Covid-19

No, it hasn’t gone away

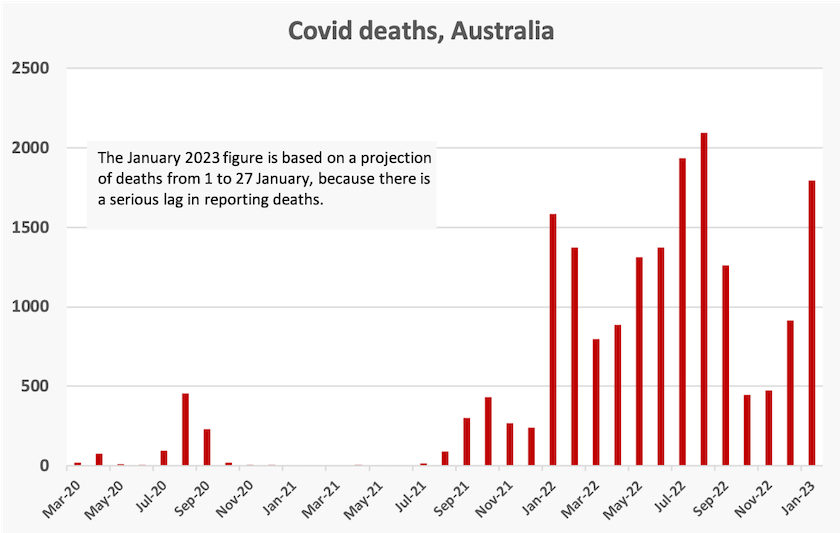

If one wanders into any mall, airport terminal, or other crowded indoor space, hardly a mask is to be seen. So it’s hard to believe that Covid-19 deaths have been rising over the last three months, and that January 2023 had the third highest number of deaths since the pandemic broke out three years ago.

Deaths are heavily concentrated among older people. The New South Wales regular surveillance report for the week ending 21 January shows that of 124 deaths in that week, 90 (73 percent), were of people aged 80 or older.

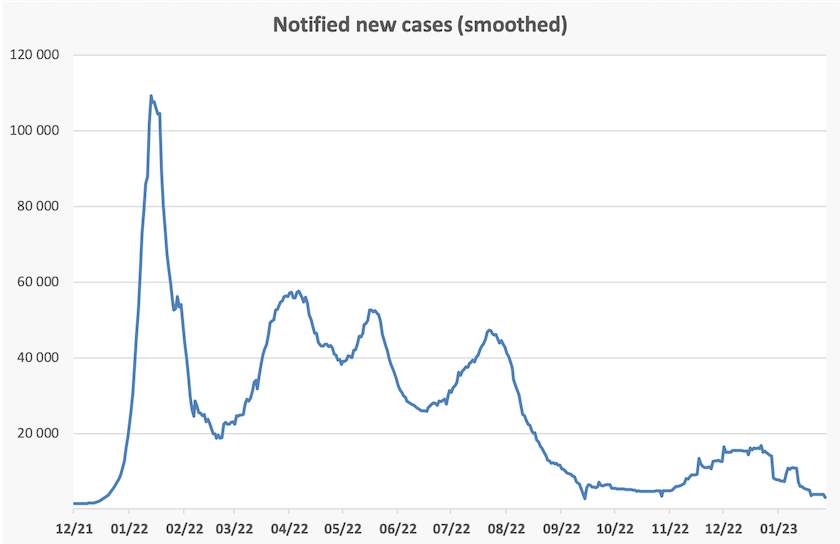

Deaths occur with some lag – generally around three weeks after diagnosis. Notified cases have been falling in January, suggesting there may be soon be a reduction in deaths.

Data from the Commonwealth confirms that the number of people being admitted to hospital with Covid-19, the number of people in hospital, and the number of people in ICU, are all falling. There is similar data, with more meaningful state disaggregation, in The Guardian’s Covid-19 data tracker.

All of this data should be treated with caution, however. Even as deaths have risen over the last two years, the quality of data provided by Australian governments has deteriorated. Writing in The Saturday Paper – Unmasking Covid secrecy – Martin McKenzie-Murray suggests that the Commonwealth government is deliberately secretive around Covid-19. It’s not clear why the public is not being trusted with available information: possibly it’s because of a fear of misinterpretation, or selective use of data by those spreading misinformation abut vaccines.

One crucial piece of data that’s missing, or available only after a very long lag, is the extent to which Covid-19 is displacing other viruses.

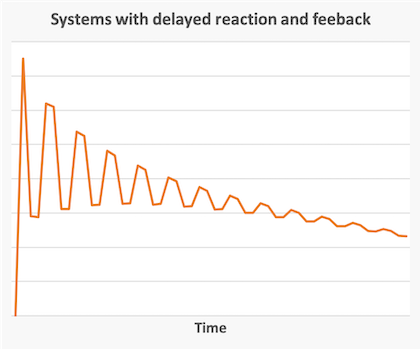

Australian hospitals report on the number of Covid-associated deaths, but that doesn’t mean Covid has been the cause of death, and there are lags in reporting deaths. Cases numbers are particularly dodgy, because they rely on people reporting to authorities, which means that asymptomatic cases and false negative tests are under-reported, and there are lessening requirements for cases to be reported. All of these issues considered, case numbers are likely to be subject to a more significant bias of under-reporting as time passes. Nevertheless they do reveal trends, and system analysts would recognize that cases are following a fairly standard pattern, found in mathematical models of high-gain systems subject to delayed reaction (slow feedback). A simple representation of such a system response is shown alongside.

To explain such system behavior in non-mathematical terms, as cases or deaths rise people adjust their behavior, becoming more cautious. That caution shows up a few weeks later as fewer cases, resulting in people becoming less cautious, which means the cycle starts again. But each cycle tends to be less severe than the preceding one as hybrid immunity improves and possibly as the virus become less virulent (but no less contagious). If Covid-19 is following such a pattern, we can expect more waves of infections and deaths, each wave being a little less pronounced, but the virus will never go away.

That is probably what the WHO means in its statement of January 30, where it grapples with the decision whether to continue calling Covid-19 “a public health emergency of international concern”. It says:

The Committee acknowledged that the COVID-19 pandemic may be approaching an inflexion point. Achieving higher levels of population immunity globally, either through infection and/or vaccination, may limit the impact of SARS-CoV-2 on morbidity and mortality, but there is little doubt that this virus will remain a permanently established pathogen in humans and animals for the foreseeable future. As such, long-term public health action is critically needed. While eliminating this virus from human and animal reservoirs is highly unlikely, mitigation of its devastating impact on morbidity and mortality is achievable and should continue to be a prioritized goal.

For now, Covid-19 remains “a public health emergency of international concern”, but the WHO expects to drop that classification in the near future, as member states and international organizations develop and implement “sustainable, systematic, long-term prevention, surveillance, and control action plans”. That’s a strong hint about the need for attention to ventilation and simple measures like mask-wearing, to suppress the rate of reproduction of the virus.

The pattern described above is one which would be familiar to public health experts, and it is a fair approximation of the way viruses have behaved in the past. But writing in The Saturday Paper – What we got wrong about Covid-19 – Peter Doherty reminds us that Covid-19 has characteristics that distinguish it from past viruses, particularly its extraordinary capacity to mutate. He writes that “there is no obvious evolutionary reason why more severe strains could not emerge”. In addition this virus carries the debilitating effects of long-Covid for many who contract it, but long-Covid generally does not show up in hospitalization or death statistics. Doherty goes on to provide advice for how our government can deal with the next viral pandemic, or a serious variant of Covid-19.

Also writing in The Saturday Paper, Karen Middleton reports on generally similar warnings from Jane Halton: Halton report warns of repeating Morrison errors. Both Doherty and Halton suggest that in future governments may have to rely more on antiviral medications to be administered once people have contracted Covid-19 or similar viruses. That appears to be simple enough, but it would require a more responsive health care system without delays in obtaining medications, and if it is to be affordable it would require a more reasonable pricing system. Our pharmaceutical pricing system does not allow the price the government pays for pharmaceuticals to be reduced as volumes expand and drug companies enjoy the benefits of scale economies. The companies’ costs to develop new pharmaceuticals are very high, while the manufacturing costs for most pharmaceuticals are very low. Therefore the companies stand to make extremely high and unjustifiable profits when there is a significant expansion in the market.