Inflation, wages and profits

There are better ways to tackle inflation than jacking up interest rates

Ross Gittins notes a reversal in language around inflation. Those on the right used to talk about a wage-price spiral: greedy unionists would bludgeon hapless employers to make them pay higher wages, who would raise their prices, resulting in another push for higher wages ….

He observes that RBA Governor Philip Lowe has started to talk about a “price-wage-spiral”, but that’s about as far as Lowe has gone to admitting that our current round of inflation has started with corporations. In his article – Central banking: don’t mention business pricing power – Gittins notes that corporate profits have been rising in recent decades, and he dares to suggest that inadequate competition may be one of the reasons corporations have such power.

Crispin Hull is another who writes on corporations as a source of inflation. In his article Lowe’s weak weaponryHull reminds us that the RBA has only one big blunt instrument to contain inflation, but it isn’t very effective against corporate power. He notes that the Australian economy is “grossly uncompetitive”, and suggests that the government could give the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission more power to enforce competition. He also notes that the government has more and better-targeted mechanisms to reduce demand in the economy than the RBA has: scrapping the Stage 3 tax cuts is one obvious option.

Gittins asks “what’s the most glaring case of oligopolistic pricing power in the country?” The big four banks of course. Writing in the Sydney Morning Herald Clancy Yeates forecasts that the big four banks are tipped to rake in a record $33 billion profit this year. That’s a hard figure to grasp but it’s about $3 300 per household.

The Australia Institute has provided some hard numbers around influence of excess profits on inflation: Profit-price spiral: excess profits fuelling inflation and interest rates, not wages. According to its analysis, but for excess profits inflation would have easily fallen within the RBA’s 2 to 3 percent target band. “Excess corporate profits account for 69% of additional inflation beyond the RBA’s target. Rising unit labour costs account for just 18% of that inflation.”

The ABC’s David Taylor in his article The brutal truth of Australia's monetary policy: higher interest rates are coming, and it will hurt some more than others also remarks on corporations’ market power, with particular attention to the banks and the gap between the interest they charge borrowers and the interest they pay depositors. Peter Martin, writing in The Conversation, reveals that the gap between the RBA cash rate and the interest paid to savers has been widening over the last five years: See when Australia’s biggest banks stopped paying proper interest on your savings – and what you can do about it.

Tim Harcourt of Sydney’s University of Technology, writing in The Conversation, reminds us of what the Hawke government did 40 years ago, when it was confronted with a situation of established and apparent self-sustaining inflation. (That was a tougher situation than our present one, because inflation had set in for some time, while much of our present inflation is due to once-off price adjustments.) He asks, does Australia need another Prices and Incomes Accord?. While the government wouldn’t be able to replicate the Hawke Accord (it was relatively easy when half the workforce was unionized), it could forge “a grand bargain between unions, employer groups and other stakeholders”. He suggests that it would be “similar to Germany’s industrial relations model, which characterises employers and unions as ‘social partners’, working cooperatively with government”.

Who’s bearing pain from higher interest rates and who’s to blame – what the voters think

The latest Essential survey asked respondents whether people’s own experience of rising interest rates had been positive or negative. For a few (18 percent) rising rates were positive: presumably these would include people living debt-free enjoying the small rise in bank deposit rates. A third (33 percent) reported no impact from rising rates, while half (51 percent ) reported a negative impact.

Unsurprisingly two-thirds (67 percent) of those with a mortgage reported a negative impact, but one-third (31 percent) of homeowners without a mortgage also reported a negative impact. Also, as one might expect, the pain was concentrated among younger respondents.

These results suggest that the pain of rising interest rates is being borne much more widely than only among those who have recently bought into an overpriced property market.

The same survey also asked respondents what they believe to be the factors contributing to interest rate rises. In order the factors contributing “a lot” or “a fair amount” were:

- “Prices going up” (i.e. inflation) – 86 percent

- “Disruptions in supply chains triggered by the pandemic” – 76 percent;

- “The Reserve Bank of Australia over-reacting” – 72 percent;

- “The Federal Government” – 71 percent;

- “The war in Ukraine” – 60 percent;

- “Wages rising too quickly” – 38 percent.

It is difficult to know what people mean when they blame the federal government. Are they blaming the federal government elected last May or the federal government that blew much of the fiscal stimulus during the pandemic recession on programs that boosted corporate profits rather than spending on investments with enduring benefits? Do they believe that in the recovery phase from the pandemic fiscal policy should take on more of the burden of deflation, and if so should that be through higher taxes or even more constrained spending? Do they believe that the RBA is not truly independent, or that the government’s charter for the Bank is wrong? Or are they among those who hold to so-called Modern Monetary Theory who believe that the whole economic philosophy of high reliance on conventional monetary policy is wrong?

In assigning blame there are significant partisan differences. Coalition voters are much more likely than Labor voters to blame the government, and are inclined to believe that wages are rising too quickly.

Stop blaming the RBA Governor

It’s easy to forget that while Governor Lowe is the main public face and voice of the Reserve Bank, decisions on interest rates are made by the entire board. Karen Middleton, writing in the Saturday Paper – Lowe regard: RBA governor fights for his job – raises issues of board membership and governance more generally, which will be covered in the RBA Review due to be completed next month. There is a hint in Middleton’s article that Lowe feels that too much of the hard and politically thankless task of stabilizing the economy has been left to the RBA: the government could do more through fiscal measures to reduce public debt. That means further cuts to services or raising taxes.

Much of her article is about Lowe’s having addressed a private lunch hosted by senior executives in the financial sector. In itself that’s a minor issue, but its timing, between the Bank’s decision to raise rates and the release of its reasons, has raised questions about the closeness of its relationship with the banks.

A deeper criticism comes from the ABC’s Ian Verrender: Philip Lowe's long and gradual fall from grace after the many failures of the RBA. Contrary to the impression created by its title, it’s not about Lowe’s problems, so much as the general and long-term shortcomings of our central bank and the central banks in other countries. (The ABC seems to share with other media the problem of sub-editors who miss the point in their headlines.)

Verrender notes that when Lowe appeared last week before Parliamentary committees, he admitted that the RBA is not really equipped to deal with inflation arising from supply shocks. In view of the fact that at least 75 percent of our inflation results from external forces, that’s a strong admission.

While the RBA’s formal power lies in its capacity to set and influence key interest rates, it also has a significant influence in the market through its statements – “jawboning”. That’s why its strong hint that it would not move on interest rates until 2024 was so disastrously consequential.

In this context Verrender notes that rising interest rates are particularly painful for two reasons. One is that in Australia we have “insane” levels of household debt. (But for the ABC’s fear of being marked as a dangerously socialist outfit, he might have mentioned that this debt was fueled by the Coalition’s reckless policy of transferring the burden of debt from the government to households.) The other is the large proportion of loans written after 2020 that are vulnerable to rate rises.

Verrender’s strongest criticism of the Bank is its poor track record in economic forecasting. He presents data, which to its credit the Bank has published itself, showing that in 9 consecutive years the Bank’s forecasts have over-estimated the extent of wages growth. He asks if the Bank is now making a similar error with inflation.

Having found and presented this data, it’s unfortunate that Verrender hasn’t at least speculated on its meaning. Forecasting is subject to error, but a run of 9 errors in the same direction strongly suggests that a bias is at play. There is likely to be at least one seriously false assumption in the bank’s economic modelling. Verrender doesn’t single out the RBA: Treasury and private economists have been subject to biases in forecasting.

The hard-working and intelligent people who have built these models have impeccable credentials from university schools of economics, where they have absorbed what amounts to a globalized basic curriculum, at least in the English-speaking world. Do our economic models place too much faith, perhaps, in the power of the “invisible hand” to guide economic outcomes?

What’s worse – the inflationary spiral or the inequality spiral?

It seems to be an economic article of faith that inflation above some arbitrarily-decreed Goldilocks zone – presently 2 to 3 percent – is undesirable. But policymakers never explain why.

Maybe that’s because there is no clear explanation, because in a world where all prices, interest rates, exchange rates, wages, tax brackets, and government payments were perfectly indexed, and where people were well-informed and behaving rationally, inflation wouldn’t matter. To see why, imagine that you have just travelled to New Zealand, where you realize that $A1.00 buys $NZ1.10, and all prices in $NZ are roughly 10 percent higher. You soon adjust to that shift in place. Inflation, by this analogy, is a shift in time: a 2023 dollar is a different currency from a 2022 dollar. Children understand this perfectly when they bargain for pocket money, rejecting the parents’ argument that their older sibling was given $X when they were the same age.

The trouble is that the world isn’t so smooth and people aren’t so rational. People don’t understand the simple mathematics of inflation. Small investors who don’t understand the difference between nominal and real interest rates allow their savings to be slowly transferred to those who do understand the difference. Treasurer Peter Costello relied on such ignorance when he abolished indexation of capital gains taxation, effectively rewarding financial speculators and pushing up house prices while penalizing long-term patient investors. Ministers use inflation as a license to lie about changes in expenditure on programs – “we have increased spending on roads/defence/education/health by X percent” when inflation is more than X percent.

A left-wing conspiracy theorist could assert that fifty years of dumbing down high school mathematics was a deliberate move to keep the masses impoverished.

Most importantly, different groups in society have different power to adjust to inflation. Big corporations have no trouble in raising their prices, nor do most professionals in the private sector. By contrast those on the public payroll such as teachers and health care workers whose state government employers are starved of funds by the “small government” dogma, have little bargaining power: the most recent data on wages, the ABS Wage Price Index, confirms that wages of public sector workers have fallen more than wages of private sector workers. Unskilled workers and immigrants unfamiliar with our systems have little capacity to demand higher wages.

That’s why Reserve Bank Governor Philip Lowe and others correctly state that inflation widens inequality, but to explain why would mean having to refer to the power imbalances described above. That would be ungenteel, and would be seen as a swipe at government policy. So his statements have to take the existing power structures as given. For example, writing in The New Daily – RBA defence of interest-rate mallet highlights the truth about inequality – Alan Kohler notes that Lowe admits that the Reserve Bank’s moves against inflation have been tough, because, quoting Lowe, “It increases inequality and hurts people on low incomes the most”.

Kohler addresses another, more effective, way to address inequality – progressive income tax, reminding us that in the postwar years of strong growth our top marginal tax rate was 67 percent. That worked in two ways to produce an economy that was both fair and productive.

It was fair because, as he explains:

High tax rates drastically reduced the ability of the well-paid to accumulate wealth and also meant there was little point giving them big pay rises, since it would be mostly confiscated by the state. Executives simply didn’t ask for big pay rises for that reason, so more of a company’s salary pool flowed to lower-paid workers.

It contributed to productivity because high taxes provided public revenue to finance public goods that are necessary for the country’s prosperity. Illustrating that point Kohler writes:

Education and health care are far more important to economic growth than how much money the professional and business classes get to keep of what they make.

A decade of sluggish wage growth ends with a freefall

The ABS Wage Price Index, published on Wednesday, must surely have shocked those ideologues who still believe wage growth is feeding inflation.

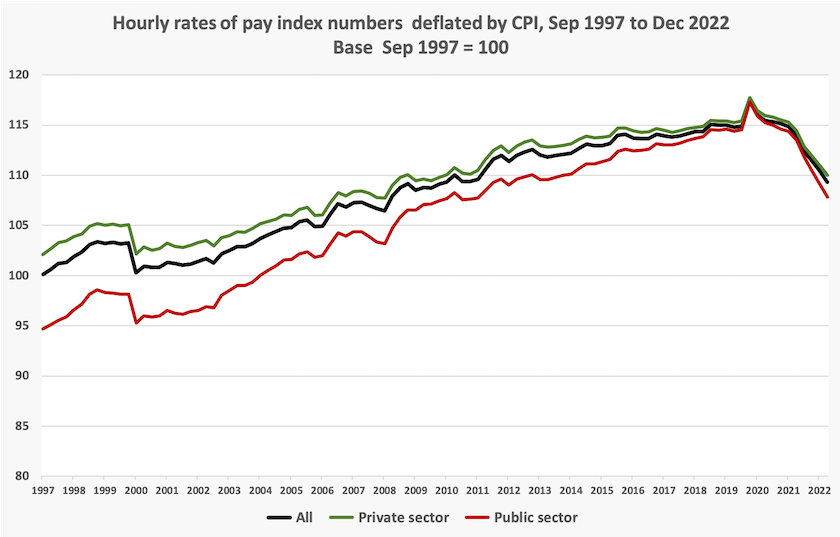

The graph below is a conversion of the published wage price index to CPI-adjusted terms. That means it presents the movements in wages from 1997, when the ABS series commenced.

If we were in wage-price spiral, as some believe, the CPI and the wage price indicator would be the same, and the lines would be running flat. But they’re not flat: real wages, temporarily boosted during the pandemic, have been falling sharply since mid-2020 – two and a half years. It takes time for falling real wages to register with people: they adjust temporarily by running down cash reserves or extending credit card debt.

That’s the short-term history. The medium-term history is also shown in the graph, which reveals that from around 2013 until 2018 real wages hardly rose, and then flatlined. Also public sector wage growth caught up with private sector wage growth. The Coalition can confidently claim that they managed to suppress wages during their term in office, but although that was their deliberate policy, they rarely boast about it.

It is informative to have a look at the ABS website, linked above, because it presents a graph showing the contributions to recent nominal wage increases related to methods of setting pay. Rises in nominal wages have been enjoyed mainly by those on individual agreements, while those on enterprise agreements and awards have done poorly. Award rises are seasonal, showing up only in the September quarters. It will be July before workers on awards can expect even a nominal pay rise.

Next week will see publication of the December quarter National Accounts. They are likely to reveal a further shift in the profit-to-wages ratio in GDP, to the benefit of profits, but the extraordinary profits of banks, supermarkets and Qantas, revealed so far in the current corporate reporting season, won’t show up until this quarter’s National Accounts are published in June.

The ABC’s Gareth Hutchens analyzes the wage data in political terms. Corporations and the government are claiming credit for the recent growth in nominal wages. But no government in a democracy, particularly a social-democrat government, can pretend to be powerless in a situation where wages are going backwards while corporate profits and executive salaries are soaring. Even if people don’t blame the government for getting us into this mess, they will expect the government to do something tangible to haul us out of it.

The harder problem for the government to face is the damage wrought by a decade of poor economic management, in which structural economic policy was neglected, and the public sector was emasculated by the impoverishing low-tax-small-government ideology, resulting in a collapse in labour productivity. There cannot be a sustainable rise in real wages until productivity improves, and that won’t happen until public and private investments in economic re-structuring take effect.