The Lamentations of the Liberal Party

Victoria’s election

The Coalition’s long-term decline

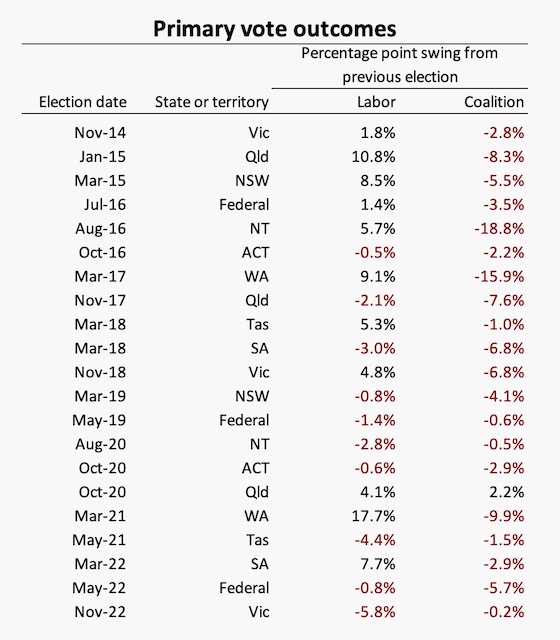

In the last eight years there have been 21 elections – 18 state, 3 federal.

In all but one of these elections the Coalition primary vote has gone backwards.[1] Victoria’s outcome is simply a continuation of this losing trend, shown in the table below.

Not that Labor’s primary vote was too flash in this election: we’ll come back to that next week when counting has progressed.

The National Party is claiming bragging rights, because it picked up 3 seats, while the Liberals lost 1 (preliminary results). Also the Nationals’ primary vote was up by 0.3 percent, while the Liberals’ vote went down by 0.5 percent.

Two of the three seats the Nationals gained – Mildura and Shepparton – were won from independents, but not by large margins. The media are reporting the election outcome as a reversal of the swing to independents in the federal election, but that’s lazy journalism. In terms of primary votes, independents and small parties were the winners, their support having risen from 11.3 percent in 2018 to 17.0 percent in this election. If we were to classify the Greens as a small party, that rise would be from 22.0 percent to 27.9 percent.

The media get excited about seats won or lost, but those figures in themselves rarely reveal much about trends among voters. Seat contests are often determined by local issues, the quality of candidates, and the contestants’ seat-by-seat tactics. Parliamentary majorities count in the short term: who could deny, for example, that Labor’s narrow win in 1972 and its narrower win in 1974 were highly consequential. But the long-term trends are revealed in voting percentages, particularly primary votes.

In fact it’s been a poor outcome for both main parties. In terms of seats, independents have gone backwards, but as has happened federally, as their support reaches certain thresholds, there can be a large gain in terms of seats. Journalists who cannot think beyond a football game metaphor (where the winning margin doesn’t count), seem to be oblivious to the trend: nationally and in the states the old two-party “Westminster” system is giving way to multi-party parliaments.

Murdoch media another loser, polls another winner

A number of Conversation articles comment on the vituperative denigration of the Andrews government in the Murdoch media, often manifest as ad-hominem attacks on Andrews himself.

Denis Muller of the University of Melbourne has two articles on the Murdoch media’s political strategy. The first – Attacks on Dan Andrews are part of News Corporation’s long abuse of power – presents a long-term history of the Murdoch media’s political involvement in Australia. He writes:

The starting point is that the Murdochs – Lachlan or Rupert or both – clearly prefer a non-Labor government, and the continuance in office of a Labor administration in Victoria is an offence against their wishes.

He then goes on to describe some of the Herald-Sun’s “bizarre coverage” of the election.

His second article – Media go for drama on Victorian election – and miss the story – describes a less-intentional bias in the media generally. Once a story starts circulating, even if it emanates from a biased source, it quickly gets picked up by other media, who may add their own perspective, but it’s often in the form of angles that add to the original story – an example of the confirmation bias in action.

The story in this case was that Victoria was heading to a tight election, with the two parties neck-and-neck in the final outcome. Reputable media, including The Age and the ABC bought into the story. “How could the pre-election coverage have been at once so breathless and misleading?” Muller asks, suggesting that “the short answer is because of a combination of groupthink and wishful thinking”. (I confess that in last weekend’s roundup I suggested that a minority government was a probable outcome.)

Also the drama of a tight contest attracts media audiences.

Another explanation may lie in the way people often mistake noise for effectiveness, a phenomenon well-researched by behavioural economists. During the pandemic and into this year, Melbourne has experienced some angry and noisy demonstrations against the Andrews government, creating the impression that there has been a huge people’s protest movement. But such a sentiment has not shown up significantly in opinion polling. A thousand people on the streets of Melbourne is only 1 person in 5 000. Real people’s power movements that topple governments do much better than that.

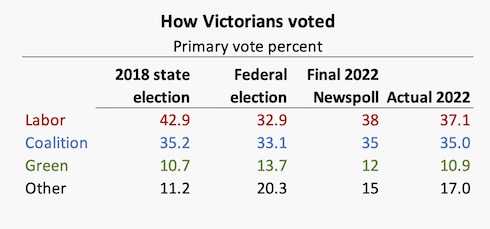

Adrian Beaumont, in his usual unexcitable style, pointed out that the polls were generally giving accurate predictions, including seat outcomes: Final Victorian Newspoll gives Labor a large lead. That Newspoll, confirming earlier polls by other outfits, gave Labor a 54.5:45.5 TPP lead, which is very close to Antony Green’s 54.2:45.8 outcome (with 73 percent of votes counted).

The table below shows that the final Newspoll was also very accurate in its primary vote prediction. It understated the “other” support a little, but that is an unavoidable bias in polling, because polling depends on respondents’ ability to recall a name.

Beaumont also has an article based on the count to date: Labor easily wins Victorian election; Greens on track to win four lower house seats. He includes some tentative estimates for the upper house, suggesting that parties that can loosely be described as on the “left” will probably pick up about 23 of the 40 seats. It’s disappointing that the media tend to ignore upper-house votes, because as Australian history shows, many Labor governments, holding a lower-house majority, often have their legislative agendas blocked by right-wing majorities in the upper house.

Policies – still a no-go zone

A feature of election-night broadcasts is that hardly anyone dares mention the word “policy”. True to form in this election, as the poor results came in the Coalition tended to blame the media (a hard one when the Murdoch media is 100 percent on their side side), the “leader”, their own campaign strategy, and the other contestants’ deviously cunning campaigns.

The ABC’s Richard Worthington picks up the way the Liberals see the outcome in his article: Victoria's election holds lessons for Labor, but it's the Liberals who now face the challenge of reform. The Liberal “brand” is damaged (our table of outcomes over 21 elections confirms this). Their strategy of trying to harvest votes in what were once Labor working-class heartlands produced no net benefits. And now they are groping around for a “leader” to take them out of the wilderness.

When people call for a strong “leader” it’s a sign of a lack of confidence and a failure to face up to the group’s own inadequacies.

Mark Kenny, writing in The Conversation, suggests that the Liberal Party has become too close to right-wing extremists: Victorian Liberals embarrassed by extremists within: how does this keep happening? He mentions those who rally around the brand name “Christian” (a word that has little connection with the moral teaching of Christians’ New Testament), as a cover for racism, opposition to action on climate change, and an obsession with controlling people’s sexual behaviour. He might also have mentioned the party’s preferences, suggesting people put Labor last, behind extremists who have shown open contempt for democratic traditions and institutions. That may look like a clever way to pick up those last few crucial votes, but for every vote it picks up from those who loyally follow the how-to-vote card, it probably loses more from those who are disgusted by the message that the party keeps bad company.

The Guardian’s Josh Butler describes how Coalition politicians have gathered to hear anti political-correctness culture warrior Jordan Peterson preach about the threat to our way of life from the woke left. Do not these people who rush to right-wing forums realize that those who count themselves as “left”, “progressive”, and those who live in same-sex relationships, are generally as boringly suburban, conformist and unthreatening as those who consider themselves on the “right”?

Shaun Carney of Monash University sees some longer-term changes that help explain Labor’s ongoing success. His Conversation article is titled How Dan Andrews pulled off one of the most remarkable victories in modern politics, but that’s a poorly-chosen title, because it’s more about big trends in Victoria:

Gentrification, the decline of manufacturing, the rise of the knowledge worker, the emergence of health services and tertiary education as important industries, digital communications, rising waves of Asian immigration – all of these have taken place over those 40 years. The Labor Party has managed to adapt to the state’s transformation much more effectively than the Liberals.

Some tentative conclusions/speculations

Until the vote is fully counted there won’t be much meaningful analysis of the results. (There may be some analysis by next week’s roundup, my last for the year.) And it will be some months before political scientists do their multivariant analysis to detect what influenced people’s votes. At this stage, a few possible trends seem to be emerging, and they will probably provide hypotheses for political scientists to test:

- The Liberals’ comparative success in the northern and western suburbs may simply reflect these areas becoming more like Melbourne as a whole – what statisticians call a “reversion to the mean”.

- Maybe the harshness of Victoria’s Covid-19 response contributed to the swing in northern and western suburbs. In these regions there was a concentration of resistance to vaccination, and there were many angry voices protesting against public health regulations. Also they were probably over- representative of people in occupations that were most exposed to the Covid-19 risk. But in the pre-election speculation any such reaction seems to have been overstated. The general impression in Australia and worldwide is that while people have disliked lockdowns, they have not punished governments for having taken strong public health measures. (In this context it is notable that right-wing parties capitalize on people’s fear of terrorism, while generally dismissing their fear of deadly diseases.)

- Large cities close to Melbourne, such as Ballarat, Bendigo and Geelong, seem to be going in the same political direction as Melbourne. By contrast Labor and the Greens have done pathetically in more distant regions – even in Mildura, a city of 90 000 population, they have won only 6.0 and 2.2 percent support respectively. The political and journalist establishments should stop using the term “regional” as a classifier for everything outside our capital cities. Rather they should do the hard work of studying political trends in all our regions, including those within our big cities, such as western Melbourne.

- The Liberals’ economic policies were flaky. They were promising to cut spending on public transport infrastructure and to redirect it to health. There is plenty of survey data confirming that people want to see more money spent on health, but maybe people are uneasy about seeing capital expenditure being re-directed towards current services. That fails both the pub test and the maxims of good financial management.

Neither of the major parties seems to be facing up to the fact that Melbourne is a rapidly-growing city (about to overtake Sydney), and as such will need to spend heavily on infrastructure and on services. In such a situation it is quite legitimate for governments to borrow heavily provided it’s to finance assets: that’s a normal balance-sheet approach of financial management.

1. In Queensland’s 2020 election the Coalition’s vote recovered a little from its disastrous 2017 performance, when One Nation won 13.7 percent of the vote largely at the expense of the Coalition. The 2020 recovery of 2.2 percent was insufficient to allow the Coalition to win office. ↩

Morrison’s censure: of course it’s partisan political, but it’s also about a violation of our democracy

The media have more than adequately covered the theatre of Scott Morrison’s censure, including the way all but one Coalition Member, regardless of what they might have said earlier, have closed ranks to support Morrison and how most have staged a petulant walkout from Parliament.

Michelle Grattan has a brief article in The Conversation, providing some background to the process, and another written after the censure summarizing different politicians’ stances in the parliamentary debate, but both are in the style of journalism rather than any serious analysis.

The Coalition may call the censure a “stunt”, but that’s to belittle the significance of Morrison’s behaviour because it bypasses the normal limitations of political power that prevent the prime minister from behaving like an elected dictator, and completely disregards the primacy of Parliament.

This significance is picked up in House Leader Tony Burke’s formal motion on the censure, recorded by the ABC as a short clip. Drawing on Justice Virginia Bell’s findings, Burke states the general condition calling for a censure, namely “that he fell below the standards expected of a member of the House”. Burke goes on to the specific aspects of Morrison’s behaviour:

The actions and failures of the Member for Cook (1) fundamentally undermined the principles of responsible government, because the Member for Cook was not responsible to the Parliament, and through the Parliament to the electors, for the department he was appointed to administer and (2) were apt to undermine public confidence in government, and were corrosive of trust in government, and (2) [again] therefore censures the Member for Cook for failing to disclose his appointments to the House of Representatives, the Australian people, and the Cabinet, which undermined responsible government and eroded public trust in Australian democracy.

Of course Labor is enjoying a touch of Schadenfreude, and is not letting a chance to embarrass the Coalition go by, but it’s also a serious matter, as David Crowe wrote in the Sydney Morning Herald: The compelling case for parliament to condemn Scott Morrison, bringing together the partisan and constitutional issues around Morrison’s actions. As Laura Tingle writes, The Bell inquiry shreds Scott Morrison's credibility and for Labor the timing couldn't be better.

The Guardian’s Paul Karp covers the main issues in a post: “Eroded public trust”: text of Scott Morrison censure motion revealed as colleagues back former PM. His post includes a short clip of Albanese’s rebuttal of the Coalition’s dismissal of the censure, the text of which reads:

I note the rather extraordinary comment by the manager of opposition business, who has said that the issue of the relationship between the former PM and his ministers is a matter for them. This wasn’t about the relationship between the former Prime Minister and his ministers, a sort of personal relationship between two mates over what happened down the pub. This is about accountability of a democratic system and whether the parliament was functioning properly and about the relationship between the Prime Minister and the people of Australia, who expect to be held to account through our Parliamentary processes.

The one Coalition member who supported the censure was Liberal MP Bridget Archer, who joined Labor, Green and independent members to speak in favour of the censure, describing Morrison’s actions as an “affront” to Parliament and to the Australian people. Also frontbencher Karen Andrews abstained from the vote.

Such are their political instincts that other Liberal Members of the House of Representatives, in a show of contrived solidarity, huddled around Morrison. They would do far better to reflect on their own behaviour in having supported him in the coup against Turnbull in 2018. What is it that led them to follow him so blindly?

Niki Savva on Morrison – and the Liberal Party

Former Liberal Party minister Fran Bailey suggested that Scott Morrison was “missing that part of the brain that controls empathy”.

That quote is an extract from Frank Bongiorno’s Conversation piece “He was woeful”: in Bulldozed, Niki Savva catalogues Scott Morrison’s nasty, duplicitous, nutty behaviour.

It’s a review of Niki Savva’s book Bulldozed: Scott Morrison’s fall and Anthony Albanese’s rise.

In light of what has been revealed around the censure motion, Savva’s account of Morrison’s shortcomings seems to be almost redundant. But it’s still an important contribution to our understanding of the times we are living in.

Its credibility is strengthened by Savva’s background. She is no leftie or a disgruntled former employee seeking revenge. In fact she was senior media adviser to Liberal Treasurer Peter Costello. She hails from the Liberal Party camp.

Importantly her work is not just about Morrison. It’s partly about the “Canberra bubble”, where “spineless senior public servants” meekly go along with agendas set by executive government. She also mentions the Governor-General in this context.

It’s also about the party that has allowed Morrison to lead it to ruin:

This Liberal Party now lies in tatters, captured by minorities of cranks and extremists, beholden to fossil fuel interests, and with increasingly tenuous links to the lived reality of the nation. Many of its leading members denigrate the values and lifestyles of those they need to support them. The party has a massive problem with women.

Savva’s work is a useful contribution, but there is a risk that we will come to see Morrison as the embodiment of all the Liberal Party’s woes. He could become the scapegoat for that party’s troubles, while it blunders on unreformed.

Morrison lacked compassion, insight and empathy. But we all should be guided by these moral virtues, and understand what he must be going through – to empathize but not necessarily to sympathize with him. Here is someone whom our political processes allowed to occupy a position that was way beyond his capabilities, and for which he was eminently unsuited. In any corporate setting the selection panel should take some blame for a poor choice.

We need to reflect on the processes that allowed Morrison to become prime minister, and on the political culture that led half of Australian adults to confirm that appointment in 2019. Labor stalwarts may enjoy watching Liberal Party suffer a slow death, but the space on the centre-right needs to be filled, possibly by a reconstituted party following Menzies’ example in 1944. Otherwise that space will be occupied by some far-right authoritarian populist movement, as has happened in other once-strong democracies.