Australia’ Constitution

Dutton’s deceit and the Greens’ naivety combine to oppose the Voice referendum

The referendum on the Voice is about a simple change to our Constitution.

The change, as presently proposed, involves three sentences, describing the Voice’s limited function and asserting Parliament’s sovereignty:

- There shall be a body, to be called the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice.

- The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice may make representations to Parliament and the Executive Government on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

- The Parliament shall, subject to this Constitution, have power to make laws with respect to the composition, functions, powers and procedures of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice.

That’s it, explained by the government on a refreshingly brief and informative website.

The reasoning behind these three sentences is expounded by constitutional expert Anne Twomey in a Conversation article An Indigenous Voice to Parliament will not give ‘special rights’ or create a veto. The constitutional question has to be agreed by Parliament, but it is unlikely to differ in any material sense from those three questions.

But as John Hewson explains in his regular column in the Saturday Paper, Dutton is out to wreck it:

Opposition Leader Peter Dutton is trying to complicate the issue, with his most recent stunt being the writing of an open letter to the prime minister seeking “more detail”. We all know the game here: create enough doubt and uncertainty to give the “No” case its best chance of success. Namely by running the line, “If you don’t understand it, don’t vote for it.”

The “open” letter was released only to selective media. It was not even sent to the prime minister, and is accessible only on Dutton’s Twitter account and on a special site provided by The Australian.

The “open” letter and these questions are not about the referendum.

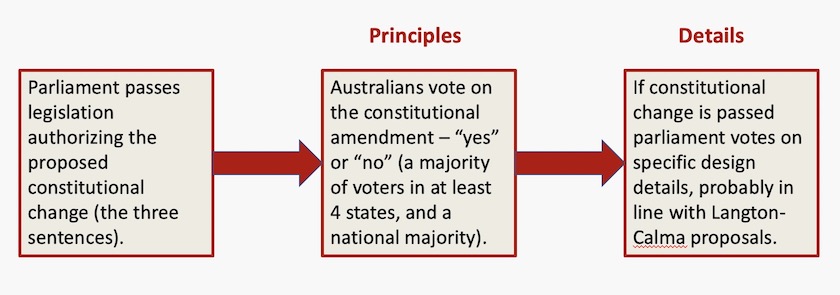

Rather they’re about the specific legislation the government would put to Parliament once the constitutional amendment has been made. The referendum is a prior and completely separate process.

Attorney-general Dreyfus makes that distinction quite clear in an 8-minute interview on the ABC’s 730 program, where he explains the steps in establishing a Voice. Constitutional expert Anne Twomey has said the details should not be released. Doing so would go against the point of the referendum. “If you start putting out a detail with the bill, et cetera, people will think that that's what they’re voting on in the referendum” she says.

Most of Dutton’s 15 questions are legitimate in the context of a bill to enact the Constitutional change in specific legislation, but we’re nowhere near that stage yet. That comes after the constitutional change on which we will be voting.

The diagram below shows the separate steps.

Perhaps the clearest explanation of the process is a 17-minute interview with Noel Pearson on ABC Breakfast, where he describes the demand for detail as a diversion. Pearson carefully explains the difference between the Constitutional amendment and legislation, dispelling any notion that some specific and immutable model is to be enshrined in the Constitution. He responds to an interview on the same morning with Liberal Shadow Attorney General Julian Lester, who ducks and weaves around Patricia Karvelas’s questions, leaving the impression that he is at one with Dutton in trying create enough uncertainty to sink the referendum. On that program Lester is followed by the ABC’s regular commentator Michelle Grattan, who does nothing to clarify the situation.

While experienced and non-partisan journalists like Karvelas understand the process (it’s not all that difficult) most comments on the media, including on the ABC for the most part, fail to distinguish between the referendum and legislation. Rather they jump straight into details of the legislation the government is to present if the referendum succeeds. That legislation is likely to be heavily influenced by the work of Marcia Langton and Tom Calma who, after extensive consultation, wrote the Indigenous Voice Co-design Process – Final Report to the Australian Government in July 2021.

But that’s not what we will be voting for in the referendum.

In his Saturday Paper article —Inside Labor’s Voice Strategy — Royce Kurmelovs emphasizes that Labor has not adopted the Langton-Calma report’s recommendations, and has tried to keep the debate focused on principles. Unfortunately supporters of the Voice seem to be getting sucked into talking about details, inadvertently helping to spread Dutton’s false impression that the referendum is about a specific and detailed model.

The Greens seem to be on a different but also destructive tack, suggesting that they won’t support the Voice unless there is progress on treaty negotiations. This is depressingly similar to the Greens’ strategy in 2009, when they refused to support the Rudd government’s Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme, delaying action on climate change by 13 years and paving the way for Abbott to become prime minister. Have they learned nothing from that experience?

It’s hard to see the constitutional change getting up if people aren’t sure what they’re voting for, and are misled into thinking they are locking in a specific and detailed model, as implied in Dutton’s hectoring about “details”. The Resolve Political Monitor reports on people’s willingness to vote “yes” on “whether to enshrine an Indigenous Voice to parliament in the Constitution”. In August-September last year 53 percent answered “yes”, but by December-January that support has fallen to 47 percent, and the proportion of “undecided” voters has risen from 19 percent to 23 percent. When the “undecided” are forced to come off the fence and make a decision, just 60 percent vote “yes”, down from 64 percent in the earlier survey. That’s a slim margin before the “no” campaigners, unconstrained by any regard for truth, really get underway.

That same survey finds that only 13 percent of respondents understand the proposal. In fact almost a quarter of people surveyed have not even heard about the proposed Constitutional change.

We may speculate on the reasons for Dutton’s deceitful behaviour in conflating the referendum and legislation. Maybe he is trying to secure preferences from racist elements on the far right. Maybe he hopes that if this referendum fails, the government will not risk a referendum on an Australian head of state — the Coalition still holds a strong affection to the UK and its monarch. Maybe he is trying to show he is in line with the Liberal Party’s remaining supporters: the Resolve survey reveals that while at this stage only 30 percent of all voters are definitely “no”, 52 percent of Coalition voters are definitely “no”. Also, compared with voters for other parties, Coalition voters are least likely to understand what the referendum is about, or maybe they don’t understand the hardships faced by most indigenous Australians. The Essential Poll this fortnight reveals that Coalition voters are much more likely than Labor or Green voters to believe that the standard of living for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people has gotten better.

Dutton has said the government is treating us like mugs in not presenting draft legislation. It’s Dutton, however, who’s “treating us like mugs”, hoping we don’t understand the difference between the Constitution and legislation (the Liberals were never strong on governance or on principles). Attorney-General Dreyfus has asked Dutton if he supports the principles of an indigenous voice. Malcolm Turnbull supports the Voice. Former Coalition Indigenous Australians Minister Ken Wyatt is throwing his weight behind a Voice, as is MP Andrew Gee, who quit the National party because of its opposition. Liberal Senator Andrew Bragg says he would like to support the Voice but he believes the referendum proposal needs more legal scrutiny. (10 minutes on ABC Breakfast.) That’s a valid point, because he is talking about the wording of the constitutional amendment – the three sentences. But he has not joined in Dutton’s deceit.

Th demand for “details” seems to be less about the Coalition’s basic policies than about Dutton’s combative and polarizing way of doing politics. Maybe Dutton’s approach is just bastardry — an attempt to deny the government a “win”, and an affirmation that there is no political model other than a polarized and combative one. It’s back to the Howard-Abbott-Morrison model: if something is proposed by a Labor government, oppose it, regardless of its merits.

As Chris Wallace of the University of Canberra has written in the Saturday Paper, Dutton has used the opportunity to sew confusion about the referendum to dump his “reasonable man” persona and revert to form by “throwing red meat to the conservative base”: Albanese’s lesson in dirty politics.

Those who wish to see the referendum succeed would do well to explain the process, emphasizing that the referendum is about a basic principle, captured in three simple sentences, and that legislation, which will involve parliamentary debate, and which will undoubtedly be amended by subsequent governments, will provide for practical realization of that principle.

Barry Jones on our quaint Constitution

Our Constitution is anachronistic: in fact if it is interpreted literally, sovereignty remains centered in Britain, and as Section 117 asserts, we are “subjects of the King” rather than citizens of Australia.

They are some of the anachronisms Barry Jones finds in our Constitution, in his Saturday Paper contribution The Monarchy and the Constitution.

These anachronisms are more serious than quaint relics of an imperial past. Jones urges us to adopt an opening statement in the Constitution asserting Australian sovereignty, declaring Australia to be a democracy, and formalizing the powers of parliament and executive government (which lie dangerously unspecified in the Constitution).

He sees an inextricable link between Aboriginal reconciliation and the republic:

The monarchist cause is essentially the last expression of White Australia: its rhetoric, culture, ceremonials, politics and the habit of deference. It is a static, essentially nostalgic, position in a society that, although dynamic in some ways, is uncertain how to express itself. It is the politics of amnesia.

The republican cause is essentially multicultural, pluralistic, independent and irreverent – in a word, Australian.

Writing on the ABC website Nicholas McElroy summarizes the present situation in Australia’s long journey to having an Australian head of state: King Charles is Australia's new head of state. When could that change?. He reports on opinion polling revealing little enthusiasm for Britain’s Charles to be “King of Australia” – mustering only 35 percent support – but for now Charles bears that title.

The meaning of 26 January

Commonwealth Avenue, Canberra, 26 January

Essential in its latest fortnightly poll asks how we see January 26. For almost three quarters of Australians it’s just a public holiday or another working day. There are significant and predictable partisan differences, and older Australians are more attached to traditional Australia Day.

Aboriginal Australians, and many others with an understanding of our history have no doubt about the meaning of January 28. The chant at the Canberra demonstration was “Always was, always will be, Aboriginal land”.

One of Dutton’s mates?

Notably there was a sizeable anti-Voice sentiment. Those with such views seem to see the Voice as something designed by “white” Canberra bureaucrats, disconnected from 235 years of hard history endured by Aboriginal Australians and unaware of their present struggles.

The Voice is typical of arrangements that emerge in healthy democracies. Frustratingly slow for some, too radical for others. That’s its virtue.

The political campaign pursued by Dutton, the National Party and the Greens is less about opposition to the Voice, as about opposition to a political process that brings people together, making small steps at a time – the process so well understood by those who drafted the Uluru Statement. That process does not fit with the divisive strongman politics pursued by Dutton and his newfound allies.

January 26 is also India’s Republic Day. Maybe we will be able to celebrate Australia Day on the anniversary of our decision to become a fully independent nation, whenever that occurs. And it’s worth remembering that January 27 is Holocaust Remembrance Day – commemorating the day in 1945 when the Soviet army liberated Auschwitz.