Other public policy

Why would anyone want to migrate to Australia?

Both the USA and Australia have an immigration policy that belongs to another era, when in the rest of the world there were “huddled masses yearning to breathe free” to quote Emma Lazarus’s poem on the Statue of Liberty.

The reality of our time is that most of the people we would like to come here are quite content to stay where they are. In the transactional language of labour economists, we are no longer in a “buyer’s market”.

Our immigration policies and practices don’t reflect that changed reality. If you have 40 minutes to spare you could listen to Mayeta Clark’s account of the woman who offers one last chance for an Australian visa on the ABC’s RN. It’s a story of what happens to the most vulnerable immigrants who are financially exploited by criminals. That’s a consequence of having an under-staffed immigration agency – a subsidiary of the Department of Home Affairs that’s more concerned with border security than with facilitating immigration – and of our having handed over much of what was once done by public servants to private immigration agents.

Andrew Giles, the Minister for Immigration, Citizenship and Multicultural Affairs, has announced a set of reforms to tackle exploitation by unscrupulous employers. Writing in The Conversation Brendan Coates, Trent Wiltshire and Tyler Reysenbach, all of the Grattan Institute, welcome the government’s plans to stamp out the exploitation of migrant workers, but they warn that those plans won’t succeed until we treat migrant exploitation like tax avoidance. The occasional penalty can simply become a cost of doing business.

Julian Assange and the US presidential election

Last week the UK’s High Court rejected Julian Assange’s appeal against extradition to the US. That leaves him with only one legal option in the UK, involving a short appeal to a panel of two judges. After that all that remains is a case to the European Court of Human Rights.

Assange’s plight came up in an interview on ABC Breakfast with Marianne Williamson, who is challenging Biden for the Democratic nomination. The 12-minute interview is a useful reminder that the Democratic Party still has a few passionate liberals in its ranks. Wilkinson is prepared to assert that American voters have been “trained to limit their political imagination”.

She said that on her first day in office she would withdrawal charges against Assange. “I believe that a free press is sacrosanct”, she said.

She had a less positive attitude towards another Australian who is prominent and influential in US politics.

What the Australian Taxation Office reveals about health policy

Last week several media sources drew attention to data made available by the Tax Office, revealing the average taxable income of Australia’s most highly paid, by occupation. Yahoo Finance, for example, draws attention to the gap between surgeons’ average income of $457 000 and the median Australian wage of $51 000. It’s a poorly-considered presentation because it compares the mean of one group with the median of another. In spite of this error, however, it carries the message that there is something seriously unequal in the rewards people get from work.

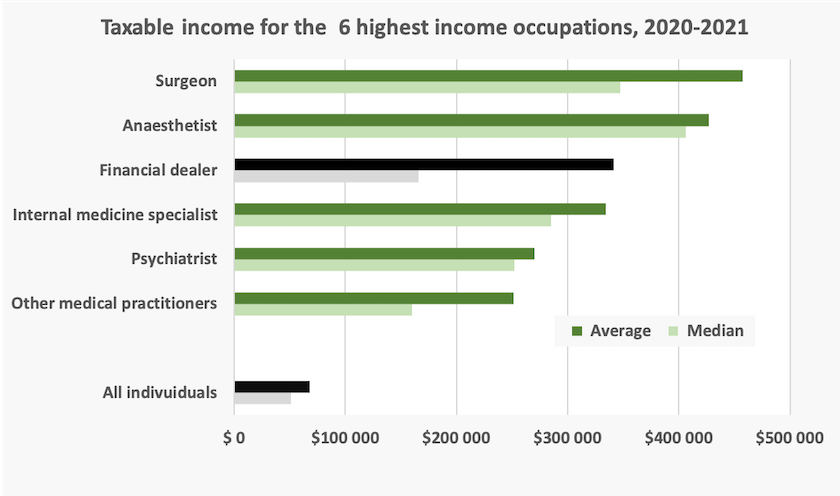

The data also reveals something about our health care system. The graph below is a re-presentation of that data from the same ATO site for the top six occupations, with the addition of median incomes alongside the average incomes.

Note that five of those six are health care professionals. The category “other medical practitioners” would contain a mixture of GPs and specialists, which probably explains the big difference between the median and average incomes: GPs are well-paid but there is a large gap between their pay and that of specialists. For specialist occupations there is less of a gap between median and average incomes, suggesting that incomes are closely clustered, as they would be if there were tacit agreements about fee levels, or if the market were so undersupplied that most specialists could charge top fees.

There is nothing in this data that would surprise any health economist. The professional colleges defend these high payments on the basis of the years of gruelling postgraduate study to gain these qualifications. But so too do university professors go through a similar process. The work of surgeons, anaesthetists and psychiatrists carries responsibility for people’s lives, but that is so for many professions, including airline pilots and engineers.

Universities and the broader community: the relationship should be stronger

On Saturday Extra Geraldine Doogue interviewed Michael Wesley, Deputy Vice-Chancellor international, University of Melbourne, about the way Australians think of universities. (18 minutes)

It’s a far-ranging discussion. Wesley believes that the relationship between universities and the broader community has soured, even though universities have made a tremendous achievement lifting the proportion of Australians with university degrees. In becoming large corporate institutions universities have lost some of their social licence, and the relationship between students and universities has become “transactional”, rather than “transformative”. Universities have come to be seen only in narrow economic terms.

They need to earn their social license again.

Diplomatically Wesley did not mention the Coalition’s “job ready” policy for universities, or its general war on scholarship and learning, but his vision for the student experience is a long way from that narrow framework. Of the university’s duty to students he says:

It ‘s about more than just imparting a particular body of knowledge. It’s about more than setting them up for a particular job. It should be about a deep form of education, making them think clearly and deeply, making them comfortable with difference and heterodox opinions and really setting them up to be critical, curious citizens of the world.“

Wesley is author of Mind of the nation: universities in Australian life.

Australia is noticed for its dealing with Nazis

One positive outcome of the ugly demonstrations by Nazis in Melbourne is legislation to ban Nazi symbols.

Those demonstrations have been noticed around the world – which is presumably what the Australian Nazis wanted. Fortunately so too has the government’s legislation. It has been a major news item on Deutsche Welle– Australia plans ban on Nazi-era swastika, SS symbol – who point out that Australia is the first English-speaking country to enact such bans, which have applied in Germany and many other countries for many years.

It is notable that Deutsche Welle’s photographs depict Melbourne’s Nazis displaying the official Australian flag – the “Australian Blue Ensign” – as their only symbol, with prominence given to the British “Union Jack” in the flag’s corner. That has echoes of the flag’s same use by racist demonstrators at the Cronulla riots in 2005.

The association of that flag with such movements lends weight to the case for our country having its own distinctly Australian flag.