Economics

Housing: it’s not complicated. We’re not building enough houses

If you want affordable housing, move to Russia.

The Visual Capitalist map of real house price movements from 2010 to 2022 shows that house prices in Russia have fallen by 33 percent over that period (possibly even more around Belgorod), while they have risen by 41 percent in Australia.

We’re not the worst: Iceland tops out at a 103 percent real price rise, closely followed by New Zealand at 97 percent. A glance at the map confirms that we share the problem with most other high-income “developed” countries.

The same is confirmed by Statista’s chart of house price to income ratios, where we come in at #13, and their chart of median house prices in large cities, where Sydney, with a median price of 11 times median income, comes in at third place behind Hong Kong and Vancouver.

Martyn Goddard, on his Policy Post, has a data-rich presentation on housing, covering the main aspects of our housing problem – homelessness, reduced public housing supply, the rental crisis, and the rise in mortgage debt. Unaffordability is the unifying theme. It’s titled Which state has the worst housing crisis?, and he provides a ranking, but no state or territory has anything to boast about.

For the most part Goddard’s post covers familiar ground, but in at least two areas he goes further than most commentators.

The first is his set of graphs on public sector dwelling approvals for each state, going back 50 years. These trace a distinct shift in public policy over that period, at different times and at different paces in different states, but all with the same outcome – a retreat from public housing. For example in New South Wales in the early 1970s each year the government was building around 10 new public sector dwellings per 10 000 population: by now that contribution is less than 1 per 10 000 population. The story in other states is similar. It’s an important point, because even though public housing may be at the lower end of the market, its contribution to supply helps contain prices throughout the whole market.

The other aspect of his work that you won’t find elsewhere is his set of estimates on the extent to which housing for short-term rental, such as Airbnb, has displaced housing available for long-term rental. He calculates that if the number of Airbnb rentals were halved, capital city rental vacancy rates would rise to levels that prevailed before there was a crisis. And that’s just Airbnb – there are other short-term rental agencies, and there are other empty houses that aren’t on any rental market. At any time around 10 percent of all dwellings are unoccupied.

He doesn’t go into solutions to make better use of unoccupied or under-occupied housing: presumably he leaves that to commentators such as the Reserve Bank Governor who suggests we might all take in a boarder. But he does advocate a temporary cap on rents, because many property owners exploit their market power to make unreasonably and unjustifiably high profits (capturing “rent” in the economic sense of the word).

Unfortunately, there has been so much talk about capping rents that the worst property owners have already raised their rents in anticipation, and temporary rent freezes tend to become long-term rent freezes, with all manner of unintended consequences. Governments are understandably reluctant to enact rent controls.

Most short-term approaches merely favour one group over another, and some such as rent subsidies, can raise prices while having no effect on supply. The solution has to come from the supply side.

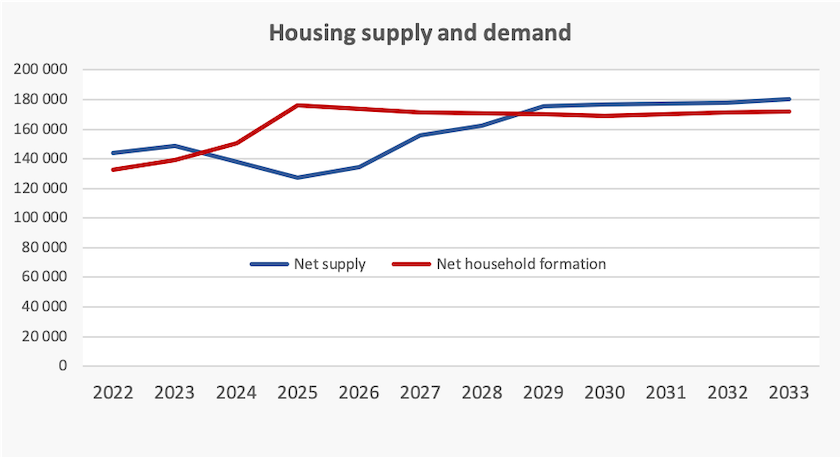

Whatever reasonable assumptions are made about immigration and average housing occupancy, any modelling of supply and demand points to a widening gap between supply and demand, accounting for the recent resumption of house price inflation and growing rental stress. The National Housing Finance and Investment Corporation, in its 2023 State of the Nation’s Housing report, forecasts that while demand will rise over the next two years, supply will fall. The graph below, constructed from figures in that report, shows that imbalance. That gap is forecast to be 12 000 in 2024 and 49 000 in 2025, before the gap slowly closes.

In short, we need a supply boost of around 60 000 in the short term.

The Commonwealth’s pathetic response has been its Housing Australia Future Fund, which is supposed to trickle out 30 000 social and affordable houses over the fund’s 5 years, drawing on the earnings from the $10 billion fund without depleting its capital.

As explained in the 20 May roundup, this approach to the housing problem is driven by accounting cosmetics, as a way to control the recorded size of government debt and to keep the budget in cash balance. Also, in trickling out the money, it is appeasing the Reserve Bank, who see any government expenditure, regardless of its purpose, as a driver of inflation.

In what must pass as one of the most excruciatingly painful media performances by a government minister, you can watch Julie Collins, Minister for Housing and Homelessness, trying to explain the government’s policyon the ABC’s 730 Report. Her miserable performance in which she keeps reverting to talking points is not her fault, nor it is the fault of the public servant who prepared her brief. It’s the fault of a fiscal culture that’s too concerned with impression management, a Reserve Bank that has lost sight of the distinction between means (monetary policy chasing the CPI) and ends (a healthy economy), and a government that’s too timid to assert the case for sound economic policy.

Mike Seccombe’s lead article in The Saturday Paper – Inside the Greens’ housing reform strategy – draws on the work of pollster Kos Samaras who warns that Labor’s weak approach to housing is an electoral liability. In spite of that, the government is digging in against the Greens’ modest compromise proposal that $2.5 billion of the fund should be spent now.

The Greens, he points out, have an economically sound suite of housing policies, including tax reforms around negative gearing and capital gains taxation. It would indeed make economic sense for the Commonwealth to allocate funds straight away to close the demand-supply gap. Because it would be an investment in an asset, it wouldn’t change the net public sector debt.[1]

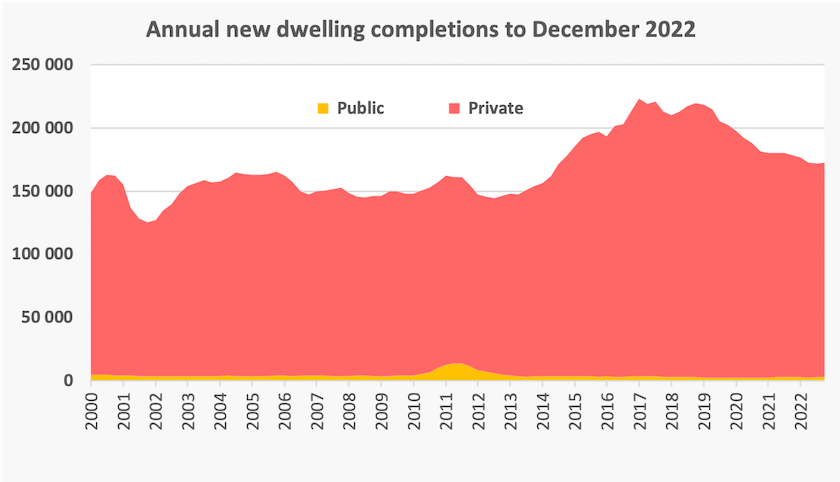

And it need not be inflationary because it would make no new call on resources. Four years ago, before the pandemic hit, we were completing about 210 000 new houses a year. By 2022 completions fell by 40 000, to around 170 000, and are forecast by the NHFIC to fall further. That fall is shown in the graph below.

The builders who were constructing those houses haven’t gone away. The resources are still there, available to be put to their best use.

Some may fear that a boost in supply would bring a reduction in house prices, but if we see commodity price inflation as undesirable, surely we should also see housing price inflation as undesirable. Furthermore, if house prices fall, those people who confuse the market price of their house with their wealth may constrain their consumption, thus achieving what the Reserve Bank has been trying to achieve with monetary policy – a tightening of money supply and a cut in spending.

1. Under Commonwealth-state funding arrangements the funds may have to be granted to state governments, meaning it would be classified as a “recurrent” outlay in the Commonwealth’s books, contributing to Commonwealth debt, but it would be an asset on states’ books. That’s one reason we need more emphasis on consolidated government accounts for all capital works. ↩

What will the government do about Stage 3 tax cuts?

The Stage 3 tax cuts are due to come into effect next year. The Australia Institute, which estimates they involve $313 billion forgone over ten years, is among the voices arguing that they should be scrapped.

By now however, the government is politically committed to go ahead with the cuts, argues Waleed Aly on the ABC’s Minefield: Are Labor’s “stage 3” tax cuts unjust and unethical?. (55 minutes)

The program is mainly a discussion about the principles of taxation, including a history of taxation, led by Aly’s co-presenter Scott Stephens. They are joined by Miranda Stewart of the University of Melbourne Law School, author of Tax and government in the 21st century, who talks about ways we could raise more taxation revenue in Australia.

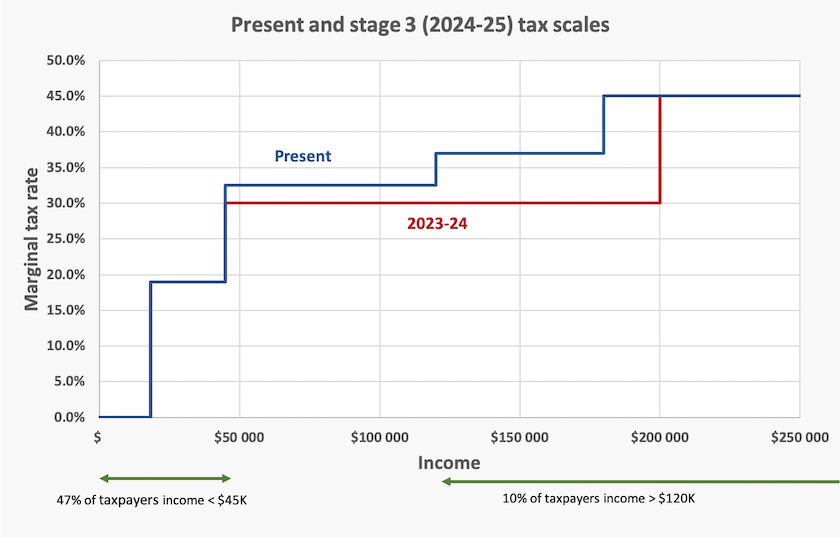

As a reminder, the chart below shows how the cuts will apply, comparing them with the existing personal tax scale.

Much attention has been paid to the shifted threshold for the top 45 percent bracket, from $180 000 to $200 000. It doesn’t look good because it will benefit only a few very well-off taxpayers, but that bracket has not been shifted for many years.

In terms of forgone revenue, the people on the Minefield panel are more concerned about abolition of the 37 percent bracket, which currently cuts in at $120 000. Our income tax scale has become flatter over the years, and that would be a further flattening.

Stewart points out that in 1950 we had 28 tax brackets, with the top bracket of 75 percent cutting in at a very high income. Now we have only 5 brackets – 4 after the stage 3 cuts – with everyone between $45 000 and $200 000 on the same marginal rate. That rate would apply to almost everyone in full-time employment.

One theme in the Minefield discussion is the evolution of community attitudes to taxation. In the early 19th century, taxation was seen as a coercion or theft – giving one’s money over to “the government”. That attitude evolved into taxation being seen as social insurance, in view of the redistributive benefits of public spending, and later to taxation being seen as a means of funding collective goods. (It’s notable that Liberal Party politicians, when they talk about “keeping more of your own money”, are echoing the idea that taxation is theft.)

The other theme is that as people age they tend to accumulate wealth, but in Australia we are heavily dependent on taxing income. We need to find ways to tax wealth, particularly the wealth accumulated by older people. That would improve a system which, in terms of intergenerational equity, is seriously out of whack.

Waleed Aly’s confidence that the government will retain the cuts is based on the political importance to Labor in keeping its pre-election promises. The other political point he could have raised is that the main beneficiaries will be people with incomes between $120 000 and $200 000. This band covers professionals and people running legitimate small businesses – the group who have been deserting the Liberal Party over the last few elections. That’s why the government is unlikely to do anything more than a few slight adjustments to the Stage 3 cuts.

National accounts reveal the consequences of the Coalition’s economic neglect

The March quarter national accounts bring home to us the consequences when a succession of Coalition governments has ignored the nation’s economic structure, concentrating instead on fiscal bookkeeping and passing that off to the community as “economic management”.

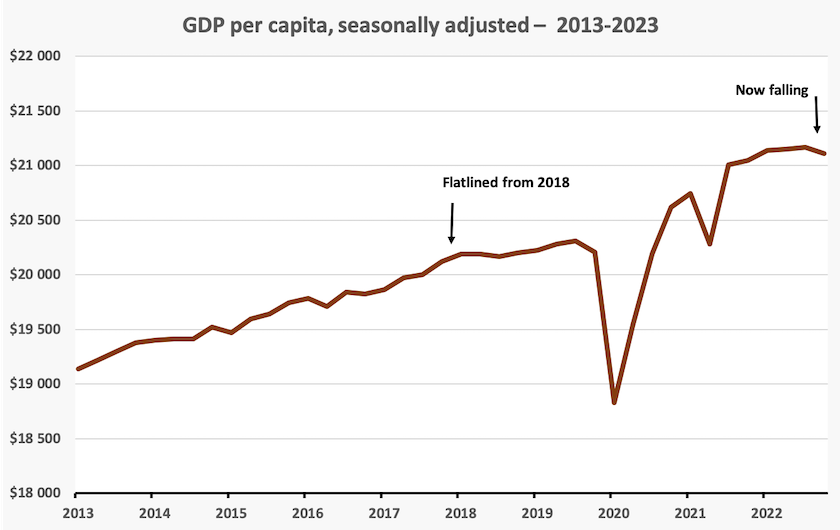

Even though the pandemic is well behind us, per capita GDP, the basic measure of people’s material welfare, is struggling to get back on track, and actually fell in the March quarter. In fact by the time the pandemic hit, per-capita GDP had been flatlining for two years.

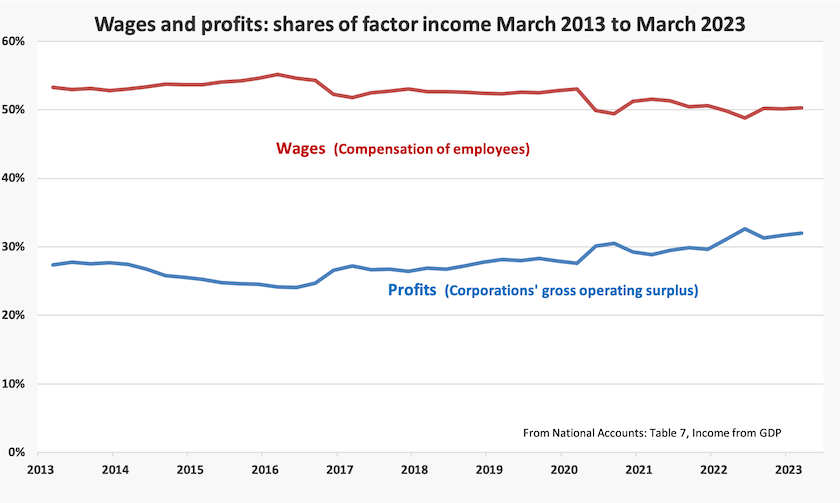

Although there has been economic growth over the last ten years, few of the benefits went to wage and salary-earners. Over that period in two distinct steps – one around 2017 and the other corresponding with the pandemic – there has been a large diversion of income from wages to profits.

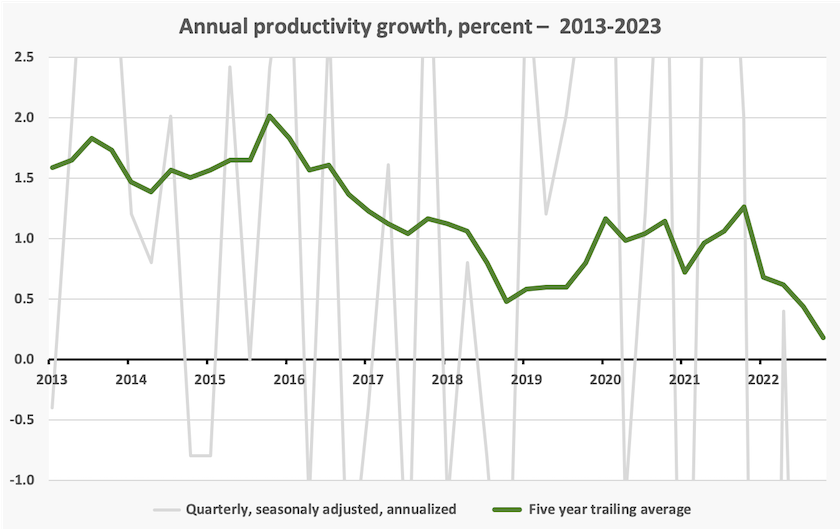

The deterioration of our economic performance can be traced largely to a fall in productivity. This fall is indicated by the national accounts data on GDP per hour worked. That figure jumps around from quarter to quarter, but its trend over ten years – generally corresponding to the Coalition’s time in office, has been downwards.

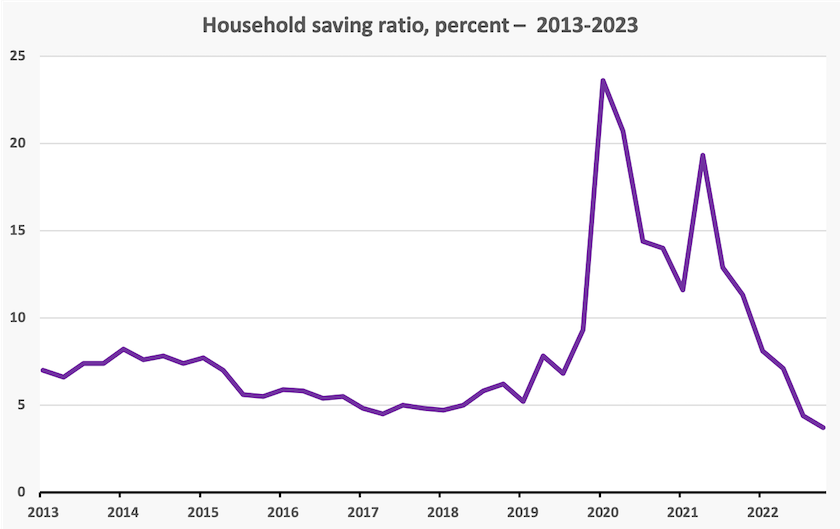

Most households have coped with falling real wages and rising interest rates by saving less. Savings are now back to pre-pandemic rates. When people have less accumulated saving to draw on they have less capacity to bear the cost of changing jobs, and are likely to resort to expensive credit products to finance spending. The beneficiaries are companies that hang on to workers who would otherwise go on to more productive work, and the finance sector selling credit and insurance. The losers are all of us.

Partisan commentators note that the deterioration in Australia’s economic performance has continued on Labor’s watch, but structural change takes time.

One promising sign in the national accounts is that there has been a significant pickup in investment in machinery and equipment – in spite of the Reserve Bank’s attempt to suppress productivity-improving investment.

John Hawkins, of the University of Canberra, presents a more comprehensive explanation of the latest national accounts, in a Conversation contribution: Going down: the 6 graphs that show Australia’s economic growth shrinking.

Profits have been driving inflation

Shane Wright, economics correspondent for The Age and the Sydney Morning Herald, has pulled together evidence from the European Central Bank, the OECD, and our own Reserve Bank, confirming that corporate profits heat up inflation.

The ECB source to which he refers is a report on the bank’s president Christine Lagarde, speaking to the EU Parliament economic committee. Referring to industries able to take advantage of supply shortages, she said “those sectors have taken advantage to push costs through entirely without squeezing on margins, and for some of them to push prices higher than just the cost push.”

The OECD Economic Outlook has a section on the contribution of profits to domestic inflationary pressures (do a search for “Box 1.2”). That section shows graphically the contribution of taxes, profits and wages to inflation in 9 countries, including Australia. In all those countries wages and profits have been pushing up inflation, but Australia (along with Spain) stands out as a country where almost all the contribution to inflation has been from profits.

The OECD stresses that “a disproportionate part of the observed increase of unit profits in 2022 came from mining and utilities: that is, mining and quarrying together with electricity, gas and water supply”. It notes that this sector accounts for only about 4 percent of the average economy but more than 40 percent of the rise of unit profits in 2022 as a whole.

A more recent observation is that Australia’s big banks have been very profitable in recent times, as revealed in the RBA’s banking indicators. Their profitability has slipped in recent years, but they’re still providing their shareholders a 10 percent return on equity, a high return for a safe industry, and because housing prices and therefore mortgage lending have risen so strongly, that return on equity has been on an expanded capital base.

The main point made by Lagarde and others is that these high profits originate from firms using their market power to charge their customers high prices, particularly buyers of energy which is such a large direct and indirect part of household consumption. Also while some corporate profits in Australia’s mining sector flow overseas, for the most part they flow into the economy as dividends and capital returns, contributing to demand-induced inflation.

Same job, different pay

In last week’s roundup we referred to the Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry’s hysteria about the rise in awards linked to minimum pay – a rise that is less than inflation for most workers. That has been followed by an equally emotive and uninformative rant about the government’s “same job, same pay” industrial relations changes. To read the ACCI’s press release one would believe that employers will be prohibited from offering higher pay for workers who have more experience or who are more productive.

In fact, as explained by Gemma Beale of Flinders University, writing in The Conversation, the main purpose of the government’s changes is to prevent companies from circumventing provisions of pay and conditions that they have negotiated with their own workforces, by using labour-hire businesses to replace those workers. She writes that “the bill is part of an election promise Labor made to address instances of employers using labour-hire firms to deliberately undercut the wages and conditions they offer in enterprise agreements”: Business is trying to scare us about ‘same job, same pay’. But the proposal isn’t scary.

Writing in The Saturday Paper – Big business attacks wages and workers – Paul Bongiorno explains that business lobbies, with help from the Murdoch media, are presenting the government’s reforms as an assault on the nation’s prosperity. There are echoes of the campaign conducted by the same interests against the Rudd government’s Minerals Resource Rent Tax. The strategy is to concoct a wages policy that the government has no intention of implementing, and launching a multimillion-dollar campaign against it. Bongiorno writes:

What this whole farrago demonstrates is how desperate the business and industry groups are to maintain the imbalance of the past 10 years or more, which have seen record profits while wages have stagnated and gone backwards.

The problem for public policy is that some well-funded and noisy lobby groups, who claim to speak for “business interests” (whatever they are), are attached to a nineteenth century model of the economy as a struggle between “employers” – a virtuous and enterprising class of people – and “employees” – a greedy class of people sucking the economic system dry. Marx would have recognized the division, while disagreeing vehemently with the description of the classes.

Those who have invested so much in this model find it hard to understand a more liberal economic model where people with different resources – finance, qualifications, experience, energy, industry-specific skills, creativity – come together to create value and to share in returns from those contributions. That’s the economic model that fosters productivity and sustains long-term prosperity.

More on productivity: it’s not just arithmetic

The Reserve Bank has some weird ideas on productivity, such as the idea that higher interest rates will lift productivity, when in effect the bank’s decisions to raise interest rates discourage productivity-improving capital investment.

Even if the bank’s board doesn’t realize that their monetary policy decisions are suppressing productivity, they have certainly enlivened the debate. Productivity was a strong theme in Governor Lowe’s address at the Morgan Stanley Summit on June 7, the day after the board had once again decided to lift interest rates.

Monetary policy and fiscal policy shape the macroeconomic environment, and if those policies are purely focussed on indicators such as the CPI or the budget cash deficit, they may do little to advance productivity, or even set it back, as seems to have been the case in Australia in recent years.

Policies on taxation, education, infrastructure, training, competition and immigration, in that they shape resource allocation, can improve productivity if they are well-designed.

Public policy, however, can go only so far. Two contributions, one from the Committee for Economic Development Australia (CEDA) and one from Assistant Minister for Competition, Charities, Treasury and Employment, Andrew Leigh, provide practical advice for enterprises.

CEDA’s advice to enterprises concerned with efficiency

“More firms need to prioritise innovation over efficiency”

That’s a quote from the CEDA report Dynamic capabilities: how Australian firms can survive and thrive in uncertain times, a guide to how Australian enterprises can lift productivity.

The idea that firms should relegate efficiency to second place sounds almost heretical. Isn’t productivity about doing more with less, and isn’t that what efficiency is all about?

That’s all very well – firms should do what they do efficiently. But more importantly what counts are what the authors call “dynamic capabilities”. They write “firms can be better or worse at identifying new opportunities, managing competitive threats, using their resources and making necessary transformations”.

There are business school case studies about firms that became the world’s lowest-cost producers of electric-mechanical typewriters or film cameras, oblivious to the emergence of other technologies. In the service sector firms and organizations use routines and finessed operating procedures, missing opportunities to adapt those services to customers’ and clients’ needs. Productivity isn’t just about technical efficiency: in its broadest sense it’s about using scarce resources in ways that can best contribute to human well-being.

CEDA’s report comes across a little like a sermon from the pulpit of the Harvard Business School, with too much use of managementspeak words such as “strategic” and “dynamic”, but it is based on solid research and carries an important message for enterprises that put all their energies into cost-reduction without looking around at the wider world.

Andrew Leigh’s advice to anyone with a computer or cellphone

A productive workplace is one where machines are reliable and easy to use, and where people can work without distraction. This applies as much in a bank, public service department or a school, as it does in a trucking terminal or a manufacturing firm.

In an interview on the ABC’s Saturday Extra (just before he leaves to travel to South Africa to take part in an ultra-marathon) Andrew Leigh asks are pointless emails and social media linked to poor productivity?. (13 minutes) These tools are supposed to improve our productivity by making for more efficient communication, but a workday punctuated with interruptions is not conducive to the sort of work that requires concentration and intense engagement with a task – “deep work” in Leigh’s terms.