Economics

Inflation – has the RBA overshot?

The media are giving a great deal of attention to the ABS Monthly Consumer Price Index Indicator for May. The standard headline is that inflation has fallen to 5.6 percent, and the standard question is whether the Reserve Bank will lift interest rates when it meets on Tuesday.

Even leaving aside the issues in calling the CPI a measure of “inflation” (that’s a big issue in itself), that 5.6 figure is probably a significant overstatement of current inflation. It’s simply a measure of the change in that indicator between May 2022 and May 2023. In fact in comparison with April, the indicator actually fell a little in May, from 119.5 to 119.0, and on a seasonally-adjusted basis it did not move at all. If journalists bothered to look at the data provided by the ABS they could say that inflation is now zero, or even negative.

That would be a rough estimate, however, because those two numbers have errors of estimate. It’s rash to base any movement on the difference between two numbers with a significant error of estimate. But if enough data points are taken into account a trend can be inferred.

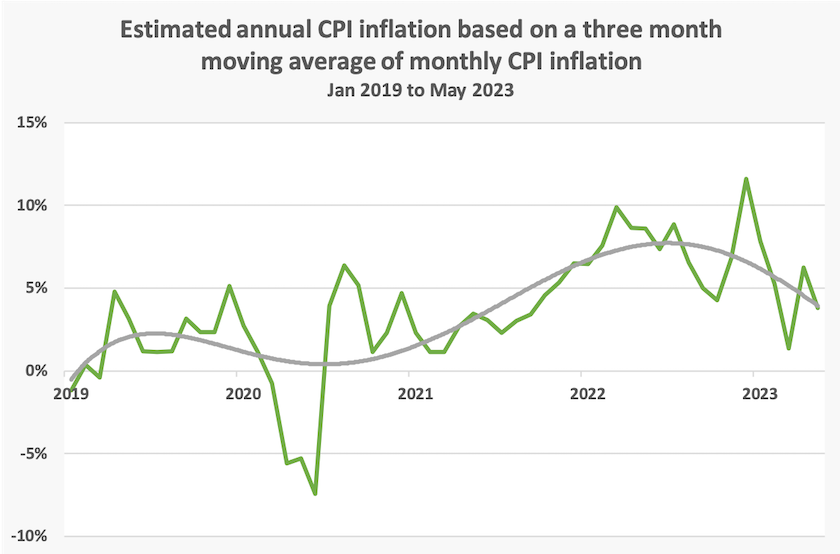

The graph below shows a three-month moving average of monthly CPI inflation, annualized, and a smoothed line (a fifth-order polynomial best fit) of monthly estimates going back to January 2019. It suggests CPI inflation in the three months to May was 3.8 percent – say “four percent” to avoid any impression of spurious accuracy, and that it peaked around the middle of last year at about eight percent.[1]

When the RBA announces its interest-rate decision on Tuesday, will it follow its usual habit of categorically stating that “inflation is 5.6 percent”, or will it be more cautious and say something like:

CPI inflation over the year to May was about 5 to 6 percent. The most recent data from the ABS suggests it is now around 4 percent, and is on the way down.

There is a promising sign that the RBA is explaining its activities in a more sophisticated way. Perhaps it is tentatively moving away from its “Phillips curve” model – a pseudo-mathematical model that suggests that all that has to be done to control inflation is to ensure that 100 000 people lose their jobs so that the rest of the workforce becomes more placid. The Australia Institute points out that in the published minutes of its June decision it actually acknowledged the role of corporate price hikes in contributing to inflation. Members of the board observed that:

… some firms were indexing their prices, either implicitly or directly, to past inflation. These developments created an increased risk that high inflation would be persistent, which would make it more difficult to keep the economy on the narrow path.

If firms are linking price increases to past inflation, that provides a strong reason for the RBA to talk about what it believes inflation to be now, even if that has to be a qualified statement, rather than using an overstated figure from the past 12 months.

1. Annualization is based on normal compounding – i.e. (((Latest month’s index/Previous month’s index) ^12) -1). This yields a slightly higher figure than 12 X the latest month’s growth. ↩

An economic optimist

Economist Justin Wolfers, in an interview on ABC Breakfast, notes that he has never seen such a disjunction between economic reality and newspaper headlines. As if to illustrate his point (but probably unintentionally), the editor of the website has titled the 7-minute interview Global economy at risk of recession, even though Wolfers’ message is reasonably upbeat.

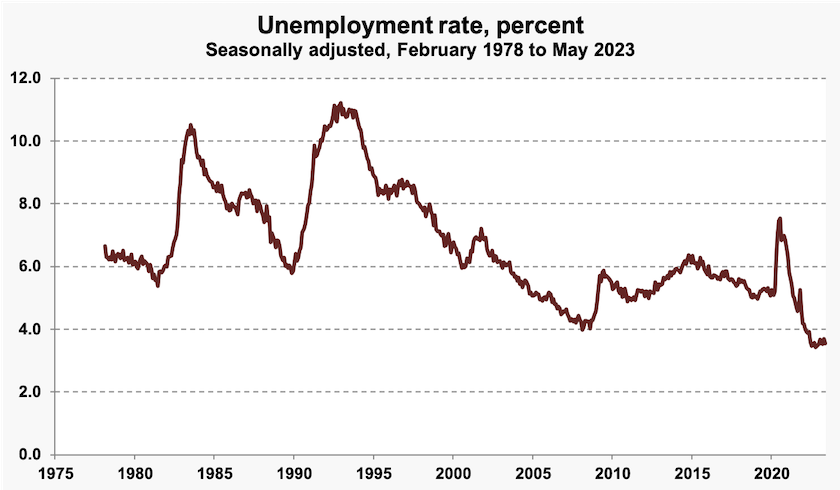

There is indeed talk of a recession, there is inflation, and many (but not all) people are having a hard time making ends meet. But in most “developed” countries, including Australia, unemployment is at a 50-year low, and when asked about their personal situation, even if they are unsure about the national economy, most people are optimistic about their personal opportunities. They have employment and should be able to muddle through temporary difficulties.

A little inflation as we are now experiencing is a minor burden compared with the misery of unemployment: “inflation is bad, but it does not sap the soul” Wolfers says.

Listing the factors that contribute to inflation, he does not mention rising wages. In fact he stresses that one of Australia’s economic weaknesses is that wages have not been rising fast enough. He believes that there is an obsession with wages in Australia, as if all wage rises are unaffordable, or will result in runaway inflation. “I don’t think Phil Lowe has ever seen a wage rise that he approves of”, he says.

There is too much talk about a possible “recession”. Wolfers wisely does not define a “recession”, simply saying it’s a technical term. (If anyone wants to go into definitions, the Reserve Bank has an informative web page showing how hard it is to define.) It suffices to point out that according to some technical definitions the economy can be in “recession” with little hardship and misery, and conversely that there can be considerable hardship and misery without the economy experiencing a “recession”.

Wolfers was born in Australia. He did his undergraduate studies at the University of Sydney, and a PhD in economics at Harvard. He is now Professor of Public Policy and Economics at the University of Michigan. That gives him a vantage point to see the Australian economy in perspective: in comparison with many other “developed” countries Australia is travelling reasonably well.

Another economic optimist

They will soon come on the market

JK Galbraith once said that pessimism generally carries an air of authority.

So it has been with several imagined economic crises, notes Alan Kohler in the New Daily: Crises that weren’t, aren’t, and never will be, plus one that really is heating up.

His attention in this article is housing. There won’t be a wave of defaults on mortgages: economic conditions have to get really bad for that to happen, because people do anything they can to hang on to their houses. (They may unload a few “investment properties”, however. In the long run that is no bad thing.)

When he considers the number of housing approvals and commencements over the last couple of years, he is reasonably optimistic that housing affordability will improve fairly soon as those houses are completed.

This suggests that the government may be on the right track in pulling forward assistance for public housing with its $2 billion appropriation. It could well abandon its silly Housing Australia Future Fund, which would provide assistance when it is least needed.

The crisis that isn’t getting attention is the return of El Nino, following an unusual run of three years of La Nina.

Western NSW in an earlier El Nino

You can see a concise presentation of Kohler’s argument, with a graphical presentation of housing supply and demand, on the ABC: Is the housing shortage as bad as we're being told?.

What’s driving corporate failures – the RBA or a delayed response to the pandemic?

Although the Reserve Bank Board is distressed to see the resilience of the labor market, it must be taking some joy from the growth in corporate insolvencies.

The media has been giving a fair amount of publicity to insolvencies, such as this article on an insolvency armageddon by Stephen Brook and Bianca Hall in the Sydney Morning Herald. In pointing out the growth in insolvencies up to April, it’s a little misleading because there is strong seasonality in the figures – firms don’t go broke in January. But as shown in the graph below, plotted from ASIC insolvency data, business insolvencies are now climbing back to pre-pandemic levels.

Building and construction companies are heavily represented in this wave of insolvencies. The ABC’s Jane Norman explains how house builders and their customers have been particularly impacted by a combination of fixed-price contracts, construction delays, and increased costs of materials and labour: Building company collapses turn home dreams into nightmares.

It’s hard to ascribe this general rise in insolvencies to any specific factor. The pandemic recession was unusual, because there were extraordinary measures in place, particularly “Jobkeeper”, keeping businesses afloat, and some banks extended repayment terms to business borrowers. We may simply be witnessing a return to normal conditions. After all, capitalism is a dynamic economic system, with an ongoing turnover of firms.

But surely the RBA’s aggressive interest rate rises have had some effect, particularly on those firms that have been getting by on high debt in relation to their equity. In many small businesses the proprietor’s personal assets and the business’s assets are not entirely separated: equity in the proprietor’s house is often used as security for a business loan. The Australian Financial Services Authority reports that after an extended period of decline, there has been a small increase in personal insolvencies.

In their article Brook and Hall note that many food service businesses are going to the wall. This may reflect the way so many retail and other shopfront businesses operate, because in a system that’s more characteristic of feudalism than it is to capitalism, most such businesses rent their premises from corporate landlords. The building owners have the power to pass on interest rate increases and to inflict terms on tenants that capture the lion’s share of surplus to themselves, leaving those tenants no buffer to see them through tough times.

Multinational taxation – a government backdown?

In 2021 the OECD announced that G20 countries had agreed to its Two Pillar Solution on taxing multinational companies, requiring them to pay at least 15 percent tax globally (rather than using accounting mechanisms to shift profits to tax havens), to limit interest payments companies use to shift profits, and to produce reports on their activities in each country.

In April 2022, Labor, then in opposition, announced grand plans to ensure multinationals operating in Australia pay their fair share of tax. This was to include the OECD requirements and was to require multinational firms to report publicly on beneficial ownership of assets, tax haven exposure, and activity in relation to government tenders.

The Tax Justice Network reports that Australia has been under pressure from multinationals and even from the OECD to delay its legislation, originally intended to come into effect on July 1, which would have required such reporting to be made public.

The ABC’s Nassim Khadem reports that multinationals, using the usual defences that such transparency would break conventions of commercial confidentiality and involve high compliance costs, have successfully fought off laws that would boost tax transparency.

Was $1 too much to pay for PwC’s government consultancy business?

PwC Australia has sold its government consultancy business to Allegro Funds for just $1.

Writing in The Conversation My Nguyen of RMIT University explains how such “peppercorn” deals work: You can’t buy much for $1, except maybe a global company. Why PwC could be sold for less than the price of a stamp.

One may wonder why $1? If, as it seems, that business has become a liability to PwC, why did they not pay Allegro to take it away?

Nguyen provides an answer, explaining that under new ownership, free of the PwC brand and whatever reputational damage that brand can inflict, another firm may be able to make a go of it. The liability is extinguished by a change in brand and a different owner.

A guide for landlords to get around rent freezes

Why do the Greens keep pushing the government to implement rent freezes as a condition of passing its Housing Australia Future Fund legislation, in spite of opposition from state governments and most economists?

In these roundups I have often referred to unintended consequences of rent freezes and rent controls. Writing in The Conversation Ameeta Jain of Deakin University spells out these consequences, including the development of a black market for rental properties, worsening the plight of people seeking affordable shelter: Rent freezes and rent caps will only worsen, not solve Australia’s rental crisis.

If ever any government is silly enough to institute rent controls, her article could become a useful guide for unscrupulous property owners seeking to fleece desperate tenants.

Build your own budget

You can run it all

It can be hard to fill winter nights with engaging activity.

But policy nerds can have hours of clean wholesome fun with the Build your own budget tool, developed by the Parliamentary Budget Office.

In fact it is a realistic model of the budget process, built around a set of Excel pages. If you do nothing other than to look at its tables and charts, you will see that it’s mainly a condensed presentation of the 2023-24 budget.

You can pretend you’re the treasurer, with unchecked power to set tax rates, the level of spending on big programs such as public hospital funding and defence, and the levels of certain social security transfers. In fact you have even more power than Jim Chalmers because you don’t have to worry about what Anthony Albanese, your cabinet colleagues, Labor Party pollsters, Ross Gittins, Ian Verrender or Peter Martin think of your budget.

Before you start changing tax rates and other policies you can plug in your own assumptions about key economic parameters, such as the level of immigration and the rate of productivity growth.

The fiscal and distributional results of your assumptions and interventions are displayed in a series of tables and charts over a 10-year time period, comparing the outcome of your budget with those of the actual budget.

The web page has a short demonstration video explaining how you can use the tool.

It’s a superb example of a model allowing policymakers and advocates to do “what if” analysis. What if the personal income tax cuts are shelved? What if productivity growth is higher than the government has assumed? And so on. Such models are valuable in that they give the user a feel for the effects of policy interventions.

No doubt the PBO has been working on this for many years with constant refinements, in order to allow them to produce estimates for parliamentarians. Making it public is a commendable initiative in fiscal openness.