Other economics

Is the Reserve Bank trying to crush the economy or is it just misinterpreting the stats?

The Reserve Bank’s statement on its decision to raise the cash rate target by another 25 basis points is strange, to put it charitably. To quote:

Inflation in Australia has passed its peak, but at 7 per cent is still too high and it will be some time yet before it is back in the target range.

It goes on to state:

The combination of higher interest rates, cost-of-living pressures and the earlier decline in housing prices is leading to a substantial slowing in household spending. While some households have substantial savings buffers, others are experiencing a painful squeeze on their finances.

Notably there is no mention of the yet-to-be-realized shock to be experienced by people with maturing fixed-rate mortgages, which will be refinanced at higher interest rates.

Nor is there any mention of the Commonwealth budget, due to be presented just a week later. A criticism of the Reserve Bank in the recent review is that monetary and fiscal policy are too disconnected. Could not the RBA have waited another month to see where the government is taking fiscal policy, and how the financial community is responding to the budget?

To re-use an analogy, managing monetary policy has much in common with steering a powerful but slow-to-respond riverboat. By the time the boat starts to respond to the tiller it is usually time to ease off. Otherwise the boat will start heading for the opposite riverbank, catching the driver by surprise. The riverboat is a physical example of a big system with a great deal of momentum and with powerful but slow-acting controls.

Justifying its decision, the Bank states that inflation is 7.0 percent. It has no basis for making such a strong declarative statement in the present tense.

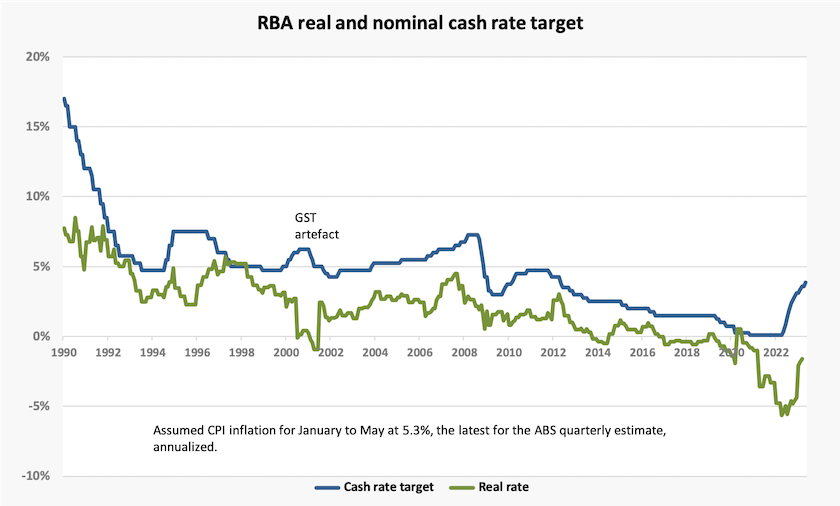

The ABS has found that CPI inflation over the year to March 30 was 7.0 percent. In the same statistical release that the ABS reports on inflation over the last 12 months, it also provides an estimate of quarterly seasonally-adjusted CPI inflation of 1.3 percent – 5.3 percent annually.

The graph below, of nominal and real rates, shows how quickly the RBA is moving. At this pace it’s surely headed for the opposite bank.

Another strange assertion attributed to RBA Governor Philip Lowe in a dinner speech after the announcementis that rebounding property prices have contributed to the Bank’s decision. But higher interest rates, in making housing more expensive, constrain supply and actually raise house prices. Does Lowe not acknowledge the influence of this positive feedback loop?

On a matter also related to housing, Glen Holman, former head of credit risk at the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority, states that he regrets APRA’s 2019 decision to drop the interest-rate floor, a decision made in response to lobbying from the banks and welcomed by then Treasurer Josh Frydenberg, who were keen to see more lending for housing.

That floor, 7.25 percent before it was scrapped, was not an absolute lower limit, but it was used to stress-test mortgagees. They may have been taking loans at much lower rates, but they still had to demonstrate they had the means to re-pay them if rates rose to 7.25 percent. It was the financier’s equivalent of the engineer’s safety margin.

Such a test was particularly important in the period of low interest rates, when housing loans could be taken out at rates as low as 2.5 percent. A 25 basis-point rise on a loan at 2.5 percent is a 10 percent rise. That’s much more of a financial shock than a similar rise on a loan at 5.0 or 7.5 percent interest, the rates of earlier times. In its 11 interest rate rises since last May the RBA has never acknowledged the reality that its interest rate rises are proportionately more severe than rises of previous times.

Another justification for the RBA’s decision, implicit in its press release, is that wage growth is now playing a major role in inflation growth. Evidence for this is that inflation in the cost of services is high.

It is true that services inflation has been strong in recent CPI figures, but goods inflation is still higher. The Australia Institute provides a partial rebuttal of the RBA’s assertion about the contribution of wages to inflation in a short piece of research: Minimum wages and inflation, showing that, historically, there is no correlation between minimum wage rises and inflation.

The Hobart stadium: where’s the economic justification?

Stylish buildings, but why should our taxes pay for them? (Adelaide stadium)

There is great excitement about the government committing $240 million for a sporting stadium on Hobart’s Macquarie Point.

Not all that excitement is positive, however.

How can the government justify spending $240 million when Tasmania has severe shortages in public housing and when Hobart has terrible traffic congestion calling for road and public transport funding. And why should Macquarie Point be given over to a facility that will be used only one day a week, if that?

Cody Atkinson and Sean Lawson, two ABC sports journalists who have a way with numbers, have a post How the Hobart stadium spend is a game-changer in Australian sport and the AFL.

It’s a data-rich description of an arms race in government spending on facilities for elite sports, particularly stadiums that inevitably run over budget. Both the Commonwealth and the states are involved.

It reveals that the Hobart stadium, on present estimates, has a net present value of benefits of minus $306 million. That is, while the discounted value of costs is $618 million, the discounted value of benefits is $312 million. Another way of expressing this is that its benefit-cost ratio is 0.5:1.If it were a road project it wouldn’t make past Infrastructure Australia’s in-tray.

There is an economic case for funding sport and recreation, based on the public health benefits of participation in sport. There is also a strong case in the economics of market failure for spending on local playing fields, because there is no practical way for the market to provide such facilities. In the terminology of economics, these facilities are “non-excludable” because their use cannot be rationed by user charges. That’s why, as Atkinson’s and Lawson’s figures show, most sport and recreation spending is by local government.

But there is no more a market failure case for public funding of a stadium for elite sports than there would be for public funding of a brewery or a cinema. We pay for beer by the glass or can, and a cinema charges for a seat to watch the movies. Similarly people pay for a seat at the stadium to watch people playing with a ball. Almost by definition a stadium is excludable. That is, people can be charged admission. The market can work.

Also, there is no public health benefit in people sitting on their backsides watching others play. If spectator sport displaces sport participation, its public health effects would be negative.

If people enjoy watching football so much – and there is clear evidence that they do – then they can pay for it themselves, just as they pay for beer and movie tickets. Without public funding the facilities they fund may be less elaborate, and players may not be paid astronomical wages, but people would still be enjoying their football. In fact those astronomical wages may have their own negative effects in enticing young people away from their studies – young people who don’t understand how only a few people prosper, and only for such a short time, in elite spectator sports.

What explains this idiocy? It’s possibly a political bribe: three of Tasmania’s five House of Representative seats are marginal (two held by the Liberals, one held by Labor), but these are in the north of the state, not in Hobart. The two Hobart seats are anything but marginal: Labor holds Franklin with a 27 percent margin and Andrew Wilkie holds Clark with a 42 percent margin. If the motivation were pork-barrelling one may have expected the government to have gone for a project in Launceston.

Nevertheless, in view of the project’s lack of economic justification, it should be examined by the yet-to-be-established Commonwealth anti-corruption commission. Corruption isn’t just about bribes and favours for mates: it is also about poor processes that fail to protect the public interest.

Or, as is more likely, it may be explained by a lack of basic economic expertise in the Canberra bureaucracy. The “public choice” model of government, that is consistent with neoliberalism, and to which many public servants have been exposed in their university studies, posits that there is nothing of value in public expenditure: it’s all waste. In fact such a belief is embedded in the Liberal Party’s statement of beliefs. A stadium, Medicare, a freeway – it’s all frivolous expenditure of money that could be far better spent in the private sector. By the public choice model the only justification for spending public money is to bring enough voters along to win re-election.

While Labor and Coalition politicians may have trouble grappling with the basic economics of public finance, Senator Tammy Tyrell of the Jacqui Lambie Network understands that the people of Tasmania would prefer public funds to be directed to other needs, particularly housing, and she points out that Tasmania already has two “beautiful stadiums”. Do Tasmanians want a new stadium? on ABC Breakfast (7 minutes).

As Felicity Rea writes in Croakey, the stadium, if built, would be “a monument to the moneyed few who benefit from the ‘industry’ of corporatised sport”.

Inequality in Australia – in all its dimensions

There are many studies on inequality that take a snapshot of income distribution. There is the HILDA surveycollecting longitudinal data about aspects of well-being, and there is some limited ABS data on the distribution of housing and financial wealth.

The Institute of Actuaries has added to our knowledge with a survey – Not a level playing field -- that goes into many dimensions of income and wealth inequality, and the causes of these inequalities.

As with other surveys it confirms that inequality has widened since the 1980s, and that wealth inequality has widened much more than income inequality. It goes into detail about the distribution and causes of poverty. For example it explores the separate contributions to poverty of age, education, employment, gender, disability, geography and country of birth.

It lists five long-term trends contributing to wider inequality: an unwinding of redistributive policies, globalization, low wage growth (while profits rise), the fall of unions, and structural factors that restrict investment in human capital. (Not all these factors are independent: wealth inequality, in itself, impedes people’s opportunities to invest in human capital.)

The authors believe that inequality should be a prominent consideration in public policy. They suggest a raft of polices relating to taxation, social security and investment in public services.

There is a short summary of the work on the ABC’s The Money program, where Richard Aedy interviews Elayne Grace of Actuaries Australia about their work. (From 10 minutes into the program to 20 minutes).

Health policy: it’s not just money

On April 28 National Cabinet announced a major set of initiatives to reform health care. There is a fair bit of publicity around the $2.2 billion announced in the National Cabinet statement, but we don’t know whether that’s over one or four years, and what proportion is to come from the states and what is to come from the Commonwealth.

Anyway, to put that figure in perspective, in 2019-20 total health expenditure was $203 billion, of which $143 billion was from governments.

But these initiatives, outlined in the Commonwealth Minister’s press release, aren’t primarily about spending more money on existing arrangements. Rather, they are about getting more from existing resources. In particular they are concerned with making more use of primary care resources including GPs, nurses, pharmacists, and ensuring that conditions can be treated early and out of hospital, thus relieving the load on hospitals.

Norman Swan has a short description of the initiatives in an interview on the ABC (6 minutes), and the Commonwealth Health Department has a table describing 13 specific initiatives, such as improving after-hours primary care and making more use of pharmacies in immunisation.

This table doesn’t list cost-saving reforms already in train, such as doubling prescription volumes for certain medications. Henry Cutler of Macquarie University, writing in The Conversation explains why pharmacists are angry at script changes – and why the government is making them anyway. It’s a rare instance of the government standing up against the quaintly-named but politically powerful Pharmacy Guild.

Most of these initiatives are about integrating health services within the primary care system. Writing in Independent Australia David Shearman, Emeritus Professor of Medicine at Adelaide University and the co-founder of Doctors for the Environment Australia, reminds us that health care programs, while important, are not the only determinants of our physical well-being: poverty, poor education and environmental degradation all play their part in contributing to poor health: Deteriorating health, housing and education upshot of inequality.

China-America relations from an economic perspective

Most media comment on China-US relations is in terms of military rivalry. Tom Friedman, in conversation with Geraldine Doogue on Saturday Extra, looks at the way the relationship has developed from an economist’s perspective – America, China and trust (18 minutes).

Friedman can always be counted on to provide new insights into economics. He points out that China and the US, in terms of their economic culture, are similarly driven by a “Protestant” work ethic and a natural tendency to capitalism. Over the last 40 years the two countries became quite strongly economically integrated, but as China moved from specialization in simple manufactures such as clothing, and into high technology, such as Huawei’s 5G, that economic relationship has become more distant.

He puts that development down to trust, or the lack of it, between the two countries. When a country is selling T-shirts and sneakers, using generic technology, there are no issues in sharing technological information. But for sophisticated technologies, trust is crucial, because technological knowledge has to be shared. The success of Taiwan’s TSMC, the firm that dominates the world market in microchips, lies in the trusting relationships with global companies who use those chips, and who of technological necessity share their designs with TSMC. They would not be willing to risk such sharing with Chinese firms.

Friedman concludes with his observation on a coming world divide. It is not between China and the US as many see it. Rather it is between countries that are ordered and those that are disordered. In the first category are China, the US, Australia, and many others. In the second are Afghanistan, Pakistan and many others. Russia is shifting from the first to the second category.