Other public policy

The Reserve Bank comes out fighting – against inflation or against wages?

At his annual address to CEDA, Reserve Bank Governor Phillip Lowe made it clear that his main concern is “the scourge of inflation”. His argument is that historically, a bout of inflation is generally followed by a rise in unemployment that takes a long time to subside. It’s an assumption that economic history will repeat itself, and a value judgement that it is better to persist with our distorted wage relativities than to bear the risk of higher unemployment.

Yet he also points out that in the medium term inflation is likely to subside as the world recovers from Covid disruptions, as commodity prices fall, and as recent interest rate rises take their effect in world economies.

Is the RBA over-reacting, risking the instability that ensues when a powerful but slow-acting control (the interest rate) is applied too rapidly?

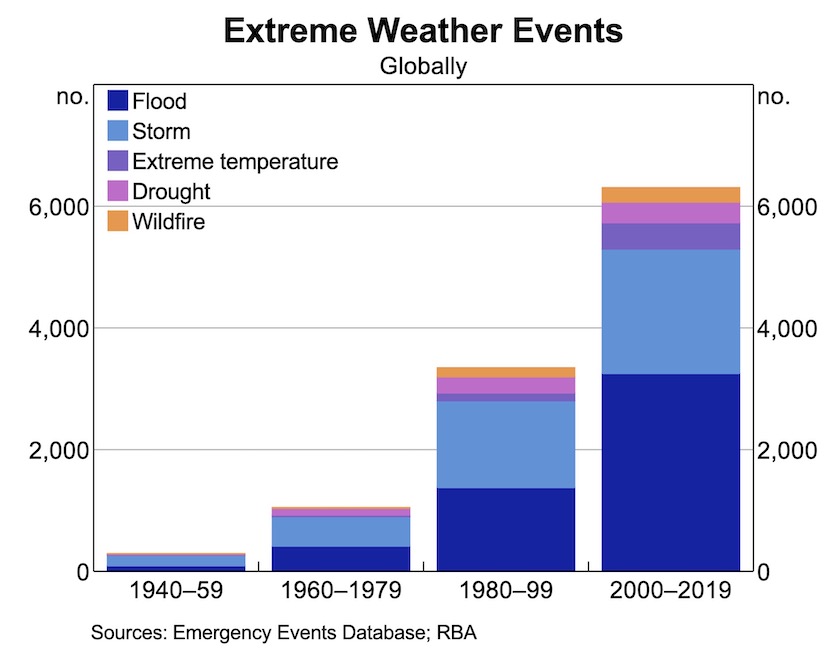

The rest of his address is about long-term economic developments, world-wide and in Australia. His presentation covers developments in world trade, demographics, climate change, investment in mineral resources and productivity. For the most part these observations are not new, but his message is that they combine to suggest both a lower trajectory of growth in “developed” countries, and that they increase the likelihood of significant disruptions. In that context his presentation of worldwide extreme weather events over the last 80 years is revealing:

Who’s afraid of the WTO?

WTO Director-General Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala is in Australia where she will deliver the annual Lowy Lecture on foreign affairs. In a short (8 minute) chat on the ABC’s 730 program she talks about the importance of an open world trading system. Trade is about people’s living standards and sustainable economic development.

She dispels the notion that the world faces a binary choice between protectionism and brutal open-slather global competition. She also sounds a warning about bilateral trade deals: your friend today may not be your friend tomorrow.

She is passionate about the need for countries to tackle climate change, asserting that “trade is the missing piece in the climate change fight”. She sees nothing wrong with countries putting a price on carbon-emitting products (such a price being a means to bring externalities into account, rather than a protectionist restraint on trade). She believes Australia would be well advised to make its way out of coal and to move strongly on green hydrogen.

She is also enthusiastic about a “loss and damage” fund for developing countries to them help them deal with damage resulting from climate change, a process in which Energy and Climate Change Minister Chris Bowen has been heavily involved. He explains how it is developing in an interview on ABC Breakfast.

In a strange incident in Parliament, Opposition Leader Dutton criticized the government strongly for endorsing a fund that will send money overseas. “Doesn’t charity begin at home?” he asked, referring to people struggling with living costs.

It is doubtful if anyone with a grasp of basic economics would have asked such a question. As the Reserve Bank stresses, and as most economists point out (particularly those who are economically conservative) it would be unwise to stoke our domestic economy with any more spending: we have an inflation problem. At the same time we have a healthy balance on current account, and a low and declining percentage of national income spent on foreign aid. It is hard to imagine Josh Frydenberg, had he kept his seat and become Opposition Leader, displaying such economic ignorance. He was an unapologetic neoliberal, but he knew his basic economics.

The cost of addiction

Addiction is costing Australia $80 billion a year. That’s around $8 000 per household in back-of-the-envelope round numbers.

Rethink Addiction has partnered with KPMG to calculate the cost of four forms of addiction – tobacco, alcohol, other drugs and gambling – publishing their findings in a report Understanding the cost of addiction in Australia.

Their methodology is conservative, being mainly confined to directly-traceable costs. They have a stab at calculating the opportunity cost of addiction – the benefits we would have enjoyed but for addiction – and that conservatively adds another $48 billion a year.

Different addictions manifest their costs in different ways. Alcohol and tobacco result in a significant cost to workplace and household productivity, other drugs impose costs on justice and law enforcement, and about half the costs of gambling fall on the individual in terms of “harmful consumption” – spending in excess of what would provide normal satisfaction.

Notably tobacco is still the biggest component of the cost of addiction – $36 billion out of the $80 billion. This is in spite of the rate of daily smoking having fallen to just 11 percent of adults.

(The link above does not work well in all browsers. For more clarity you can download the report as a PDF.)

A short history of the NDIS

There’s a lot of noise about the NDIS, particularly alarmist stories about its budgetary costs, rising at 14 percent a year, projected to cost $50 billion by 2030. There are also stories about fraudulent behaviour by providers, ridiculous amounts of bureaucratic complexity, and people with established needs having to wait years for attention or missing out altogether.

NDIS goes back to 2010, when the Rudd Government sent a reference to the Productivity Commission, asking it to report on options for a “national disability long-term care and support scheme”. It was to be for people with “severe or profound disability”; “to cover people with disability not acquired as part of the natural process of ageing”; and to assist people with disability “to make decisions about their support”. Importantly it was to replace existing funding systems. The Commission reported in July 2011.

On the ABC’s Rear Vision program three guests – Lorna Hallahan of Flinders University, Helen Dickson of the University of New South Wales, and Angela Jackson of Impact Economics and Policy – take up the NDIS story from 2012 when the Gillard government committed to go ahead with the scheme, initially trialling different models in different regions. Because the NDIS had strong popular support, the Abbott government, elected in 2013, decided to roll it out as a national scheme from 2016.

The Rear Vision guests describe the huge transformation, particularly for beneficiaries, in going from the previous schemes where funding came from appropriations to providers, to an insurance model, where funding was to be in the hands of the beneficiary, with some agency for them to choose what was most appropriate for their needs.

It has certainly cost more than was budgeted, but care should be taken in any calculation, because it partly displaces other funding previously provided through state governments and compulsory insurance schemes. In addition it was always going to involve a net fiscal cost: the Commission in 2010 estimated that its gross cost would be $13.5 billion a year, of which $7.0 billion would substitute for existing expenditures, resulting in a net fiscal cost of $6.5 billion. One of the basic design principles of the NDIS is that disability benefits should relate to the nature of the disability, not to happenstance – such as the difference between falling off a ladder at a construction site and falling off a ladder at home. Filling in such gaps has resulted in an increase in costs.

Another part of the extra cost has come from an original underestimate in the number of people who were to take up the program (originally estimated at 410 000, now 530 000). And another large part has been high administration costs – bureaucratic overheads, excess profits taken by providers, and in cases outright fraud by some of the scheme’s 9000 providers. Many of the providers’ staff have been employed by labour hire companies, adding another layer of overheads, and the situation has been aggravated by the Coalition’s imposition of staff cuts on the NDIA (the NDIS’s administrative body), requiring the employment of contractors. Then there have been the costs of defending appeals to the Administrative Appeals Tribunal.

As a result of fragmentation of funding among so many providers, the quality of service provision has been highly variable. Also, as in any benefits program with complex criteria for eligibility, those who can navigate the bureaucracy do better than those who are unfamiliar with the system.

These are all matters to be taken up in the forthcoming review of the NDIS. It ain’t broke, but it could deliver much better value for money.

Covid-19 in Australia and worldwide

Australia

The ABS has confirmed some of our impressions about Covid-19: it has been toughest on the oldest and the most disadvantaged, but it is becoming less deadly.

These are the general findings of its report Covid-19 mortality by wave, which analyses deaths by age, socio-economic status, country of birth, state, and pre-existing conditions. It also disaggregates much of this data by wave – Wave 1, Wave 2, Delta, and Omicron, with month-by-month analysis of the Omicron wave up to August this year.

The ABS report makes most sense if the progress of the pandemic is interpreted in two, or even three, parts. The first part, comprising the first two waves, was essentially pre-vaccination, up to mid-2021. Fewer than 1000 people died, thanks to strong public health measures. Then there were more deaths in the Delta wave in the second half of 2021. Up to the end of 2021 most deaths were in Victoria.

Most deaths have been this year in the Omicron wave – 8 000 out of 10 000 total. In the 8 months up to August, although Omicron has spread widely and quickly it has generally become less deadly for all age groups. As it becomes less deadly for the young, deaths have become concentrated among those over 80, and among those with acute or pre-existing chronic conditions. That aligns with the general impression that it has been causing less stress on the health system than earlier waves.

In all waves people of lower socioeconomic status have experienced disproportionately high death rates. Also, up to the end of the Delta wave, people born overseas had a significantly higher death rate than native-born Australians. This is possibly a reflection of the occupation categories of recently-arrived immigrants.

It is striking that the lowest death rates over the course of the pandemic have been in Western Australia and Tasmania, states with geographies that made border closure easy in comparison with Queensland, New South Wales, the ACT and Victoria. South Australia too has had a comparatively low death rate. Western Australia’s comparatively high vaccination rate may have also contributed to its low death rate.

Unfortunately vaccination is not one of the variables the ABS has considered. Presumably the data from state health authorities has been too unreliable to allow for any meaningful cross-tabulation.

The ABS records that there have been 178 deaths among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, but this does not cover Victoria, Tasmania or the ACT. Guardedly, one may conclude that a feared severe outbreak among indigenous Australians has not occurred.

The ABS properly confines itself to presenting statistics, leaving policy interpretation to others. But this publication tends to confirm that both the Commonwealth and the states and territories, in response to their geographic situations, generally made wise decisions over the course of the pandemic.

While the general interpretation from this publication is that Covid-19 is becoming far less deadly, it is still a serious disease for many.

The government’s weekly report of case numbers to November 22 show that new cases are still rising but are showing signs of levelling off, hospitalizations (the number of eople in hospital with Covid-19) are rising, and deaths have stabilized.[1]

Worldwide

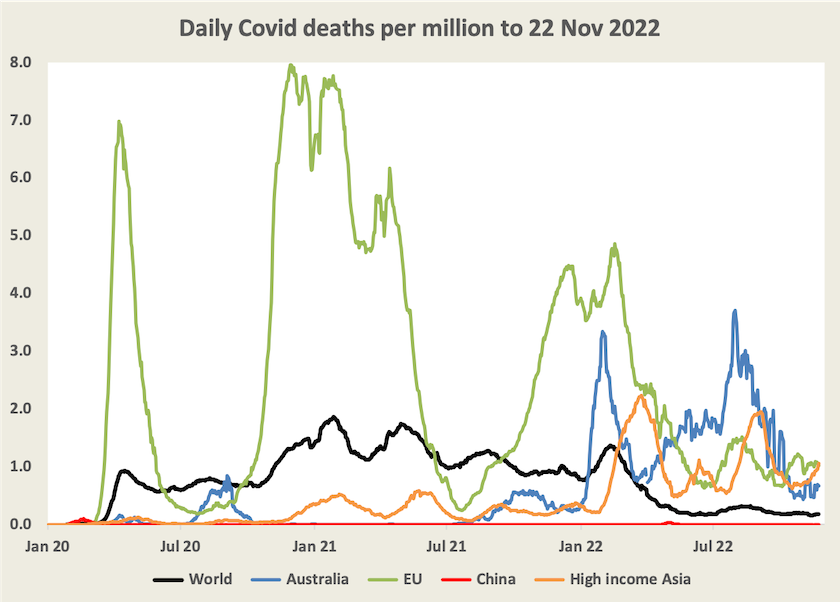

The path of this pandemic has been very different in different countries. The graph below, drawn from WHO data, shows pandemic deaths per million since its first detection for the world, the EU, high income Asia (Japan, Singapore, Korea, Taiwan) and China. (The US and the UK are not included because their inclusion would be off the scale.)

The world figures would be vastly understated, because of poor reporting from

“developing” countries, but they give a reasonable indication of the pattern of Covid deaths, which is echoed in the EU pattern.

In our region, Australia and high-income Asian countries, Covid deaths have been fewer than in Europe, and have occurred much later. This probably reflects the effect of strong public health measures in these countries in the pandemic’s early stages, before vaccination was rolled out.

China appears as a red line only occasionally popping its head above the axis but it is now dealing with what looks like an uncontrollable outbreak. It is hard to imagine how Covid-19 will develop from here on in a population that so far has hardly any immunity from earlier infection and is lagging in vaccination, particularly among vulnerable older people. Whatever happens – continued tight control, or a breakout, there will be some adverse economic consequences for China and therefore the world.

1. The case number data is not up to the ABS standard because it is subject to many inaccuracies and biases, but it still gives a reasonably good impression of the trend in cases. ↩

Whatever has happened to Medicare?

Our health care system, based on the principle of universality, has generally recovered from direct frontal assaults. The Fraser government demolished its first incarnation, Medibank, in the early 1980s, but in 1983 the Hawke government resurrected it as Medicare. The Howard government tried to kill Medicare by pouring taxpayer funds into subsidizing private health insurance, but the Coalition was to learn that Medicare is sacred when the “Mediscare” campaign almost threw the Coalition out of office in 2016.[2]

The greater threat to Medicare comes from long-term underfunding of its key elements. In his Policy Post Martyn Goddard shows how basic health services have become unaffordable, particularly for the young and the poor: Need health care in Australia? Just try not to be young. He covers all areas – GP services, pharmaceuticals, specialist services, dentistry and mental health, showing how health care has become so expensive, and that many people are avoiding health care because of cost.

Policymakers generally think in terms of ensuring that health care is available for the aged, who are the heaviest users of health care. But Goddard challenges that priority, revealing that those most likely to avoid seeking health care because of cost are the young. By contrast the old seem to have few financial barriers to finding health care. (This is unsurprising when one considers the ways the young are cajoled into subsidizing the old through the lifetime rating scheme built into the subsidies for private health insurance.)

Cost is not the only barrier for young people: he also points out that young people generally have to wait longer to see a specialist than older people. (Again, unsurprising, because subsidies for private health insurance have helped draw specialists away from public hospitals, providing them with an assured market among the wealthy aged.)

2. The “Mediscare” campaign was deceitful. It was based on Coalition proposals to privatize Medicare’s payments system, and other changes that would not have changed Medicare’s basic design. But there were other ways, more difficult to explain to the electorate, in which the Coalition was moving to kill off Medicare as a universal scheme. In a media environment where complex arguments and evidence are hard to present, a scare campaign with grossly simplified messages is an effective fall-back. ↩

How Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island Australians and other Australians relate

Reconciliation Australia has produced its 2022 Australian Reconciliation Barometer, presenting a mixed message about the relationship between First Nations people and other Australians.

When its findings are compared with those of similar surveys in 2018 and 2020, there are some signs of progress. It finds that “Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have experienced less racial discrimination in the last 12 months in interactions with professionals in public settings compared with 2020”, but 60 percent of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander respondents report having experienced at least one form of racial prejudice in the last 6 months, and that is a significant increase over 2018 and 2020.

The survey reveals that although there is a fairly high level of trust between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and other Australians, there is not a great deal of social mixing. Another finding is that most Australians are familiar with historical matters – frontier wars, stolen children, slaughters, and denial of voting rights. Familiarity varies between 63 percent for frontier wars, and 80 percent for voting rights. Some may point to the gaps, but in view of the neglect of these issues in education curricula until recently, and the fact that many immigrants would be unfamiliar with Australian history, these figures represent progress.

Some indicators have gone backward. This may simply be a result of sampling error, but it can be said with more certainty that there is no general evidence of significant progress since 2022.

In response to questions, framed in different ways, about support for a constitutionally-enshrined indigenous body, there is strong support (79 percent or greater) expressed by both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and other Australians.

Youth crime in northern Australia – what we’re doing isn’t working

Anyone who watched the Four Corners program Locking up Kids would be horrified by its depictions of physical brutality inflicted on children caught up in the criminal justice system in Western Australia and the Northern Territory. By any objectives of criminal justice – rehabilitation, deterrence, restitution for victims of crime, protection of the community – what the authorities are doing isn’t working. And it’s costly.

A group of academics in a Conversation article summarize the Four Corners program, with the conclusion that locking up kids has serious mental health impacts and contributes to further reoffending, essentially repeating a judge’s statement quoted on the program “When you want to make a monster, this is the way to do it”.

There’s far more to the story than was covered in the program. It gave scant attention to the victims of crime – the individuals who have their businesses trashed, and their vehicles smashed, all for no apparent purpose. It is easier to understand the motives of kids who raid cash registers to buy drugs or steal grog than it is to understand the forces driving wanton destruction.

The community-wide costs are huge: people don’t want to live in places with characteristics of a failed state. Nor do immigrants and tourists want to go to these places. Many people, indigenous and non-indigenous, are working hard to build sustainable communities in our northern regions, but it’s a huge ask to expect them to hang on when the rest of Australia offers safer and more satisfying lifestyles. And perhaps the greatest cost is the way the behaviour of these young people can stoke the fires of racism in reaction to their behaviour. Those who will promote a “no” case in the Voice referendum have plenty of vivid imagery to support their case.

The Four Corners program did no more than to touch on the social conditions leading to such destructive behaviour. The authors of the Conversation article mention “colonisation, such as intergenerational trauma, ongoing racism, discrimination, and unresolved issues related to self-determination”. These are all valid, but they are at a high level of generalization, and they provide no guidance about how to bring about better outcomes.

Another Conversation article by Faith Gordon of ANU argues convincingly about the need for a different approach: Diverting children away from the criminal justice system gives them a chance to ‘grow out’ of crime. She suggests a public health model “where diverse sectors such as health, social services, education, justice and policy work together to solve problems that contribute to violence and criminality including homelessness, addiction and family violence”.

There is nothing new in that, and as she points out it is the approach successfully used in other countries. What is striking, however, is that she feels compelled to make the same point that social researchers have been making for at least 50 years. It’s as if our policymakers are inoculated against the influence of evidence, or are entrapped by the inertia of dysfunctional systems.

The authors of the first Conversation article state that on average 4 695 young people are incarcerated at any time, most of them being Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander. They see this figure as strikingly high, but in terms of the damage they are causing, and in terms of the public resources committed to dealing with these young people, it suggests that a lot of cost is being incurred by a small number of young people. As the Four Corners program suggests, these are children with “severe behavioural problems”, who need “care, not jail”.

Unfortunately the phrase “care not jail” can be interpreted as a binary choice between detaining offenders and letting them run free, confirming the idea that reformers are soft on crime and are contemptuous of the community’s need for safety. Best practice in other countries does involve custodial detention, as pointed out by David McGuire of Diagrama, which runs youth custodial facilities in Spain. Without detention neither the objectives of community safety or rehabilitation are served.

Programs that treat these children with respect, that help them overcome their difficulties, that keep them meaningfully occupied, and that help them catch up with missed schooling, are labour-intensive and expensive, but so too is what we are doing at present.