Australia’energy transition

Our nation’s path to green energy

“Decarbonise electricity and electrify everything”.

That’s a quote from Alan Finkel’s book Powering up: unleashing the clean energy supply chain, reviewed by John Quiggin in The Conversation: We need to decarbonise our electricity supply, and quickly – Alan Finkel shows how green energy can be a reality, and bring economic benefits.

As Quiggin points out, that statement hides many complexities. Finkel covers them in his book, including an explanation of the distinction between energy and power (a distinction most journalists miss – did they doze off during Year 10 physics?), characteristics of different technologies to supply and conserve energy, and the availability of critical minerals for electrification. He also charts a realistic policy pathway towards a hydrogen economy.

More specifically, a group of researchers from Geoscience Australia and from Monash University have written in The Conversation about the physics, geography and economics of building green hydrogen plants next to green steelworks, which would boost the efficiency of both industries. We have all the necessary resources to do this: the task is to bring them together.

Even if the use of green hydrogen in steelmaking is still some time off, the industry can be largely decarbonized by use of electric arc furnaces, powered from renewable resources, replacing blast furnaces, as is happening at Whyalla.

The regional path to green energy

It is a valid proposition that more economic activity, including well-paid employment, will result from our transition to green energy than will be lost from the closure of domestic and export coal mines, and from the closure of gas and coal fired power stations. The regional consequences will be uneven however, particular where there has been a concentration of fossil-fuel based industries. In some cases renewable energy installations will replace gas and coal power stations, plugging into the high-voltage power lines, but they are likely to be much less labour-intensive operations.

The Centre for Policy Development has studied the economic adaptability of 11 local government areas in Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria and Western Australia, all exposed to declining demand for fossil fuels: Making our way: adaptive capacity and climate transition in Australia’s regional economies. All 11 have low levels of economic diversity, but there is a wide dispersion of opportunities for these communities to cope with the transition. Some, for example, are well connected to domestic markets, while others are isolated.

The CPD has a number of policy recommendations, most notably that there should be local transition plans for such regions, aimed at strengthening overall economic resilience and adaptability, rather than focussing solely on new anchor industries.

The transport path to green energy

Do they really need all that weight?

While there has been a great deal of attention to reducing emissions in electricity generation, there has been less attention to the transport sector, other than a few minor incentives for people to take up electric cars.

Writing in The Conversation, Robin Smit of Sydney’s University of Technology warns that Australia is not on track to reduce road-transport emissions: Too big, too heavy and too slow to change: road transport is way off track for net zero. He refers to research by the Clean Air Society of Australia and New Zealand, forecasting that with present policy settings road transport emissions by 2050 will be only 35 to 45 percent below 2019 pre-Covid levels – a long way from zero.

He explains why the immediate priority should be a move to smaller and therefore lighter vehicles of all types – fossil fuel and electric powered. Even for EVs weight is important, because until our electricity is 100 percent from renewable resources they will be contributing to emissions. The medium-term policy solutions should involve “public information campaigns, tax incentives for small, light vehicles, bans on selling fossil fuel vehicles and programs to scrap them”.

Smit’s contribution is about greenhouse gas emissions. SBS News reminds us of other problems with heavy vehicles, mainly that they’re dangerous and they wear out our roads: Australians love heavy cars. Why is that a problem? After all, a cyclist or pedestrian run over by a carelessly-driven vehicle isn’t particularly concerned about that vehicle’s power source. (Cyclists are particularly wary of quiet EVs).

The SBS article cites data from the Federated Chamber of Automotive Industries showing that heavy SUVs made up more than half of all vehicles sold last year, and that the average weight of new vehicles is now 2.05 tonnes, close to the weight of two Volkswagen Polos.

The world energy landscape – a mammoth task ahead

“Global energy-related greenhouse gas emissions are still heading in the wrong direction”.

In 2022 carbon emissions from energy use, industrial processes, flaring and methane reached a record high of 39.3 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent – an increase of 0.8 percent over 2021.

These are the headline summaries from the Energy Institute’s 2023 Statistical Review of World Energy, a compilation of data on energy production, consumption, trade and emissions.

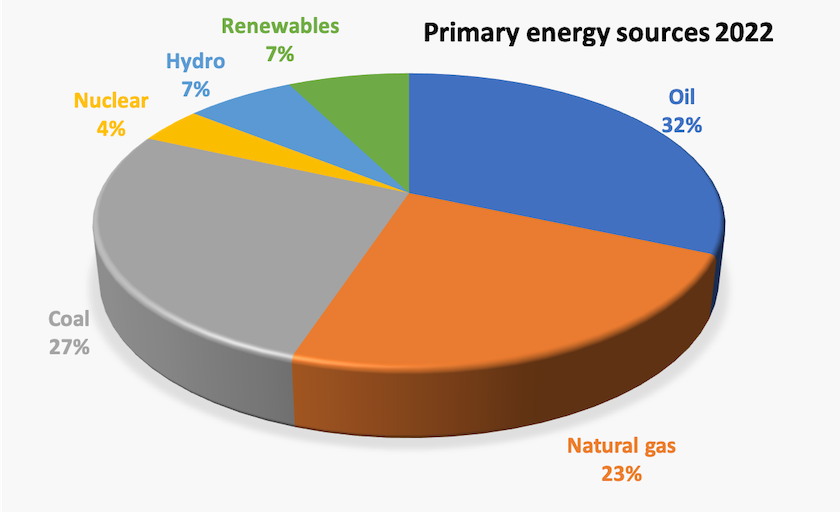

Renewables account for 7.4 percent of the world’s total energy supply – up from 6.6 percent in 2021. Hydro energy accounts for a further 6.7 percent and nuclear 4.0 percent of total supply. The rest, 81.8 percent, is from fossil fuels. Oil still accounts for a third of energy supply.

Renewable energy (other than hydro) has continued to grow as a source of electrical power, but still accounts for only 14 percent of global power generation. In Australia that figure is 27 percent, but we can do much better in view of our potential resources.

Worldwide, the shares of coal and nuclear fission in electricity generation have continued to fall. Even though the trajectory of costs strongly favours renewable sources (supplemented by storage and demand management) over nuclear, there are still Coalition politicians advocating nuclear energy for Australia.

The Energy Institute’s review reminds us that coal is still the major source of electrical power in China (61 percent) and India (74 percent).

Writing on the Energy Monitor website, Justin Guay of the Sunrise Project points out that worldwide there needs to be $US4.6 trillion invested every year by 2030 to meet net-zero goals (think the GDPs of two Australias), but we are $3.6 trillion short of that. His article To unleash the clean trillions we need more sticks, less carrots argues for deals where public investment for green energy is linked to incentives and regulation requiring the private sector to do its part.

The geopolitics of the world’s energy transition

In Australia we are concerned with the politics of our own energy transition. The more complex politics of the world energy transition are described in a Foreign Affairs contribution by Jason Bordoff of Columbia University and Megan O’Sullivan of Harvard’s Kennedy School: The age of energy insecurity: how the fight for resources is upending geopolitics.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine set off a bout of price manipulation by oil-producing countries, reminding US, Japanese and European policymakers that in importing oil and gas from Russia they were financing Russia’s brutal imperialism, and bringing to memory the situation in the 1970s and early 1980s when a cartel of oil producers were able to wreak havoc on the world economy while shifting the geography of financial power.

For reasons to do with the geographic distribution of energy resources (green resources being available to almost all countries) and to do with the need to combat climate change, energy self-sufficiency is now back on the agenda for many countries.

“But at least for the next few decades, energy security will be advanced not through more autonomy but through more integration—just as it always has been” the authors warn. “Interconnected and well-functioning energy markets increase energy security by allowing supply and demand to respond to price signals so the entire system can better handle unexpected shocks”.

There will be shocks, including some resulting from extreme weather events brought on by global warming. In establishing new means of energy cooperation the political relationships will be different from those of the past, the authors state.

One example of cooperation brought about by these geopolitical changes is the recently-announced Australia-United States climate, critical minerals and clean energy transformation compact.

Vale Hugh Saddler

Hugh Saddler, described by the Australia Institute as “a titan of Australian energy research”, died last week.

The Australia Institute has a short obituary to Hugh: Vale Dr Hugh Saddler, Leading Australian Energy Researcher & Founding Board Director of the Australia Institute.

Right up to the end Hugh was researching and publishing on energy matters. Just a few days ago Industry Search published his article pointing out that Australia’s electricity consumption has fallen significantly as businesses and households adapt to higher prices, meaning that even as prices rise by 20 to 25 percent, electricity bills are rising by a lesser amount. He always saw it important to respond to politically-inspired misinformation about energy and to clarify the engineering of green energy.

For me his passing is the loss of a friend and a colleague who has been a source of well-considered professional opinion on energy issues.

His funeral will be at 1500, next Thursday July 13, at Canberra’s Norwood Crematorium, and live streamed.