Politics

Not just a new government, but new politics

“Something definitely happened on 21 May 2022” writes Katharine Murphy in her Quarterly Essay Lone wolf: Albanese and the new politics. Of course there was a change of government, but Murphy writes about the way politics in Australia has changed. We didn’t understand how it had changed until election night when we saw Labor win office with a record low vote and 16 seats were taken by “insurgents” as she calls Greens and independents.

The old two-party politics has been crumbling for many years. Many issues including gender and integrity in government do not easily fit into the old politics. The well-off and well-educated, who were once part of the Liberal Party base, have turned away from the Coalition.

Labor was able navigate in this environment in a way that the Coalition wasn’t.

Morrison’s behaviour certainly helped Labor, as the party’s own analysis confirms. But this was not like previous elections when Labor took office because people felt it was time to give Labor a run while the Coalition, the natural party of government, re-organized itself. Albanese and those around him have been able to present themselves as the natural party of government. If that perception of Labor holds it really is a new politics for Australia.

The Australian Election Study

The Australian Election Study covering the 2022 federal election has been released in three parts: the 2022 election report; a survey of trends revealed in 16 federal elections from 1987 to 2022; and a generous dump of data for those who look forward to spending their summer break doing correlations on spreadsheets.

The 2022 Report

Most media coverage has been about the 2022 report with comments on the unpopularity of Morrison and the source of the Teal vote.

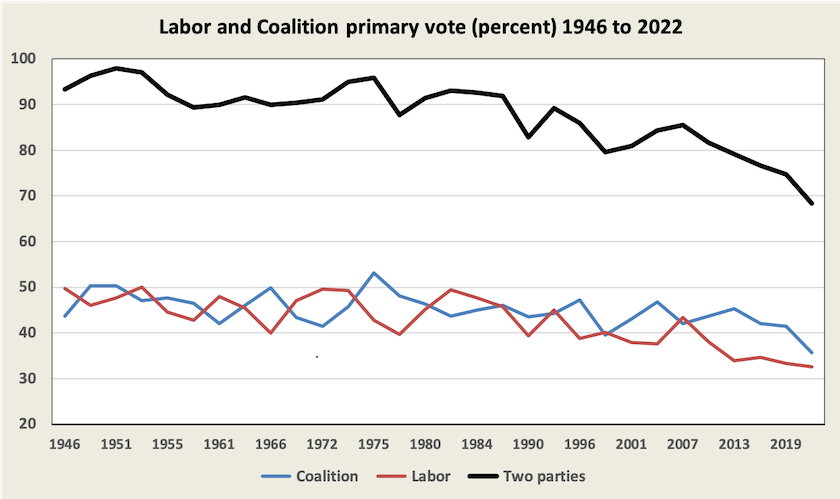

The main finding is the long-term decline in the vote of the two main parties since 1967. In fact, that decline has been in train since 1946, just after Menzies founded the Liberal Party, as shown in the graph below (which I previously presented after the election in May):

Some findings that don’t align with general perceptions, or that are particularly strong are:

- the unpopularity of Morrison, “the least popular major party leader in the history of the AES”;

- the characteristics of Teal voters who were not disaffected Liberal voters, but who were more generally tactical Labor and Green voters, wanting to see Morrison and other Coalition members out of office;

- contrary to some beliefs, the self-identified working class remains more likely to vote for Labor (38 percent) than for the Coalition (33 percent) – the working class has been drifting away from Labor but not necessarily to the Coalition;

- education was a strong correlate of voting in the 2022 election – 53 percent of those with tertiary education voted Labor or Green, compared with only 40 percent of those with “no qualification”;

- homeowners were far more likely to vote for the Coalition than renters – but it should be noted that home ownership correlates strongly with age, which means it is not entirely an independent variable;

- “the cost of living” was by far the most important issue influencing voters’ choice (32 percent), well ahead of “management of the economy” (15 percent) and “global warming” (10 percent);

- until the turn of the century women were more likely to vote for the Coalition than men, and the situation has turned around since – the researchers put this down to women’s participation in education and secularization, because in times past women were more likely to be religious observers than men, and therefore more conservative.

Perhaps the most significant findings relate to age. To quote from the study:

Only about one in four voters under the age of 40 reported voting for the Coalition in 2022. At no time in the 35-year history of the AES have we observed such a low level of support for either major party in so large a segment of the electorate.

The even more significant finding (which is also showing up in the Victorian election) is that contrary to earlier trends, as voters age they have not been coming back to the Coalition. Even those born after 1965 (57 years or younger) have not switched to the Coalition as they have aged. The Coalition still enjoys strong support from those over 57, particularly those aged 77 or more whose support for the Coalition grew as they aged, but as they die they are not being replaced by new Coalition supporters.

Another finding, which has been a consistent one in these studies, is that voters almost always rate the Coalition as better than Labor at “economic management”, but they rate Labor higher in important economic issues, including climate change and education. This reflects a poor level of economic understanding in the electorate, because it is hard to find any dimension of economic management where the Coalition succeeds.

Trends

The other report Trends in Australian political opinion presents about 130 time-series charts of long-term developments (1987 to 2022) under 11 headings. Below are summarized as dot points some of the more significant findings and those that may not align with our beliefs and expectations. They all point to a future where life is getting harder for campaign managers and for pollsters.

The campaign:

- unsurprisingly people were more likely to follow the election campaign through the internet rather than newspapers or TV, but that was still through mainstream news media sites – it is not such a big shift;

- there is long- term growth in people reporting that they have worked for a candidate or have donated.

Voting and partisanship:

- there is a long-term fall in adherence to “how to vote cards” for the House of Representatives, but most people vote above the line for the Senate (this has implications for preference deals);

- there is an increasing tendency for people to vote differently for the Senate and the House;

- there has been a strong fall, from 72 percent in 1967 to 37 percent in 2022, in those who always vote for the same party, with commensurate falls in the proportion of people describing themselves as “stable Liberal-National” or “stable Labor”.

Election issues:

- policy issues continue to be the main consideration in voting decisions; while party leaders and local candidates count far less (so why does the Liberal Party consistently refrain from re-examining its policies?);

- the Coalition is seen as better at managing the economy, but Labor is seen as better on education, health and global warming (does this mean people don’t see education, health and global warming as economic issues?);

- although there has been a great deal of discussion about global warming as an election issue, only 10 percent of respondents nominate it as an issue, but there is a strong belief that Labor will do better on global warming than the Coalition;

- there is no perceived difference between the parties on immigration and asylum-seekers (in spite of the Coalition’s beat-up of the issue).

The economy:

- in this election people were pessimistic about the economy overall and their own finances, but they didn’t think the government could make much of a difference;

- people expected to see increased public spending on health, education, unemployment benefits, pensions, and defence.

Politics and political parties:

- almost 80 percent of respondents claim they would have voted even if voting weren’t compulsory, but that figure has been falling over the years;

- there is a slow but long-term loss of affection for major parties, particularly the Nationals;

- people believe parties don’t care how people think;

- there has been a big fall in the number of people signing petitions.

The left-right dimension:

- people still conceptually line up parties on a left-right spectrum and if anything they see all parties shifting a little to the “left over time.

The political leaders:

- Bob Hawke wins the popularity contest, while Pauline Hanson, Joh Bjelke-Petersen (1987), and Barnaby Joyce struggle for last place, and Morrison edges out Billy McMahon as the most unpopular leader of a major party;

- in 2022 Albanese led Morrison on 8 out of 9 perceived personal characteristics – by very large margins on “compassionate”, “honest”, “trustworthy”, and “inspiring” (those who do well on these 9 characteristics tend to win the election, but people’s perception can change if the same person contests consecutive elections);

- people don’t like leadership changes, except for the time when Turnbull knocked off Abbott, when the attitude came close to 50:50.

Democracy and institutions:

- after a decline in 2016 and 2019, our trust in democracy is back up – this is significant because in many countries trust in democracy has been waning, and although our figures bounce around a fair bit, they show no sign of a long-term decline (we still show less trust in democracy than people in New Zealand and the Nordic countries, however);

- as in other countries, we show a long-term decline in trust in government and we believe government is run for “a few big interests”;

- there is still net support for a republic (54 percent) but the trend has been downwards for 30 years (the Queen of England died after the election);

- there is 80 percent and unchanging support for indigenous recognition in the Constitution – surveyed only in the last three elections;

- there is not much support for lowering the voting age to 16 (pity).

Trade unions, business and wealth:

- 40 years ago we thought unions had too much power but steadily this attitude has shifted – we now think big business has far too much power, (this shift in sentiment aligns with the shift in factor income towards profits and away from wages);

- apart from two percent of respondents who see themselves as “upper class”, we still see ourselves around 50:50 “working class” or “middle class”, in spite of a widening gap in wealth;

- although trade union membership is falling, we are becoming much less inclined to believe there should be “stricter laws for unions”;

- the percentage of respondents favouring less tax has fallen from 65 percent in 1987 to 39 percent in 2022, and about half of us think income and wealth should be redistributed;

- we still believe that high taxes make people unwilling to work, but the strength of this belief has been falling for many years.

Social issues:

- opposition to same sex marriage continued to fall after the plebiscite, while support for making abortion readily available has continued to rise;

- attitudes to crime and punishment have softened over the years (some may be surprised to learn that up to the turn of the century more than 50 percent of us believed there should be capital punishment for murder);

- the percentage of people who believe that government help, including land rights, for indigenous Australians “has gone too far” had tumbled form 55-59 percent in 1990 to 27-29 percent in 2022.

- most respondents still believe asylum-seeker boats should be turned back, but not as strongly as we did 20 years ago;

- our attitudes to immigration seem to go up and down with domestic economic conditions, but in 2022 we supported immigration strongly (suggesting that concern with skill shortages may trump house prices);

- around 80 percent of respondents support voluntary assisted dying.

Defence and foreign affairs:

- over the last 10 to 20 years we have become more inclined to believe that our country is inadequately defended;

- support for the “war on terrorism” has fallen since 2001;

- we have stopped being afraid of Indonesia and are now afraid of China, and there is still some residual fear of Vietnam, Malaysia and Japan and a slight rise in fear of the USA;

- in 2022 there was a sharp jump in the proportion of people who believed our relationship with Asia has been developed far enough.

More on the Liberals’ journey to oblivion

They are in deep trouble.

Mike Seccombe’s Saturday Paper article, written after the Victorian election – Inside the Liberal Party’s “existential crisis” – confirms much of what was covered in last week’s roundup, particularly its long-term decline in primary vote. He adds three other important points:

First, the Coalition can no longer rely on people becoming more attuned to its policies as they age. Conservatives once relied on the trend for older people to move to the right: as one cohort of aged supporters died off, another would fill their ranks. But there is strong evidence that this political conversion is no longer happening.

Age journalists Sumeyya Ilambey and Royce Millar show what this means in their article How Labor pulled off the sweetest victory of all. In just the last ten years the proportion of baby boomers in Victoria has fallen from 55 percent to 39 percent.

Second is the re-emergence of economic inequality as a political issue, but this time it is not so much about income (as it was in the past) but about wealth – owning a house, a share portfolio, a self-managed superannuation fund. Young people have become more politically engaged because they are generally asset-poor, and over-represented among renters. Seccombe could have gone on to make the point that so far they have been able to blame the Coalition’s policies for this situation, but in view of Labor’s dominance of the political landscape, as time passes intergenerational disparities in wealth are becoming Labor’s problem.

Third, Teals and independents have done well in the Victorian election. The Coalition is gloating that contrary to some media expectations the predicted Teal wave didn’t occur. The Liberals won Hawthorn, in the middle of the Kooyong federal electorate that Frydenberg lost to independent Monique Ryan, and held on to Kew, an adjoining seat contested by an independent. Also the National Party has taken two seats from independents. But as Peter FitzSimons points out in his account of an interview with Simon Holmes à Court, it’s short-sighted to focus on seat counts: Has the teal tide turned? The Fair Dinkum Department quizzed Simon Holmes à Court in The Sydney Morning Herald. The Coalition’s victories against independents were narrow, and the trend is away from the major parties. Ilambey and Millar, in the article referred to above, demonstrate the steady decline in the two-party Coalition plus Labor primary vote in Victoria: in 1992 it was 94 percent; in this election it was 72 percent.

As a metaphor, imagine a community living downstream from a dam, concerned about flooding. The water authority may report that the water is still a few centimeters below the spillway, but if it is rising that’s cold comfort.

Confirming the Liberals’ poor standing, William Bowe in his Poll Bludger reports on two national voting intention surveys, one by Newspoll and the other by Essential. The Newspoll shows a big rise in Labor’s support since the election but no significant fall in the Coalition’s support, while the Essential poll shows a big fall in Coalition support and no change in Labor support. Either way it’s bad news for the Coalition as we go into the end-of-year political doldrums.

The Newspoll has particularly poor approval and preferred PM figures for Dutton, and the Sydney Morning Herald reports on an even worse poll for the Coalition, showing Labor’s vote 9 percent up on its vote at the election and the Coalition’s down 6 percent. In terms of policies it shows Labor leading in all 17 policy areas surveyed, including economic management and national security, areas where the Coalition has almost always led. It also shows Albanese holding a huge lead as preferred prime minister.

David Crowe, commenting on the results, attributes some of Labor’s surge to voters getting to know Albanese and finding that the Labor government is not the ogre that the Coalition and the Murdoch media had warned us about. Have they blown their credibility?

Update on the Victorian election: In last week’s roundup my table of long-term reversals by the Coalition showed that in this election their primary vote has fallen by 0.2 percent. Later counting shows that the fall has been 0.5 percent. There goes another election myth, the idea that pre-poll, postal and absentee votes are biased towards conservative parties.