Economic policy

Is the Reserve Bank relying on stale data?

As most media expected, and as many independent economists feared, the Reserve Bank has raised the cash target rate by another 25 basis points to bring it to 3.10 percent. It has also announced that it expects to increase interest rates further “over the period ahead” (unhelpfully vague), even though it expects inflation to fall to “a little above 3 percent over 2024”.

In its press release it justifies its decision on the basis that inflation has been 6.9 percent over the year to October.

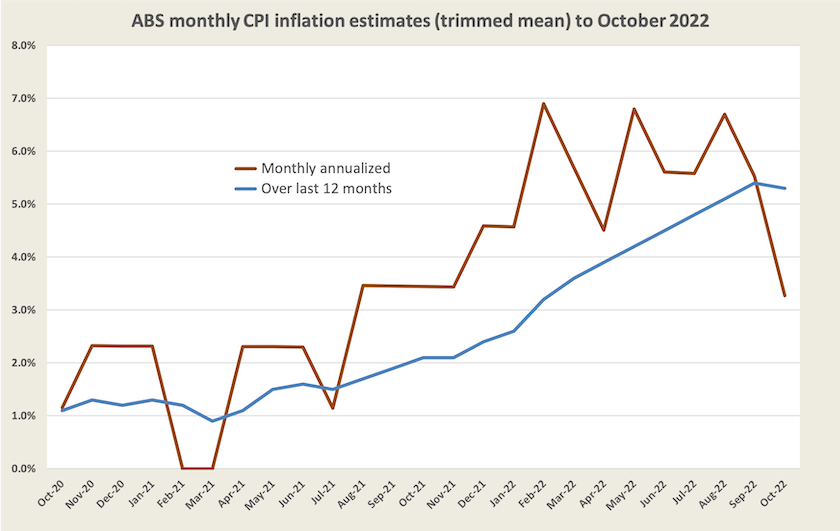

It seems to have picked from ABS statistics a number that is most likely to overstate inflation. That 6.9 percent is taken from the October monthly CPI indicator. That’s a headline figure, without any qualification. The trimmed mean estimate – a method that excludes high and low outliers and which the ABS sees as “an indication of the medium-term trajectory of inflation” – is only 5.3 percent.

And even that is possibly an over-estimate, because it picks up CPI inflation over the whole previous 12 months. If, for example, all the inflation had been in the half-year to April, with no inflation in the half-year from May to October, it would still be reading 5.3 percent (or 6.9 percent as the RBA has used).

In its attempt to rein in inflation, the Reserve Bank should be thinking what inflation will be in the near future, not what it has been in the past.

If one downloads the ABS monthly data and does a little straightforward analysis, it turns out that CPI inflation in October was only 0.27 percent, which would work out to around 3.3 percent if sustained over a year.[1]

That’s much lower than 5.3 percent, and is close to the Reserve Bank’s comfort range of two to three percent.

The graph below shows the difference between the retrospective year-to-date series (blue line) and the monthly series projected over 12 months (dark red line). The red line is rough – there is a significant margin of error in each month’s estimate – but it seems to be coming down, while the blue line is generally telling a story of rising prices.

Peter Martin, writing in The Conversation – This latest increase in RBA interest rates might well be the last, for some time – presents similar data, suggesting that the ABS monthly series could be indicating a fall in inflation. He also notes that some global commodity prices that have been feeding inflation have fallen, and that there are signs that consumer spending is slowing.

It is hard to understand what is driving the RBA to keep on pushing up interest rates. It “recognises that monetary policy operates with a lag” – so why hasn’t it waited to see if its moves so far have been effective, particularly when the most timely data available from the ABS suggests CPI inflation could be falling?

Also it’s strengthening the idea that inflation is high. As economics textbooks point out, and as the RBA occasionally states, expectations of inflation can be self-fulfilling: if people think inflation is high they will act collectively in ways that boost inflation. In picking a possibly-overstated indicator of inflation, the RBA is contributing to this expectation.

1. The seasonally-adjusted trimmed mean index numbers were 111.8 in September and 112.1 in October. That implies a monthly inflation of 0.268336 percent (112.1/111.8 = 1.00268336). Over 12 months that comes to 3.268 percent ( 1.00268336 ^ 12), or 3.220 per cent if one does not compound. ↩

National accounts – green shoots

At 0.6 percent for the quarter GDP growth was a tad below market expectations, but it is generally back on the pre-pandemic trend.

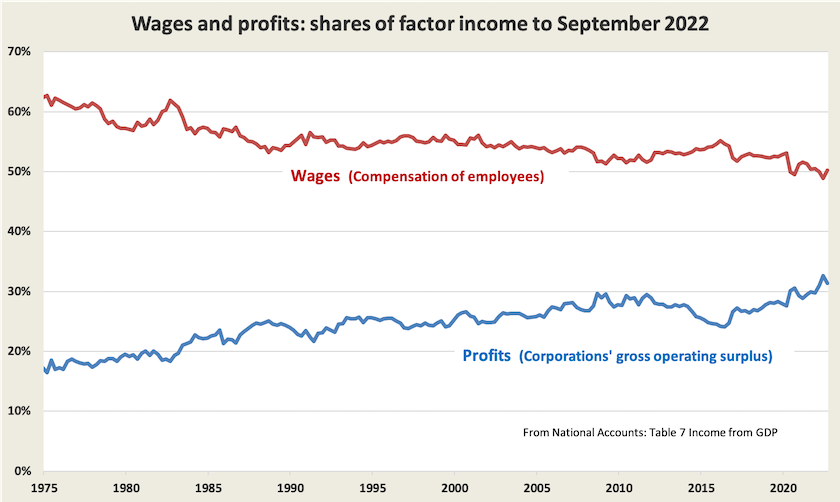

Wages, as measured by data on “compensation of employees”, showed the strongest rise for six years. In round figures wages in the September quarter rose by $9 billion, but those who fear there will be a wages-induced inflationary spiral can be reassured that this was mostly offset by a $6 billion fall in profits (“gross operating surplus of corporations”), most probably concentrated in the mining sector as commodity prices fell. Not that this means there has been a collapse in profits: the wages-profits division of national income still has a long way to go before it is back to what it looked like in past times. The latest quarter development shows up only as a small pair of ticks at the end of the graph.

The national accounts came out the morning after the RBA’s meeting at which it raised interest rates by 0.25 percent.

The national accounts figures lend weight to the suggestion that the RBA might have done better to hold off raising rates. The GDP implicit price inflator fell sharply. That’s an economy-wide indicator of inflation that covers more than the CPI which is based on household consumption. There was continued strong domestic demand, but much of that was for overseas travel and new cars, suggesting that much of consumers’ increased spending will be going overseas without over-stimulating the domestic economy.

All you need to know about competition policy

One way to learn the basics of microeconomics – competition, monopoly, productivity, consumer surplus and all that stuff – is to enrol in a class in Economics 1, and follow a lecturer drawing strange freehand graphs on a whiteboard.

Or you can spend 15 minutes listening to an interview with Andrew Leigh, Assistant Minister for Competition, Charities and Treasury, on last weekend’s Saturday Extra: How price parity clauses affect your wallet.

The discussion starts by looking at the practice by travel booking platforms such as booking.com and expedia.com, that prohibit hotels from offering prices on their own websites that are lower than the prices advertised on the booking platforms. Leigh cautiously suggests that such a practice is contrary to the spirit of competition policy.

The discussion moves on, first to the strong market power held by digital platforms – a matter that has been subject to an inquiry by the ACCC – and then to the issue of competition policy in Australia generally.

Leigh notes that in many sectors fewer new firms are starting up, and a greater share of the market is being captured by the biggest firms. The losers are consumers. Citing the benefits of the Hilmer Reforms of the 1990s (which he estimates increased household income $5000 a year), he calls for strong competition policy and for an improvement in our productivity performance, competition and productivity being closely related.

Andrew Leigh and Geraldine Doogue refer to a current Treasury inquiry specifically about online booking platforms. A discussion and an invitation to comment are on the Treasury website. It’s probably more productive to write a submission than to argue with a hotel receptionist asking for a discount. Submissions close on January 6.

Upbeat views on our transition to a zero-carbon economy

Over the last six months there has been a national shift in mood relating to our transition to renewable energy. The idea that dealing with climate change will come at a cost to our economy is giving way to excitement about the opportunities presented by our industrial transformation. Emission targets that until recently were seen as unduly burdensome or unachievable are now presented as quite realistic in the Commonwealth’s first Annual Climate Change Statement, which strongly suggests we can beat the 43 percent target for 2030 that Labor took to the election. (It’s a long report with heaps of data and lots of well-composed pictures. Sophie Vorath has a neat summary on the Renew Economy website.)

There is a similarly upbeat mood in an edited recording of a conference session on Australia’s energy transitions. Not only can we become zero carbon, but we can also become a renewable energy superpower. The session was chaired by Geraldine Doogue, with Ross Garnaut, Audrey Zibelman, and David Neal (a Melbourne-based provider of advice for superannuation funds) participating. An edited version of the session is included in last weekend’s Saturday Extra: Superpower of the zero-carbon world?. (29 minutes)

The transition is already underway, and it is not linear. Zibelman mentions the 2017 spat between Commonwealth Treasurer Josh Frydenberg and South Australian Premier Jay Weatherill when Scott Morrison tried to blame renewable energy for South Australia’s blackouts following a severe storm that had cut off the state’s large coal-fired station. That accusation saw a rapid reaction from South Australia, notably including installation of the world’s then largest battery at Jamestown, followed by initiatives in other states.

David Neal points out that the transition will require a huge investment, around 5 percent of GDP, for an extended period, but that should be no impediment: there is plenty of money sloshing around the world looking for somewhere to make safe investments in renewable energy, and that 5 percent is about the same as we invested during our transition to a mining-based economy.

Garnaut describes how renewable energy can move Australia to more processing of our raw materials, for example becoming globally competitive in steel made from our iron ore, using local renewable energy for reduction and heating. By its physical nature, renewable energy gives a big competitive advantage to industries that can use it locally.

This upbeat outlook is not confined to Australia. The International Energy Agency sees the energy crisis resulting from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine as having sharply accelerated the world’s transition to renewable energy in its report Renewables 2022. The world is set to add as much renewable power in the next 5 years as it did in the past 20.

Homelessness

The Australian Homelessness Monitor covering the 2021-2022 year came out early last week, and it paints a grim picture. Its main findings are in a Conversation contribution by Hal Pawson and Cameron Parsell: Homeless numbers have jumped since COVID housing efforts ended – and the problem is spreading beyond the big cities.

Homelessness can result from many misfortunes, including marriage breakdown, floods and fires, and unemployment, but this research identifies housing affordability, particularly inflation in rental prices, as the main cause of worsening homelessness.