Economics

What’s going on at the Reserve Bank?

Philip Lowe’s chances of being re-appointed as Reserve Bank Governor were about the same as Labor’s chances of winning the Fadden by-election.

Media attention has turned to Michele Bullock, who has been Deputy Governor. There is a short biographical note about her on the RBA website. Her economic credentials are sound (BEc Hons University of New England, MSc London School of Economics), but the most telling part of her experience is that she has been involved in the often-unnoticed administrative functions of the Bank.

Writing in The Conversåation Isaac Gross of Monash University provides a more expansive biography of Bullock, and reasons why Lowe was not re-appointed: Meet Michele Bullock, the RBA insider tasked with making the Reserve Bank more outward-looking as its next governor.

It’s easy for commentators to forget that the Reserve Bank is governed by a board, that the board is supported by a staff of well-qualified economists, that the Bank’s responsibilities are specified in an Act of Parliament, and, perhaps most importantly, that monetary policy operates within an established economic tradition. Also, as the government has announced, the Bank’s governance arrangements are changing: it is to have a board specifically concerned with monetary policy. (Journalists and other commentators generally put too much focus on organizations’ CEOs.)

This broader consideration is the subject of a Saturday Extra session where Geraldine Doogue interviews Jonathan Kearns, formerly an RBA department head, and Richard Denniss of the Australia Institute. It’s titled New RBA Governor Michele Bullock, but it’s really not about her. It’s about the RBA, its well-protected insularity, and the narrow economic lens through which it views the world.

Richard Denniss is particularly critical of its obsession with wages, and its tendency to ignore corporations’ market power as a driver of price inflation. He points out that the RBA has been dismissive of not only the Australia Institute’s analysis about corporate profits, but also of the same analysis presented by the IMF, the OECD and the US Fed, all of which have said similar things.

On where monetary policy is likely to go, Alan Kohler, writing in the New Daily, says that Bullock has been set up to succeed. She has embraced the Bank’s governance changes enthusiastically, and the global supply-side forces that were driving up prices are weakening.

Yet again: firms’ market power, not wages, have been driving inflation

The minutes of the Reserve Bank July meeting confirm that its decision not to increase interest rates was a close call, and that they are keeping their options open: “Members agreed that some further tightening of monetary policy may be required to bring inflation back to target within a reasonable timeframe” – whatever a “reasonable timeframe” may be.

In an upbeat assessment of the economic outlook, Peter Martin writes in The Conversation that Australia is on the brink of ending interest rate hikes and an economic first – beating inflation without a recession. Inflation, having peaked about a year ago, is definitely falling in the “western” world, including Australia, and importantly, inflationary expectations are falling. Martin believes that Australia can enjoy low unemployment and low inflation. In a credible dismissal of the simple inflation-unemployment trade-off that governs monetary policy (the Phillips curve), he writes:

Things get easier when unemployment is low. We get more likely to become more productive, because we’re less resistant to change when unemployment is less of a threat. We get in a better position to help the budget, by taking less in benefits and paying more in tax. And we become more like each other – lessening inequality.

It looks as if the Reserve Bank has the opportunity to cement low unemployment while controlling inflation. Holding off (and perhaps abandoning) future rate raises will keep it in reach.

Ross Gittins and Crispin Hull, in different ways, remark that the crude instrument of monetary policy – reducing the money supply in order to reduce demand and therefore to reduce inflation – doesn’t work, because that model assumes a high degree of competition in the economy. Gittins, in his post Less competition reduces the power of interest rates to cut inflation, cites research showing that neither labour markets nor goods markets behave according to the monetarists’ models.

So, whether it’s inadequate competition in the markets for particular products, or inadequate competition in the market for workers’ labour, lack of competition makes monetary policy – moving interest rates – less effective than central bankers have assumed it to be.

Hull makes the same point about firms’ market power, while adding some behavioural insights, in his post Reserve banks lose leverage. Even if the RBA’s big lever – controlling interest rates – worked in the past, it isn’t working now, because the economy has changed, partly because households’ and firms’ response to the Covid-19 recession did not align with economists’ models.

You cannot, as in the past, just increase interest rates and expect household demand to tighten and for firms to respond by decreasing prices to continue to attract custom with a concomitant reduction in inflation.

He goes on to write:

The interest-rate levers are no longer effectively connected to the brakes or the engine. We need more than just interest rates to control inflation. We need greater productivity; more competition; a more efficient and equitable tax system; and most importantly the political courage to make the changes.

Gittins and Hull both make the point that the RBA’s big lever is ineffective. The ABC’s Ian Verrender goes one further. He points out that in relation to energy prices – a major component of the CPI – increases in interest rates can actually contribute to higher inflation. The lever is actually working in the wrong direction. That’s because of the way our gas and electricity utilities are regulated, allowing them to pass on higher interest rates as higher prices: How higher interest rates are boosting inflation.

Unemployment and underemployment are causes of suicide

That’s the title of a paper by four researchers, from disciplines of mental health and mathematical techniques, published in Science Advances, demonstrating with high confidence that there is a causal link between unemployment (including underemployment) and suicide.

It has long been known that there is a correlation between unemployment and suicide, but as teachers emphasize, correlation does not necessarily signify causation.

Using a technique known as “convergent cross mapping”, which can reveal causal relationships in noisy time series, the researchers are able to state that 9.5 percent of suicides reported in Australia between 2004 and 2016 “resulted directly from labor underutilization”.

They conclude that “economic policies prioritizing full employment should be considered integral to any comprehensive national suicide prevention strategy”. That means an economist, working for the Reserve Bank or Treasury, should urge policymakers to consider suicide as one of the costs of unemployment.

The authors have a summary of the report in The Conversation, with a discussion about how greater awareness of the consequences of unemployment should shape public policy. They “hope to provoke a deeper conversation about the design of the economy and how it values people, beyond simply making money”.

Do governments have the courage to confront gambling companies?

The USA has dangerously loose gun laws and the National Rifle Association determined to keep them loose. We have dangerously loose laws on gambling and the powerful gambling lobby. The USA has the AR-15 assault rifle. We have poker machines.

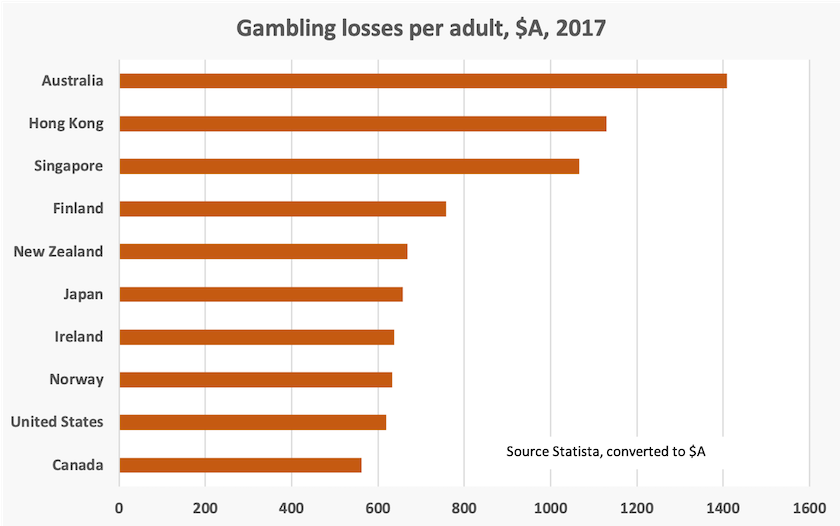

Just as the USA stands out for firearms deaths, we stand out for gambling losses – at least $1400 a year per adult.

Unlike gun control in the US, at least our governments are doing something to counter problem gambling. Tasmania has taken the strong initiative of a cashless gaming card with pre-commitments, and Western Australia has the buffer of isolation: poker-machine gambling broke out in New South Wales in the 1950s and spread like a virus through the eastern states, but it didn’t cross the Nullarbor. In other states there is reform, but it is slow and timid. For example in New South Wales the previous Coalition government had promised to follow Tasmania’s lead with a cashless gaming card, but the recently-elected Labor Government has committed to introduce it only on a trial basis. (Presumably they need to be assured that there is not some genetic difference between the people of New South Wales and Tasmania, regulating their predilection to gambling addiction.)

Last week Victoria announced a set reforms, including mandatory pre-commitment and carded play, slower operation of poker machines, and compulsory closing hours for gambling venues. On ABC Breakfast Fran Thorn of that state’s Gambling and Casino Control Commission and Charles Livingstone of Monash University discuss the reforms. (3 minutes) The reforms have been welcomed by the Alliance for Gambling Reform, who would like the New South Wales government to be a little more courageous: Vic poker machine reforms applauded “significant and meaningful”. Changes now put spotlight on NSW to do more to reduce gambling harm. Livingstone, however, is worried that the Victorian government could lack the political courage to implement the reforms: Victoria cracks down on pokies but supporters fear interest groups could hold the winning hand, published in The Conversation.

That’s promising progress on poker machines, regulated by state governments. Charles Livingstone, in a Conversation contribution – Australia has a strong hand to tackle gambling harm. Will it go all in or fold? – draws attention to the recent report by the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Social Policy and Legal Affairs You win some, you lose more, which seeks a national ban on all forms of advertising for online gambling, to be introduced in four phases:

Phase One: prohibition of all online gambling inducements and inducement advertising, and all advertising of online gambling on social media and online platforms. Removal of the exemption for advertising online gambling during news and current affairs broadcasts. Prohibition of advertising online gambling on commercial radio between 8.30-9.00 am and 3.30-4.00pm (school drop off and pick up).

Phase Two: prohibition of all online gambling advertising and commentary on odds, during and an hour either side of a sports broadcast. Prohibition on all in-stadia advertising, including logos on players’ uniforms.

Phase Three: prohibition of all broadcast online gambling advertising between the hours of 6.00 am and 10.00pm.

Phase Four: by the end of year three, prohibition on all online gambling advertising and sponsorship.

The dividends of privatization

Privatization of government services was supposed to bring great benefits.

It certainly has – to the owners of those assets.

Attention is currently focussed on the way the work of the Commonwealth Public Service has been handed over to big consulting firms, which have paid their partners eye-watering incomes, have breached confidence, and have shaped their advice to provide ministers with what they wanted to hear. On these matters the media are keeping us well-informed of the relentless work of Senators Barbara Pocock (Green) and Deborah O’Neill (Labor). They are exposing the direct costs of such privatization (at least $10 billion over the last ten years), but the cost of poor public policy would be many times more.

Two other cases of privatization that have come to our attention over the past week involve physical assets – electricity infrastructure and toll roads.

Electricity infrastructure

Producers’ coal, gas and oil prices have plummeted in the last few months. Gasoline prices have fallen in line, but as Ian Verrender points out, households have not enjoyed lower gas and electricity prices. That’s largely because only a small part of households’ bills relates to the cost of generating electricity or extracting gas. About half of the bill is for the pipelines, transmission lines and transformers that deliver gas and electricity to homes and businesses. The owners of those assets are largely foreign firms that acquired them from state governments.[1] Regulators allow those owners an unjustifiably high return on their investment, based on business models that provide an unrealistically high allowance for risk, even though these are really risk-free investments. As interest rates rise, so are those firms able to raise their prices and enjoy higher incomes.

Another burden placed on consumers by privatization has been the privatization and break-up of the state electricity utilities, separating “retailers” from the other part of the supply chain. These “retailers”, whose simple task is to arbitrage between wholesale prices (which change rapidly) and retail prices, do not serve customers well.

In imposing a layer of bureaucracy in the supply chain these “retailers” add to consumers’ costs. Then there is their use of price discrimination – charging high prices to people who lack the time or ability to shop around – results in many people paying far too much for electricity and gas. The ABC’s Rhiana Whitson points this out, drawing on analysis by the ACCC: Millions of Australian households paying too much for electricity, according to ACCC. (The ACCC document to which Whitson refers is part of its ongoing reporting, to be found on the ACCC website.) And because they are only billing companies, with no physical relation with electricity, if there are problems such as power surges or blackouts, they can absolve themselves of responsibility. Customers are left uncovered because their relationship is only with the “retailer”, not with the distribution company operating the faulty transformer.

Australia didn’t need this break-up and privatization. The state-owned electricity utilities had been generally doing a good job. Electricity is a basic commodity, and its transmission and distribution use long-established technologies: there are no benefits of product or process innovation that are supposed to come from privatization. Privatization was driven by economists ignorant of the industry’s technologies, and by governments who sold valuable assets at low prices in order to balance their cash budgets.

Toll roads

Perth, Adelaide and Canberra have so far been spared the idiocy of toll roads, but they are part of the network in Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane.

Apart from a fringe anti-road movement, who seem to misunderstand the function of urban roads, few people would dispute the benefit of freeway-standard roads in our cities. They serve purposes that even the best public transport systems cannot serve. They are used by those delivering goods, tradespeople who carry their tools of trade, and by those who have complex journeys with multiple destinations. They take heavy traffic away from suburban roads, and in allowing traffic to move steadily they reduce pollution generated by stop-start traffic.

Leave it untolled

Those benefits are not fully realized, however, if the roads are underused, when potential users are dissuaded by tolls.

Economists refer to such under-use of assets as “deadweight loss”, in that no one benefits when a truck driver takes a rat-run through suburban streets to avoid a toll. Some of those tolls are substantial – typically around $30-$40 for trucks.

The New South Wales Government is currently running an inquiry into tolling in Sydney, conducted by Allan Fels and David Cousins. The inquiry’s discussion paper puts to the public various tolling options including time-of-day pricing, CBD cordon pricing, and fines for heavy vehicles rat-running. In public consultations it has already been revealed that truck drivers are using suburban roads at night to avoid tolls, often in conflict with local governments that attempt, with good reason, to impose curfews on heavy vehicles.

Our cities need these roads, but charging for high quality roads in an otherwise “free” network is poor public policy. Obviously they have to be paid for, but that can be through gasoline taxes or road user charging, which is becoming technologically more realistic. An ideal system of road user charging would charge heavily those users who choose not to use urban freeways.

Fels and Cousins, both of whom have impeccable credentials as economists who understand consumer and behavioural economics, will no doubt produce some sound recommendations when they report to the government next year, but their work will be bound by existing contract arrangements between the state government and toll road operators, one of which (Westconnex) lasts until 2060.

Perhaps the best we can hope from the review is that other cities won’t go down the path our biggest cities have taken, and find ways to fund urban roads through more economically responsible means than privately-owned toll roads.

1. In Tasmania, Queensland and Western Australia most transmission and distribution assets are government-owned, but in corporatized entities, which means their incentives are in line with profit-maximizing businesses, rather than community service as had been the case with the state electricity utilities. At least the excess profits remain in Australia. ↩

Inequality in Australia – slow progress in some dimensions, rapid worsening in others

Most commentary on inequality is about the distribution of income, and doesn’t go much further.

Per Capita’s Australian Inequality Index fills that space by drawing on time series data to examine seven dimensions of inequality over the period 2010 to 2021. They develop indexes of income inequality, wealth inequality, gender inequality, intergenerational inequality, ethnicity inequality, disability inequality and First Nations inequality.

Wealth inequality shows the widest opening of disparities over that period, particularly after 2013. Intergenerational inequality followed a similar pattern. (They leave it to the reader to recall that the Abbott government was elected in 2013.) There has been substantial improvement in gender equality and very slow improvement in First Nations equality.

Per Capita’s site has an interactive tool that allows users to see how long it would take for inequalities to close, based on trends derived from the data. (That is, where there is an improving trend.) Note that there have been significant departures from the trend lines in 2020 and 2021, the years of the pandemic.

This work should be a useful policy-related input into the government’s development of a wellbeing framework.