens (Ireland’s “Leprechaun economy” is sui generis), and the third, the USA, keeps its taxes low by running up huge budget deficits, financed by the rest of the world.

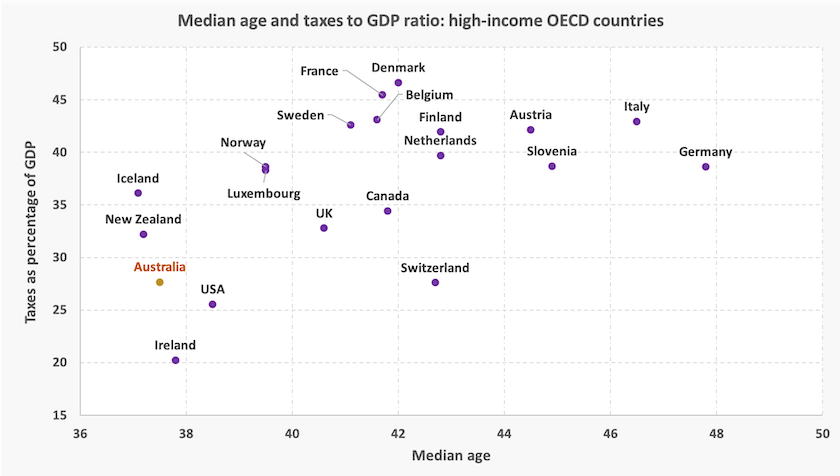

It is also revealing to look at the extent to which taxation is related to the age structure of these same countries. This is shown as a scatter diagram. Countries with an older population tend to be countries with high taxes, as is revealed in the top right-hand corner of the diagram.

That doesn’t mean we should simply increase the rates of tax across the board. We have interrelated systems of taxation, superannuation and transfer payments that privilege classes of older Australians, while leaving responsibility for paying taxes up to younger, working-age people. Unless this imbalance is rectified, through measures such as bringing so-called “self-funded” retirees into the same income tax system as wage earners, replacing state government stamp duties with property taxes, and finding other wealth taxes, the imbalance will worsen.

It also means we need to change our thinking about taxes – to shift from thinking about the “burden” of taxes, to thinking of taxes as the price we pay for civilization, as Oliver Wendell Holmes put it. Just as we don’t refer to the “burden” of paying for a new car or a meal out, we shouldn’t have to think of paying for Medicare, safe roads, or the protection provided by the police force and our armed forces, as “burdens”. These are all part of what we share, the common wealth that holds our society together.

That thinking was absent from Treasurer Chalmers’ speech, however.

Ken Henry on intergenerational responsibilities

Politicians and journalists often talk about “the environment” and “the economy” as if they are different domains, but such a division is meaningless, and it leads to bad public policy. They are both about the allocation and care of scarce resources, and they both involve comparing present and future values. The idea of some trade-off between “the environment” and “the economy” is a false dichotomy.

Former Treasury Secretary Ken Henry, author of the 2010 Australia’s Future Tax System Review, does not believe in any environment vs economy trade-off. He was on ABC Breakfast talking about public policy regarding the future – the New South Wales government’s failure to maintain the diversity and quality of ecosystems, including their doubtful capacity to adjust to climate change, and the Commonwealth government’s Intergenerational Report: “An intergenerational tragedy”.

On the IGR he stresses that we are not acting fast enough in dealing with climate change. The Albanese government is trying to catch up on the years of Coalition neglect, but it is working “with instruments that are really not up to the task”. It is huddled in a corner, “too afraid to do anything sensible to address the mighty changes we need”.

He is not afraid to state that we have to increase taxes and change the way we collect taxes. He stresses that reliance on personal income tax (the IGR projects even heavier reliance on personal income tax in the future) is an intergenerational inequity, because it is collected from people in the workforce, already dealing with education debt and unaffordable housing, rather than retirees and others living off asset returns.

He advocates a lower company tax. He acknowledges the function of dividend imputation: it makes for a low tax on domestic investors, while it comparatively penalizes foreign investors, who pay the full 30 percent tax. He acknowledges that it is de facto a way to collect taxes from mining companies, but specific taxes on the mining sector would be a better way to achieve that objective.

It’s unfortunate that this discussion ran out of time, because it’s one of the few times the ABC has had a well-informed discussion on company tax and imputation. Ken Henry is right in pointing out that our imputation system relatively favours domestic investors over foreign investors, but do we need a big inflow of foreign investment? We were once highly reliant on foreign investment, but largely because of superannuation, we are now net overseas investors ourselves. Also imputation, in encouraging companies to pay dividends, rather than re-investing and growing in market power, helps to re-distribute surpluses. In aiding a reallocation of corporate profits it complements competition policy. Ken Henry would surely have addressed these questions had the interview been longer.

Improving productivity and a fairer housing market should underpin tax reform

The Intergenerational Report has raised the question of tax reform – a subject that neither of the two large parties has wanted to run up the flagpole.

Independent MP Allegra Spender broaches the subject, however, in an ABC Breakfast interview: Our tax system isn't set up for the future.

She has two main messages.

The first is that if we are to raise more revenue without seeing people’s disposable incomes reduced, we need to lift productivity. That’s pretty well straight arithmetic.

If productivity doesn’t rise, any increase in taxes has to be offset by a cut in disposable income. But if productivity does rise, we can devote a large share of that growth in productivity to funding necessary public expenditures identified in the Intergenerational Report. We can increase our tax-to-GDP ratio, presently one of the “developed” world’s lowest, without reducing people’s disposable income.

Spender doesn’t take us through that arithmetic, probably because she knows if she were to state explicitly that we need to collect more tax it would be a red rag to the “small government” mob. She leaves us to work out the arithmetic.

Her other message is about rectifying some of the huge inequalities in our present tax arrangements, which place most responsibility for paying tax on young people of working age, while leaving older people lightly taxed – a situation that will become less sustainable as our population ages. (It isn’t really sustainable now.) A related intergenerational inequity is in housing, for which she sees the need for more supply to make housing more affordable.

She also mentions the problem of a shrinking GST base, because of exemptions.

That’s probably about as far as any politician can go in advocating tax reform, without bringing down a barrage of fire from right-wing media, and getting hammered by journalists with their “can you rule out X?” questions (where X is a higher GST, the end of negative gearing, and so on), or with assertions that our taxes are high and must be reduced. The ABC’s Sarah Ferguson provided an example of such questioning on Wednesday night’s 730 Report when she repeatedly asked Treasurer Chalmers if he intended to lower the company tax rate. She asserted that our company tax rate is 30 percent, one of the world’s highest, clearly not understanding that our dividend imputation system results in the actual corporate tax rate paid by Australian investors being among the world’s lowest.

The points Spender make, made by Ken Henry and by many others before, are that a change in any one tax can adversely affect some groups, but comprehensive tax reform can deliver offsetting benefits for those adversely affected by particular tax changes, and a set of tax reforms that lift productivity can benefit everyone.

The BCA plan for Australia

Coinciding with the release of the Intergenerational Report the Business Council of Australia has used the occasion to advocate for comprehensive economic reform, in its report Seize the moment: a plan to secure Australia’s economic future. In many ways it urges the government to get on with its agenda on decarbonizing the economy, investing in skills, and advancing the economic interests of women. It’s a move-on prod to the government to pull the economy out of its structural slump and to diversify our productive base.

The link above takes one to a press release, which has onward links to a summary and the full report. If you have 8 minutes to spare you can hear the BCA’s Jennifer Westacott explaining its context, and the urgency of economic reform on the ABC.

On taxes the BCA report explicitly states that our tax system “will not raise enough revenue for the goods and services the community needs and expects”. That’s hardly radical, but it’s not what we generally hear from business lobby groups.

The BCA wants the taxes we presently collect, and may collect in the future, directed to ways to improve productivity.

It calls for a broader and higher GST. That would be a brave call for any politician, and we can expect a chorus of opposition from the “left”, because the GST is a regressive tax, particularly if it is expanded to cover food and other items presently exempt.

Such a reaction, however, is too impulsive, because in any proposal for tax reform we have to consider the way revenue from taxes is spent.

Under our revenue-sharing arrangements, the GST, although collected by the Commonwealth, goes to states, and state expenditure on schools and hospitals (accounting for about half of state governments’ recurrent outlays) is highly progressive in its distribution. They are also areas of greatest need in the long term, as revealed in the Intergenerational Report and the latest NAPLAN results. Another aspect of the GST is that unlike income tax, the privileged and pampered rich can hardly avoid it. The Nordic countries – Norway, Denmark and Sweden – often held up by the “left” as models of progressive government, all have VAT taxes of 25 percent, compared with our 10 percent GST.

The BCA also calls for a reform of capital gains taxation, to tax the “real gains”. That’s a reminder, again to those on the “left”, that the changes introduced by the Howard government in 1999 were more complex than halving the base of CGT. They also abolished indexation. These changes were highly favourable to stock market or housing speculators, but in taxing illusory gains in asset values resulting from inflation, they actually penalized long-term patient investors. It would be a bit much to find the BCA explicitly pointing out that the Howard government discouraged business investment while encouraging speculators, but that’s one of the many ways the Coalition mismanaged the economy.

The BCA calls for reforms of state taxes, but apart from a higher GST it really has no other plan to increase public revenue.

It actually calls for a reduction in our company tax rate, citing the 30 percent headline figure, without acknowledging that because of imputation the tax on Australian investors in public companies is actually around 15 percent (the actual rate depending on the level of dividend payout), which is very competitive by world standards.

It supports the Stage 3 tax cuts, cuts that will mean more to executives than to the real owners of corporations – the millions of Australians who hold equity through their superannuation funds. (Marx would be intrigued to learn of a business lobby standing up for workers at the expense of owners.) And the BCA asserts that more infrastructure should be privately-funded, even as we learn of the economic costs of mechanisms such as toll roads. There is a large gap between government bond rates and the profits expected by private investors. We’re paying a huge opportunity cost in terms of inadequate infrastructure, in holding back on public infrastructure funding.

The cost-of-living “crisis” explained

We know that people who have large mortgages, particularly mortgages that have reset from short-term low-interest fixed rates, are doing it tough. More widespread are reports of shock at the supermarket checkout, while at the same time many people, including well-off older people, are asking “what crisis?”.

Writing in The Conversation John Hawkins of the University of Canberra explains how economists, concerned with guiding public policy, try to get some measures on the cost-of-living: You don’t have to be an economist to know Australia is in a cost of living crisis. What are the signs and what needs to change?

Along the way he explains how the Consumer Price Index – the most commonly-used indicator of inflation – is constructed, and why different people experience inflation differently. What stands out about our post-Covid inflation is that living costs for workers (“employee” households) have risen much more than the CPI and have also risen more than for other groups, including self-funded retirees.

If you want a full explanation of inflation, of the way the Reserve Bank interprets it, and how the CPI relates to what’s happening in supermarkets, at gasoline pumps, and in our bank balances, there’s a paper inflation explained.

More sensible talk on housing policy

Expect more high-rise in future developments

When an interjector at a town hall election rally asked Prime Minister Menzies “Wotcha gonna to do bout ousing?”, his arrogant response was that he would put an “h” in front of it. But at least the Menzies government, and largely conservative state governments in the 1950s and 1960s, sustained an ambitious program of public housing. It wasn’t called “social housing” in those days, whatever that adjective means.

We need to return to an ambitious public housing program, John Hewson points out, in his Saturday Paper contribution: Markets have failed on housing. He reminds us that for all the noise about their programs and proposals, the Commonwealth government’s allocations for public housing are miserable:

The elephant in the room is that all these incentives are still prospective and they’re not as big as they look – the $3 billion translates to only about $15,000 per home and won’t be paid until at least 2028.

The market failure to which he refers is the behaviour of property developers, who have a strong incentive to keep house values high, and through “land banking” (holding back land from development) have the means to sustain high prices in the same way as other monopolists and oligopolists hold back supply in order to sustain high prices.

In what would be considered a heresy if he were still a prominent member of the Liberal Party, he calls on governments, particularly state governments, not just to release and re-zone land for housing, but to be more active in urban planning, so that along with houses and roads, there are facilities that help develop communities – “shops, TAFEs and parks”.

Another measured voice on housing is in a 10-minute ABC Breakfast segment “There are no quick fixes” for the housing crisis, where Susan Lloyd-Hurwitz of the National Housing Supply and Affordability Council is interviewed. She covers a great deal of ground – the federal, state and local economic issues in housing, the need for policies to support a build-to-rent housing industry, and above all the general requirement for policies directed to the supply side of housing.

She adds her voice to opposition to rent controls – a policy proposal with few friends among economists be they of “left” or “right” inclination. But as the latest Essential poll reveals, a rent freeze has strong appeal to young people, Labor and Green voters, and (unsurprisingly) to renters. In holding out on rent controls the Greens are following the populist path of the Liberal and National parties – grabbing on to an economically dumb but superficially attractive proposition.

Ross Gittins explains the political economy of housing in his post Why Albanese’s housing solution will help, but only a bit. He points out that until now the main political issue of housing has been around affordability for first-home buyers, but now the focus is on the problems of renters, and the Greens have moved into that space.

He also suggests that at last the housing debate has shifted to the supply side: we shouldn’t expect to see any more demand-side policies, such as grants for first-home buyers. He also explains what the government and advocates such as Susan Lloyd-Hurwitz mean by “well located” housing. It’s about more dense and high-rise housing in suburbs that have so far resisted densification. We can expect to see a lot more NIMBY politics in the near future.

Missing from the housing debate, however, is any questioning of the assumption that the solution is primarily in terms of stuffing more people into our existing large conurbations. In terms of its settlement pattern Australia is a strange country, with 16 million of our 26 million population in five large cities. Perhaps the Labor Party is haunted by memories of the Whitlam government’s DURD experience (Department of Urban and Regional Development). DURD had wondrous ideas about new and expanded settlements but because it was hostile to building transport infrastructure to link them up it was a monumental disaster.