The New South Wales election

Last Saturday’s election in New South Wales has national implications. It is yet another sign that nationally the Coalition is on the way out. And because it re-defines Labor’s “working class” base, it has significant implications for public finance: we cannot keep on ducking the need to pay higher taxes.

Is the Coalition on the way out?

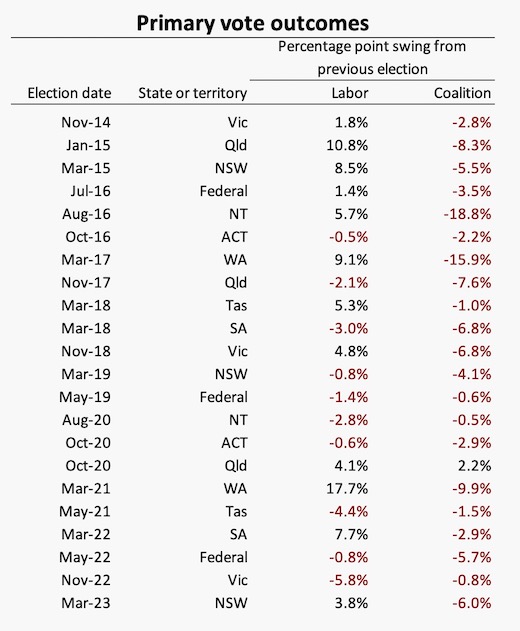

Over the last 9 years there have been 22 elections, state and federal, in Australia. In 21 out of these 22 elections the Coalition’s primary vote has fallen.[1] This run of dismal outcomes is shown in the table below which has been appearing, in an ever-lengthening form, in these roundups.

The Coalition’s spokespeople have become expert at rationalizing its election losses: they have had plenty of practice. In last Saturday’s election commentary those rationalizations were “it’s time” after three terms, and subtle references to the lingering stench of the corruption and mismanagement of the Morrison government. Anything but policy.

Does this mean Labor is now in absolute power, at least on the mainland? Frank Bongiorno, writing in The Conversation, reminds us that while Australia is now almost entirely held by Labor, that doesn’t necessarily make life easier for leaders. Although we may have 7 “Labor” governments they all have their own ideologies, and 6 of them represent state and territory interests involving fiscal conflicts with the Commonwealth. Bongiorno also reminds us that while there have been previous clean sweeps of Labor or Coalition governments in the past they have been short-lived.

Couldn’t win it back from an independent

Writing in The Guardian – Five things Australians can expect now Labor rules federally and across the mainland – Caroline Riches makes a similar point, and reminds us that while such dominance may remove a few roadblocks from a reformist Commonwealth government, it also removes political excuses for inaction.

What stands out this time is the continuing decline in the Coalition’s primary vote, which has been between 32 and 36 percent in most recent elections (35.6 percent in the New South Wales election). It would take a strong showing by far-right parties for their preferences to get the Coalition over the line: those who vote for fringe parties tend to be poor followers of “how to vote” cards.

Polls are showing that only among older voters does the Coalition enjoy strong support. As these voters die they are not being replaced by later cohorts: the old adage that as people age they become more likely to support right-wing parties no longer holds.

The present situation is unlikely to endure, but it would be a brave person who predicts the future of our politics. Maybe the Liberal Party will break with the National Party, discarding the stinking albatross hanging around its neck. But maybe the Liberal Party will dig in further to the right, hoping to gain some support from One Nation and others on the far right and lunatic fringe: if it does it stands to lose the few remaining adults in its ranks. Maybe the Liberal Party will re-constitute itself as Menzies did in 1944, and return to the centre of the political spectrum, but Dutton is showing no sign of such intentions. Maybe some of the adults will join with right-of-centre “teals” to form a new party, with responsible economic and security policies. Or maybe there will be a fragmentation and re-constitution of all parties.

So far there are few signs that the Liberal Party can reform itself. In Victoria parliamentary leader John Pesutto has failed to convince his colleagues to have Moira Deeming expelled from the party after she attended and apparently participated in a Nazi rally. In New South Wales former Treasurer Matt Kean, one of a handful of Liberals who understands economics and the need for structural transformation, is not standing for party leadership. A Menzonian reform does not seem to be on the cards.

1. The exception was the Queensland election in 2020, when the Coalition picked up support it had previously lost to One Nation. That 2.2 percent swing brought its primary vote only up to 36 percent. ↩

Has Labor finally rediscovered the working class?

On last Saturday night’s ABC election broadcast, while Coalition spokespeople were fabricating excuses and rationalizations for their losses, and Labor spokespeople were gloating about their political acumen, pollster Kos Samaras provided some insights into electorate trends.

Up to now the general observation has been that while the Liberals have lost ground in inner-city electorates to teals, Greens and Labor, they have made inroads in the outer suburbs, once considered as Labor’s working-class heartland. But in this election Labor has won back many of those outer-suburban seats, in many cases with significant swings.

Samaras identifies Labor’s promise to scrap the Coalition government’s public sector wage cap as a decisive factor in bringing these seats back to Labor. Commenting on the election, the ABC’s Ashleigh Raper writes about the cap as the anger that was staring Dominic Perrottet in the face. She quotes Samaras’s observation “Well, there is a slow realisation that this particular group, largely female, tertiary educated are overwhelmingly the biggest supporters of the red side of politics”.

Many pollsters have noted that women have been more favourably disposed to Labor than to the Coalition. Samaras offers at least a partial explanation: it’s because of their occupation as teachers, health-care workers and other professional workers either on the public payroll, or in occupations with similar pay and conditions (for example teachers in Catholic schools).

Some may see this development primarily as a gender issue, but a party’s response of merely endorsing more female candidates isn’t going to win votes from professional women. (The days when Catholics voted for Catholics and women voted for women are behind us.) These women are part of Labor’s working-class core. They rightly feel they have been taken for granted and disrespected, particularly in view of the way they bore much of the weight in dealing with Covid-19. While many in the private sector have been enjoying real wage rises, these people, whose work is essential for our health and prosperity in a way that the work of a real-estate agent, mortgage broker or advertising executive is not, have been under-valued.

The fiscal implication – higher taxes

In view of shortages in these public-sector dominated professions, it will make good economic sense for governments to raise their wages, and generally improve their working conditions. If New South Wales moves, other states will have to follow – unless they are to lose their teachers and nurses to New South Wales.

Because schools and hospitals account for about 50 percent of states’ recurrent expenditure, and because education and health care are intrinsically labour-intensive, this boost to pay will be expensive. State governments have limited taxation capacity and they would be reluctant to go further into debt to fund recurrent expenditure (that’s not good economics).

The most expedient solution would be for the Commonwealth, with agreement from the states, to raise the rate and scope of GST, because GST revenues flow to state governments. The effect of a higher GST would be slightly regressive, but the benefits in terms of health and education would be highly progressive in improving the social wage: overall such a move would be progressive.

The political implication – a forlorn Liberal Party

If Labor can hold its new working class in outer suburban seats, and if Labor, Greens and Teals can hold inner city seats, the future of the Liberal Party looks bleak, if it cannot have a strong urban presence in one of the world’s most urbanized countries. They have gotten themselves into this situation by their contempt for workers on the public payroll, and by their “small government” dogma.

Of course this wasn’t the only factor in the Liberals’ loss. Writing in the Saturday Paper Mike Seccombe provides a brief history of Liberal Party scandals in New South Wales. Premiers O’Farrell, Baird and Perrottet had high standards of public behaviour, but Seccombe’s account of the behaviour of some ministers and members of Parliament reads like a chronicle of political behaviour in Calabria – money laundering, donations from property developers, contracts and appointments for mates, and sexual behaviour that would be too offensive for Pornhub – are all on record.

Seccombe describes a view within the Liberal Party that sees political office not as an opportunity to advance the public purpose, but as a chance to distribute the spoils of political victory. If, as the Liberal Party asserts, all government activity is unproductive, then what does it matter how public money is spent – protection money to tame the gambling lobby, schools, contracts for political donors, police, glossy but useless projects in marginal electorates, roads? It’s all waste so why worry how it’s spent?

One clear winner – Newspoll

“It’s going to be a very tight race”.

That and similar comment was the standard way the media reported in the days before the election. Even the ABC stuck to that message.

In fact for some time polls had been predicting an easy Labor win, even though there was some tightening in the polls as the election approached.

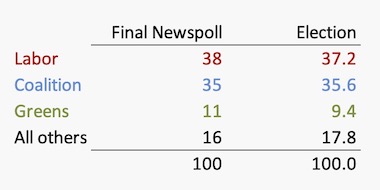

Newspoll, on the eve of the election, predicted a 54.5:45.5 TPP outcome in Labor’s favour. The actual outcome was 53.8:46.2: the comparison between Newspoll and primary votes is shown in the table alongside. All the Newspoll estimates are within a reasonable margin of error.

Yet the “tight race” story persisted. Perhaps the ABC is guided by some notion of neutrality. Perhaps the media in general like the tension of a tight race. That’s the way interest in a football match is sustained. But the outcome of an election has consequences; the outcome of a football game has none worth mentioning.

Many people, when voting, take expectations into account. If a win for one side is predicted some may want to join the bandwagon, while some others, wary about one side getting too strong a majority, may vote for the losing side. Perhaps there is some irrationality in both these behaviours, but if polling information is available there is no reason it should be withheld.

The Essential poll, a week before the election, showed that 41 percent of respondents believed that Labor would win, while only 35 percent believed the Coalition would win. Essential broke down responses by people’s voting intention: 75 percent of Labor supporters believed Labor would win, while 76 percent of Coalition voters believed the Coalition would win.

Those responses from Coalition supporters suggest that the election outcome may have been a shock for many true believers, even possibly contributing to a “we was robbed” belief, as has been the case with Trump’s supporters in the USA.

The media owe the public something better than the standard package of a junior reporter sent to the streets with a brief to find one Labor, one Coalition, and one undecided voter as a feed for the nightly news.