Politics

The Aston races

Alan Tudge’s resignation precipitates a by-election for the Aston electorate. It’s in Melbourne’s east, lying between the Eastlink tollway and the Dandenong ranges.

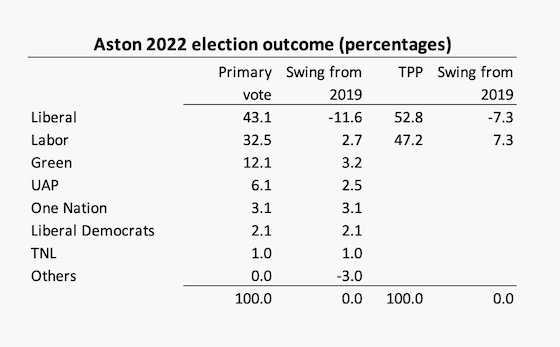

Since 1990 it has been held by the Liberal Party, with a generally improving TPP margin. The 2022 result, shown below, was a distinct break from this trend, however. It is now one of only three seats held by the Liberal Party in the Melbourne urban region, the others being Deakin and Menzies, both to the north of Aston.

Notably there was no independent in the 2022 election.

The ABS 2016 census data for Aston (on slightly different boundaries) reveals it to be close to the national average on most demographic indicators, including education attainment, age and income. The only minor differences are a significant proportion of first- and second-generation immigrants, particularly from China and India, and a high rate of home ownership, with and without mortgages.

The prevailing political wisdom, based on historical experience of by-elections, is that it should swing back to the Coalition after such a large swing against it. Carla Jaeger, writing in The Age, however, suggests it is ripe for the picking by Labor. Indicating a trend away from the Liberals is a run of opinion polls showing a continuing loss in their support following the 2022 election, and a miserable outcome in the Victorian election in November.

For those who want to go into detailed analysis and speculation, William Bowe’s Poll Bludger pulls together a wealth of data on the electorate, with links to journalists’ comments and predictions.

Both main parties can be expected to fight hard in this by-election. For Labor it’s a chance to increase their House of Representatives presence from 77 (a majority of 1 after appointment of a speaker) to 78, and for the Liberals it will be seen as a political test for Peter Dutton. So far most media commentators are considering it as a Liberal-Labor contest: journalists seem to be conditioned to thinking that way. It could turn out to be a much more interesting contest however if others, not just the usual suspects, enter the contest.

Another possible effect of Tudge’s resignation is that a pending by-election may tone down the Coalition’s negative comments on renewable energy and Dutton’s divisive approach to the Voice.

The Coalition’s been around 100 years – but it feels longer

Frank Bongiorno of the ANU and David Lee of the University of New South Wales, writing in The Conversation, note that last week saw the 100th birthday of the Liberal National Coalition. They date its birthday to February 1923, when First Viscount Bruce of Melbourne, leader of the Nationalist Party, reached an agreement with Earl Page, leader of the Country Party, rather than 1944 when Robert Menzies constructed the Liberal Party out of the ruins of the United Australia Party, which itself was constructed out of the ruins of the Nationalist Party.

Will it all fall apart again? Bongiorno and Lee write:

Since its inauguration in 1923, the Coalition has occasionally collapsed, but it has also usually resumed relatively quickly. It is possible, however, that the dramatic electoral realignments seen at the 2022 federal election have created more difficult, and continuing, problems of Coalition management for Dutton than those faced by previous leaders.

The birthday has obviously been a quiet occasion. No one in Canberra was aware of abnormal levels of carousing and joyous celebration.

Asylum seekers: there are still 12 000 without a future

With little fanfare the government has moved 19 000 asylum-seekers off temporary protection visas, giving them a pathway to permanent residency, access to government benefits, and eventual citizenship.

But there are 12 000 others – 11 000 in Australia and 1 000 in Nauru and Papua New Guinea – who have not benefited from the government’s decision. In a process reliant more on chance than on administrative logic, those 11 000 asylum-seekers in Australia have been on bridging visas rather than on temporary visas. The ABC’s 730 Report – Thousands of refugees could still be left in limbo following changes to temporary protection visas – covers the way this has come about.

To their credit there are independent MPs working to give the government the political latitude they need to act with decency towards these people, subject to so many years of wanton cruelty. To their discredit Coalition MPs are maliciously spreading the idea that the government has abandoned “Sovereign Borders” and has thrown down the welcome mat to people smugglers.

There is a risk that those who have been longing for the government to right the wrongs of the past will believe that we have at last abandoned the Rudd government’s brutal policy towards asylum-seekers, particularly if they believe the opposition’s claim that the government has gone soft on asylum-seekers. They may not realize that pressure still has to be maintained on the Albanese government in relation to those other 12 000.

There is also a risk that people will no longer donate to charities providing services to asylum-seekers and to advocacy organizations. These organizations, including the Asylum Seeker Resource Centre and the Asylum Seekers Centre, still need our (tax-deductible) donations.

Waning trust in government and the media

One of the main findings of the 2022 Edelman Trust barometer is a collapse of trust in democracies. Among the general population of democracies, trust as indicated by reported trust in “industry, government and the media”, has fallen in many of the democracies surveyed, while rising in some autocracies.

Among countries with a significant decline in trust between 2021 and 2022 are Germany, the Netherlands, US, Australia and South Korea. By contrast trust has risen significantly in China, the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia. The UK and Japan remain near the bottom of the list of 27 countries surveyed, and Russia still holds last position by a large margin.

Notably people in poor but strongly developing countries are likely to agree with the proposition that “my family and I will be better off in five years’ time”, while people in prosperous “developed” countries are likely to disagree with that statement. Western Europeans are particularly pessimistic.

Within countries there is a trust gap between those with high incomes and those with low incomes: if you’re well off you’re more likely to trust “industry, government and the media” than if you’re poor, and that trust gap has been widening over the last ten years. An inference from that finding is that it is probably becoming easier for populist movements peddling false information to spread disaffection among the poor and excluded.

Another large trust gap the researchers found was between US Democrats and Republicans, particularly when it came to trust in government.

Australia is among countries with low and falling trust in media. But is this necessarily a negative indicator? It’s notable, for example, that China shows the highest (and still rising) trust in media. With the Murdoch media so strong in Australia it would surely be worrying if our trust score were high.

The barometer notes that in countries surveyed there is reasonably high trust in central banks. This may be a little different in the 2023 barometer.

Notably there is high trust in central health authorities in most countries, but it is low in the US, Brazil and Russia – three countries that handled Covid-19 poorly – and it is very high in China where until recently there were harsh but highly effective Covid-19 controls.