The budget

Fiscal stuff – a budget that John Howard might have presented

As statements of economic policy government budgets are overrated.

Policies on industry regulation, immigration, and trade, involving little or no budgetary appropriation, are more economically consequential in the long run than the budget. The budget is simply a bill to allow the government to appropriate money for certain purposes, mostly involving a continuation of existing programs.

Within the budget, the size of the cash surplus or deficit, which captures so much media attention, is of minor consequence. In round numbers the government is spending about $600 billion and collecting about $600 billion. A $4 billion surplus, about which the Treasurer is crowing, is the difference between two uncertain quantities, dwarfed by errors of estimate in revenue and expenditure.

In any case the cash surplus or deficit, in itself, is pretty meaningless in economic terms. To pass any judgement we need to know how that $600 billion will be spent – on recurrent outlays including distributive welfare and boondoggles and favours for the government’s political mates, or investments in education and infrastructure that will ensure ongoing prosperity? Similarly we need to know how that revenue is collected – through a taxation system that favours short-term asset speculation (as has been the bias in the tax system inherited from the Coalition), or one that encourages structural change to improve the productivity of our industries?

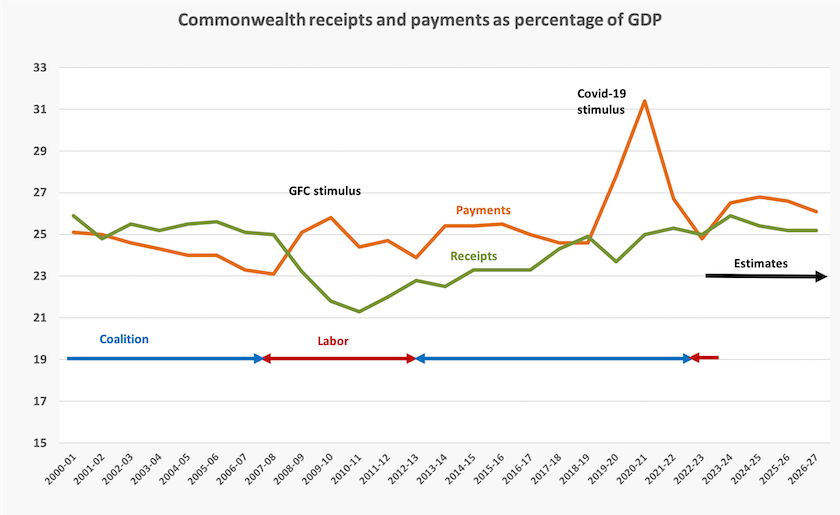

The government’s fiscal policy is most easily presented in one graph, showing receipts and outlays over this century so far, taken directly from the historical data in Budget Paper 1.

On the spending side this shows the rundown during the Howard administration, the boost in response to the global financial crisis in 2008, and the more recent (and much higher) boost during the pandemic.

Going back to 1929, Labor has generally been in office when external developments have dictated the need for a large fiscal boost, and a corresponding increase in the budget deficit. In this regard it is interesting to speculate on what the Murdoch media would have said about the pandemic spending boost had Labor been in office at the time. This time the need for a fiscal boost, the most significant in 50 years, was on the Coalition’s watch.

Receipts, mainly from Commonwealth taxation, have generally been rising since the GFC, apart from a small dip during the pandemic.[1]

Going forward it is notable that there is estimated to be an ongoing gap between payments and receipts. This is what has come to be called the “structural” deficit.[2] The expected downturn in spending is significant.

More notable is that this expected downturn in spending is in 2025-26 and 2026-27, the years after which the government would be hoping to enjoy its second term in office. There are some savage real cuts in these outer years, revealed in Statement 6: Expenses and Net Capital Investment in Budget Paper 1. Water reform, the arts and cultural heritage, environmental protection, road and rail transport, and urban and regional development are all facing cuts. There are also predicted cuts in most programs’ expenditure on administration, presumably reflecting savings from reduced employment of consultants and contractors.

This is the budget of a government that is still pursuing the Howard administration’s “small government” agenda. Ignoring the pandemic jump, spending is only a little higher than in previous administrations. Spending growth is generally driven by demographic factors rather than by new programs.[3] Taxation revenue is forecast to stabilize at the level it reached during the Howard administration.

We can over-analyze budget figures, however. Fiscal projections are only as good as the assumptions on which they are based. No government has a good track record in its fiscal forecasts: forecasts of spending tend to be a little more robust than forecasts of revenue, but both are shaky. Ross Gittins casts his sceptical eye over fiscal projections in his post: Debt and deficit fixed in just Labor’s second budget. Really?

The government will defend its austerity by reference to the debt it inherited: they love talking about that “one trillion dollar” gross debt, even though, in comparison with most other prosperous countries, our general government debt is quite modest. There is room for public investment to restore our impoverished public services, particularly education and infrastructure. The Albanese government is forgoing this opportunity, presumably in the interest of being seen as the better economic managers in public judgement, a judgment based on simple fiscal numbers rather than on economic policies.

This budget keeps Australia in the same “small government” camp as the USA. In comparison with other prosperous countries our public spending, as a proportion of GDP, is at least 5 to 7 percent of GDP lower than in high-income European countries.

A nation’s prosperity depends on an appropriate mix of public and private goods and services, but our public sector is probably well below the optimum size. Unless this, or a future administration more attuned to social-democratic values, increases public spending and revenue, we are likely to remain a country suffering from what JK Galbraith called public squalor amid private affluence, forgoing opportunities to improve our economic prosperity.

1. About 7 percent of receipts are non-taxation, mainly from government financial investments, including the Future Fund. ↩

2. A recently coined term, confusing because it has nothing to do with the more significant issue of the nation’s economic structure. ↩

3. Spending is estimated to reach a maximum of 26.8 percent of GDP in 2024-25. The previous high point was 27.5 percent in 1984-85, before Treasurer Keating applied the brakes. ↩

Economic stuff – at last a statement on economic structure

The budget includes the usual statement about economic outlook – Statement 2: Economic outlook in Budget Paper 1. It presents a gloomy short-term outlook for the world economy, but with some optimism about inflation and interest rates peaking soon, and supply chain problems easing.

In comparison with other “developed” countries Australia’s economic prospects are reasonably bright. Real wages are expected to start improving over the next twelve months, but our terms of trade will deteriorate. Importantly, non-mining business investment is expected to rise. Overall the outlook for the Australian economy is little changed from that provided in the October 2022 budget.

A concise summary of the budget’s economic statement, with some fiscal implications, is provided by Peter Martin in a Conversation contribution: Budget 2023: budgeting for difficult times is hard – just ask Chalmers.

For the first time this budget includes a statement on economic structure – Statement 4: Structural Shifts Shaping the Economy in Budget Paper 1. To quote from its introduction, it describes three structural concerns:

… the growing care and support economy; our expanding use of data and digital technology; and climate change and the net-zero transformation. Harnessing the opportunities that come with these transitions, whilst effectively managing the challenges, is critical to our future economic performance and prosperity.

The statement recognizes the care and support economy, particularly how its importance will grow as the population ages, and it assesses the demands it will place on our workforce and public budgets.

In public administration circles the care and support economy has largely been seen as a costly overhead. But it is no less responsible for our well-being than other sectors – manufacturing, mining, agriculture and so on. This recognition means that public policy should be more attentive to the sector’s productivity, which has been hampered by inadequate use of information technology and restrictive practices, and to the sector’s need for a trained and educated workforce. Until we attend to that need we will be heavily dependent on immigration, in a world where many countries are bidding for the same workers.

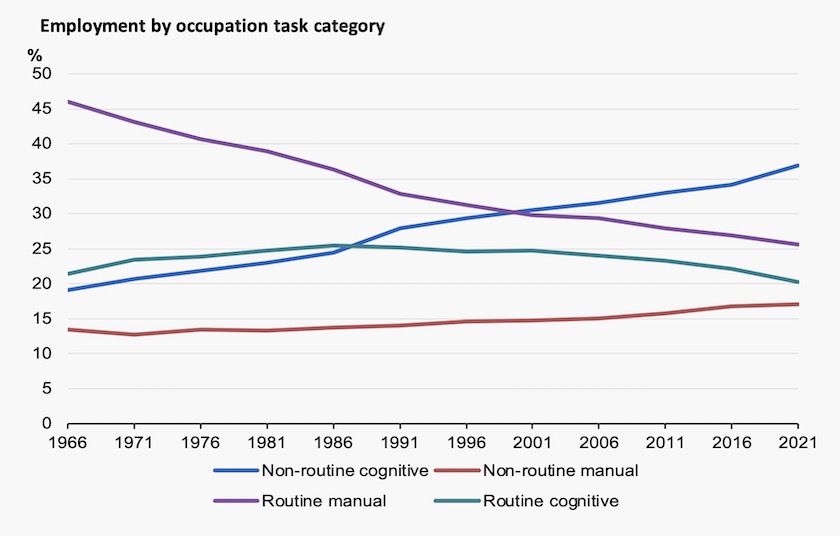

The most telling message in the statement is about the changing nature of employment. For a long time there has been talk about manufacturing jobs giving way to service jobs, and unskilled jobs giving way to skilled jobs, but these categories are vague and not very descriptive of what is actually happening. This paper uses a 2 X 2 classification identifying jobs as “manual” or “cognitive” and as “routine” or “non-routine”.

The long-term trends in these classifications are shown in the diagram below, copied from the budget paper. We are all familiar with the long-term decline in “routine manual” jobs: assembly-line jobs are the prime example. Over the last 30 years there has also been a decline in “routine cognitive” jobs: bank tellers and account clerks come to mind. At the same time there is growth in “non-routine manual” jobs, including jobs such as cleaners and waiters. But the biggest rise has been in “non-routine cognitive” jobs.

These trends have implications for our training, education and immigration policies. The decline in routine jobs means that there should be more emphasis on adaptability and a capacity for lifelong learning, and a recognition that specific skills can rapidly depreciate in value. The idea of a trade-off between a liberal education and a skills-specific education is a false dichotomy. We need both, because the liberally-educated worker understands the need for adaptability and lifelong learning. An example of that need is the changing work of auto mechanics as electric vehicles displace IC vehicles.

The ABC’s Gareth Hutchens has a summary of this statement on structural adjustment: Care workers, climate change, and personal data. The budget says they're steering our economy. It’s a pity that he, and other journalists who understand that economic management is about far more than managing the fiscal numbers, was not providing the ABC’s immediate media commentary on the budget. Most of that coverage was by generalist political journalists with little understanding of economics.

This recognition of the importance of economic structure is not new: during the Hawke-Keating administration structural adjustment was at the core of economic policy, driving a major economic transformation. But in the following quarter-century, a period dominated by Coalition governments, structural adjustment was off the government agenda. At first the excuse for this neglect was “reform fatigue”. This gave way to an era of slothful administration where the main concern of policymakers was to protect established industries from structural change, while the finance sector and other rent-seekers creamed off the declining surplus.

The Coalition’s response – it’s hard to criticize a budget Frydenberg could have presented

The government’s conservatism left Peter Dutton and his staff with a hard task in preparing a budget in replyspeech.[4] He had little political choice but to support many of the government’s measures, and to try to blame the government for inflation, particularly in power prices, and for the resumption of immigration which will add to stress on housing markets.

Writing in The Conversation John Hawkins, of the University of Canberra, makes it clear that the budget will not contribute to inflation: No, the budget does not make further interest rate rises more likely. Any inflationary impact from increased social security transfers is likely to be trivial, and would be more than offset by measures that will see the medical and energy components of the CPI fall.

One budget measure that could result in a small but widespread rise in prices is the government’s decision to raise the heavy vehicle road user charge in increments of six percent over the next three years. Truckies are grizzling, but it’s a competitive industry, and that charge will generally be passed on in prices of most goods. Should that price rise be treated as “inflation”, however? It is simply an adjustment in prices, because an industry that has been heavily subsidized and has been damaging our roads is now required to pay its way. This price adjustment will contribute to a better allocation of resources if it provides funds to repair damaged roads and gives some disincentive for goods to be trucked over long distances rather than supplied locally.

As for immigration, it is simply resuming its pre-pandemic trend, but, as pointed out in the budget’s economic outlook “total net overseas migration is not expected to catch up to the level forecast prior to the pandemic until 2029–30”.

The most outrageous aspect of Dutton’s speech is early on where he states “the budget is a missed opportunity for economic structural reform”.

The Coalition, in office for all but six years between 1996 and 2022, did hardly anything about structural reform, other than making the Reserve Bank independent and introducing the GST. Otherwise its approach was worse than neglect: it deliberately thwarted structural reform in the energy sector, which is the main reason power prices today are much higher than they should be. It was on the Coalition’s watch that labor productivity declined, which is why real wages have been falling: in fact the Coalition saw low wages as a desirable economic outcome.

OK, hypocrisy is normal political practice, but the most disappointing aspect of Dutton’s reply is his reliance on the tired Liberal Party “small government” mantra: “we believe in lower taxes to allow Australians who work hard to keep more of their own money”.

A long period of “small government” is why we have an under-educated workforce, why our transport system is inadequate for an advanced economy, why non-mining investment has been sluggish, why we are carrying the burden of a bloated finance sector, and why our health care system is struggling. As for the claim about the Coalition’s policies allowing people to keep more of their own money, that’s an outright lie: what people save in taxes paid to governments is more than offset by what they have to pay to privatized tax collectors – from toll road companies through to private health insurers.

A more lively, though somewhat overstated, reply to Labor’s timid budget is in a collection of statements made by Greens Members of Parliament: Labor’s budget keeps people in poverty, while the wealthy and big corporations win big.

4. That link is to a transcript. If you seek the theatrical pleasure of seeing Dutton present his speech there is a YouTube video presentation of the speech. ↩

A panel of economists – positive assessment, but it could have been more generous

The Conversation reports on the views of 57 economists. On a scale A to F, two thirds give the budget an A or B, a much higher assessment than the same panel gave the most recent Coalition budgets. Those who mark it down generally do so because they believe it should have done more to help the unemployed and those suffering from higher rents and energy prices.

Some economists suggest they would have given the budget a higher rating had it done more to fight inflation. To quote one of the toughest dissenters, David Byrne of the University of Melbourne:

Any claim made by the government that fiscal spending will be non-inflationary is nonsensical and ignores a century worth of economic research.

This is the basic Economics 1 model of inflation: more money into a fixed capacity for production means higher prices. Q.E.D.

Mathematically that equation is straightforward, but it ignores the complexities of the economic system. Even if the government’s spending to reduce the price of rent, pharmaceuticals, and electricity causes measures of inflation to rise (and there is no certainty that it will do so), consumers, particularly those in most need, will enjoy the benefits of lower prices. We should not confuse the metric – in this case the CPI – with the actual effect on people’s standard of living.

John Quiggin of the University of Queensland, who has long experience in consumer economics, believes the budget has been developed with too great a concern with inflation indicators, rather than its effect on people. He states:

We have achieved full employment for the first time in 50 years, and the government is throwing it away in pursuit of an arbitrary inflation target.

Although the claimed theory is that inflation reduces real wages, the actual strategy involves further downward pressure on money wages, leaving workers worse off than if we allowed wages to rise to offset past inflation.

The public’s response – assessed as mostly harmless

The government should be reasonably pleased with the response to the budget as revealed in the post-budgetEssential poll.

It compares people’s expectations from this budget with expectations from previous budgets – three Coalition, one Labor. This budget scores well in people’s expectation that it will do well for people on low incomes. It also finds that it less likely to “place unnecessary burdens on future generations”.

On the issue of a cash surplus, it asks respondents to choose between two statements:

The government has done the right thing in delivering a budget surplus that will ease pressure on inflation.

and

The government should have used the money to provide direct support for people under cost of living pressure.

Unsurprisingly a majority go for spending. But surprisingly Coalition supporters were much more likely to go for spending than Labor voters.

Willliam Bowe, on his Poll Bludger site, reports on a Resolve Strategic poll, which shows a positive response to the budget, in terms of both personal and national outcomes. He has another post on the post-budget Newspoll, which finds that people believe the economy will benefit from the budget, but they will be worse off personally. It’s hard to know what people see as “the economy”. Is it to do with people’s material living standards, as anyone familiar with economics would understand, or do people see “the economy” as some god to be appeased with sacrifices necessitating austerity? The latter is manifest in the common belief that there must be some trade-off between “the economy” and “society”.

Notably, the Newspoll found that 35 percent of respondents believed the Coalition would have done a better job, while 49 percent believed it wouldn’t have.

In polls on voting intention, covered by William Bowe, there is no movement that would be outside the range of sampling error. There is no evidence that Labor’s strong lead over the Coalition has moved up or down, but there does seem to be a little rise in voters’ preference for Albanese over Dutton.

The polling companies did their surveys before Dutton did his budget in reply, but on Late Night Live Amy Remeikis, The Guardian’s political reporter, suggests that those who are tuned in to social media paid far more attention to the Greens’ response than to Dutton’s, largely because Dutton used a traditional political spin while the Greens were more direct and used straightforward language: Amy Remeikis’s Canberra. (15 minutes) Perhaps in the government’s next budget the Greens should be called on to provide the budget-in-reply. More people may tune in.