Economics

The Reserve Bank’s dangerous obsession

In raising the cash rate target by 25 basis points to 4.10 percent the Reserve Bank board confirmed that it will pursue its mission to bring down the CPI – an indicator of inflation – regardless of the damage it may impose on the economy.

The substance of its thinking is in the second paragraph of its media release (the rest could have been written by AI):

Inflation in Australia has passed its peak, but at 7 per cent is still too high and it will be some time yet before it is back in the target range.

If inflation has passed its peak, and is on its way back to its target range (2 to 3 percent), the threat of runaway or accelerating inflation has passed. Without further meddling with interest rates, inflation would come down. But the RBA wants to rush the process.

Why?

Peter Martin, in his weekly Conversation contribution – Why Reserve Bank Governor Philip Lowe wants to damage the economy further – hints that Lowe might be seeking to get inflation near the RBA’s target zone before he retires in September. The more likely explanation, Martin explains, is that the RBA, in weakening the economy, wants to contain the bargaining power of workers. It seems to be upset that Australia’s lowest-paid workers have suffered only a one percent cut in real wages: they’re not suffering enough.

National accounts for the March quarter 2023, published on Wednesday, confirmed that the economy has taken a battering. GDP per capita has fallen (that’s recession territory), household savings are depleted, and productivity is negative. The RBA board knew the national accounts were due (the ABS has a rigid schedule). That would have been a good reason to hold off for June. But they had to go ahead, obsessed by that CPI number. Were they worried that poor national accounts data would weaken their case for an interest rate rise.?

More worrying than the RBA’s haste is its assertion that inflation is 7 percent. That statement is entirely unsupported: if a first-year economics student wrote that as a statement about current inflation, they would earn a fail grade, but the RBA asserts it without qualification.

All that can be said is that between March 2022 and March 2023 the Consumer Price Index rose by 7.0 percent. That is its change over twelve months. But in fact over that 12 months the CPI was growing more slowly. The data is between three and fifteen months old, and is heavily weighted by price rises early in that period.

The rise in the CPI in the March quarter this year was 1.4 percent, which corresponds to an annual rate of 5.7 percent, not 7.0 percent as the RBA asserts. The ABS “trimmed mean” CPI rise for the quarter – a figure that excludes extreme movements – was only 1.2 percent, or 4.8 percent annualized.

To explain it another way, if you had taken three hours to drive from Sydney to Canberra, a distance of 300 km, keeping to the 110 kph speed limit on the freeways, and were now travelling at 50 kph in a Canberra suburban street as you neared your destination, you would be rather peeved if a cop booked you because your average speed over the trip was 100 kph, in excess of the 50 kph speed limit in the suburban street. That’s how basic the RBA’s misrepresentation of the data is.

That is not to assert that the RBA should have said that inflation is 4.8 percent, but that would be more justifiable than saying it’s 7 percent. Any figure it uses should be highly qualified, because no one knows what inflation is now.

In fact in using that high estimate of 7 percent, the RBA is reinforcing the idea that inflation is high, driving justifications for high price increases and wage bids.

It’s as if the RBA has a vested interest in overstating inflation so that it can justify using its big and slow-acting lever, inflicting misery on millions of Australians who have to bear the cost of the board’s obsession. Even if that’s not its intention, it’s irresponsible for the RBA to be shouting from the rooftops that inflation is seven percent, when there is strong evidence that it’s significantly lower. Governor Lowe and the Board know that suppressing inflation is largely about quelling inflationary expectations. Why are they fuelling those expectations with a high number?

In any event it is incorrect for the RBA to use the CPI as an unqualified statement of “inflation”. The CPI is an indicator of changes of the cost of living for a representative urban household, which, in the short term, can be very different from general price movements in the economy. But there is no such qualification in the bank’s statements.

Those who wrote the Governor’s statement would know this: they are some of the nation’s most well-qualified economists.

So why is the board deliberately using such patronizing and misleading language to explain its decisions?

Fear and loathing as the lowest-paid workers get a partial wage relief

On Friday the Fair Work Commission awarded a 5.75 percent increase in minimum wages for around a quarter of Australian employees.

To read the reaction of the Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry one would believe that Bolsheviks and barbarians have mounted an attack on capitalism, “unlocking the floodgates for deep and prolonged economic pain”. It is “a hammer blow for the 260,000 small and family-owned businesses who pay minimum and award wages” and is “inflicting pain on families and small business”.

The Australian Industry Group is less critical. They “recognise the competing tensions involved between addressing cost of living pressures and the difficulties of a large increase in a weakening economy including for the many small and medium-sized businesses who are also doing it tough”.

Both groups warn about the macroeconomic consequences of this rise, but are they significant? According to the Fair Work Commission, because the 5.75 percent rise is only for the lowest-paid workers, it applies to only 11 percent of the employed workforce. That amounts to about 0.6 percent of the national wage bill or less than 0.3 percent of GDP.

Business cries poor on wages, even as profits mount is the headline of Ross Gittins’ post in reaction to the Commission’s decision. He goes on to note that the Reserve Bank, in its obsession with wage growth as a source of inflation, has come down on the side of the business lobbies.

The use of emotive language about “families” and “small business” doesn’t help us understand the realities of the Australian economy. That language makes us think of the struggling sole trader – the painter with a beat-up van seeking work so he can put food on his family’s table, the immigrant owner of a coffee shop who lost her custom when the pandemic hit, the farmer battling the climate and rigged livestock markets. In fact they are largely unaffected by wage rises: they decide how much wage to pay themselves from their businesses.

But for the most part the family-owned enterprises that the ABS and others classify as “small business” are doing rather well. The people who use family trusts and elaborate businesses structures to avoid paying taxation, who claim luxury cars and foreign travel as business expenses, who use labour-hire companies to separate themselves from moral responsibility to their employees, and who enjoy favourable anti-competitive regulations as a result of political lobbying, are also part of the “small business” community.

It is notable that, apart from a very small group – 0.7 percent of employees – the 5.75 percent increase does not compensate for the 7.0 percent rise in the CPI over the year to March: it is actually a 1.25 percent cut in real wages. The Commission acknowledges as much, while arguing that it is “the most that can be justified in the current economic circumstances”. It explains its principles in the most unobjectionable language of mainstream economics:

In the medium to long term, it is desirable that modern award minimum wages maintain their real value and increase in line with the trend rate of national productivity growth.

HECS-HELP debt – surface manifestations of deeper problems

On June 1 more than 3 million Australians saw the outstanding balance on their student debt rise by 7.0 percent, in line with the rise in the CPI over the 12 months to March.

Student debt is a growing burden on young people. The financial firm Futurity Investments quantifies that burden in its report The financial and social impact of the cost of university education, noting, for example, that 61 percent of graduates aged 22 to 29 have finished university with a HECS-HELP debt between $20 000 and $50 000. These are substantial amounts for people who, having deferred an opportunity to earn a decent income, find themselves facing a brutally overpriced housing market.

Some politicians, including the Greens, suggest abolishing or deferring indexation of debt, but that would be a quick fix, rather than a solution based on principles of equity or economic efficiency. More realistically Jane Body of Think Forward (an organization advocating for intergenerational fairness), who herself is carrying $78 000 student debt, calls for indexation in line with average wages growth: Jane doesn't expect to pay off her student debt until she's 65. Could the system be fairer? on SBS.

Such solutions would offer some relief, but they don’t confront the more critical issue of tertiary education funding – university funding in particular.

Rick Morton raises these broader issues in his Saturday Paper contribution: Huge rises in student HECS debt, which is about the damage done to our universities by the Coalition’s 9-yearwar on learning and scholarship, topped off by its sloppily-designed “Jobs-ready graduates package” that worked against its own claimed outcomes. Morton gets to the basis of the problem where he refers to “the corporatisation of higher education institutions and the degradation of academic qualities”.

In the late nineteenth century the Australian colonies adopted the norm that education should be compulsory and taxpayer-funded for young people up to age 14. There was progress through the twentieth century as longer school attendance became the norm. The Curtin government expanded the availability of university scholarships and the Menzies government boosted the Commonwealth scholarship scheme further. Then the Whitlam government abolished university fees altogether in 1974.

That was the high point. In the late 1980s the Hawke-Keating government backtracked, and introduced the HECS scheme. The fee was modest – $1800 per year (equivalent to about $4000 now) but as with Medicare, the then Labor government was quietly abandoning its principle of universalism in health and education and its commitment to a social wage. The way was open for subsequent governments to require higher levels of student contribution and to lower the threshold for repayment of student debt. This also aligned with the Coalition’s obsession with government debt: shifting education debt off the government’s ledger and on to graduates was one of its techniques of fiscal impression management. The Parliamentary Library has a chronology of higher education loan programs from 1989 to 2021.

There is a strong case in equity and economic efficiency for abolition of university fees: many countries have free or nearly-free universities. As tertiary education has become more widespread, the personal income premium enjoyed by graduates has diminished, but the community benefits of a well-educated population are unabated.

In 1989 when HECS was introduced, graduates were still enjoying a significant income premium: HECS looked like a good idea at the time. Also productivity was high, which meant that as with other workers, graduates’ incomes would rise more quickly than inflation. Indexation looked like a generous offer.

Now, 34 years later, the landscape is different. Over those 34 years governments – mainly Coalition governments – have failed to pursue policies to improve our economic structure and consequently productivity has stalled. When nominal incomes are rising more slowly than inflation, a loan indexed to inflation becomes an increasing real liability. That wasn’t the way the HECS designers saw it in 1989.

Moreover, not only has the income premium enjoyed by all graduates fallen (the general working of demand and supply), but also the pay for teachers and nurses has been even more constrained. That is because most are employed by state governments, or in establishments such as Catholic schools that match government pay. They are paying the burden of fiscal austerity. It is hardly surprising that the Futurity research found that “university educated females have more HECS-HELP debt and earn less than their male contemporaries”. And it’s hardly surprising that there are shortages of teachers and health-care workers.

The student debt problem is a manifestation of a much deeper problem in university funding, weakening our ability to provide school education and healthcare. This problem is aggravated by the government’s reluctance to collect enough taxation to fund necessary public goods. Tinkering with HECS-HELP indexation won’t fix it.

Productivity – the hard numbers and beyond

It is possible to make two strong statements on productivity, one supported by the basic logic of economics, the other by observation. Between them they explain why for many Australians their real incomes are falling.

The first is that without improvement in labour productivity there cannot be any sustained real wage growth.

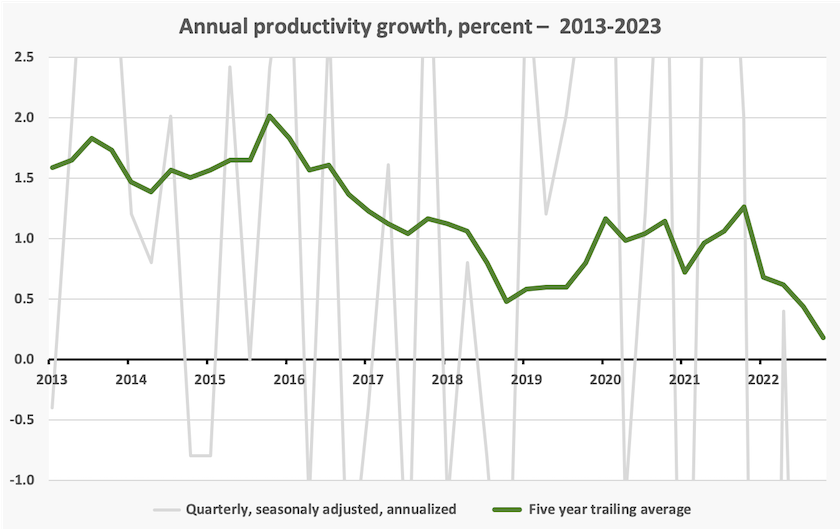

The second is an observation, revealed in national accounts, that labour productivity has been falling since the turn of the century.

Of course it’s a bit more complicated, but not much. There are many ways to measure labour productivity – GDP per hour worked, per employed worker, per adult and so on. There are problems in measuring productivity in the public sector. Indicators of productivity can swing with our terms of trade. But they all point in the same direction. As Joseph Stiglitz stated “productivity isn’t everything, but in the long run, it’s almosteverything”.

The most common economy-wide indicator of productivity, GDP per hour worked, is shown in the graph below. Don’t get too excited about that jump in 2021: “Jobkeeper” did strange things with our figures, and as a general rule when hours worked fall, as they did during the pandemic, output per hour rises. The trend is downwards.

In his Saturday Paper contribution – The productivity collapse – John Hewson has a prospective look at productivity. He is pleased to see that the government is serious about productivity in a way that the previous administration was not. The source of productivity gains will be through innovation and investment in industry restructuring:

It will be crucial to link the national productivity strategy with the government’s new policies to rejuvenate manufacturing and, most importantly, with the proposed work of the new Net Zero Authority.

We should also remember that while there can be no gain in real wages without improved productivity, the syllogism does not invert. If all the gains in productivity go to profits, in businesses small and large, there will still be no gains in real wages.

If workers believe the system is stacked against them, they won’t bother, and no one will benefit because without worker cooperation it is hard for any business to improve productivity.

Hewson quotes Alan Kohler’s New Daily article: Productivity has collapsed because workers have lost hope, a comment on our decline in productivity growth: “The reason labour productivity (GDP per hours worked) has been flatlining is because workers don’t care any more”. Kohler goes on to write:

It seems to me that workers in almost every industry are jaded and disengaged – they’re being forced to work harder and be a jolly part of a team culture, with team leaders instead of bosses, and expected to be happy with pay rises of 2 to 3 per cent, if that.

Domestic aviation: you’re better off driving

Imagine that you live in Melbourne and have an important appointment in Sydney – a job interview, presentation for a tender, a connection to an overseas flight, a wedding or a funeral in which you have a role. Knowing that 9 percent of flights on that route are cancelled would not fill you with confidence. And even if your flight isn’t cancelled, you would not be reassured by the knowledge that only 72 percent of flights arrive on time: that is, within 15 minutes of their scheduled arrival time.

Assured of a place to land

Those are some of the figures from the ACCC’s document Airline competition in Australia –June 2023 report. Even though the cost of kerosene has fallen, fare prices remain above pre-pandemic levels. Sydney is the worst-performing large airport, but over Australia as a whole 4 percent of all flights are cancelled.

The ACCC’s findings relate mainly to domestic services. It also notes that there are similar, but less severe, problems in international aviation.

The ACCC attributes the industry’s problems mostly to a lack of competition:

The duopoly market structure of the domestic airline industry has made it one of the most highly concentrated industries in Australia, other than natural monopolies. The lack of effective competition over the last decade has resulted in underwhelming outcomes for consumers in terms of airfares, reliability of services and customer service.

The ACCC hopes there will be more competition if Rex and Bonza can expand their operations, but new entrants face impediments in gaining access to large airports because slots have been issued in perpetuity to the large domestic carriers.

They also call for better means of consumer redress when passengers are let down.

Apart from a few figures on the price of airfares, the ACCC does not estimate the total economic cost of poor airline performance. Such an estimate should include the costs incurred when people take precautions in case of unreliability – driving instead of flying, and allowing a large buffer or even the extra cost of overnight accommodation to be sure of being on time for an appointment. Nor does the ACCC estimate the opportunity cost of travel not undertaken because airlines are too unreliable.

The ACCC’s solution is predictably along its single track – more competition within aviation. But we’ve been there with third airlines, most notably Compass Airlines in the early 1980s, which ran afoul of the then prevailing two-airline policy. Many aspects of the policy remain to this day, such as access to slots. And even from a strong market position Ansett failed in 2002.

True competition would be provided by a proper train service around the east coast and on to Adelaide. In view of the high unreliability of airlines a train service could command premium prices, as is the case in Europe, leaving airlines as the fallback for budget travellers. If evaluations of fast train services considered all the consumer costs of flying, and applied them to the price of train fares, the benefit-cost ratios for a fast train service would surely look attractive.

How to spot an autocrat’s economic lies: climb a hill at night

There is a story about an IMF official visiting an unnamed banana republic. On the evening he arrived he was met by the head of the country’s economic ministry. The road to the city centre was poorly-lit, but on the way he noticed an industrial plant with lights blazing and a row of delivery vans coming and going. He asked his host what the enterprise was.

It was the country’s note-printing works, working 24/7 to keep up with the country’s soaring inflation.

Lights tell an economic story. Writing in Foreign Affairs –How to spot an autocrat’s economic lies – Luiz Martinez of the University of Chicago reports on his research in which he compared countries’ official GDP and the spread of nighttime lights recorded by satellites. It sounds fanciful but it checks out with other estimates of the extent to which governments in countries with authoritarian regimes overstate their economic performance. His research debunks the theory that autocracies tend to enjoy higher rates of economic growth than democracies – a common rationalization for those who defend authoritarian governments.

His work is also a reminder that one of the most important institutions in a country is its statistical agency, which should be at a long arm’s length from executive government. Governments may fiddle with the appropriations for our ABS, but it is structurally well separated from executive government, and its independence is supported by a strong professional management culture.