Australia’s energy transition

How are we tracking?

Dylan McConnell of the University of New South Wales warns that we are adding renewable energy at less than half the pace required to replace retiring coal-fired generation, to keep the power supply stable, and to meet our 2030 climate target.

At the same time Renew Economy has a series of upbeat stories about renewable energy. There is to be a world first solar methanol production plant at Port Augusta, as well as three new green hydrogen projects in New South Wales and Queensland. The New South Wales government has shortlisted 16 projects comprising more than 4.3 GW of renewable energy. The ambitious Sun Cable project to supply electricity, to be generated from the world’s biggest solar farm in the Northern Territory, to Singapore through a DC line is still alive: the administrators are in the market seeking finance.

Bruce Mountain, writing in The Conversation, describes the disagreement between Sun Cable investors as a “setback”, but the idea of exporting renewable energy is realistic and is commercially feasible. Energy and Climate Minister Chris Bowen seems to be confident that the project will proceed.

There are more serious setbacks, such as problems besetting Snowy 2.0 which has seen huge cost blowouts. It will go ahead – there is too much sunk cost to see it abandoned – but it may not be built in time to prevent an energy shortfall.

There is no shortage of renewable resources in Australia, but as a group of ANU researchers point out in The Conversation, (and as described in AEMO’s Integrated System Plan), the most suitable sites for wind and solar need to be connected to transmission lines. Connecting those sites is addressed in the government’s Rewiring the Nation plan, and a large venture involving a commitment of $4.7 billion from the Commonwealth, and $3.1 billion from the New South Wales government to build transmission lines was announced on December 21.

Our energy transition is not proceeding on a smooth path: it would be naïve to believe that it could. There are setbacks, but there are also previously unforeseen opportunities emerging. As an analogy we can look at the way information technology has developed in ways that have always taken us by surprise.

Carbon offsets – do they do anything useful?

They will go on growing without carbon credits

Our 2030 and 2050 commitments to reducing emissions are heavily reliant on the use of carbon offsets. Almost immediately on being elected (on July 1) the government commissioned a review of carbon offsets as they have been used in Australia, noting that the integrity of the scheme had been called into question. That review was presented in January, reporting that the scheme was “fundamentally well-designed when introduced”. Its main concerns with the scheme relate to governance and administration, but the recommendations on methods of assessing the contribution of credits to absorbing carbon are more about tweaking the measures than making fundamental changes.

Andrew Macintosh and Don Butler of the ANU are highly critical of the report: Carbon credit scheme review falls short – and problems will continue to fester – published in Renew Economy and The Conversation. They draw attention to their earlier analysis that found more than 70 percent of credits issued for avoiding deforestation, regenerating native forests and combusting methane from landfills, “do not represent genuine emissions abatement”. They also note that there is a paucity of evidence supporting the report’s conclusions.

In spite of our experience of flood and fire, our knowledge of climate change is wanting

The media has reported that in comparison with other OECD countries our attitude to climate change is poor. In comparison with other high-income countries our knowledge of the mechanisms and effects of climate change is lacking, and we seem to be less willing to take action to reduce the effects of climate change.

The full paper can be downloaded from the OECD – see the PDF symbol on the summary website. Knowledge of climate change is closely related to education, and to people’s “economic leaning”. The more one is to the “right”, the poorer is one’s knowledge. On all three dimensions surveyed -- knowledge, willingness to take action, and support for climate change policies – Australia shows up poorly in relation to other high-income OECD countries. (Tables of cross-country data are on Pages 7, 16, 20 and 21.)

Electric vehicles – the market needs a nudge

The Productivity Commission is less than enthusiastic about policies that may subsidize people to buy electric vehicles. In its submission to the National Electric Vehicle Consultation it asserts that “EVs are likely to be mainstreamed from 2035, attempts to force the transition before that time should be avoided”. Subsidizing EVs, it says, is an expensive way to achieve emissions abatement. It is similarly unenthusiastic about government subsidies to provide charging points. It gives mild support to supply-side measures, particularly an improvement in Australian fuel efficiency standards. But it also warns that the uptake of EVs will require a more efficient road pricing system than our present de facto reliance on fuel excise. That would remove EVs’ present advantage over other vehicles.

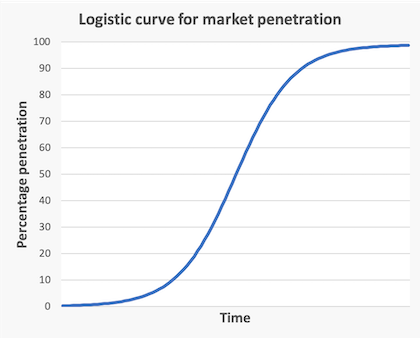

The Commission’s short paper would probably get an A grade as a first-year economics assignment. But it ignores the ways markets dependent on networks develop in a logistic function – that is with a very slow uptake until a critical penetration is reached, when the market takes off. Few people will buy EVs until there are enough charging stations; there won’t be enough charging stations until enough people buy EVs; and so on. In such situations there is a case for a subsidy to get the market going. The forgone revenue can be clawed back once the market reaches saturation.

Phil Laird of the University of Wollongong notes that our transport sector performs poorly on fuel efficiency in comparison with other countries. In a Conversation article – Why electric vehicles won’t be enough to rein in transport emissions any time soon – he argues that we will get our best return in terms of reducing emissions by improving fuel efficiency. His point is similar to that made by the Productivity Commission, but he tends to see a world with fewer cars as a desirable end in itself.

Some practical advice on EVs for long trips is in Geraldine Doogue’s Saturday Extra, where she interviews Tom Gan, an EV YouTuber, and Ross de Rango of the Electric Vehicle Council, on charging for EV road trips. Tom Gan describes a trip from Sydney to Melbourne and back in an EV. It wasn’t a fast trip – five stops on the downward journey, four on the return journey. (That may still be faster than anything airlines have to offer when one considers their reliability.) There can be delays waiting in line for others to charge their vehicles: Gan and Doogue discuss the emerging etiquette around charging stations, particularly in view of the time taken to get the last few kWh into a battery.

De Rango wants to see exporters allocate more EVs to the Australian market, and is keen to see improvements in fuel efficiency standards to stimulate the market. He expects that it will soon be possible to make Gan’s trip with fewer and shorter stops as fast charging stations are rolled out. (Tesla already has its high-quality proprietary network.) But for most of our vehicle use we won’t need to go to a charging station, because our EVs will be plugged in at home.

Tom Gan has heaps of EV stories and practical advice on his site.

The war against renewable energy

Deutsche Welle has a neat 12-minute YouTube video debunking some of the superficially credible arguments against renewable energy. The video deals with claims that the carbon footprint of making solar and wind systems more than offsets their emission reductions, that windmills are uncompetitive sources of electricity, that solar and wind are unreliable because the sun doesn’t shine all the time and the wind doesn’t blow all the time (the Coalition’s mantra), that serious network shutdowns have resulted from failures in renewables, and that windmills kill birds.

The substance of the video is about the way such destructive misinformation spreads, and how it is seeded in the first place. It spreads organically, often by anxious people, lacking reliable information and a capacity to assess claims skeptically, who seek more and more content that confirms their suspicions. Misinformation is often spread by outfits bearing impressive names, and with articulate presenters, and their claims may hold a grain or two of truth. The people at this stage of the misinformation supply chain are not the stereotyped right-wing loudmouth cranks.

The original sources of this misinformation and the sources of funding for those slick websites are harder to find, but there is no doubt that the fossil fuel industry benefits from this misinformation – “a trillion dollar industry clinging on to a business model”, with its grip supported by people’s doubt and fear of change.