That wretched pardemic

Covid-19 is still with us

Last Saturday, March 11, was exactly three years since the WHO declared Covid-19 to be a pandemic. With the almost unique exception of smallpox, these pestilences never really go away. They slowly die down in a process of exponential decay, overlaid with a wave function, and sometimes suddenly come to vigorous life again.

As far as plagues go, Covid-19 has been one of the less deadly ones, probably because of the rapid development of vaccines. The Justinian Plague that kicked off in 541, hung around for a couple of hundred years, popping up in regions around the Mediterranean and killing more than half the people who contracted it.

Michael Toole and Brendan Crabb of the Burnet Institute trace the less spectacular progress of Covid-19 in a Conversation article: Three years into the pandemic, it’s clear COVID won’t fix itself. Here’s what we need to focus on next. Worldwide 7 million people have died – almost certainly an underestimate. In Australia almost 20 000 people have died with or of Covid-19.[1]

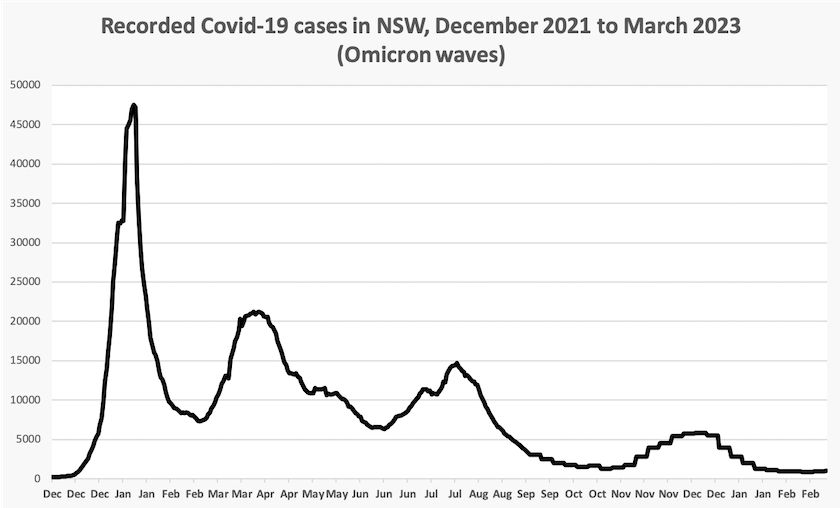

ABC data journalist Catherine Hanrahan has looked at the New South Wales data on new cases over the last 14 months, corresponding to the dominance of the Omicron variant.[2] Confirming other media reports she believes that these figures indicate that a new Covid-19 wave is in progress, but it is less severe than earlier waves. The graph below is generated from her data. It shows that the trajectory of this wave is close to tight conformity with the textbook equations of the reaction of a complex system to an external shock.

The Institute of Actuaries has estimated that in Australia in 2022 there were 20 000 more deaths than would have occurred had there been no pandemic. At first sight this does not reconcile with 20 000 deaths over the whole three years reported to the WHO, but the figure calculated by the actuaries is the number of deaths above trend, whatever the cause. Had the number of deaths been on an established trend there would have been around 170 000 deaths, but there were 20 000 more. They note that there were significantly more deaths from heart disease and diabetes, and “all other unspecified diseases” than would have occurred had our deaths been on trend, but there were significantly fewer from pneumonia. Also, many people who died withCovid died from other causes, and some who died from Covid would have died from something else in 2022. That’s unsurprising, because Covid deaths are mainly among people in their 80s and 90s.

We can construct speculative stories about causes for these excess deaths: perhaps it was difficult to get early diagnosis and life-saving treatment for some conditions – but there is not enough data to draw any conclusion, other than the general conclusion that Covid-19 has had system-wide effects. From the actuaries’ figures it appears that of the 20 000 estimated excess deaths about half were caused by Covid-19, and half were from other causes.

Michael Toole and Brendan Crabb in their article call for governments to be more forthcoming about Covid, to maintain public awareness of the threat of long Covid, and to urge the public to keep up with vaccination and exercise sensible public health behaviour.

1. 19 447 according to the figures our governments report to the WHO. ↩

2. New South Wales maintains and publicizes a great deal of data on Covid-19 in their Health Department’s weekly respiratory surveillance reports. By now the data from most other states is scrappy. ↩

Covid-19’s origin – somewhere to our north

The question about the origin of Covid-19 is still unresolved. There are still extremists asserting that the Chinese government unleashed it as a biological weapon – an assertion with no support in logic or evidence. The disagreement among adults is whether it resulted from animal-to-human transmission or an accidental laboratory leak, most probably from the Wuhan Institute of Virology.

Patrick Walsh and Ausma Bernot, of Charles Sturt University, in a Conversation contribution, examine the way US intelligence agencies went about the task of tracing Covid-19’s origins. Those agencies were under pressure from the Trump administration to lay blame for the outbreak on the Chinese government.

The intelligence agencies all agreed that Covid-19 was not an incidence of bioterrorism, but otherwise their assessments conflicted. Notably scientists have been more likely than the intelligence agencies to believe that the origin was in a wet market. But are scientists biased in this regard, being more inclined to put their faith in other scientists than in public health regulators?

The authors conclude that the intelligence agencies were not up to speed in their capacity to detect, analyse and assess biological threats. They need to develop better ties with the scientific community and to develop their capacities in microbiology, genetics, virology and public health. In general countries need to develop national health security strategies. Covid-19 will not be the last worldwide biological threat.