Macroeconomics

Is the RBA run by a one-line computer code?

After the tenth interest rate rise, many Australians may have reason to believe that the Reserve Bank is exercising little human judgement in its monthly interest rate decisions. Is it relying on some automated process? Perhaps the code reads something like this:

IF X > K, ΔR = 0.025, where X is the latest ABS monthly CPI estimate, K is the bank’s beloved two to three percent inflationary zone, and R is the cash rate.

Of course the bank’s decisions involve deliberation, revealed in its painstakingly detailed statements issued each Friday after its decisions. But the call from unions, businesses and many independent economists is to suspend the supposed automated process for a while and observe what’s happening. The only people finding any joy in rising rates are the federal opposition, whose deputy leader blames the Albanese government for the Ukraine war, the Covid-19 pandemic, and nine years of Coalition economic mismanagement.

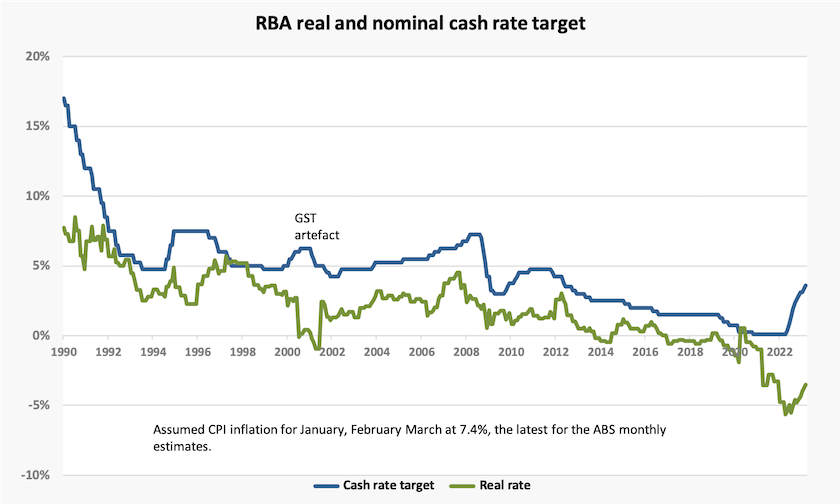

The graph below incorporates the latest interest rate rise. The green line, showing real (inflation-adjusted) interest rates, suggests it is still negative, but strictly the real rate relates to expected inflation, not inflation as it has been most recently recorded.

According to the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research, current inflationary expectations are around 5 percent, having fallen in recent months. That still leaves us with a negative real interest rate of about 1.6 percent, but it doesn’t mean that nominal rates have to go on rising to bring real rates back to positive territory. If inflationary expectations are falling the real rate will get there in time.

The RBA’s press release is largely predictable, but is less categorical about future rate rises. Peter Martin is among economists who read into the Bank’s statement a strong hint that it may be considering only one more rise in rates. The Bank acknowledges that inflation may have peaked: the January CPI indicator shows that CPI inflation peaked in December: the January CPI was actually 0.4 percent lower than the December CPI.

If one could rely on one month’s data – and there are solid mathematical reasons one should not – one could assert that inflation is now negative. But the point is that the Bank’s choice of year-on-year CPI movements as an indicator of inflation is an arbitrary choice. Furthermore, the CPI is an indicator only of household consumption inflation, not of economy-wide inflation. The GDP chain price index for the December quarter, an indicator of economy-wide prices, was only 0.6 percent higher than the index for September, suggesting an annualized inflation of 2.6 percent – right in the RBA’s target zone. Again, there are problems associated with the GDP deflator, because it is influenced by the terms of trade, but the more general point is that the RBA, from its press statements, appears to many to be relying on one indicator, the CPI over the previous 12 months, even though it has well-qualified staff who would be well aware of the risk of relying on one indicator.

A conspiracy theorist would claim that the RBA, in order to justify its role, has an interest in finding indicators of inflation, even to the extent of nudging inflation along, like the firefighter who turns arsonist.

That’s because higher interest rates work not only to suppress demand: in some areas they actually drive up prices. For example the Bank notes that “rents are increasing at the fastest rate in some years, with vacancy rates low in many parts of the country”. So the monetary solution is to raise interest rates, which will flow through to rents, which will reflect in a higher than otherwise CPI. In industries where firms have strong market power, companies will treat higher interest rates as a cost to be passed through to consumers in the form of higher prices, particularly if reduced demand means they do not benefit from scale economies.

The problem lies not with the Bank, but with monetary policy itself, designed around an idealized frictionless and competitive economy, with easy movement of capital and labour.

The world is more complex than that, and “much of today’s inflation is not well understood” to quote from an article in the IMF Finance & Development journal – The very model of modern monetary policy – by Greg Kaplan, Benjamin Moll, Giovanni l Violante. Because price rises have different effects on different parts of the economy, and because conventional monetary interventions also have different effects (such as the effect on rents illustrated above), monetary policy as currently practised is a costly way to stabilize the economy, resulting in a great amount of collateral damage. If you ask a tradesperson to renovate your house, using only a chain saw and a sledge hammer, don’t expect an optimal outcome.

The authors suggest that rather than operating in different institutions with different instruments, monetary policy and fiscal policy should work hand-in-hand with considered interventions in different parts of the economy.

That’s hardly radical, because it is about the efficient allocation of scarce resources, a basic objective of conventional economics, but it implies a change in institutional ways of working and a change in thinking.

Ross Gittins makes much the same point as the IMF authors in his post RBA inquiry should propose something better. He points out why monetary policy with its one big lever, is so inept at dealing with economic problems, and in some markets, such as housing, can aggravate existing problems. He suggests that governments could place fiscal instruments into the hands of institutions with delegated power, at arm’s length from government, to apply stabilizing pressure on parts of the economy. JK Galbraith suggested something similar many years ago, when he put forward the idea of an independent body that would set the rate of unemployment benefits in response to labour market conditions.

In case you missed it – productivity is back on its dismal trend

Everyone was so obsessed by the poor growth revealed in last week’s National Accounts for the December Quarter that they missed two of its important revelations. One is that per-capita real net disposable income is barely moving. That indicator, derived from national accounts, nets out the effects of population growth and income flowing to foreigners, thus giving a first-order estimate of households’ material welfare. John Hawkins of the University of Canberra presents this and some other interpretation of national accounts data in The Conversation.

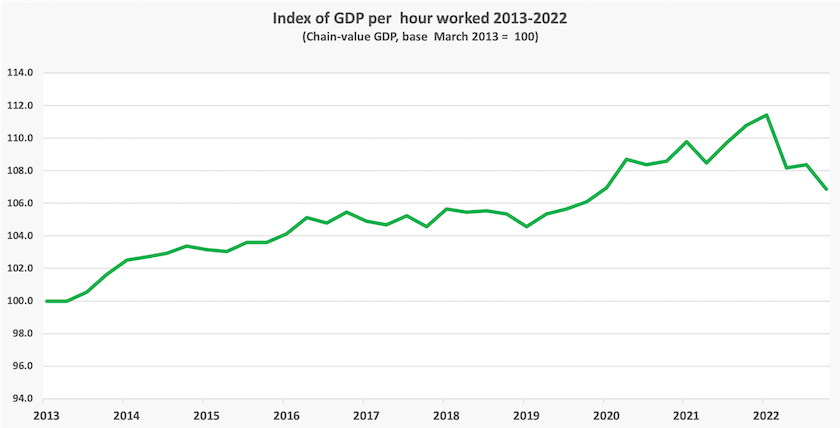

The other important revelation from the national accounts is that productivity is not improving. Labour productivity, as indicated by the ABS series on GDP per hour worked, has fallen once again, as shown in the graph below. It is now headed back to its stagnant level over the 2016-2019 period.

It is unsurprising that productivity rose during the Covid-19 downturn. That’s a normal textbook response to recessionary conditions: theory predicts that the least productive workers lose their jobs in a recession, thus boosting productivity indicators for a while. Also, stimulus payments in response to Covid-19 boosted GDP in ways that do not happen in normal government counter-cyclical spending.

Almost any economist, left or right, will assert that without rising labour productivity there can be no sustainable rise in real wages. Over the 6 years from early 2014 to late 2019 – the Coalition’s time in office before Covid-19 – GDP per hour worked had risen 3.5 percent – a little less than 0.6 percent a year. That poor performance explains a great deal about the lack of real wage growth we are now experiencing.

Superannuation – is fanatical scaremongering the best the Coalition can do?

True to form the Coalition, in opposition, has made a very loud noise about a very minor tweak in superannuation – a tweak that does nothing to take away superannuation’s capacity to provide a decent income in retirement, but which does help prevent superannuation from becoming a government-subsidized vehicle for the rich to establish family dynasties.

Angus Taylor has asserted that because the $3 million accumulation threshold is not indexed, in time the average Australian worker will have accumulated $3 million: you can read a transcript of his interview with David Speers which he has mounted on his own website.

To look on the bright side, perhaps Taylor is starting to think of the long-term consequences of government policy, a perspective that escaped him when he was Minister for Energy and Emissions Reduction.

As reported to the Sydney Morning Herald’s David Crowe, Grattan Institute economic policy director Brendan Coates, drawing on the Institute’s modelling, projects that it will not be until 2052 that the top 10 percent of Australians will be retiring with nominal superannuation balances of around $3 million. The only logical explanation for Taylor’s concern is that he assumes the Albanese government will still be in office in 2052 – a possibility to which he and his Coalition colleagues are contributing with their puerile behavior.

As we pointed out in the roundup two weeks ago, Chalmers’ change to superannuation, while in the right direction, is still ridiculously generous. Brendan Coates and Joey Moloney, also of the Grattan Institute, not only argue for a $2 million threshold, but they also argue for a reduction in tax concessions for superannuation contributions made by people with high incomes, while they also put the case for a little more tax incentive for low-income earners to contribute to superannuation.

Politically, people don’t seem to be taking too much notice of Taylor’s scaremongering. William Bowe draws attention to the most recent Newspoll, reporting that 64 percent of those surveyed support the government’s changes, while only 29 percent are opposed. Similarly the Essential Report goes into detail about superannuation: they find only 19 percent of respondents are opposed to the government’s change. Essential puts to respondents a number of statements about the government’s intentions on superannuation and asks whether they agree. For example, 58 percent of respondents agree with the statement “They want to ensure that the purpose of super is to help people save for retirement, and stop it being used as a tax shelter for the rich”. Only 14 percent disagree with this statement. They get similar responses to the statement “They are trying to find additional money to pay down debt and improve services like aged care and health”. Overall, respondents seem to have a reasonable grasp on superannuation and fiscal policy.

They throw in two questions with a partisan bait: “They want to penalize people who work hard and are successful”, and “They are trying to trick people into accepting changes to super, which they promised not to make”. There are clear partisan divisions on these statements, with which a majority of Coalition supporters agree. It’s amazing how some people can attribute an inheritance, luck on the stock market or real estate market, a favorable tax ruling, or a job in a privileged industry sector, to their own effort.

Essential also asks people how much they believe they have in superannuation, with breakdown by age, gender and voting intention. People seem to be reasonably well aware of their situation: their responses generally line up with APRA data. Women are in no doubt that they have less in superannuation than men. Research published by the Australia Institute on Wednesday shows that over their working lifetimes women earn $136 000 less than men in superannuation. That’s because women have more broken employment and have lower-paying occupations than men.

Paul Keating would be pleased to know that people are paying attention to superannuation. But there is the possibility that people’s awareness of their own balances has been stimulated by feelings of financial insecurity, and a fear by some that they may have to seek early access to superannuation.