Politics

Dutton’s gamble with the Liberal Party

In a Conversation contribution – Accentuate the negative: why the Liberal Party’s fondness for ‘no’ might ultimately backfire – Marija Taflaga of ANU explains why the Opposition has deliberately decided to mount hysterically negative attacks on every government proposal – particularly the Voice referendum – while offering no policies of its own.

Dutton hopes that failure of the Voice would damage Albanese’s standing, and that voters would then come back to the Coalition.

She explains that Dutton’s logic rests on three assumptions:

- that the prime minister, and not the opposition, would be blamed for the yes campaign’s failure;

- that Labor will oblige the opposition by tearing itself apart;

- that politics is zero-sum and every vote lost from Labor is one for the Coalition.

She questions all three assumptions, particularly the third.

On the second assumption, if the Labor party is to tear itself apart it has a chance to do so at the National Conference currently in train, but that is unlikely. There are policy differences – as there should be in any democratically-organized party – but there is no sign of a rift.

And on the first assumption, Dutton with help from Pauline Hanson and the Murdoch media is making sure that a failure of the referendom, if it occurs, will be sheeted home to Dutton. He had a chance to mount a considered and rational case against the voice, distancing himself and the Liberal Party from peddlers of misinformation and racists, but he chose not to take that path.

A conservative on the Voice

From 1990 to 1994 John Hewson was Opposition Leader – the position Peter Dutton now holds. According to Wikipedia he let his membership of the Liberal party lapse, but he still describes himself as a “conservative’.

Two quotes from his Saturday Paper contribution – Mixed Voice messages – summarize a conservative’s case for the Voice:

The far right of the current Coalition and their complicit media mates risk doing irreparable damage to what should be in our national interest and a huge step forward for the country and all its people. We should all be able to take pride in our heritage, but we should all be aware of and acknowledge its full story. We must seek to eliminate any continuing unfairness in our system. This is to the benefit of all Australians.

And

This is not a test of Prime Minister Anthony Albanese but rather a test of all Australians – of who we are and who we want to be and how we hope the world will see us.

A world map of secularization and liberalism

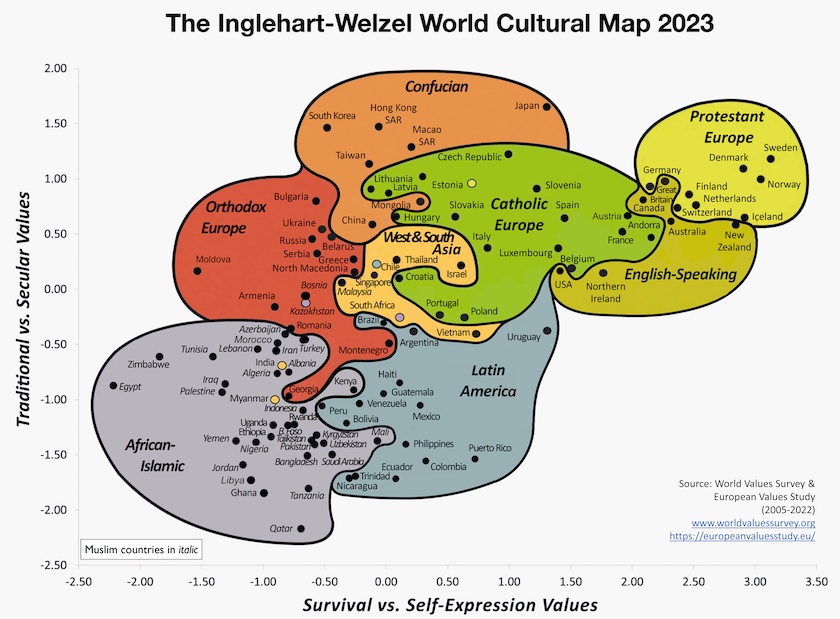

If you want to sound like a smart-aleck at a social gathering, ask people how they regard the 2023 update of the Inglehart-Welzel World Cultural Map 2023, produced as a part of the World Values Survey.

It is essentially a 2 X 2 scatter diagram, with a geographical overlay. Full descriptions of the variables are given on the website, but in simplified terms the vertical axis is an indication of secularization – the extent that a society has moved away from traditional family and religious codes – while the horizontal axis is the extent to which societies have become more open, trusting and tolerant (“Survival vs self-expression values”). Over this scatter diagram the authors have drawn a map of clusters of regions – a clever force-fit. We come into the “English-Speaking cluster.

If it’s hard to read, click on the button for a larger (2X) image ![]()

Some may be surprised that our nearest cultural neighbour is Switzerland – a country where women did not gain full voting rights until 1990 and where some cantons have fallen short in tolerating religious pluralism. Notably Britain, in spite of having an established church, shows up as more secular than Australia. But the pattern seems to align with general perceptions.

The authors suggest that as countries develop they tend to move towards the top right. To demonstrate that movement they have an animated map, showing how countries have moved from 1981 to 2015. Australia moves upwards in secularization, but we do not move across towards more openness and tolerance. Unsurprisingly the Nordic countries occupy the top right-hand corner, and the USA is down in the bottom left of the English-speaking cluster.

How authoritarian populists exploit incumbency

Hungary and Turkey are very different countries. One is predominately Catholic, the other is predominately Islamic. One is in the EU, the other is a long way from EU membership. One has been enjoying strong economic growth since the fall of European communism, the other has much lower income and an economy suffering high inflation.

Both, however, have populist-authoritarian governments that succeed in getting re-elected. Writing in Social Europe – How populists stay popular, from Ankara to Budapest – Stephen Pogány of the University of Warwick, UK, describe the techniques employed by Recep Viktor Orbán and Tayyip Erdoğan to strengthen their hold on power. Without the constraints imposed by of EU membership, Erdoğan has some more leeway than Orbán, but their techniques are broadly similar, mainly to do with controlling media, either directly or through doing deals with sympathetic media owners, suppressing opposition parties, surrounding themselves with a chorus of cronies, and employing a suite of educational and cultural policies to reinforce the regime’s ideology.

Elections are an inconvenience to authoritarian strongmen, but with enough control of the media, a muzzled opposition, and some old-fashioned work on boundaries and franchises, authoritarian populists can turn elections to their advantage because through providing a semblance of “democracy” elections legitimize their regimes.