Australia’s energy transition

China’s push to net zero – is Australia missing the boat?

With 29 percent of the world’s carbon dioxide emissions, per-capita emissions that are much higher than those in developing countries, and a 2060 commitment to net zero rather than a 2050 commitment, the notion of China as a greening economy does not come easily to mind.

But in an authoritarian state policies can move quickly.

Anthony Coles of the Australia Business Council brings us up to date on China’s energy policies in an interview on the ABC’s Saturday Extra: Working with China on net zero (14 minutes). He reports on a visit to China involving government officials and executives from Australian companies, including Rio Tinto, Fortescue Metals and Telstra.

We already know that China will reach peak coal use in 2030: that has significant implications for our mining sector. But we are generally less aware of China’s ambitious plan to become a green economy, and to collaborate with other Asian countries in this process. Those collaborations range from establishing sources for critical minerals, through to investing offshore in battery and electric car manufacture.

Coles sees big opportunities for Australia in our trade with China, not only in export of minerals needed in a greening economy, and possibly hydrogen, but also in joint ventures involving two-way technology transfer.

Electric vehicles – still waiting for a policy

There was a great deal of media speculation about the Commonwealth’s policy on electric vehicles, but when the National Electric Vehicle Strategy came out it turned out to be an insipid piece of work. It’s full of fine words, but apart from a commitment to build 117 charging stations in partnership with the NRMA (a New South Wales motoring association), it is remarkably short on anything concrete. For example, on affordability, it states that it will collaborate with the states “encouraging initiatives to reduce costs and increase affordability. This may include assessing the impacts of incentives as EV uptake increases.”

The ministers’ press release mentions the Electric Car Discount, saving up to “$11 000 a year on a $50 000 electric vehicle”, but don’t get your hopes up, because a little digging reveals that it applies only to vehicles bought on a business account. Lesser mortals, lacking an ABN, can pick up second-hand cars once their corporate owners have thrashed them.

The document, pretentiously called a “strategy” (whatever that means), lacks the two essential items that would allow it to qualify as a policy – fuel efficiency standards which would shift the market away from internal combustion engines (ICE) towards electric, and ways EVs will pay for roads.

On the first, the report notes that “Australia has been next to Russia as one of the only advanced economies without a Fuel Efficiency Standard”, and that “on average, new cars in Australia use 40% more fuel than the European Union, 20% more than the United States, and 15% more than New Zealand”. This is hardly surprising: thanks to unjustified tax concessions for anyone with an ABN, our three biggest selling vehicles are the Toyota Hi-Lux, the Ford Ranger, and the Isuzu D-Max. Having drawn attention to the problem, however, rather than going ahead with EU or similar standards, the government has issued a consultation paper.

On the way EVs will pay for roads, the “strategy” paper simply kicks the issue down the track, with a few paragraphs about fuel excise, asserting that:

The 2022-23 October Budget forecasts fuel excise to continue to grow year-on-year over the forward estimates, with CPI indexation, population and economic growth contributing factors. The impact of EV uptake on fuel excise has been factored into these estimates, but given current low uptake rates, the impact is minimal.

The Commonwealth collects around $19 billion a year in fuel excise – $6 billion from gasoline, $13 billion from dieseline. Commonwealth excise contributes roughly one third of government road expenditure.[1] If there is a significant uptake of electric vehicles that revenue stream, particularly the $6 billion from gasoline, will reduce, and states, seeking money for road construction and maintenance, will come to rely on inefficient, inequitable and distortionary taxes and charges on EVs. These include tolls, higher registration fees, and Victoria’s clunky bureaucratic system requiring EV owners to photograph their odometers regularly.

Maybe the present situation is too fluid to allow the government to make any definitive statement on how EVs will pay for road use, but the ministers could at least have spelled out some principles that will guide their policies. Do they favour fixed fees or fees based on km travelled? Should heavier vehicles pay more (some EVs are significantly heavier than their ICE counterparts)?

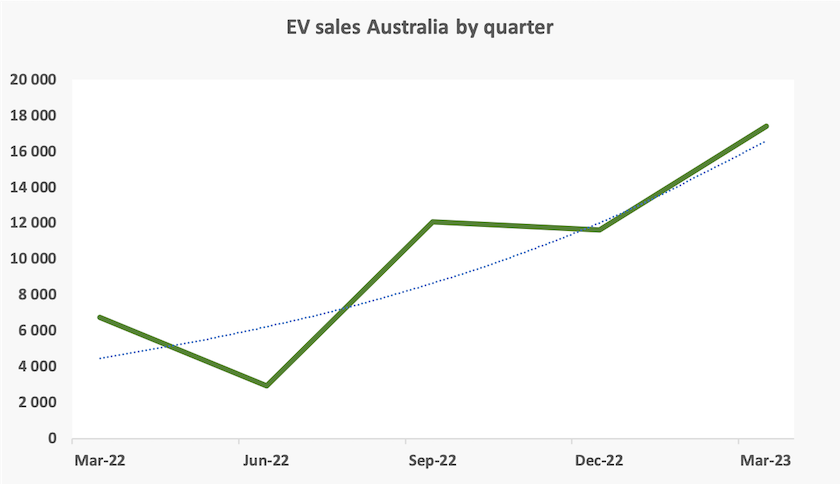

The ministers’ confidence that the problem of road user charging can be deferred seems to be misplaced. EV sales are indeed still small, but they are growing quickly. In the March quarter this year they accounted for 6.8 percent of new light vehicle sales (i.e. excluding large trucks) in Australia, up from 2.7 percent in the same period last year. That growth is probably exponential rather than linear. The exponential line of best fit (the dotted line in the graph below), if projected out, suggests that within 5 years EVs will account for more than half our light-vehicle sales of around a million vehicles a year. OK – logistic growth tends to slow down, but policymakers are often caught out when they assume growth will be linear.

1. Fuel excise is not hypothecated to road expenditure, but state governments and motoring associations keep a close eye on taxes associated with motoring and on road expenditure, and squeal rather loudly when taxes and spending get far out of line. ↩