Health policy

Resuscitating Medicare

Our primary health care system is showing its age. Its basic architecture is little changed from the 1970s, when the Whitlam government, in a political struggle against extraordinary opposition, established a universal taxpayer-funded primary health care system, based on fee-for-service remuneration. That was to become established as Medicare [1] after further struggles between 1975 and 1983 when the Coalition government and the financial sector (private health insurers) conspired to undermine it.

In the 1970s Australian life expectancy was around 72 years; it is now around 84 years. Our main health care concerns were about episodic illnesses and accidents; they are now about enduring chronic conditions. The typical primary health care provider was a sole-practice GP (almost all male); now there are larger practices often under the umbrella of large corporations. Nurses had only basic-qualifications and engaged in supplementary health-care tasks; now they are highly qualified but under-utilized. Computers were big machines used only by big companies; now information technology is integral to all enterprises, but the health care sector is not making the best use of IT.

More recently a shortage of GPs has emerged, corresponding with (but not solely caused by) lower real remuneration of GPs. The Covid-19 pandemic has exposed some of the weak points in our health care arrangements; fortunately our governments implemented solutions for problems such as urgent prescriptions, but these were more in the nature of work-arounds than permanent solutions.

The Strengthening Medicare Taskforce, a panel of experts and stakeholders established by the newly-elected Albanese government last July, has produced its report in a remarkably concise 12-page document. It calls for “blended funding” models of care – a break from 100 percent reliance on fee-for-service, integration of the skills of GPs, nurses and other professionals to deliver services, and modernization of IT systems.

Reflecting its tight fiscal policy the government has budgeted only $750 million for primary health care reform, and that is to be spread over several years. To put that into perspective, our total annual expenditure on primary care in 2018-19 was $67 billion, of which $41 billion was from Commonwealth and state governments. But it’s a start, and there could be gains from better utilization of our existing resources.

In a Conversation article titled Medicare reform is off to a promising start, now comes the hard part, Peter Breadon and Lachlan Fox of the Grattan Institute write:

While there have been many calls to throw more money into the existing system, the taskforce recommends a trickier, but necessary, course toward the structural, long-term reform general practice needs.

Those who have been around for some time may feel a little déjà vu. The Whitlam government, anticipating future health care needs, set out to establish community health centres, involving most of the features recommended by the Strengthening Medicare taskforce. The program languished, partly because of concerted opposition from state Coalition governments and later Commonwealth governments, partly because in some states the medical lobby groups refused to staff them, and partly because many of the centres were established in poorer urban regions meaning that they didn’t win support from the middle class.

Labor rhetoric is about universalism, but under budgetary pressure it often tends to see health care as a program as distributive welfare, with means tests and special programs for those who are struggling. When that happens programs become bogged in the bureaucracy around eligibility, and programs for the poor, lacking support from the middle class and others with political voice, become run down.

It is also notable that the government’s priority relates only to primary care. It is well aware that public hospitals are over-burdened, confirmed in the regular Report on Government Services updated last week. For many years those advocating reform of our health care arrangements have called for more integration between primary care and hospital care, but the Albanese government is not pursuing that path for now. Possibly they realize, drawing on the experience of the Rudd government, that the private health insurers will do all they can to scuttle any economically responsible reform to the way hospitals are funded.

GP rebates

In 2013 the Gillard Government, in a decision driven more by fiscal considerations than by sound economics, froze Medicare payments for GPs. The fee for the most common service – item 23, the short GP consultation – was frozen at $36.30. As if to confirm that the Coalition can always outdo Labor for economic stupidity, the Abbott government allowed it to rise to $37.05, and later the Coalition froze it at that level for another three years.

In a 2016 article the “Royal” Australian College of General Practitioners described the specific government decisions around indexation. Suspension of indexation applied to more services than those provided by GPs, but GPs were the most affected. Partial indexation was re-instated in 2017, but it has generally been below the rise in wages or the CPI. GPs have maintained a campaign to have full indexation restored.

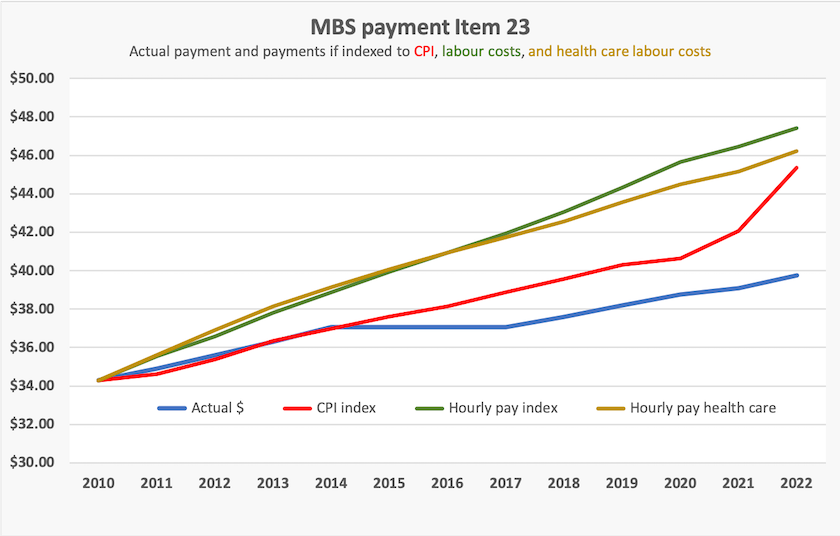

The graph below shows how the Item 23 payment would have moved under different indexation rates – CPI, economy-wide labour costs, and labour costs in the health and human services sector.

Had indexation been sustained, the Item 23 payment, now just on $40, would be between $45 and $48, depending on which index is used. Note that pay in the health and human care sector generally has risen more slowly than pay in the economy as a whole.

1. The term “Medicare” is often used to refer to all government-funded health care, including public hospitals, where the principle of universality is the same as for primary care, but funding is on a DRG basis rather than an individual fee-for-service basi. ↩

The outback – beautiful but unhealthy

Wilcannia Hospital – one of the better-served regions

Women living in the most remote parts of Australia are dying 19 years younger than women living in our big cities.

That’s one of the headline-grabbing findings of a report Best for the bush: rural and remote health base line 2022, prepared by the “Royal” Flying Doctor Service.[2]

Most, but not all, of that difference reflects the difference in health outcomes between First Nations and other Australians. But it is also about people’s lifestyle in the outback, where health risk factors are more marked than in urban Australia, and the absence of services.

Indigenous Australians have worse health outcomes, a higher incidence of health risk factors, and poorer health care services, than other Australians. Similarly non-indigenous Australians living in the outback also have worse health outcomes, a higher incidence of health risk factors, and poorer health care services, than urban Australians. Indigenous Australians living in the outback have a double disadvantage.

Some of the disadvantage is revealed in leading causes of death. Coronary heart disease is the major killer for all Australians, but in “very remote” Australia diabetes and suicide are two of the five leading causes of death. They don’t show up in any other urban or rural regions’ five leading causes of death.

The report is rich in statistics of people’s health conditions, their risk factors, and their access to health services, with comparative data for different regional classifications. It also provides a great deal of data on the Flying Doctor Service – which has a particularly challenging caseload.

The report calls for better access to primary care. It realistically accepts that those living in remote regions can never expect the same level of services as those in cities and large country towns, but it does call on policymakers to establish a nationally-agreed definition of “reasonable access”.

2. Its name is somewhat misleading. It is actually a long-established and highly-respected Australian service, with no connection with British royalty other than a historical name. ↩

Covid-19

In last week’s roundup I presented the data showing that 14 451 Australians died of or with Covid in 2022, and that Covid’s high death rate has continued into 2023. Public health campaigns from our governments have abated, but Covid is still raging.

Under-vaccinated older people are now filling Covid wards. Australia had a good uptake of first and second shot vaccination, but that was many months ago. We are now lagging seriously in getting booster shots and our immunity from vaccination or infection is waning.

The official advice from the Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation (ATAGI), with only minor qualifications, is that everyone aged 8 or over, who has not had Covid or vaccination in the last 6 months should get a booster dose, regardless of the number of prior doses they have had – 0, 1, 2, 3 or 4. ATAGI uses the word “consider” for people under 65, and “recommended” for older Australians. Sathana Dushyanthen of the University of Melbourne, writing in The Conversation, offers the same advice, and explains the reasons behind her advice: Haven’t had COVID or a vaccine dose in the past six months? Consider getting a booster. Norman Swan on the ABC’s 730 Report has the same advice in slightly stronger terms. He doesn’t use the word consider: he says we should have a booster, and spells out the risks of long-Covid. (5 minutes)

As illustrated in last week’s roundup, the waves of Covid-19 are becoming less peaky, but Swan points out that an extended period of low transmission is just as deadly as a short period of high transmission.

We should remember that vaccination is not just about protecting ourselves. It’s also protecting the community, and the better the community is protected the better is each individual protected.