Economic policy

The Reserve Bank works in mysterious ways, its wonders to perform

Two quotes from the RBA statement accompanying its lift in interest rates to 3.25 per cent:

Inflation is expected to decline this year due to both global factors and slower growth in domestic demand. The central forecast is for CPI inflation to decline to 4¾ per cent this year and to around 3 per cent by mid-2025.

and

The Board expects that further increases in interest rates will be needed over the months ahead to ensure that inflation returns to target and that this period of high inflation is only temporary.

That is, they expect inflation to fall, but they will go on lifting interest rates anyway, even though they recognize that “monetary policy operates with a lag”.

The expectation of “further increases” (plural) has spooked financial markets, because many economists believed the bank was coming to the end of its anti-inflation crusade: surely it would sit back and assess how its rate rises are taking effect, and monitor the movements of items subject to once-off price increases. But it has signaled its intention to barge ahead, without acknowledging the risk that it may be over-reacting.

Peter Martin, writing in The Conversation (just before the RBA decision) reports on the views of a panel of 29 economists about the inflationary and general economic outlook. He does not pull it all together in one forecast or recommendation, but the inference is that the RBA should be cautious. Economists expect there to be a sharp fall in inflation; wages growth is constrained by our enterprise-bargaining system and by rising immigration; many mortgagees are already doing it hard; house prices are falling; and the world economy, particularly China’s economy, is sluggish. On their own these indicators would suggest that the economy is deflating.

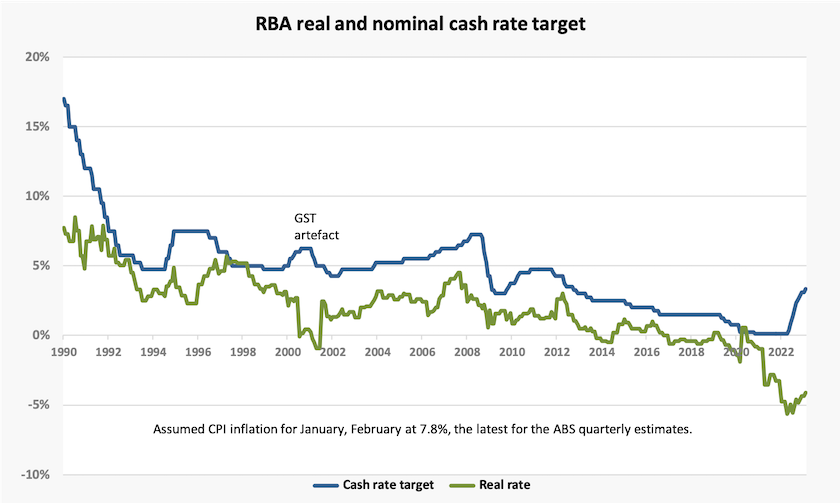

The graph below shows RBA cash rate and real (inflation-adjusted) interest rates. Real rates have been negative most of the time for the last six years, and are now clawing back towards positive territory after bottoming out in April last year. Strictly, the real interest rate relates to expected inflation, and as Peter Martin points out, economists expect inflation to fall. If inflation were to come back to 3.25 percent or lower, as some economists expect, the real rate would be zero, as it was for a long period before the pandemic.

Another Conversation contribution from Peter Martin after the RBA decision asks “why is the Reserve Bank determined to whack inflation further, rather than watch it slowly die?”

More on Treasurer Chalmers’ economics essay – it’s just old-fashioned orthodox economics

In last week’s roundup I provided a link and a short review of Chalmers’ Monthly essay Capitalism after the crises, commenting that it is based on orthodox economics. It acknowledges both the power and limits of markets, and recognizes that there are market failures requiring government regulation or public provision. That’s the mainstream theory covered in economic textbooks, and that Miriam Lyons and I explained in our book Governomics: can we afford small government?

Hearing the squeals of horror from some quarters, including former Treasurer Peter Costello, one would believe that Chalmers has issued a manifesto for the nationalization of Australian industry, which will be placed under the direction of the Labor Politburo. Chalmers was shocked by such a strident reaction to a work of textbook economic orthodoxy.

On Saturday Extra last week Geraldine Doogue interviewed two people about the essay – business executive Diane Smith Gander of the financial technology firm Zip Co, and John Quiggin of the University of Queensland: Reshaping democracy: revolutionary or regressive? (20 minutes). They both had minor criticisms of the essay, suggesting that Chalmers should have provided some examples of policy initiatives that may emerge from these principles. But they agreed with its general principles: in fact Quiggin was critical of Chalmers’ enthusiasm for public-private partnerships, arguing that it is generally better for the government to take over complete control than to rely on the messy compromise of private-public arrangements. Perhaps Chalmers places too much faith in markets

Early childhood education

In line with its election promise, the government plans to make a significant investment in early childhood education and care. On Thursday Treasurer Chalmers sent a broad-ranging reference on ECEC to the Productivity Commission. Details are on the Productivity Commission site, with early notice that initial submissions will be due in April.