Housing

The National Housing and Homelessness Plan

In committing itself to developing a National Housing and Homelessness Plan the government has set itself a huge challenge. It’s a challenge politically, most notably around the standoff with the Greens about the Housing Australia Future Fund, and around housing affordability generally – both for renters and buyers. It’s a challenge financially: the amounts at stake are listed in a press statement by Julie Collins, the Minister for Housing, and Minister for Homelessness.

And it’s a problem administratively for three reasons: first because problems in housing and homelessness merge into one another (e.g. homelessness and rental shortages are parts of one broader problem); second because most practical measures are in the hands of state and local government; third because many areas of public policy are involved – immigration, taxation (state and Commonwealth), public health, income support, indigenous affairs, and climate change (comfort and insurance costs) – to name a few. Public servants and ministers, Commonwealth and state, have to think beyond their own portfolios and budgets, and think about national financial and economic issues. That challenges the “New Public Management” culture, taken up by many government agencies, which discourages system-wide thinking.

The Department of Social Security has an inquiry underway, with an issues paper, accessible from its website, from which you can download a summary paper, or a longer (83 page) full paper. The summary paper covers most issues, but is light on background information. Some of that background, such as the shortage of rentals and the decline in availability of social housing is well-known, but some other situations and developments have not come to public attention. For example:

- almost half of people sleeping rough have mental health issues;

- people under 12 are the fastest-growing cohort of homelessness;

- for every one rough sleeper there are about 16 other homeless people couch surfing, sleeping in boarding houses or supported accommodation, or living in severely-crowded dwellings (39 percent of all the homeless);

- overcrowding is a significant issue in many indigenous communities, particularly in the Northern Territory and Queensland;

- the standard of social housing in terms of basic amenities has fallen significantly over the last seven years.

Submissions to the inquiry are open until Friday 22 September. The consultation papers have a number of questions to prompt responses: there are many specific questions in the full paper, and 7 broad questions in the summary paper.

For comparisons with other countries it’s informative to browse through the OECD Affordable Housing Database. The housing problems we experience are experienced in many other “developed” countries. In particular the idea that in comparison with other countries we have high home ownership, which was once the case, no longer holds.

Wise words on rent

Kos Samaras, whom we generally associate with his polling work in Redbridge, has written in the Saturday Paper about public policy towards renters.

The title Rent control is not the solution summarizes his article. As anyone who has looked at rent controls in the US can attest, rent controls slowly develop a slum system of poor property owners and poor tenants. The long-term solution has to involve supply, but there can be immediate policies to address tenants’ rights, particularly protection against eviction which is one of renters’ main anxieties.

His broader argument, which can be overlooked in discussions about the technicalities of no-grounds eviction, indexation of rents, rules on pets and pictures, and so on, is about the need to reform the whole culture of the rental market. A reformed market would have the same customer-supplier relationships that characterize other markets, rather than a medieval tenant-landlord (what a ghastly word!) relationship.

Renters in other countries, including most European countries, have a much better experience than renters in Australia, because in those countries renting, particularly long-term renting, is considered as an option that many will choose over ownership. He explains why it is different here:

In Australia, political parties have only ever been interested in Australians who bought into the “Australian dream”, taking advantage of the politics around the continuing aspiration for a secure future in which to build a life and raise a family while the value of their home grows.

A model for affordable build-to-rent

So far there are few build-to-rent projects in Australia, and those that have been built are mainly for the mid-to-top end of the market.

On the ABC’s Saturday Extra last weekend, Dan McKenna of Nightingale Housing described a small (54 dwelling) build-to-rent project in Marrickville: Affordable apartments on church land in Sydney.

Two aspects of the development stand out. One is the high quality of the architecture and the other is the attention to economizing without compromising comfort. For example, there will be a communal laundry, which not only saves building costs but also provides a shared facility that will help pull the community together. The funding model is also creative, having involved flexibility from investors, the local council, and the Churches of Christ who own the land. (12 minutes)

Geraldine Doogue urges listeners to visit the Nightingale Housing website to get a sense of the organization’s business model.

Are the worst of our housing problems behind us?

Have you heard about the “fixed rate cliff”?

It’s a term to describe a particular phenomenon in the Australian housing finance market, where buyers are able to take out mortgages at a fixed rate, but for a limited period. Many borrowers took advantage of fixed-rate offers in 2020 and 2021, when interest rates were low, and when they relied on the Reserve Bank’s assurance that interest rates would stay low until 2025. These mortgages are now coming to maturity, which means borrowers have to renegotiate their mortgages at higher rates.

Alan Kohler has a short video clip explaining why most mortgages in Australia are variable rate, or fixed only for a short period. It’s an accident of political history, a rare example of a US policy being more consumer-friendly than an Australian policy – or to re-frame it, as an Australian policy being friendlier to the finance sector than an American policy.

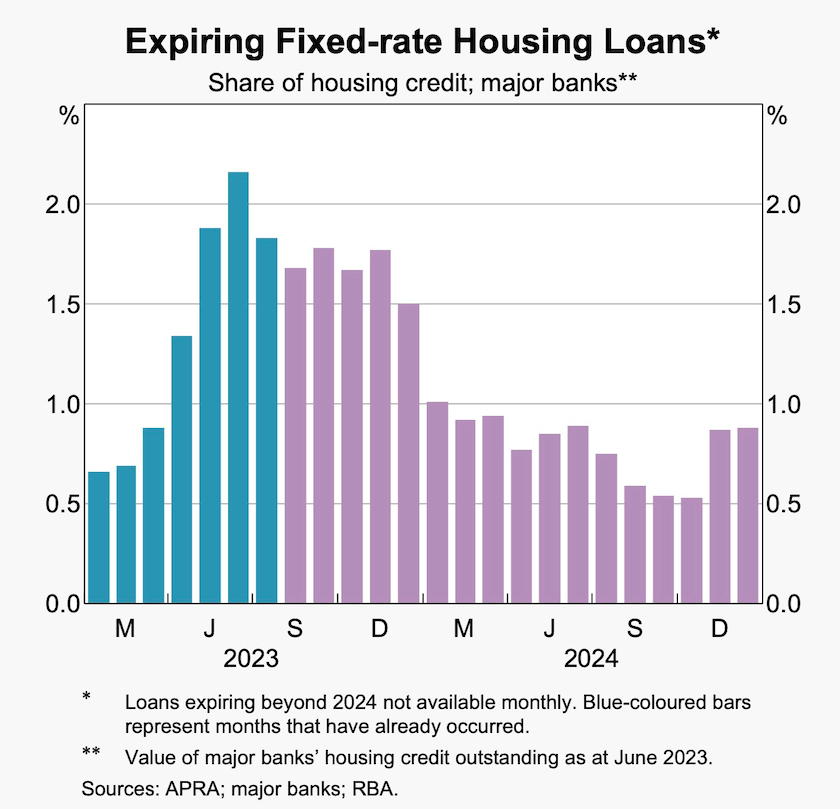

We may be past the peak of low-interest fixed-rate loans maturing. The graph below, copied from the Reserve Bank August Statement on Monetary Policy (Page 46), shows that the expiry of such loans peaked in July. There will still be a fair few loans expiring for the rest of the year, but most of the shock of re-financing will be over early next year.

In its article Are we there yet? A ‘fixed-rate cliff’ update Core Logic offers some optimism about mortgage stress, pointing out that up to March, at least, there was little sign of mortgage stress: the percentage of housing loans in arrears is trending downwards.

Another note of optimism is in APRA’s March statistics on the financial sector’s exposure to the property sector. As indicated by continuing falls in loans with high loan-to-value ratios and high debt-to-income ratios, financiers have been becoming more cautious. That means people presently taking mortgages are less likely to face severe stress than those who bought houses over 2020 and 2021.

Core Logic also presents some evidence that the growth in house construction costs may be easing – but there is still a low rate of housing approvals compared with the pre-pandemic period.

All this easing of stress is down the track, however. For now some, particularly younger mortgage holders, are having a tough time financially, and many are dipping into their savings or cutting back on what they may have previously considered to be essential expenditure, such as car insurance.[1] The ABC’s David Taylor, in an article on changing consumption patterns, presents data provided by the Commonwealth Bank, showing that its older customers are doing rather well: customers under 34 are drawing down their savings, while older customers, particularly those over 56, are building up their savings while also spending more than before.

1. A general belief is that it is reckless to cut back on insurance, but it is always wise for people to review insurance policies, to find savings by holding policies with high deductibles, and to drop unnecessary insurance. It can be particularly useful to review one’s holding of health insurance, which is generally poor value-for-money and offers only limited cover for health care shocks. ↩