Transport policy

A clunky shift to electric vehicles

The media recently ran a story about David Farrands, a retired schoolteacher from Victoria, who was driving around Tasmania in his electric vehicle. He had to pay 2.1 cents per kilometer travelled because his vehicle is registered in his home state, and Victoria has an electric vehicle road user charge scheme. Farrands was annoyed, and no doubt the Tasmanian government would be annoyed by this arrangement.

Even those who never take their EVs out of Victoria are so peeved by Victoria’s road user charge scheme that they are trying to bring a challenge to the High Court. For EV owners the issue is about conflicting incentives for people to buy EVs. Most states and territories, including Victoria, have small concessions on registration fees for EVs, and the Commonwealth has an indirect incentive exempting EVs from fringe benefits tax – the tax that applies to employer-provided fringe benefits. The EV road user charge scheme seems to send a conflicting message.

The legal issue is about whether Victoria’s charge-per-km scheme is a “user charge” or an “excise”, because under Section 90 of the Constitution, only the Commonwealth is permitted to impose “duties of customs and of excise”. Other states are lining up on Victoria’s side.

The general issue is about Commonwealth-state fiscal relations. Although only hinted at in our Constitution (Section 96), Australia has a strong tradition of the Commonwealth collecting taxes and redistributing revenue with consideration of states’ needs and the benefits of uniformity. In this regard the Grants Commission, set up in 1933, is the most significant institution giving effect to this principle. In 1942 the states effectively ceded income-tax powers to the Commonwealth, and the GST agreement struck in 2000 essentially involved the Commonwealth collecting GST on behalf of the states. These are the arrangements and agreements that have allowed us to avoid the competitive race to the fiscal bottom that we observe in the US.

So the decision by some states to set road user charges is about more than annoying holidaymakers travelling interstate or annoying the Tasmanian government. Few people would suggest that in time users of EVs should not pay for the roads they use, but is this the way to go about it?

At least Victoria has done the nation a service in illustrating the difficulty in charging for EVs. Its requirements are absurdly clunky: every year, on July 1, EV owners are supposed to photograph their odometers and keep records for five years. And, in line with that state’s tradition of parochialism, the scheme assumes Victorians never drive interstate or that others never drive in Victoria. The problems down the track for their road user charge scheme will make the Commonwealth’s Robodebt look like a minor administrative error. Collectively we need to do something more intelligent to fund our roads.

For now, if Australia is to meet its emissions targets, and reduce urban air pollution, priority has to be given to the uptake of EVs – not just cars but also commercial vehicles which are by far the bigger problem. Hassan Dia of the Swinburne University of Technology, writing in The Conversation, argues why a shift to basing vehicle registration fees on emissions matters for Australia. In comparison with other countries our uptake of EVs has been slow and we are laggards in shaping transport taxes and charges to assist in the process.

As with many emissions-reduction problems, the simplest policy pathways often have adverse equity outcomes. In comparison with internal combustion (IC) vehicles, and with hybrids, electric cars are expensive, starting at about $50 000, or about twice the price of the cheapest IC cars. As Andrew Moseman points out, writing in The Atlantic, in the US electric cars have become status symbols. In his article, The inconvenient truth about electric vehicles, he shows that EVs have become means for the well-off to engage in virtue-signaling. (Think of the feeling when you’re stuck in a clogged freeway in Los Angeles and see Teslas hurtling past in the left lanes.) An electric car is ideal for the well-off suburbanite with a free-standing suburban house with a roof covered in panels.

That’s why the Commonwealth’s fringe benefits tax exemption for EVs makes some sense, because the benefits will pass through to households once these vehicles are sold on the used car market. It’s a pragmatic use of trickle-down economics, but it goes against the more basic principle of discouraging paternalistic employment arrangements, which is the whole purpose of fringe benefits tax.

Similarly, while fiddling with registration fees makes some sense, there is little justification for our high fees for motor vehicle registration and compulsory third-party insurance – a form of privatized taxation. These are charges on vehicle ownership, not on motor vehicle use. It’s the use of motor vehicles that contributes to costs of congestion, wear on roads, accidents, and emissions from IC vehicles, and in the interests of allocative efficiency registration fees should cover no more than the cost of maintaining a registry, while other costs should be picked up in per-kilometer or similar charges such as a higher excise on gasoline and diesoline.

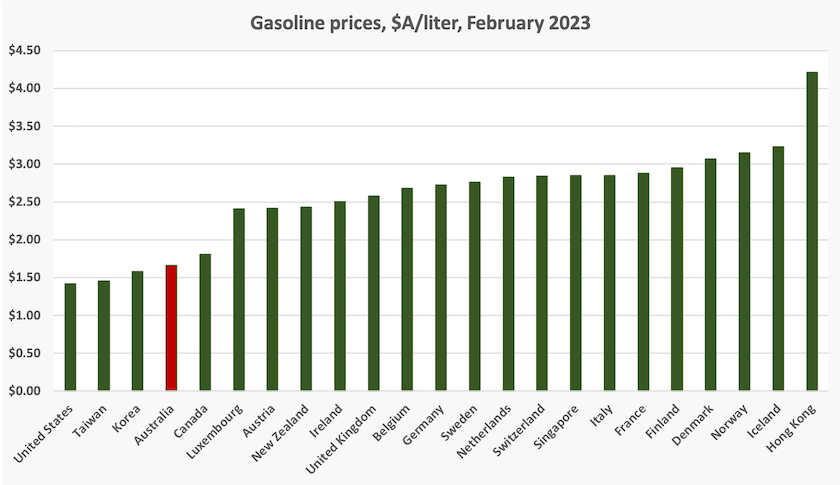

That is hardly a novel idea, but the reason it doesn’t happen is political. The states want to hang on to registration fees, and the Commonwealth, during the long periods of Coalition government, has been sensitive to demands from the National Party to keep fuel prices low, disregarding our highly-urbanized settlement pattern. Our gasoline prices are close to the lowest among all prosperous “developed” countries.

If EVs follow the path of other technologies, with a sudden (logistic) uptake, there could be a shock to Commonwealth excise revenue, presently set at 47.7 cents a liter and budgeted to raise $6 billion from gasoline and $13 billion from diesoline.[1] Even before there was much consideration of electric vehicles, the Productivity Commission, in 2017, was warning that revenue from fuel excise was in long-term decline, in large part because of improved vehicle fuel efficiency.

There will need to be some sensible way to have users of EVs pay for road use. That may provide an opportunity to use prices related to road use rather than to vehicle ownership.

No EVs out here yet

Ideally any review of road user charging should address the economic distortions created by the presence of toll roads in Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane. These are high-quality roads, generally well separated from local roads (particularly when they’re underground), and at most times with vehicles running at speeds which minimize emissions. A pricing system designed to maximize their environmental and travel-time benefits would apply an incentive for their use, or a penalty for rat-running through suburban roads. But because tolls are in addition to vehicle excise, the economic incentives are in the opposite direction – a case of what economists refer to as “deadweight loss”, a loss in which no party benefits. A road pricing reform designed around principles of allocative efficiency and equity, rather than financially convenient ways to fund infrastructure off-budget, would place a high price on road use at places and times with high negative externalities. That would see costs more fairly distributed, without the need for governments to cobble together compensation payments for those who are frequent users of toll roads.

1. Budget Paper 1, Table 5.8.↩

Fuel tax credits

Which of these vehicles should pay for roads and GHG emissions?

It is easy to demonstrate that our taxation laws privilege the mining industry. One target for critics is the fuel tax credit scheme, which provides a reduction or exemption from fuel excise for certain heavy vehicles and for off-road use, estimated to cost $8 billion this year rising to $11 billion by 2025-26.[2] On its website the Australia Institute has a short outline of the cost of the scheme, pointing out that about half of the benefit goes to the mining sector.

But fuel excise, while it is not formally a hypothecated tax, roughly equates to expenditure on roads as pointed out by the Australian Automobile Association.[3] Mining companies using fuel at mine sites and on their own roads and railroads can legitimately claim that they should not be paying for public roads. Farmers and fishers can legitimately make the same claim.

The complexity around fuel tax credits is explained in a research paper by the Grattan Institute: Fuelling budget repair: how to reform fuel taxes for business. It goes into the history of fuel excise and other sources of government revenue that relate to transport, and a detailed explanation of how those taxes and charges currently apply. If you read the paper don’t expect to find any underlying set of principles or consistent policy logic in our present arrangements.

The report draws attention to a set of decisions by the Howard government to allow fuel tax credits, with a partial exemption from excise, for trucks heavier than 4.5 tonnes. That’s right, heavy trucks, right up to 42 tonne semi-trailers, pay less for diesel fuel than light delivery vehicles, even though the wear on roads rises disproportionately with axle load. (For a given axle configuration a truck of double the weight produces about 15 times the road wear. Road wear is particularly severe where trucks have to brake, such as at intersections as the full energy of deceleration is absorbed by the road.)

While the authors find it difficult to make sense out of the scheme as it has developed, they advocate a simple and economically coherent policy approach. There would be three taxes on transport fuels: the GST (as it currently applies to final household use, levied at the pump, as at present), a charge for environmental externalities, mainly relating to greenhouse gas emissions (which all fuel users would pay), and a road user charge (which would not be paid by mining companies, farmers, fishers and other non-road users). With removal of the Howard concessions there would be some higher fuel cost for trucks – around 4 percent for B-doubles and road trains, and less for lighter vehicles. These would pass through to household budgets but only in a very small way – and that’s without estimating savings to households that would arise from less damaged roads: suspensions and tires are expensive.

In time the revenue will fall away as fossil fuel use falls away. The writers estimate that it will be 2040 before all new rigid trucks are electric and it will be some time after that before all new articulated trucks are electric. There will be a faster switch to electrification for cars and light trucks, and they will need to be subject to some user charge – something more intelligent and more aligned with current technology than photographing one’s odometer every July 1.

2. Budget Paper 1, Table 6.3.1. ↩

3. The graph on the AAA website shows net excise revenue, after the cost of fuel tax credits is deducted, which it why it does not align with budget papers.↩

Road trauma

When the media is always on the lookout for failures in public policy, governments’ achievements get very little press, particularly when those achievements are slow and incremental over a long period.

In 2021 there were 1123 road crash deaths in Australia. That’s 44 fatalities per million people. In 1981, 40 years earlier, there were 223 fatalities per million people. Had there been no improvement over those four decades, there would be about another 5000 lives lost due to road trauma every year.

Better roads, safer vehicles, drink-driving laws, more effective policing, and more carefully selected speed limits have all played their part. Most of this improvement is due to specific government programs in funding, regulating and enforcing, but vehicle manufacturers have also played their part.

That’s not the complete story however, and since 2018 there has been an increase in fatalities involving articulated trucks – a classification that includes semi-trailers, B-doubles and road trains.

This rise in deaths coincides with a decision in 2016 by the Coalition government to abolish the Road Safety Remuneration Tribunal, a body established in 2012 by the Gillard government to set minimum pay for truckers, including owner-drivers, in an effort to stop a competitive race to the bottom as truckers, desperate for business, would skimp on maintenance, break rules on driving hours, and break speed limits, in order to stay in business. The Minister for Employment, Michaelia Cash, in justifying its abolition said: “We will always stand up for enterprising small businesses who dare to take a risk and invest in themselves and their families to get ahead.” When she referred to “risk” perhaps she was thinking about normal business risk, but the risk faced by truck drivers and innocent people sharing the road with sleep-deprived and stressed drivers is deadly.

Writing in the Sydney Law Review at the time – Compromising road transport supply chain regulation: the abolition of the Road Safety Remuneration Tribunal – Michael Rawling, Richard Johnstone and Igor Nossar praised the Tribunal as having developed “a worldleading initiative for regulation of the road transport industry”, and they concluded with a comment on its demise, a victim of a media scare campaign and right-wing economic dogma:

The industry and media furore over the 2016 RSRO [the Contractor Driver Minimum Payments Road Safety Remuneration Order] … shows how volatile the implementation of innovative workplace regulation can become and how things can quickly turn against progressive reform when a conservative government acts with zeal and opportunism to counter such regulation. This is so where the right wing and conservative media fuels a campaign against such regulation. This goes some way to explaining how the public debate about the Tribunal, which began with criticism of a particular tribunal order, quickly turned into an almost unstoppable groundswell to abolish the Tribunal. The role that ideology plays in the making and unmaking of workplace legislation is also particularly highlighted by the fact that concerns raised in the public debate over the 2016 RSRO may have never eventuated and, in any event, could have been addressed by delaying and amending the Order.

The Albanese government seems to intend to re-establish, within the industrial relations framework, measures to prevent a race to the bottom by owner-drivers. In a speech on February 1, Tony Burke said:

… in an industry like road transport, setting standards in road transport can be about survival. Survival of transport workers whose workplace is the road, survival of families who share those roads, and survival of an industry integral to our economy. In all corners of the industry, unregulated supply chain pressures and the seismic insurgence of the gig economy have caused the perfect storm, which is taking lives, jobs, and businesses. We've had too many stories of horror from every sector of transport where cost-cutting and unrealistic deadlines have gone unchecked.

In the same speech he posited systems of protection for workers in the gig economy and other situations of self-employment which would ensure they share some of the important protections enjoyed by employees on the payroll, without compromising their autonomy.

So far, however, we haven’t heard much about any further progress. On February 7 Catherine King, Minister for Transport, Regional Development and Local Government, announced a National road safety action plan to reduce road trauma, but it makes no mention of any initiative to prevent a competitive race to the bottom. It devotes a page to heavy vehicle safety, with reference to useful initiatives such as fatigue detection technology and construction of more heavy vehicle rest areas, but there is nothing about reforms that will allow owner-drivers to be assured that they are not at risk of losing their livelihoods by being undercut by desperate competitors who are indifferent to their own or others’ safety.

Silent killers on our roads

Once tetraethyl lead was phased out in 2002, and as regulations have progressively reduced the sulfur content of diesoline, local air pollution effects of transport seem to have gone off the agenda.

Melbourne Climate Futures, a research centre within the University of Melbourne, in a brief press statement has warned that vehicle emissions may cause over 11 000 deaths a year. That compares with around 1 000 deaths a year directly attributed to road accidents. They draw particular attention to the omission of nitrogen oxide (NO2) emissions from previous estimates. They also mention fine particulate matter, which is a hazard from old and poorly-maintained diesel engines. In their press release they state:

While every other country in the OECD has standards for the amount of pollution new vehicles can emit, Australia has some of the most polluting vehicles in the world.

Australia is the only OECD country without new vehicle carbon dioxide standards and lags a decade behind European standards for fuel quality and vehicle emissions.

Melbourne Climate Futures provides no further information to back up these strong claims. It is important for policymakers to know the specific sources (diesel or gasoline?) whether they relate disproportionately to old vehicles, whether there are areas of particularly concentrations (tunnels, city streets with stop-start traffic?), and, in the case of trucks, whether they relate to light or heavy trucks, because heavy trucks with diesel engines will be on our roads much longer than light trucks and cars. But we do know that our reluctance to strengthen our emission standards is one reason manufacturers are finding Australia a ready market for vehicles that don’t meet European standards.