Health

Private health insurance – subsidies by stealth

A Conversation article by Yuting Zhang of the University of Melbourne and Nathan Kettlewell of UTS, Sydney, alerted me to a review of subsidies to private health insurance, conducted by the Department of Aged Care.

Reference to the review is on the Department website: Consultation on the Private Health Insurance (PHI) Incentives and Hospital Default Benefits Studies. The review was started on June 6 and was closed for consultation on August 15.

It is weird.

I had heard nothing about it, but knowing I might be out of touch I got in contact with two people heavily involved in health economics, and they hadn’t heard anything about it either.

Governments of all persuasions have reviewed aspects of PHI arrangements from time-to-time, but they have given plenty of publicity to these reviews. The Productivity Commission is the usual body tasked with conducting reviews about industry subsidies, and the Commission takes great care to see that there all views are canvassed – the industries concerned, consumers, and researchers.

What lies behind the stealth in this review?

If you follow the link &ldquoå;Give us your views” – on the Department’s website, you eventually get to a “consultation paper”, which refers to reviews by Finity Consulting and Ernst and Young (EY). It states that:

Independent studies were announced in the 2020-21 and 2021-22 Budgets and covered the following:

The effectiveness of the regulatory settings for the Medicare Levy Surcharge (MLS), Rebate, and Lifetime Health Cover (LHC) (collectively referred to as the PHI Incentives); and

Hospital Default Benefits.

Maybe there was reference somewhere in the thousands of pages of budget papers, but to say there were “announced"’ is misleading.

Why has the Albanese government, ostensibly committed to using the public service (such as the Productivity Commission) to analyse and advise on policy, continued with a process established by the previous Coalition government, presumably to justify yet more assistance to the pampered and high-cost private health insurers?

To see what is proposed, you can follow links in the consultation paper until you land on a paper by Finity Consulting titled “Risk equalisation: final report”, with the subtitle “Department of Health and Aged Care”. Does that subtitle mean it’s endorsed by the Department?

The Finity Consulting paper suggests ways the government can enhance the incentives for people to take up PHI. It is aimed at people who rationally choose not to take PHI, or take minimum PHI cover in order to avoid the Medicare Levy Surcharge. That is it’s about virtually forcing people into PHI, even though they assess they don’t need it.

There are two unquestioned assumptions in the exercise.

One is that it is desirable to increase membership of PHI and people’s use of private hospitals.

The other is that “risk-equalization”, whereby the fit and healthy subsidize those needing more intense health care, is best done through private health insurance, rather than through Medicare. This ignores the political acceptance of Medicare, the fact that Medicare is much more administratively efficient than PHI, the capacity of national insurers such as Medicare to contain providers’ costs (Medicare saves us from the horrors of America’s PHI-funded system), and the fundamental equity in using the tax system to spread risk and the burden of health care spending: trying to use private mechanisms to achieve equity in health care just doesn’t work.

A proper review would start with the question: is there any economic justification for supporting PHI?

Because there was a tight deadline, I dashed off some comments, reproduced below:

Four comments.

One is the use of a firm of consultants to undertake the research and advise on policies. Private health insurance is such a fiscally expensive intervention, with significant consequences in equity and distortion of resource allocation, that nothing short of a reference to the Productivity Commission, a body staffed by professional economists without commercial interests, should be undertaken. See the section “50 years without scrutiny” in my 2018 paper to the Australian Health Care Reform Alliance. (Another 5 years makes it 55 years.)

Second is the stealth with which this review has been undertaken. How were academics and others with an established track record in health financing to know of this work?

Third, is the premise that there is something economically virtuous in private health insurance. It is administratively expensive, it diverts resources away from public hospitals and contributes to health care price inflation, it subsidizes queue jumping, and it undermines support for Medicare. In all, it is a privatized tax, doing at high cost what a single tax-funded public insurer does at lower cost and with more equitable outcomes. See my 2016 paper Private Health Insurance and Public Policy to the Health Insurance Summit. (And on my website I have many more research and conference papers on PHI.)

Fourth is the set of recommendations by Finity. If one accepts the premise that people with higher incomes should be encouraged to take PHI and to use private hospitals, then their recommendations make logical sense within a narrow framework. They are grossly unfair, however, on two groups of people:

those civic-minded citizens who wish to support Medicare as a moral compact;

those who are well off and wish to pay for their own hospital care from their own resources, avoiding the moral hazard of PHI and its 15 - 18 percent administrative overhead. This group would be further disadvantaged by incentives to take “Silver” or top cover.

But more basically, the premise is wrong. Public policy should be directed to eliminating PHI as a high-cost industry, in the same way as other high-cost industries were phased out in the economic reforms of the 1980s.

To come back to the Conversation article, its message is in its title: Private health insurance is set for a shake-up. But asking people to pay more for policies they don’t want isn’t the answer. That’s a strong point – why should Australians be bludgeoned, essentially conscripted into buying a product they don’t need, and discouraged from sharing their health care needs through the taxation system, which is the case in almost all other civilized countries?

The authors go on to write “we recommend gradually reducing public support for private health insurance”. My only comment is that the word “gradually” should be cut, and the word “reducing” should be replaced by “eliminating”.

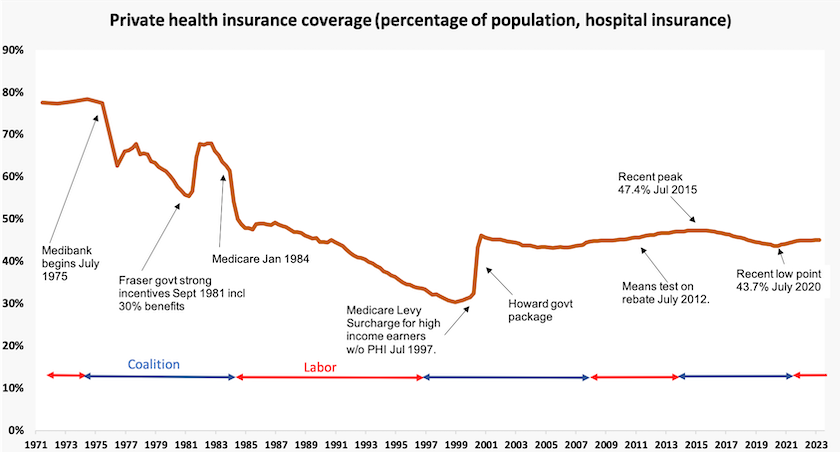

That’s because over the period 1983 to 1986 the government made good progress towards eliminating PHI, as shown in the graph below. But, as with an infection that has been inadequately combatted, this gradual approach failed: PHI was able to re-establish itself from that diminished base.

And to clarify matters, eliminating support for PHI does not mean eliminating support for private hospitals. There are many ways they can be integrated into the health care system without funding passing through a high-cost private financial intermediary.

The Commonwealth must kick in more for public hospitals

Public hospitals are stressed.

Under the National Healthcare Agreement – an agreement that makes the Treaty of Versailles look rational – the Commonwealth funds roughly 45 percent of the recurrent cost of public hospitals, while state governments pick up the balance of recurrent funding and all capital funding for public hospitals. (Most other government spending on health care is picked up by the Commonwealth.)

Martyn Goddard, writing in his Policy Post describes how public hospitals are overloaded, and calls for more contribution from the Commonwealth when the next iteration of the National Healthcare Agreement comes into effect in 2015. State and Commonwealth health departments would already be busily negotiating that agreement.

In his post – Labor has one last chance to save public hospitals. But will they? – Goddard puts the case for a stronger contribution from the Commonwealth to relieve pressure on public hospitals. It should contribute to capital funding for hospitals, fund alternative and lower-cost care for those occupying high-cost hospital beds but who don’t need acute care, and increase funding for primary health care, because a well-functioning primary health care system can keep people out of hospital.

As the previous article in this roundup points out, we can fund public hospitals at low cost and with equitable outcomes through our taxes, or at high cost through private health insurance, which is essentially a privatized tax. With its inherited “small government” obsession the Commonwealth may be tempted to push more of the funding load on to private insurance, but how do Australians benefit from being saved $X in taxes if they have to pay much more – probably $1.5X or $2.0X – for private health insurance to deliver a less equitable distribution of health care?[1]

1. Those factors – a private insurance premium of 50 or 100 percent over taxes – aren’t random guestimates. They come from comparing the national cost of single-payer health care systems, as in UK, Canada and the Nordic countries, with private insurance systems, as in the US. ↩

Poverty and poor health

It is well-known that poverty and poor health outcomes are correlated. When it comes to determining causal factors it is difficult to determine the extent to which poverty contributes to poor health or if poor health, particularly chronic disease, contributes to poverty.

Kadir Atalay and Rebecca Edwards of the University of Sydney, writing in The Conversation, report on their research on the relationship between cancer and poverty: Poor, middle-aged Australians are more likely to die from cancer – and the gap is widening. They find that middle-aged men living in Australia’s poorest areas (lowest 10 percent by SES disadvantage) are twice as likely to die of cancer as those living in the richest areas (top 10 percent). The ratio for women is 1.6 times.

That suggests there is some factor associated with poverty contributing to cancer deaths. (In the case of cancer, causality is unlikely to be in the other direction.) But the causal factors are hard to determine – diet, exposure to toxins etc? Drawing on spatial data to narrow down the causal relationship, they suggest unequal access to health care, particularly for screening, early diagnosis and treatment options, may play a strong role.

A more equitable distribution of GPs would help with screening and early diagnosis, but under present funding arrangements some poor non-metropolitan regions cannot support a GP. Peter Breadon of the Grattan Institute notes that the Commonwealth has developed means whereby clinics can make better use of allied health workers. But that initiative applies only where there are existing clinics. He suggests ways, requiring only a modest financial contribution from the Commonwealth, that would allow these under-served regions to establish clinics, by drawing on and pooling health care resources: How to get more GPs into rural areas.

Vale Mary-Louise McLaws

The Sydney Morning Herald has a short obituary to Mary Louise McLaws: Epidemiologist who led Australia through COVID dies aged 70. The ABC’s Virginia Trioli has a more thorough account of her life and her contribution to the public good.

Hers was a voice of reason at a period when reason was in short supply. True to her profession, she calmly explained the simple logic of viral reproduction – mathematical common sense backed by academic rigour – while politicians were pretending that there was some trade-off between health and “the economy”, while cranks were peddling weird theories, and while conspiracy theorists were spreading dangerous lies.

It is because her voice, and the voices of other independent epidemiologists, prevailed, that Australia came through the epidemic relatively lightly with 20 000 deaths, compared with the 100 000 deaths we would have experienced had we followed the example of other countries where independent experts like Mary-Louise McLaws were not heard.

Her contribution to our lives reminds us of the value of universities and other independent institutions, and of disinterested public broadcasting in connecting the public with their work.