Other economicss

How the gains from economic growth are distributed

It is hardly news that over the last 50 to 70 years Australia has become a more unequal society. Our distribution of income has become more unequal, and this has led in turn to a widening and more enduring inequality in the distribution of wealth.

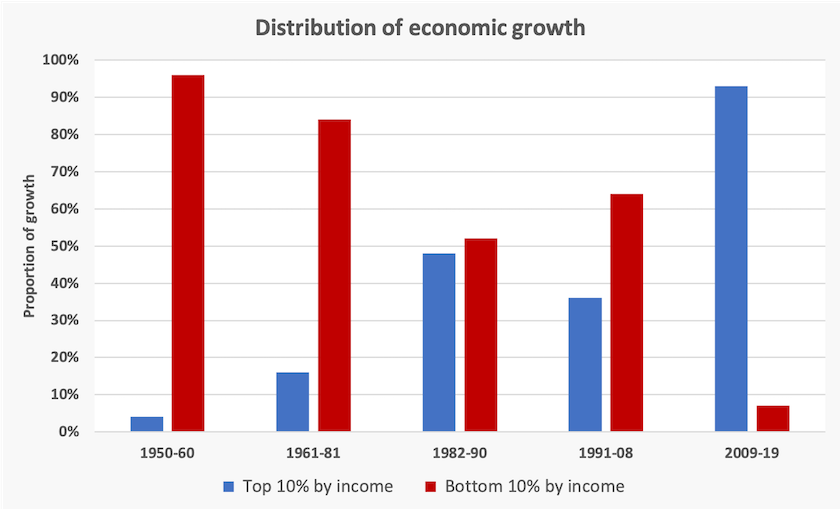

A paper by David Richardson and Matt Grudnoff of the Australia Institute – Inequality on steroids: the distribution of economic growth in Australia – shows how over that long period in each bout of economic growth the benefits have increasingly been distributed to the already well-off. In the 1950s, for every dollar of growth, 96 cents went to the bottom 90 percent, while only 4 cents went to the top 10 percent. In the latest period of growth that situation has been almost entirely reversed: only 7 cents have gone to the bottom 90 percent, while 93 cents have gone to the top 10 percent.

The graph below, drawn from the paper’s data, shows that in the 1950s the distribution of growth was mildly progressive, with more than 90 percent of the benefit enjoyed by the bottom 90 percent. But ever since then the distribution has been regressive.,

In effect Richardson and Grudnoff are demonstrating the dynamics of income distribution. If one simply considers the way income is already distributed, the trend towards inequality looks like a slow process from around 1980 to the present day. But what Richardson and Grudnoff present, drawing on the World Inequality Database, is an analysis of how the growth in income has been distributed.

A critic of their work may point out that their findings relate to income before tax and social security transfers, which compensate for inequalities in private income.

That is so, but the greater the inequality in private income the greater is the task falling on taxation and social security. We could make our income tax system more progressive – and not do dumb things like the Stage 3 tax cuts – but there are strong political forces against progressive income tax. Social security transfers have two fundamental problems: their recipients develop a sense of dependency, and as these transfers grow they crowd out other areas of public expenditure that contribute to long-term prosperity.

It’s better to get the distribution right in the first place.

The IMF’s economic outlook – feeble and uneven growth

On Wednesday the IMF released its 6-monthly World Economic Outlook, bearing the sub-heading “A rocky recovery”. (The sub-heading in the October 2022 Outlook was “Countering the cost-of living crisis”.)

It forecasts world economic growth to fall from 3.4 percent in 2022 to 2.8 percent in 2023 and to recover a little to 3.0 percent in 2024. That’s unsurprising as economies, after coming out of the Covid shock, revert to more modest growth rates.

Apart from its forecasts for inflation (expected to be higher) most of its forecasts are little changed from its October 2022 Outlook or its January 2023 update, which was generally gloomy for European countries. It also forecasts a continuing downturn in world trade.

It draws attention to risks in the finance sector. While it cautiously believes that the financial sector will stabilize after recent minor shocks and a rapid rise in interest rates, it warns governments to be ready to react should anything go wrong in the finance sector.

Its medium-term outlook is for slow economic growth. It notes the presence of “ominous” forces:

… the scarring impact of the pandemic; a slower pace of structural reforms, as well as the rising threat of geoeconomic fragmentation leading to more trade tensions; less direct investment; and a slower pace of innovation and technology adoption across fragmented “blocs”. A fragmented world is unlikely to achieve progress for all or to allow us to tackle global challenges such as climate change or pandemic preparedness. (Page xv)

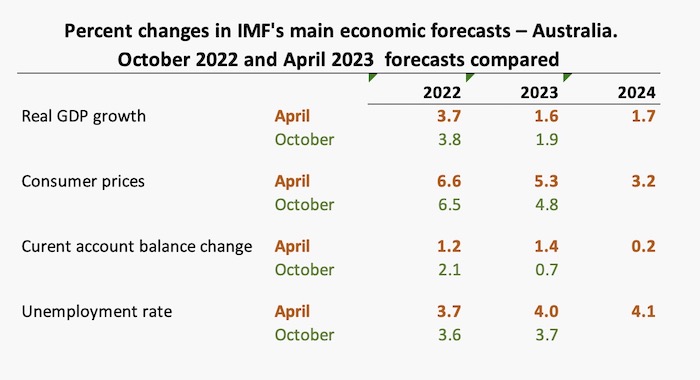

Its forecasts for Australia, compared with its October 2022 forecasts, are shown in the table below. Notably its forecast for economic growth is down, and its forecast for inflation is up. If GDP growth is only 1.6 to 1.7 percent that’s only in line with population growth, implying at best stagnant real average incomes.

These forecasts for Australia are generally more positive than its forecasts for Europe and the US. (In the UK and Germany growth is forecast to be negative this year.)

One of its warnings, relevant to Australia, concerns housing risk. To quote:

As central banks raised borrowing costs to fight inflation in 2022, real house price growth turned negative in both advanced and emerging market economies. If mortgage rates continue to rise, demand for borrowing is likely to weaken, further depressing house prices. Economies with elevated house prices and high levels of household debt issued at floating rates are particularly vulnerable to any ensuing financial sector stress. (Page 23)

They assess the level of housing risk for 27 countries, and Australia comes out as having the second-highest level of housing risk. This contrasts with the hype from the real-estate industry about an imminent “recovery” in house prices.

Budget advice: raise taxes, cut spending, don’t cut programs

By now the 2023-24 Commonwealth budget would be fairly well in place.

Looking into the longer term the Grattan Institute has produced a report Back in black? A menu of measures to repair the budget, addressing ways to arrest the growing structural deficit, growing each year at $50 billion or 2 percent of GDP, which will go on unless the government raises revenue, cuts spending, or does both.

Talk about “budget repair” usually leads to calls for austerity, involving deep cuts to government programs. (It’s an unfortunate term because of its partisan connotations), but the authors do not resort to such simplistic and economically destructive approaches.

They start by emphasizing the need for more public revenue, which has not kept pace with spending, and they point out that our taxes are significantly lower than in other prosperous “developed” countries, even when we classify compulsory superannuation as a “tax”. (In most countries retirement incomes are funded through taxes.) They stress that our tax system is “leaky” because of the growing costs of concessions and tax minimization.

Nevertheless they start with options to reduce spending, but their recommendations are mainly about cutting waste, improving the efficiency of program delivery, and cleaning up government boondoggles. They are about cutting spending, not cutting services.

They see big possibilities for saving in government procurement in defence and transport infrastructure, where there have been blowouts in spending on major projects, often committed before there has been adequate evaluation. For example the blowout in transport infrastructure costs has been in megaprojects costing more than $5 billion, while expenditure on more modest projects has contracted. (In this roundup there is an entry on inland rail, a project that has undoubtedly robbed funds from other necessary road and rail projects).

They see opportunities for savings in health care, through more disciplined spending on hospitals and pharmaceuticals, but in ways that don’t involve a decline in the quality of service. There are many corporate snouts drinking copiously from the trough of health spending, particularly in pathology and pharmaceuticals.

On revenue they call for a “re-design” of the Stage 3 tax cuts, and a reduction of income tax breaks relating to superannuation contributions, trusts and capital gains. They also recommend an increase in the GST to 15 percent. They see ways to gather more taxes from the corporate sector, particularly from the export gas industry, which is very lightly taxed.

Some may see their 15 percent GST proposal as the most controversial, but they point out that if it’s part of a package it need not be regressive. In terms of material and political consequences their most difficult recommendation is undoing Morrison’s special GST deal for Western Australia, costing $5 billion a year “to support superior government services in the only state that is running a strong surplus”.

They correctly identify the extent of waste in public expenditure. Some results from straight out cronyism, some from privatization and contracting out, and some from simple managerial incompetence. Cleaning up this mess will take not only the political will for government to confront privileged lobbies, but also for more competent management. Over the last 25 years, dating generally to the Howard government’s politicization of the public service, senior ranks of departments have been filled more by people whose qualities are loyalty and responsiveness to ministers, rather than managerial competence, particularly in finance and economics.

Reflections of a business journalist

On Saturday Extra last weekend, Geraldine Doogue interviewed Tony Boyd, former “Chanticleer” columnist for the Financial Review on prospects for the global and Australian economy.

Globally he is concerned about a withdrawal from globalization in many parts of the world, as countries retreat to protectionist policies. Although Covid-19, with its supply-chain disruptions, promoted concerns for self-sufficiency, he believes the world had already passed peak globalization before Covid-19 hit. He is also concerned by the prospect of a US recession as higher interest rates wreak their economic damage.

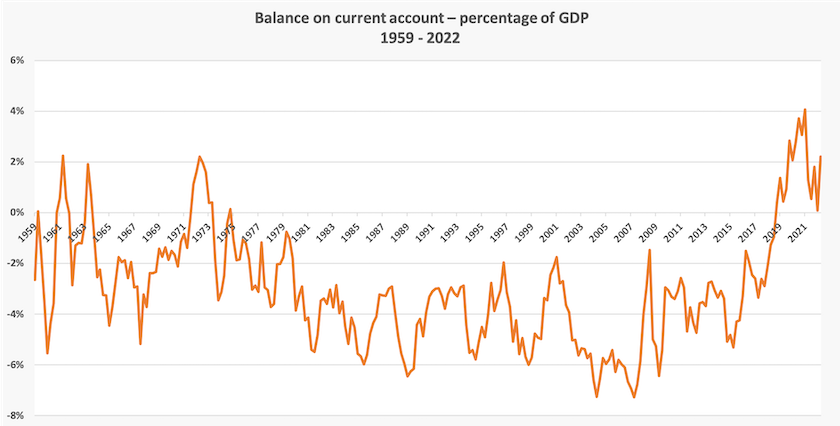

Domestically, he notes that compulsory superannuation has driven a huge financial transformation in Australia. For much of our history we have been a capital-importing country, but from around 2005 we started closing our current account deficit and for the last few years have been running a current account surplus.

That means we have funds to invest locally and globally, particularly for energy transformation, but many of our firms are still gripped by risk-aversion in the face of global uncertainty. We cannot defer that transformation however, as the world’s transition away from fossil fuels reduces demand for our coal. Unless we invest in that transformation that current account surplus may be short-lived.

A current account surplus is not, in itself, necessarily a good thing. But it does mean that governments have more capacity to borrow for investment than the governments of countries with a current account deficit, which is one of the main concerns recorded in the latest IMF Outlook.

Inland rail – echoes of misadventures past

In August 1860, with a great deal of fanfare, Burke, Wills and 17 other expeditioners set out from Melbourne northwards, on what to then was the most extravagant such venture of Australia’s history. They weren’t entirely sure where they were going, used the wrong equipment, made mistakes from the outset, and as they went further north they found the going harder particularly when they ran into boggy ground, and ran further behind in their schedule. Only one member, John King survived to return to Melbourne.

In April 2023 the government released the findings of the Independent Review of Inland Rail, a review commissioned by the government in view of the project’s serious delays and cost overruns. The report, signed off by the Review’s Chair, Dr Kerry Schott, is highly condemnatory of the project’s management. To quote:

The problem is that the Board and its Sub-Committee do not have adequate skills to oversee this project. Despite an informed request by the Chairman of ARTC [Australian Rail Transport Commission] to the then-Minister responsible [Barnaby Joyce], replacement appointments to the Board did not provide the skills required. ARTC is a large business and its management does need a capable Board with a knowledge of rail operations, project management, the freight industry and regional nous as well as legal and accounting skills.

The project’s budget has blown out from $16 billion in 2020 to $31 billion now, and the completion date, originally 2016, has been pushed out to 2031. Some of the worst cost blowouts are on a section near Brisbane, which is being handled by a private-public-partnership.

Extraordinarily the project was commenced without a firm plan of where the line will terminate. To quote the report “Somewhat surprisingly the project has commenced delivery without knowing where it will start or finish”. One does not bring a freight line into a city centre: rather such a line should terminate at a freight distribution centre, usually on a ring road. Those vital elements are yet to be planned.

The starting and ending points can be complicated – best to ignore them

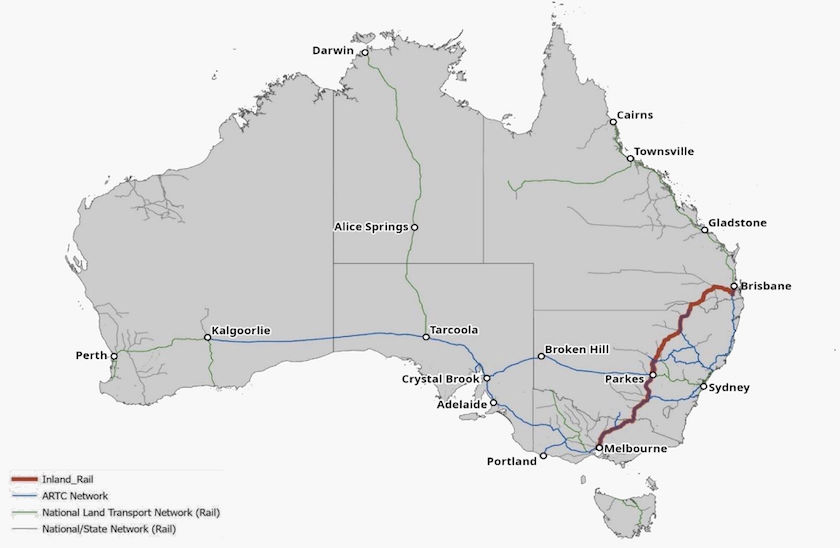

Minister Catherine King describes it as “1700 km of Liberal National Party incompetence”. That may be a little too kind on the recently-departed government, because only the 700 km from Melbourne to Parkes is well-advanced, on track for completion by 2027. Notably, almost all of that is on existing track that is being upgraded – the comparatively easy part. It’s the need for new track, north of Parkes, in New South Wales and Queensland, that is causing difficulty.

The project never got enthusiastic support from Infrastructure Australia. Its 2016 evaluation of the project yielded a benefit:cost ratio of only 1.1 at a 7 percent discount rate and 2.8 at a 4 percent discount rate. With an almost doubling of capital costs those ratios would be close to halved. It would still stand up at a real discount rate of 4 percent, which is probably near the Commonwealth’s cost of capital, but not at 7 percent.

Infrastructure Australia evaluates projects at a 7 percent rate because that is roughly the rate that absorbs the Commonwealth’s capital budget. Looking at it another way, even though inland rail may be viable at the Commonwealth’s 4 percent cost of capital, there are many better projects that aren’t being funded because successive Commonwealth governments have been imposing tight limits on capital spending.

Notably in that 2016 evaluation Infrastructure Australia wrote in its risk analysis that “Australian coal exports are an important driver of demand for Inland Rail” and warns that the future outlook for coal is uncertain. Presumably Barnaby Joyce and his advisers overlooked that part of the report.

By now there is so much sunk cost in the project that even with the cost blowouts it is probably economic for the government to complete the project.

The map below, copied from the Schott Report, shows that with Parkes in the network it will be useful in displacing truck traffic between Sydney and Melbourne. That will have safety and emission benefits. It’s a pity, however, that the locomotives will be diesel.

In terms of partisan politics, this has been yet another example of the corruption that flourished under the Morrison government.

But there are broader public policy issues that the current government could be tempted to overlook. They relate to the way capital projects are planned and budgeted.

The first, illustrated in this case, is the use of high discount rates for project evaluation. Those discount rates (a real rate of 7 percent is typical) are much higher than the government’s cost of capital, generally reflected in the long-term bond rate.

In setting high discount rates for public projects government sacrifices the public interest to private interests, for it deliberately withholds its demand on the capital market in order to leave a larger share for the private sector. Far from “crowding out” the private sector, successive governments, under the guise of avoiding or reducing public debt, have been allowing the private sector privileged access to capital markets. To paraphrase JK Galbraith, it puts us on the path to private affluence and public squalor.

The other issue is the way public projects can get spun out over a long period, fed with a trickle of funding. That pushes out the time when a project is completed and starts to deliver its benefits. That waste is a cost of pubic investment being treated as a by-product of fiscal policy, as something to be funded only when the private sector is in a cyclical downturn, rather than as wealth-creating in its own right.

How public policy encourages Australians to buy high-emission passenger vehicles

Have a glance at the two vehicles below, parked at a suburban tennis club. On the right-hand side of the picture is a Toyota HiLux, which last year was Australia’s top-selling motor vehicle. The other is a slightly older Holden Colorado, a twin-cab utility. Both are strong, heavy, high fuel-consumption vehicles designed for commercial use.

Their strange aspect is their spotless condition. Vehicles used in businesses get knocked around on farms and building sites; they are fitted with accessories such as winches and hoists; their doors are painted with the name of their owner’s business.

The Australia Institute has a short paper – In reverse: The wrong way to fuel savings and falling transport emissions – explaining how a combination of poorly-designed Commonwealth and state taxes, lax fuel efficiency and emission standards, and a lack of effort to deal with transport sector emissions, has brought about a situation where the fuel consumption of our passenger vehicles is close to the highest among all OECD countries.

The authors explain that tax concessions for small business, including rapid depreciation provisions, have encouraged people to buy these dangerous vehicles rather than small, fuel-efficient passenger cars, even though they are mainly used for private purposes. They explain that “the full cost of top-selling dual-cab utes can be written off instantly as an annual expense”. Almost anyone with an Australian Business Number can take advantage of this rort. That explains the phenomenon of “hairdressers with HiLuxes”

The paper concludes with seven recommendations, to do with fuel efficiency and emission standards, and the need to hasten a transition to electric vehicles. It could add an eighth recommendation that the owners of pristine quality commercial vehicles should be subject to an immediate tax audit.

Early childhood: neglected public investment

“Give me a child till he is seven years old,” said Ignatius Loyola, the founder of the Jesuits, “and I will show you the man.”

Even if he forgot to mention women (16th century Spain was not particularly woke) he was on the right track: early childhood education counts. The education and socialization of young children is crucially important in terms of how individuals and societies turn out.

Yet as Martyn Goddard points out in his Policy Post, in Australia we are laggards in comparison with other countries: Early childhood: the neglected frontier that impacts almost everything. In comparison with the world’s most prosperous “developed” countries, Australia sits at the bottom in terms of participation of three- and four-year-olds in early childhood education.

We are not spending enough to bring early childhood enrolment up to the levels in other countries, and that’s largely because we rely on parents, rather than taxpayers as a whole, to fund early childhood education. Only a third of Australians report that they can “comfortably afford” to pay for early childhood education and childcare. That’s why public funding is important, and it’s where we fall down.

Goddard acknowledges that the Commonwealth’s commitment to spend an extra $1.7 billion a year on early childhood education will go some way, but it isn’t enough.

He develops a strong economic case for public funding for early childhood education. That case goes beyond the economic benefits of freeing parents to join the workforce. There are returns to society and to public budgets, but these benefits take many years to realize. In terms of normal cost-benefit analysis, the benefits have to be very high to yield a high net present value.

When all benefits are brought to account, however – and some of them are hard to measure – they do reveal a significant economic justification for public investment.

Perhaps the greater problem is that those benefits don’t realize for several electoral cycles: it would take a Menzonian term in office for a government to be around long enough to boast about outcomes. In some unorthodox but rigorous accounting, Goddard demonstrates that it would make good economic sense for governments to borrow for early childhood education, which should properly be viewed as investment rather than recurrent expenditure.

Goddard’s analysis and policy recommendations align closely with the work of the Centre for Policy Development in its 2021 project: Starting better: a guarantee for young children and families.