Health policy

We have plenty of hospital beds, and plenty of doctors. So why are our hospitals overstressed?

Compared with other “developed” countries (many of which have older populations), Australia has more hospital beds, more GPs, and more practising nurses in relation to our population. So why are our public hospital emergency departments overloaded, why are our waiting times for elective surgery so long?

Martyn Goddard addresses these issues in his Policy Post article: It was the biggest health reform since Medicare. It didn’t work.

The reform to which that headline refers is activity-based funding (known as “diagnostic related group” funding) for public hospitals, which, Goddard explains, did not account adequately for scale economy differences between small and large states. He demonstrates how DRG funding has effectively involved a transfer of Commonwealth funding from small states and territories to large states.

He also explains why in spite of adequate resources we have crowding in emergency departments and long elective surgery waiting lists. In short we don’t get the most out of our health services. There are many people in hospital who should be getting care in other health care establishments. And we are not using our health-care workforce efficiently – too much is loaded on GPs while nurses are under-utilized.

He mentions the distortion of having a private hospital system operating alongside a public hospital system, with entirely different payment systems and incentives. “Why should a top surgeon work in the public system for $300 000 a year when he could get ten or fifteen times as much in private practice, where there is no control on earnings?”, he asks.

While he identifies the way health care resources are misallocated, he makes no mention of private health insurance, which is perhaps the biggest driver of this misallocation. It’s little wonder that there are long waiting lists for public hospitals when the Commonwealth, through its generous subsidies to private health insurance companies, is incentivizing patients to jump the queue.

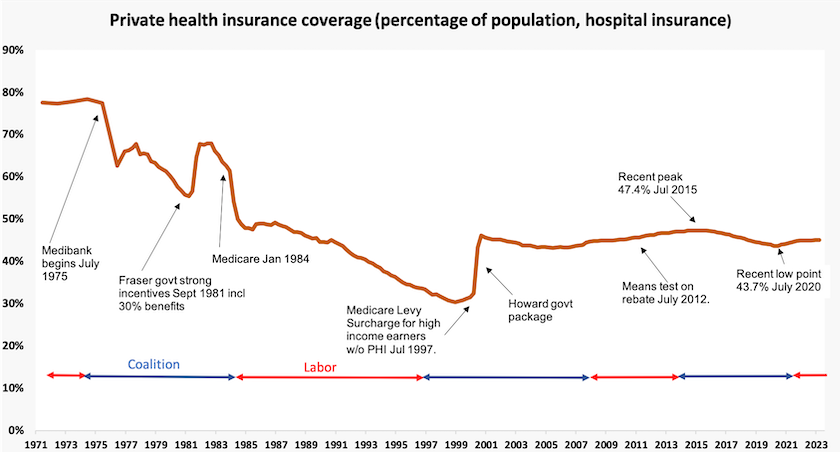

The graph below shows a short history of private health insurance over the last 50 years. The Whitlam and Hawke-Keating governments took strong measures to rid our health system of this curse. By 1997, a year after the Keating government had left office, PHI membership was down to 30 percent and was well on the way to petering out.

At great public expense the Howard government re-introduced incentives for PHI, and the subsequent Rudd-Gillard government did nothing to arrest the slow rise in PHI. PHI membership fell during the pandemic, possibly because for a short time state governments were contracting private hospitals to serve public patients, but it is now rising again, even though it should be an easy item to ditch for households feeling financial stress. The graph below summarises this history.

Why is dental care (still) not covered by Medicare?

There is little logic in excluding dental care from Medicare. Dental care is unaffordable for many Australians, and neglect of dental care has consequences for health outcomes generally, imposing public and private costs on the whole health care system. Excluding dental care from Medicare is not only unjust: it is also a false economy.

Writing in The Conversation – Expensive dental care worsens inequality. Is it time for a Medicare-style “Denticare” scheme? – Lesley Russell of Sydney University’s Menzies Centre for Health Policy describes how dental care came to be left out of Medicare, and how Coalition governments have made sure it remains left out. She notes that one of the first things the Howard government did when elected n 1996 was to abolish the Commonwealth Dental Health Program.

She draws attention to the Interim Report of the Senate Select Committee into the Provision of and Access to Dental Services in Australia which shows that the government contribution to spending on dental care is low by international standards, that there is a great amount of unmet need, and that the cost of dental care is a major factor in dissuading people from getting dental care.

Covid-19 is still hanging around, but so too are other respiratory diseases

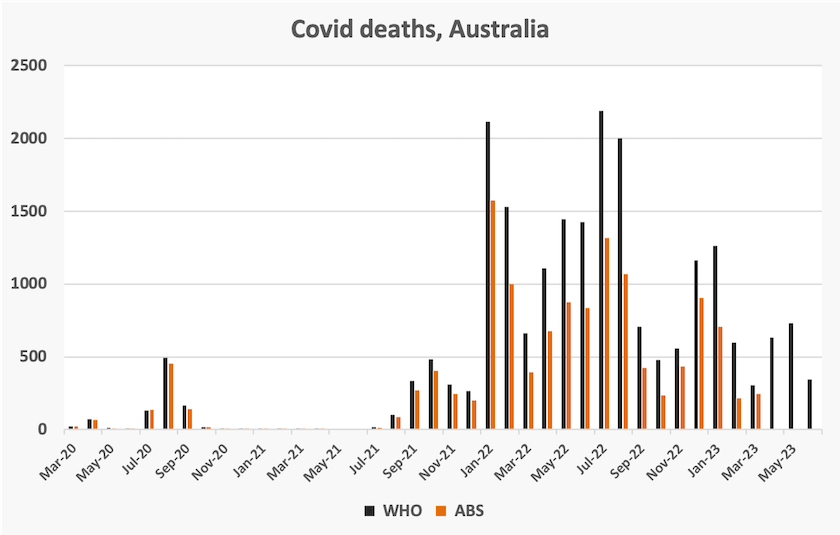

The Commonwealth’s weekly Covid-19 reports reveal that Australians are still dying with, or of, Covid-19 – about 18 a day. In Australia Covid-19 is occurring in waves some months apart, with each wave being less intense than previous waves – a pattern consistent with epidemiological models.

The graph below shows a history, month by month, of Covid deaths in Australia. The black bars are as reported by our government to the WHO, while the orange bars are as estimated by the ABS. Part of the difference is because of timing of notification and recording, but the main difference is that the ABS records only cases where Covid-19 is the probable cause of death, rather than a co-existing condition at death.

Recent New South Wales Respiratory Surveillance Reports show that while Covid-19 hospital admissions are continuing to decrease, they are being overtaken by influenza and other respiratory-related admissions. For 2022 and 2023 so far, the “all cause” death rate per 100 000 population has been high in relation to long-term seasonal patterns. The 2022 winter spike of deaths was high, but about the same magnitude as the 2017 spike, associated with the high rate of influenza in that year. The 2023 spike, so far, does not appear to be as severe as it was in 2022 or 2017.

Drugs of addiction – a worldwide problem

There are at least two dimensions of problems relating to drug addiction. One relates to health effects of addictive and other harmful drugs. The other relates to the harms involved in the production and distribution of illicit drugs.

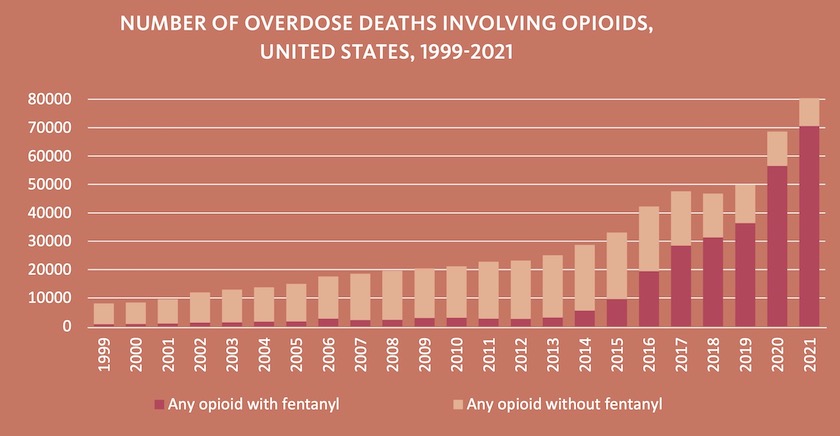

Both dimensions are covered in the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime World Drug Report 2023. Cocaine and opioids are both prominent in the production and distribution of illicit drugs: coca bush and opium poppy production are both rising quickly. But opioids, often legally supplied and produced, account for 69 percent of deaths due to drug use.

The report stresses how social and economic inequalities drive, and are driven by, drug production, distribution and use. This report draws particular attention to issues in the Amazon Basin:

The drug economy in the Amazon Basin is exacerbating additional criminal activities – such as illegal logging, illegal mining, illegal land occupation, wildlife trafficking and more – damaging the environment of the world’s largest rainforest. Indigenous peoples and other minorities are suffering the consequences of this crime convergence, including displacement, mercury poisoning, and exposure to violence, among others. Environmental defenders are sometimes specifically targeted by traffickers and armed groups.

An alarming finding in the report is the prevalence of deaths from the pain-killer fentanyl in the US, shown in the graph below, copied from the report.

Australia (as yet), is relatively untouched by fentanyl. As in the USA cannabis is Australians’ drug of choice. In Australia amphetamines and other stimulants account for 49 percent of people receiving treatment for drug use, and opioids 11 percent. In the US opioids account for 43 percent of people receiving treatment.

An estimate of the impact of fentanyl in the US is provided in a Council on Foreign Relations paper by Claire Klobucista and Alejandra Martinez: Fentanyl and the U.S. Opioid Epidemic. To put its costs into perspective they point out that those 80 000 deaths in 2021 were “more than ten times the number of U.S. military service members killed in the post-9/11 wars in Iraq and Afghanistan”. They estimate that the opioid epidemic is costing the US 7 percent of GDP.

We shouldn’t be smug about our comparison with the US. Authorities warn that fentanyl is easy to manufacture and because it is so powerful in relation to other opioids drug dealers can make large profits on easily-smuggled small consignments.

The ethics of health policy

Stephen Duckett has an impressive record of public service. As an academic health economist he has been an advocate for economically responsible and socially just health policy. He has been head of the Commonwealth Department of Human Services and Health, and most recently he has been head of the health program at the Grattan Institute.

His most recent contribution is a book Healthcare funding and Christian ethics. In a short (10 minute) but wide-ranging interview on the ABC’s Religion and Ethics Report he discusses the ethics of health care in a public policy setting.

This discussion is anchored in the Parable of the Good Samaritan – a story about inclusion, trust and equity. He goes on to discuss the moral choices policymakers faced during the early days of the pandemic, and the ways health administrators, with constrained budgets, are guided to allocate scarce resources. It’s always a difficult task, but one that can be guided by a strong moral framework.