Economics

The Reserve Bank vs Australia

Choice of words counts.

On Tuesday 7 February, when announcing its latest decision to lift interest rates, the Reserve Bank stated that it expected to go on raising interest rates in the coming months. On Friday 10 February, in its more comprehensive Statement on Monetary Policy, lest anyone had any doubt about the Bank’s resolve, it repeated the message, in almost the same words (annotations mine):

The Board expects that [not “will consider whether”] further increases [plural] in interest rates will be needed over the months ahead [suggestion that there will be no let-up] to ensure that inflation returns to target and that this period of high inflation is only temporary. In assessing how much [not “whether”] further interest rates need to increase, the Board will be paying close attention to developments in the global economy, trends in household spending and the outlook for inflation and the labour market. The Board remains resolute in its determination to return inflation to target and will do what is necessary to achieve that.

The Bank’s almost unqualified assuredness has spooked financial markets and raised an angry and bemused reaction, not only from mortgagees, but also from many independent economists. That assuredness has two aspects – that inflation, whatever its causes and duration, is an unmitigated evil, and that the Bank’s setting of interest rates will bring it back down.

On the ABC Breakfast program former RBA Governor Bernie Fraser guardedly criticizes the Bank for making such assured statements (9 minutes). He suggests it would have been wiser for the Bank to have adopted a “wait and see approach”, while its 9 interest rate rises to date work their way through the economy, and as other forces contribute to lowering inflation.

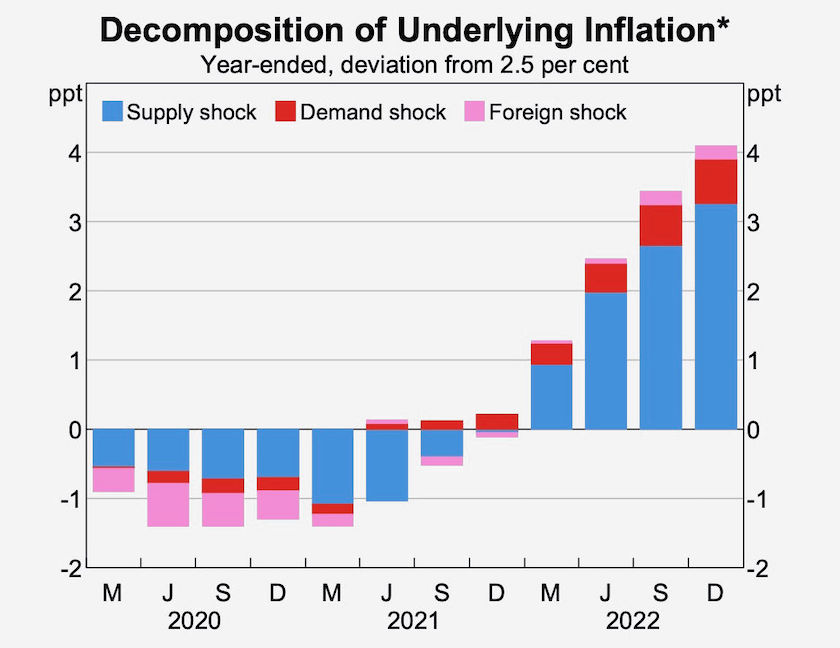

On the ABC’s website, in separate articles, Gareth Hutchens and David Taylor consider one of the Bank’s main pieces of analysis, which actually suggests that the inflation we’re experiencing will not respond to interest rate changes. While monetary policy can influence price rises originating from consumer demand, it has little effect on businesses’ decisions to put up prices, which is the main source of inflation.

They both refer to the graphic below, copied from the RBA Statement, showing that most inflationary divergence from the Bank’s 2.5 percent target zone is because of “demand shock”: that is, inflation resulting from firms’ decisions to raise prices, contributing to boosted profits.

Taylor quotes Jim Stanford from the Centre for Future Work:

There's no doubt that corporations have taken advantage of the supply chain problems and the desperation of consumers, to jack up prices far more than required to cover their own costs, and their record profits have made this inflation far worse.

Hutchens suggests that if it is necessary to reduce consumer demand as a way to reduce inflation, that can be achieved by measures to encourage saving rather than by the blunt instruments of monetary policy. That would put the mechanism back in the hands of government, rather than the Reserve Bank. It’s politically convenient for the government to let the Bank take the blame for interest rate rises as: they got us into this mess by holding interest rates down too long and by leading borrowers to think they would stay down. But Hutchens’ point is valid: there is plenty of fiscal room for the government to raise taxes to suppress consumption. For a prosperous country our taxes are very low, and have become more regressive over time.

As Bill Mitchell points out, the Bank is counting on households to cope with higher interest rates by running down their savings buffers if they have any: RBA loses all credibility with further interest rate increases. That’s an unwise policy in an economy already burdened with a very high level of household debt.

Alan Kohler, writing in The New Daily – The undemocratic independent Reserve Bank , draws attention to the supposed separation of the Reserve Bank from government. It’s politically convenient, particularly in the current environment, for the Treasurer to refer to that independence, but the government appoints the Bank’s board, and gives it a mandate. That mandate does not specifically mention inflation, but it does require the RBA to exercise its powers to contribute to “the maintenance of full employment in Australia”. Suppressing inflation is a means to economic ends, not an end in itself. Are Australian borrowers the victims of the common problem of displaced objectives in government policy?

The ABC’s Ian Verrender explains why he believes that the Reserve Bank is pushing us towards a recession we don’t need to have. It’s because of its obsession with the supposed trade-off between low unemployment and inflation – the Phillips Curve. Verrender suggests that this trade-off had some validity in earlier times, when Australian workers had more market power, but labour market regulation, immigration and technological change have all eroded the power of labour in Australia. (In the Bank’s Statement on Monetary Policy the tone of its writing suggests that it sees low unemployment as a problem, rather than as a desirable outcome. Presumably the Bank’s board members will be joyed by the January labour force figures, showing that the unemployment rate has risen from 3.5 percent to 3.7 percent.)

Greg Jericho, now with the Australia Institute, sees a glimmer of optimism in the Statement on Monetary Policy: “[It] predicts that wages by the middle of this year will be growing annually by 4.1 percent – up from the previous estimate of 3.9 percent”. But that still means there will be a fall in real (inflation-adjusted) wages over 2023 he writes: The destruction of real wages will take a long time to recover.

John Hewson, in his regular Saturday Paper contribution – The pain in the RBA’s campaign – suggests that over the long term monetary policy in Australia has been poorly managed. The RBA (or the government before its independence) has tended to hold expansionary monetary settings too long, and has had to respond with sharp over-reactions.

Don’t blame the RBA: blame the established macroeconomic model of monetary policy

There are hounds out after RBA Governor Lowe, ignoring the reality that the Bank’s decisions are made by the board and not by its governor, and that it has only the crude instruments of conventional monetary policy at its disposal. Ross Gittins writes that Lowe’s not the problem – the system is rotten. “Why does stabilising the economy have to be done in such a round-about and inequitable manner?”, he asks.

The wide issue is the general limitation of monetary policy, which, in simple terms, hangs on the ability of the amount of money in the economy, as governed by interest rates, to regulate the level of economic activity. Too little money –> unemployment, too much money –> inflation. Q.E.D.

That would be a workable model if all resources in the economy were fungible – if bricklayers could take up work as surgeons, if school teachers could become drivers of road trains, and if capital and labour could be easily interchanged. After all “full employment” in economists’ terms refers to utilization of both capital and labour, and assumes all resources to be interchangeable.

But the world isn’t like that simple macro model. Workers are specialized. Economies are regionalized. Institutional arrangements allow the incomes of some to rise while others have sticky nominal incomes. And the cost of money – the interest rate – isn’t the sole regulator of economic activity. Personal and business decisions whether to save or spend are based on many variables, most notably confidence.

One of our readers has reminded us that the staunchest critics of monetary policy as it is practised are those who embrace the ideas of Modern Monetary Theory. (The adjective “modern” is a misnomer in my view because MMT is rooted in quite conventional and robust economic principles). MMT focuses on the efficient allocation of real resources in all parts of the economy, dispensing with the idea that resources are fungible. If teachers are unemployed and are needed in the economy, the government can print more money to employ teachers. If road construction costs are inflating because of supply shortages, the government can withdraw expenditure on roads until the resources become available. The focus is on full employment and price stability in all parts of the economy, and the supply of money is to serve that end.

The same reader has drawn our attention to a discussion on inflation on Michael Hudson’s website – a discussion with Radhika Desai of the Geopolitical Economy Research Group at the University of Manitoba – titled What causes inflation? Desai describes the relationship between money supply and inflation, but not in the simplified way most economics textbooks describe it.

She argues that an excess of money in the economy – as has been the case in recent years in “developed” countries – pushes up asset prices, but that asset price inflation goes unnoticed by monetary authorities who consider only the prices of goods and services rather than prices of assets – equities and houses. An increase in apparent wealth as indicated by the equity and real-estate markets stimulates its own increase in money supply, contributing to commodity inflation. The main fault of monetary policy as practised in “developed” countries has been to push up asset prices, which in turn has contributed to goods and services inflation, while also contributing to widening disparities in wealth.

Like Hutchens and Taylor, Desai points out that much inflation is temporary and onceßoff, and that some other inflation is a result of opportunities for firms to raise prices because of market concentration and the privatization of government services. (In this category toll roads, private health insurance and private school fees come to mind.)

Housing – plenty of room to fall

There has been a great deal of news about falling house prices, but we should look at housing prices over a longer term than one or two years.

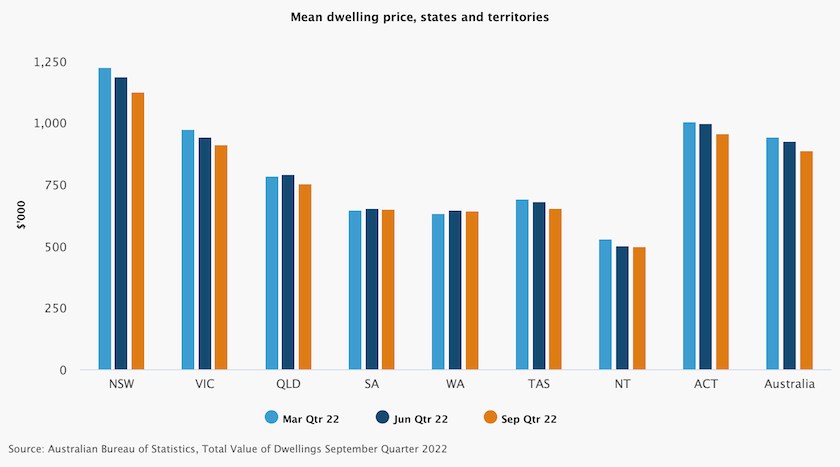

The figure below, taken from the ABS recently-established series on the total value of dwelling stock, shows price falls over 2022. It suggests that there may be some reversion to the mean: that is, where prices have been most elevated they are falling most quickly, towards prices in states where prices have never risen to the dizzy heights seen in Sydney, Melbourne and more recently Canberra.

More recent data, to January this year, is revealed in the Core Logic home value indices, which show a continued fall in house prices. According to Peter Hannam, writing in The Guardian, the boom in non-capital-city house prices is coming to an end.

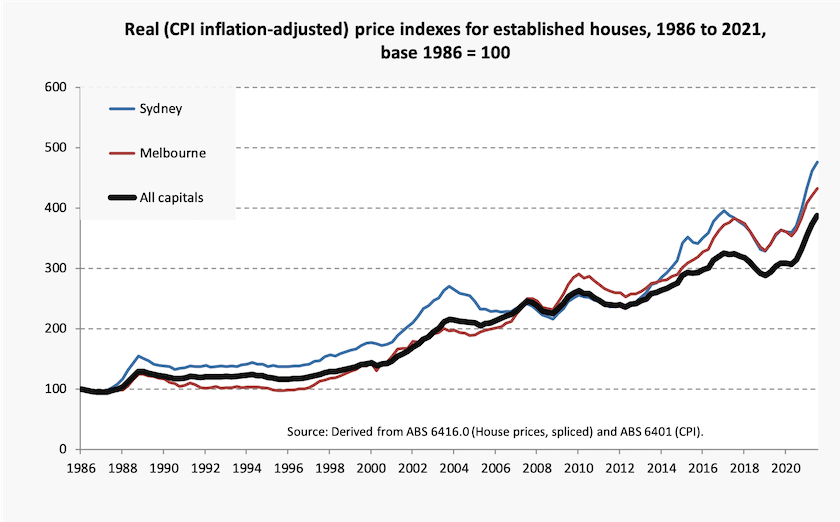

It’s worthwhile taking a longer-term view of house prices. The figure below shows established house prices (in capital cities) over the 35 years to December 2021, in real (inflation-adjusted) terms. Over that period house prices have risen fourfold – even more in Sydney and Melbourne.

The ABS series on which that graph is constructed has been discontinued – at a time when we really needed long-term information. The series had some methodological problems, in that there is no typical representative house, the price of which can be compared over 35 years. But when the media gets excited about falls in the order of 10 percent over a year it’s informative to consider these figures in a longer-term context. House prices are still higher than they were before the pandemic.

It will still be some time before house prices fall to reasonable levels. Immigration has resumed, there are skills shortages in the residential construction sector, and there are parties – real-estate agents, mortgage brokers, and the banks – who have an interest in keeping house prices high. (In this regard it’s notable that the Coalition, attending to the interests of these lobbies, is trying to block the government’s modest $500 million a year contribution to investment in affordable housing.)

Provided the banks do not foreclose on mortgagees (they have no incentive to do so), falling housing prices should cause little pain: the pain for mortgagees comes from rising interest rates. The real value of one’s house – its shelter, comfort, locational convenience – hardly changes year to year. There may be some “wealth effect” as people, irrationally, believe that a fall in the market value of their houses means they are worse off, and constrain their discretionary consumption – a case of economic irrationality achieving the Reserve Bank’s objective.

Falling prices and reduced turnover of houses have their strongest real effect on state government revenue: the New South Wales government is forecasting a $1.7 billion fall in stamp duty revenue this year. That’s another strong reason to abolish stamp duty on real-estate sales – an unnecessary burden on first-home buyers – and replace it with a land tax on all property owners.

Labour relations policy – flexibility without exploitation

One obvious, and often touted, solution to exploitation in the gig economy is to ban the gig economy outright, forcing every worker to be in regular employment in master-servant relationships, covered by awards.

The unions would love it, as would lawyers writing complex award provisions in fast food, trucking, and other industries that don’t have regular working patterns.

Not all gig workers would be enthused, however. Some like the flexibility of gig work, and prefer a contractual relationship to a master-servant relationship. Many want to provide their own tools of trade – a motorcycle, a semi-trailer prime mover, computing equipment and so on – rather than depending on corporate bureaucracy.

In a speech to the Chifley Research Centre, Employment and Workplace Relations Minister Tony Burke recognized that the gig economy and self-employment are suitable forms of work for many people. There has to a be better choice, however, than between workplaces with no minimum conditions and workplaces subject to the full constraints of master-servant relationships covered by detailed awards.

Burke says that the government is working with industries – food delivery, trucking, performing arts and others – to work out solutions for industries where gig work and self-employment are established. Solutions have to be industry-by-industry. Some firms with a poor attitude to their workers may disappear as they deal with the need to treat workers fairly, but Burke reports that the government is making good progress with other firms who are taking their places. There is no loss to Australia if a multinational food delivery firm, indifferent to the dangers faced by its drivers, pulls up its stakes, or if a delivery company that goes for the cheapest quote that can be provided only by a desperate owner-driver whose rig has worn brakes, goes broke. Enterprises operating ethically and responsibly in the market place need the protection of well-regulated markets.

In the same speech Burke referred to the government’s general priorities to lift minimum wages, to crack down on loopholes that some employers use to get around awards and agreements, and to close the gender gap. He was particularly critical of the over-use of labour-hire companies: they have a legitimate role in providing specialist skills and surge workforces, but not for providing a regularly-employed workforce.

On gender equality the government is pushing ahead with an amendment to the 2012 Workplace Gender Equality Act to require all companies with more than 100 employees to report on their gender pay gap. But writing in The Conversation Mark Humphrey-Jenner of the University of New South Wales warns that the way the government requires companies to report does not necessarily provide a clear account: it can hide a gap or indicate a gap where none exists. He suggests a simple mathematical fix to make reporting more accurate.

Consumer economics: dark patterns and carbon neutral patterns

Dark patterns

The consumer organization Choice is not known for spreading conspiracy theories. In fact they could be described as an institution dedicated to developing consumers’ scepticism in their market interactions.

So when consumer organizations like Choice warn about “dark patterns” – “business practices employing elements of digital choice architecture, in particular in online user interfaces, that subvert or impair consumer autonomy, decision-making, or choice” – their advice is worth heeding.

Dark patterns aren’t about invitations from a Nigerian executor of a deceased estate inviting you to send your bank account and passport details. Rather they’re about clever website design that makes it too easy for you to disclose personal information to commercial entities, or to buy stuff or add-on services that you don’t need.

The OECD has produced a report on dark commercial patterns, describing how they operate, providing examples, and suggesting regulatory policy responses. While the internet should widen consumer choice through making comparison shopping easier, dark patterns are designed to subtly constrain competition. The OECD report is yet another reminder that a well-functioning market may need the regulatory hand of government to keep it competitive – a basic principle of economics usually overlooked by the right-wing anti-regulation brigade.

For a quick take you can see a recording of a webinar in which for the first 22 minutes the report’s author, Australian Nicholas McSpedden-Brown, takes you through his work, followed by a session with Alan Kirkland of Choice Australia, Delia Rickard of the ACCC, and Erin Turner of the Consumer Policy Research Centre, where they discuss the application of the work to the Australian context.

False green patterns

Do we really know what it means when a company promotes its products as “carbon neutral”, or what the trademark “Climate Active” means?

If you are unsure, don’t worry. The Australia Institute reports that “while 85 percent of Australians have heard of the term carbon neutral only 33 percent of Australians know what it means”. That raises the possibility that use of the trademark “Climate Active” is misleading consumers who do not realize that such status can be achieved by using carbon credits rather than through a firm’s own decarbonising efforts, and that many carbon credit claims do not stand up to scrutiny.

The issue is outlined in a press release: Australian government breaching consumer law following Four Corners, which has a link to the Environmental Defenders Office paper taking up the matter with the ACCC as a possible case of false and misleading conduct under consumer law. The EDO paper documents examples of companies that have made doubtful claims about carbon neutrality.

The Four Corners program referred to by the Australia Institute is the 13 February episode Carbon colonialism: can carbon credits really save the planet?, about practices in forests in Papua New Guinea that are claimed to be carbon sinks.