Economics

Tax expenditures – $250 billion of concessions under scrutiny

Media coverage of a minor modification to superannuation concessions has overshadowed the more significant posting of the Treasury’s 2022-23 Tax Expenditures and Insights Statement. This looks like becoming an annually-produced fiscal document, adding to the already-established Budget and the Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook.

“Tax expenditures” are basically revenue the government forgoes because of concessions to particular groups, or lower taxes applied to types of income. The definition of “tax expenditure” is loose. For example, is a tax-deduction for work-related expenses a “concession” or simply an acknowledgement of an established definition of “income”?

Major tax expenditures have always been included in Budget Paper 1, but without analysis or explanation. This new document is a reclassification, a recalculation of their budgetary cost, and a detailed analysis of 21 of the 57 classes of tax expenditures, with estimates of the distribution of benefits by income decile and in some cases age, gender and other classifications.

The document, free of political spin and free of normative statements about the desirability or otherwise of tax expenditures, looks like yet another supplementary budget document, prepared by public servants as mechanical fiscal analysis. But there is a message in the choice of the 21 items subject to detailed analysis. Why, for example, is the exemption of capital gains tax for one’s main residence, the largest of all tax expenditures, not included? Why is dividend imputation classified as a “tax expenditure” when it is simply a refund of tax paid? Why is the Medicare Levy Surcharge treated as a penalty for not holding private health insurance, implying that Medicare is a program of distributional charity rather than a universal scheme? (See a more detailed consideration of this within this roundup under “Health policy”.)

That is not to suggest that the government has had some “left” or “Labor” influence on the document. If there is an ideology implicit in the document it’s the ideology of “budget repair”. That is, a search for opportunities to close revenue gaps, prioritizing fiscal bookkeeping over considerations of allocative efficiency – a continuation of the Coalition’s approach to economic management.

On Wednesday night’s 730 Report Allegra Spender criticized the government for the approach it has taken – listing a large number of tax concessions and making a minor change to just one of them. As others including Ken Henry have said in the past, a serious discussion on tax reform should put everything under scrutiny – even sacred issues such as the tax-free status of the family home. A piece-meal approach, responding to political pressures and media demands to rule out specific changes, is a poor way to handle public revenue.

Spender’s carefully-considered criticism contrasts with the petulant outcries by Angus Taylor and other Coalition members, defending the idea that taxpayers should subsidize the well-off in their accumulation of family fortunes. Peter Martin, writing in The Conversation, sees the government’s tweak to superannuation as another undoing of the Howard government’s concessions on superannuation – concessions so irresponsible that Scott Morrison, when he was Treasurer, started winding them back in 2016, when he put a cap (then $1.6 million) on the account balance from which retirees could draw tax-free income. The present government’s change is simply an extension of that approach.

Comments on some of those 21 items, using the document’s headings, follow below.

Concessional taxation of superannuation contributions, and Concessional taxation of superannuation earnings

In view of the $50 billion cost of superannuation concessions, the government’s reform, involving savings of about $2 billion a year, is underwhelming. Most commentators expected that the Treasurer would set a limit on the amount that could be invested in a retirement account enjoying any concessions on earnings. Such a cap would require any amount above the cap to be held as a personal investment, with earnings subject to individual tax rates, reasonably assumed to be the top 47 percent marginal tax rate for anyone who has managed to accumulate $3 million of more in their superannuation account. But instead the government reform has introduced another concessional band, 30 percent.

It’s hard to explain the government’s caution, unless it’s because of memories of the Murdoch media’s deceptive misrepresentation of the Rudd government’s attempt to reform resource taxes, and their hysterical treatment of Labor’s proposals in the 2019 election campaign. As Allegra Spender suggested on her 730interview, we should not assume that everyone presently enjoying an unwarranted tax benefit will object to its withdrawal. (Why do journalists and Coalition politicians assume that everyone who is well-off is opposed to tax reform and will greedily defend undeserved privilege?)

It is notable that in comparison with the estimates prepared for the budget last year, which saw little growth in the cost of superannuation contribution concessions, this analysis projects a sharp growth in the cost of those concessions, while estimates for the cost of concessions on superannuation fund earnings are little changed. It is a reasonable guess that Treasury is less concerned with the immediate cost of earnings concessions, and is more concerned with people’s plans to use superannuation contribution concessions to accumulate large fortunes. They want to head off those plans. This gives the government enough political cover to supposedly break a promise, and to be relaxed about the date of implementation.

Politically, as Crispin Hull points out, the Opposition may squeal, but it has no moral or economic leg to stand on. “The Coalition’s attitudes to superannuation over the past 40 years are replete with hypocrisy and class warfare” he writes.

Capital gains tax discount for individuals and trusts

Unsurprisingly the 50 percent tax discount on capital gains is identified as the next big item ($24 billion this year), with 75 percent of the benefit going to those in the top income decile.

Because this is only a fiscal analysis, concerned with short-term taxation revenue, the document fails to point out that the capital gains tax system, introduced by the Howard government, far from giving a concession actually penalizes those who make long-term patient investments. That’s because, unlike the system Howard and Costello abolished, it makes no allowance for inflation. The capital gains tax system developed by the Hawke-Keating government applied a 100 percent rate of tax, but only on real gains. The Howard-Costello “reforms”, implemented in response to the finance sector’s lobbying, were specifically designed to encourage financial “dynamism” – a euphemism for “speculation”.

The way Treasury has presented the capital-gains concessions is disappointingly superficial, and seems to be more about short-term revenue concerns rather than an economically efficient approach to capital gains taxation.

GST exemptions for food, GST exemptions for education and GST exemptions for health care

Among many commentators it is an item of economic faith that food should be exempt from GST. But Treasury’s analysis demonstrates that the higher one’s income, the more are the benefits of this exemption. It’s a regressive exemption, because it applies to fillet steak and macadamia nuts as well as to flour and milk.

Not all food is created equal

The exemption for education is even more regressive, with 27 percent of the benefit accruing to the top income decile. That’s because it applies to fees for indoor equestrian centres and the upkeep of lavish grounds and school buildings (using a little accounting creativity) at private schools.

Health care GST exemptions are also regressive. At first sight that’s surprising, because the poor and the old are disproportionately high users of health care, but it’s because many health care services, even though they are therapeutically beneficial, are not covered by Medicare. Dental surgery is the most significant example, but so too are many services relating to mental health and rehabilitation. Although it would be out of character for Treasury to suggest it, its analysis supports a case to expand Medicare to cover more services.

In these three bits of analysis Treasury builds the ground for abolishing GST exemptions, particularly for food and education. What defenders of these exemptions miss is that while their abolition may be regressive, such regressivity would be more than compensated for by the increase of revenue flowing to the states. That’s because GST revenue flows to the states, and between 50 and 60 percent of state governments’ recurrent expenditure is for health care and education, with distributional benefits. Tax reform will succeed only if we look at taxes as a whole, rather than at specific items that we like or dislike.

Franking credits received by individuals

It is hardly a surprise that Treasury finds that 88 percent of franking credits are received by individuals in the top income decile. These are the people most likely to invest in private and public companies.

What is surprising, however, is that franking credits should be considered as taxation revenue forgone, because they are simply a refund of tax already paid. They are no more a concession than is a refund of tax received by a PAYG taxpayer who has been employed for only part of the year. It’s as if Treasury’s collective memory has forgotten about the economic basis for our company tax system, articulated in the 1975 Asprey taxation review, and implemented by the Hawke-Keating government.

Dividend imputation allows Australia to maintain a high rate of corporate tax applying to outside investors (30 percent), while effectively allowing Australian investors a much lower tax rate, in the order of 15 percent (depending on the company’s payout ratio), which is around the average for OECD countries. It encourages small investors to put their savings into Australian companies and to share in the nation’s growing real wealth, rather than into bank deposits or housing speculation. And it encourages companies to pay out profits as dividends, which can work against monopolization.

In classifying dividend imputation as a “tax expenditure” Treasury seems to be more concerned with the cosmetics of short-term “budget repair” than with the allocative effects of our company tax arrangements.

Rental deductions

As Treasury points out, “rental property investors can claim deductions for expenses associated with maintaining and financing property interests. These include interest, capital works and other deductions required to maintain their rental property”.

It’s an expensive allowance, costing public revenue $4 billion a year. That’s largely because of generous and unjustified concessions introduced by the Howard government encouraging people to speculate in real-estate, but Treasury isn’t going to make that point.

The statement by Treasury describing the deduction, quoted above, contains a fundamental accounting error, because it allows deductions not only for providing a rental property but also for financing it. That involves a degree of double-counting, particularly when there is inflation, which means property speculators are over-compensated for their expenses.

Demonstration of this effect requires the use of some Year 12 math, a whiteboard, and a class motivated by the realization that life-cycle costing will probably be on the exam paper. Treasury staff would be well aware of this problem, but they have glossed over it.

Cost of managing tax affairs and other deductions

This isn’t one of the biggest ones: it’s estimated at only $1.6 billion a year. But the telling aspect is that around half of this allowance – $800 million – has been claimed by almost a million taxpayers in the top income decile. That’s $800 a head for that group, who can afford professional advice to find tax lurks and loopholes – a reflection of the complexity of our tax system and the influence of lobbies. It’s also an exposure of a part of our unproductive transactional overheads, costing $1.6 billion a year, using the services of skilled and highly-educated people who should be better employed doing something with real value-added.

In all, the Tax Expenditures and Insights document misses an opportunity to contribute to taxation reform. Rather, it seems to be focused on the short-term fiscal bottom line, a continuation of policy of Coalition governments who have prioritized fiscal impression management over economic structural reform.

The Australian economy in three snapshots

The first is a 13-minute clip – Debt nation – on the ABC’s 730 program, in which Alan Kohler explains:

- macroeconomics as taught as universities, including the wonderful theories of the Phillips Curve, and the NAIRU (he attaches words to this weird acronym);

- how this model is embraced by staff and the board of the Reserve Bank, and by the economics establishment generally;

- how the model does not provide useful policy guidance for an economy with low unemployment, falling wages, low or negative real interest rates, high household debt and over-priced assets, particularly housing.

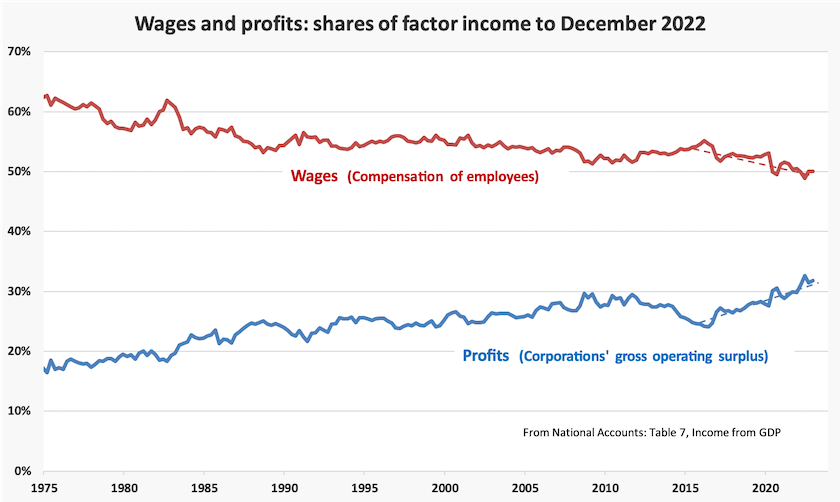

The second is Ian Verrender’s explanation why company profits are soaring to new heights as Australian wages can only crawl higher. It’s about the market power exercised by the few corporations occupying crucial parts of our economy. Two, three, or even four firms in any sector do not necessarily provide sufficient competition to prevent firms from enjoying excess profits. It’s not about collusion, but rather it’s about the dynamics of oligopoly. When a small group of firms happens to have similar non-competitive prices, there is no benefit, other than a transient first-mover advantage, to a firm that breaks ranks by offering competitive prices.

The third snapshot is provided by the ABS National Accounts, released on Wednesday. They paint a dismal picture. Economic growth in the December quarter was only 0.5 percent. But for a 4.3 percent fall in imports, there would have been zero economic growth. In spite of high corporate profits, business investment fell, and the household saving ratio fell. There is some indication of inflation – the GDP implicit price deflator rose by 1.6 percent – but there is no indication that the economy is overheating. It is beyond belief that the Reserve Bank should even be thinking about raising interest rates when it meets on Tuesday.

The national accounts confirm that movement of factor income from wages to profits has continued its trend.

At what stage does such unfairness reach a point where people lose faith not only in the incumbent government, but in the whole political system? Is our fifty-year passive acceptance of widening inequality preparing the ground for populist demagogues with their simplistic solutions to take the political stage?

Industry policy reconsidered

The term “industry policy” evokes memories of Holden cars, Pelaco shirts and Simpson washing machines, all made in Australia, and protected from competition by tariffs and other import barriers.

In its time such an industry policy served us well, but it lived on past its use-by date, until the Hawke-Keating government, in a series of reforms, opened up the Australian economy. Although there are now reasonable concerns about self-sufficiency in certain areas, no one is seriously suggesting we should return to policies to sustain employment by privileging certain industries – generally manufacturing – through ongoing subsidies such as tariffs, import quotas and direct subsidies. Indeed, because of its association with such measures, many economists scoff at any suggestion that a government should have an “industry policy” at all.

The Albanese government does have an industry policy however, in the form of the $15 billion National Reconstruction Fund, which it is presently steering through the Senate.

If we look at its seven priority areas we won’t find “cars”, “shirts”, or “washing machines”. Rather the emphasis is on technologies and capabilities, and there is no singling out of manufacturing.

On last weekend’s Saturday Extra, Geraldine Doogue’s two guests, Jens Goennemann of the Advanced Manufacturing Growth Centre and Louise McGrath of Australian Industry Group, explained how they believe the NRF can play a crucial role in Australia’s economic recovery: Transforming industry policy (15 minutes)

The precise shape of the NRF is yet to be determined, but both in purpose and in function it will be radically different from past examples of industry policy.

Its purpose is to help build “a strong and diverse” economy, which will see the creation of “sustainable high-value jobs”. That’s very different from policies directed at creating or sustaining employment in particular industry sectors. Some assistance through the NRF may go to firms classified as “manufacturing”, but as Geraldine’s guests stress, manufacturing is only one part of a long supply chain between raw materials and customers, and there are many high value-added and high-skill operations along that supply chain. In fact most manufacturing processes themselves these days involve very little employment.

If the NRF succeeds, that “strong and diverse” economy will look more like Germany’s economy of 2023, than Australia’s of 1953. We should once again be capable of doing complex things – in manufacturing and in other activities: we should not be hooked on ancient ways industries are classified as “manufacturing”, “service” and so on. We should be able to occupy, once again, a respectable ranking on Harvard’s Economic Complexity Index, where we are presently at position 91 (between Kenya and Namibia) out of 133 countries, having slid from position 55 in 1995.

And the NRF will function at arm’s length from government, helping firms in the early phase of investment in new technologies – one step along from R&D, and one step before going into operation. Such investments are project-oriented, which makes the NRF’s operations quite unlike the ongoing tariff and related assistance of earlier times.

The only connection with past policies is in its term “reconstruction”, reminiscent of the Curtin government’s Department of Post-War Reconstruction, headed by Nuggett Coombs. That was established to revitalize the Australian economy, badly knocked around by depression and war. In 2023 the task is to reconstruct an economy run down by decades of neglect, misguided by the “small government” dogma that saw economic structure being subordinated to the cosmetics of fiscal bookkeeping, and financial speculation privileged over value-adding investment.