Politics

Reforming political donations

Under present federal election funding laws, donations of less than $15 200 do not have to be disclosed. Total donations, and details of donations above that $15 200 threshold, have to to be reported to the Australian Election Commission but not until the October following the election, and they don’t have to be disclosed publicly until the following February.

The Parliamentary Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters has published an interim report on Conduct of the 2022 federal election and other matters. Most significantly it recommends a disclosure threshold of $1 000 and real-time disclosure. It also recommends donation caps, expenditure caps by parties and candidates, and increased public funding for parties and candidates. Two of its recommendations relate to truth in political advertising, and others relate to easing the path for people to enrol and vote as a protection against US-style voter-suppression measures.

The Coalition provides a dissenting report, mainly grizzling about Teals and other independents. It includes a number of spurious arguments against real-time disclosure, as if it is clerically troublesome. Perhaps they aren’t aware that technology has moved on since donations were made by cheque.

More interesting is a set of additional comments, well documented and carefully argued, by Kate Chaney. She puts the case for a more open and democratic election process that does not add to the benefit incumbent parties already enjoy. She lists those benefits in an appendix. Elizabeth Morison and Bill Browne of The Australia Institute have also written about the advantages of incumbency, covering the considerable financial resources sitting members have to sustain contact with their electorates, giving them a head-start in election campaigns .

The Centre for Public Integrity has “welcomed” the report, noting that it “presents an opportunity to put caps on donations and spending for the first time”: Caps needed to rein in big donors and record spending.

Writing in The Conversation Graeme Orr of the University of Queensland summarizes the report and provides some historical context to electoral funding reform: Proposed spending and donations caps may at last bring genuine reform to national election rules.

There is some way to go before we will see legislation. There are clearly partisan interests involved, and established parties have a shared interest in preserving their benefits. Also policies on political donations are fraught with unintended consequences. Orr writes:

Much needs to be thrashed out over the rest of the year. Whatever bill the government ultimately proposes to the Senate will require the Greens’ and crossbench support, or opposition backing. It is unlikely to attract the latter.

Orr seems to be ruling out the possibility of the sort of sweetheart deal that saw Labor and the Coalition uniting to pass anti-corruption legislation. But there remains the risk that the Greens and the Coalition, coming from different ideological directions, will block any reform proposals.

It’s wrong to call Donald Trump an “authoritarian”: he’s far worse.

A Washington Post article by Isaac Arnsdorf and Jeff Stein has called Donald Trump’s vision for a second term “authoritarian”, on the basis of his proposals to use extensive federal powers to combat crime, to control immigration, and to establish a civil service loyal to his agenda. In a thought process that is characteristic of Trump’s turbulent mind, he promises to “obliterate the deep state”, while extending the reach of executive government to embed a culture of muscular nationalistic conservatism.

Former Labor Secretary Robert Reich, now of the University of California Berkeley, does not disagree with Arnsdorf and Stein – they cite plenty of evidence to back up their claim – but he believes that the term “authoritarian” is an inadequate description of Trump’s political philosophy. “Fascism” is a more apt descriptor.

The word “fascist” gets thrown around rather loosely, but Reich’s post, The five elements of fascism, is carefully argued. He draws on the work of established political scientists, from whom he finds five elements that distinguish fascism from authoritarianism. Trump comes down on the fascist side on all five.

Reich finds in Trump’s statements plenty of evidence to support his classification. He could have added Trump’s behaviour in relation to state secrets. In his claim that the Democrats are out to get him he shows no understanding of the separation of the law from executive government, and he has no concept that the executive office of “president” is a role in which he was cast for four years rather than a lifelong ordination. That’s an extraordinarily muddled idea in a county that shook off the shackles of monarchy 247 years ago.

In view of his behaviour around the 2020 election, and the serious charges for which he has been indicted, it is extraordinary that Trump still commands a lead over Biden in most opinion polls, and looks certain to win the Republican nomination.

It is hard for observers of US politics to believe that the party of Abraham Lincoln and Dwight Eisenhower could be throwing its support behind Trump. Writing in The Conversation – What explains Donald Trump’s enduring appeal with Republican voters? – Jérôme Viala Gaudefroy of CY Cergy Paris Université explains that support in terms of the perverse outcomes from the first-past-the-post election system that applies in both the primaries and in the presidential election. In the primaries, because there are so many contenders, there is little chance that any one of them would have the support to beat Trump. Also in primaries, only a small number of voters, over-representative of the party’s hardliners, turn out to vote.

If by chance Trump did not win the Republican nomination, he could run as an independent, splitting the Republican vote and ensuring Biden of victory (as Ralph Nader did in 2000, splitting the Democrat vote and allowing George W Bush to take office). Even moderate Republicans, when they vote in primaries, do not want to expose themselves to that risk.

Viala Gaudefroy’s observations are a useful warning for those who believe our political parties should choose candidates purely on the votes of party members, and it is a reminder of the way preferential voting offers a line of defence against extremism.

Anti-protest laws in South Australia and other states

The most recent and most extreme laws against protests that cause obstruction have been enacted in South Australia, but there are similar laws in New South Wales, Queensland, Tasmania and Victoria.

Martyn Goddard, in his Policy Post, describes these laws and their penalties: New laws try to kill protests. Here’s why they will fail.

He believes they may be found to be unconstitutional. Drawing on experiences with similar laws in the past, he believes they may promote a political backlash when people are seen to be imprisoned for protesting peacefully to promote a public good.

Rather than prohibiting protests directly, these laws are generally drafted in terms of prohibiting the obstruction of public or business activities. He cites a Tasmanian case where the High Court has been unconvinced by such drafting, and has struck down the relevant laws. Even if a law is about obstruction rather than protest, the intent of the law counts.

On the politics of protest he goes into 200 years of history of unrest in Australia and in other countries. It is a long time since there have been mass protests against the jailing of unionists for justifiable strike action or of those who were protesting against our involvement in the Vietnam War, but we have a rich history of widespread strikes and massive demonstrations.

Behaviour in Parliament House

Some readers have drawn my attention to the political issues around Katy Gallagher’s prior knowledge of Brittany Higgins rape allegations and complaints against Senator David Van.

There was clearly a partisan element in the original accusations against Gallagher, but as The Canberra Times points out in its daily newsletter The Echidna – Gallagher saga matters little on Struggle Street –“no one looks good in this political brawl”. The article goes on to remind us “that there are young people at the centre of the issue, both of whom have been denied justice”. That was before the accusations against Van were aired.

Michelle Grattan writes in The Conversation that the Coalition seems to have kicked an own goal. In backing Lidia Thorpe and taking a swipe at Barnaby Joyce, Bridget McKenzie confirms that the issues transcend Labor-Coalition differences. (11 minutes on the ABC)

The mainstream media has given plenty of attention to the details, but there are broader issues in the whole messy situation. One relates to the culture of Parliament House, and by extension, to the way allegations of sexual assault and other bullying are handled in all workplaces, as Laura Tingle outlines in her ABC post: First Brittany Higgins, now Lidia Thorpe: Are we going backwards with how we deal with sexual harassment and assault in parliament?.

If women feel unsafe or under-respected in workplaces the cost to society is immense as women are reluctant to join the paid workforce and become over-cautious in their relationships with men. In some workplaces and institutions it appears that men and women come together not as people to work on a shared task, but as warring tribes. To some people at least, Parliament House seems to be one such institution.

Even more concerning is the way the whole fiasco plays out in the public mind, because it makes Parliament House look more like a rowdy university college than a serious institution where lawmakers come together. There are plenty of people, including the present opposition leader, who see Parliament as an impediment to government. Bad behaviour reinforces that perception.

And finally there is the issue of whether Gallagher “misled Parliament” in apparently not revealing she had knowledge of an alleged incident. Is it not misleading when ministers use every device of sophistry and statistical misrepresentation to cover up their failures or to hide their intentions? That is not to suggest two wrongs make a right, but anyone who holds information that should be kept confidential knows it is wise not to let on that they have such knowledge. That’s the advice from security agencies to diplomats and others who are entrusted with confidential information.

Polls

Voting intention – Coalition support still miserably low

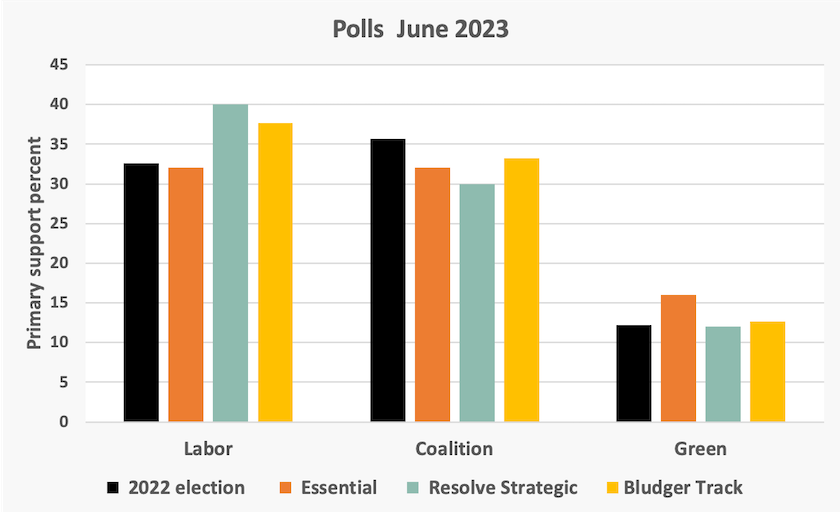

The graph below shows the latest polls from Essential, Resolve Strategic (as reported on William Bowe’s Poll Bludger), and Bowe’s Bludger Track, which incorporates and smooths data from all polls.

The Coalition’s support in 2022, at 32.6 percent, was well down on its 41.4 percent in the 2019 election. Normally after such a bad result for a political party, one would expect to see some recovery in subsequent polling, particularly when there are economic stresses of cost-of-living and housing affordability going against the government, but this has not happened: the Coalition’s support has fallen further.

Maybe this has tempted some in Labor to call for a double dissolution election, on the basis that the legislation for a Housing Australia Future Fund has twice been rejected in the Senate. But when the combined Labor-Coalition support is only somewhere between 64 and 70 percent, and when in a double dissolution a vote of 7.7 percent secures a quota, the Senate that would be elected could be very hard for a government to deal with.

Philip Lowe is less popular than Peter Dutton but Ross Gittins thinks he should stay on

The same Resolve Strategic poll reported on William Bowe’s Poll Bludger shows that only 17 percent of respondents believe Philip Lowe’s term as Reserve Bank governor should be extended. This seems to be somewhat of an ad hominem response. The RBA decisions are made by a board, not by an individual, and the real culprit seems to be the entire economics profession.

One who believes Lowe should stay on is Ross Gittins. If he were treasurer he would extend Lowe’s term so that he wouldn’t be so hell-bent on getting inflation down before his term expires in September, and so that he could observe the economic wreckage resulting from the RBA’s impatience: Maybe Lowe should stay on as governor to clean up any spilt milk.

The Essential poll asks respondents what they believe to be the factors contributing to interest rate rises. Most (62 percent) say “prices going up”, suggesting that RBA has no alternative, but 40 percent blame the RBA for over-reacting. Coalition supporters are more inclined to blame the government.

The same poll shows that most people expect there to be more interest rate rises.

Social classes

Unsurprisingly Essential finds that most Australians (79 percent) believe there are social classes in Australia. A further question reveals that half of us assign ourselves to the “middle class”, while 4 percent assign themselves to the “upper class” (up from 2 percent ten years ago). Election of a Labor government hasn’t heralded the bliss of a classless society.

Media consumption

The Essential poll asks respondents if they have changed their use of media over the last two years. As may be expected we are using newspapers and TV less, and social media and streaming services more, but the changes are not dramatic, and a significant proportion of respondents are moving away from social media and streaming services.