Public policy

The government’s workplace legislation isn’t as scary as business lobbies make out

Clarity from someone who understands how it all works

Few Australians are old enough to remember the industrial strife of earlier times – the coal strike of 1949 when the Commonwealth (Labor) Government brought in troops to break the strike, the eight-month strike at Mount Isa mines in the 1960s, the King’s Cross strippers’ strike in 1979, or the waterfront strife of 1998, where the recently-departed Peter Reith established his reputation as an anti-union warrior.

Now the so-called employers’ groups and the Murdoch Media are warning us that those days will come again if the government gets its workplace legislation through the Senate. That legislation allows for modest forms of multi-employer bargaining. They don’t tell us how this industrial strife will come about: we are supposed to take it as a matter of faith that it will happen.

On last weekend’s Saturday Extra, long-time labour relations analyst John Buchanan clarified the issues by explaining the legislation’s main provisions.

For a start, the government will do nothing to undermine successful enterprise agreements.

He points out that there is already provision for multi-employer bargaining, but the problem is that it is administratively unworkable.

Buchanan explains the approach the government is using to improve the bargaining strength of the poorest-paid members of the workforce – cleaners, child-care workers, aged-care workers – who have been left behind in our industrial relations system. The legislation is designed to give them a chance to catch up with those who have done comparatively well in enterprise agreements. He explains other pathways to multi-employer bargaining which could be applied in sectors where union membership is low.

He acknowledges that there is wariness about the risk of wage-induced inflation, but he reminds us that inflation does not stem from the modest wage increases of the lowest paid.

He believes that there is a great deal of misunderstanding among those who voice their views on the issue of multi-employer bargaining. “There has been a lot of ideology here and very limited engagement with data”, he states, and he believes that our economic agencies don’t really understand how our wage-setting mechanisms work. It’s a complex system that has developed over 150 years, but in recent times, while it has served some workers well, it has let down the least unionised and generally least well-organized workers.

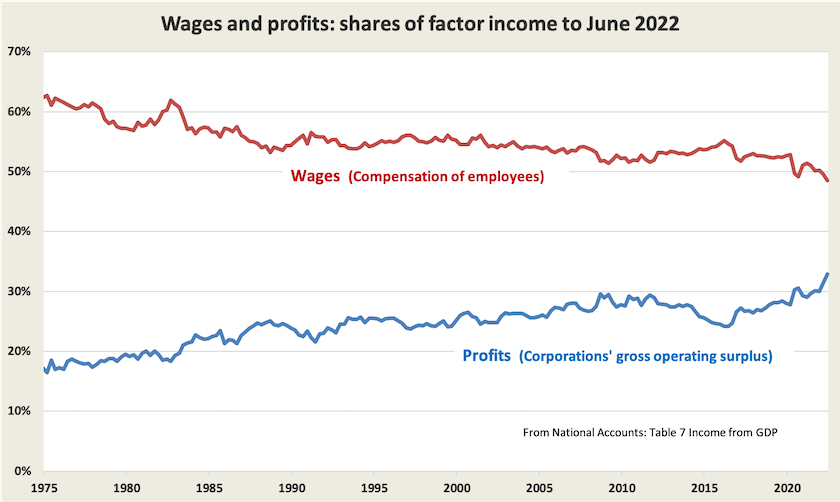

“We need a new way of thinking about how we share the gains of our prosperity” he says, but it will take time, many years, to bring back the share of wages and profits to reasonable proportions. (13 minutes)

As a reminder of Buchanan’s message about long-term trends, below is a chart of the wage and profit share of income, which I update every quarter and which last appeared in the roundup of September 10. Note both the long-term decline in labour’s share and its even sharper downturn in the last two years. The flip side of a lower share going to wages is a higher share going to corporations. Those corporations have amassed immense profits over recent years, providing their lobbies with well-stocked war chests to fight any campaign for fairer wage outcomes.

Collective bargaining is OK in other countries

The ABC business reporter Gareth Hutchens writes that The world is shifting to multi-employer bargaining. He draws our attention to a 2019 OECD report that signalled a shift from its previous emphasis on wage flexibility towards support for multi-employer bargaining. Multi-employer bargaining helps establish comparative wage justice, which is an issue not only in equity but also in economic efficiency, ensuring that workers can be allocated to where they can be most productive. Multi-employer bargaining can ensure that all employees, particularly those in small and medium-sized businesses, share in the benefits of economic growth.

What the OECD sees as a benefit – the inclusion of employees in small business – many Australian commentators see as a cost. “Small business”, a category that includes some quite large enterprises, has enjoyed a coddled existence in Australia, with weak enforcement of labour laws, concessional depreciation rates for capital equipment, payroll tax exemptions, and the capacity to avoid tax through family trusts. If they raise their wages some of the more poorly managed firms will go out of business, releasing resources for higher productivity activities. Some will put up prices, but is it a bad thing if the cost of fairer wages is passed through to consumers, including wealthy consumers living off investment returns?

Wages are rising for some, while others are left behind

There has been a 1.0 percent rise in the wage price index over the last quarter, the highest rise in at least the last ten years (but still lower than CPI inflation and therefore a fall in real terms). Wages have grown faster in the market-responsive private sector than in the public sector, and most of the rise has been by workers employed in individual arrangements which are largely outside the reach of wage-settling mechanisms.

Those who are covered by enterprise agreements have done reasonably well, but the laggards are those covered by awards.

By sector, retail trade has seen the strongest wage growth this quarter, a little clear of inflation, while the lowest wage growth has been in education and training. (So don’t be surprised if you encounter the person who used to be your child’s favourite teacher at your supermarket checkout.)

ABC business reporters Michael Janda and Rhiana Whitson have some comments on the wage price index: Wages make biggest jump in more than a decade, but public sector workers left behind.

Public opinion is on the government’s side

The latest Essential Report has a number of questions about the government’s industrial relations proposals. Respondents are generally enthusiastic about getting wages moving and giving power back to employees, although there are predictable differences between Coalition and Labor supporters, and young people are more enthusiastic about the changes than older people.

Respondents are most enthusiastic about “strengthening the power of lower paid workers to negotiate pay rises” (72 percent support), but almost as supportive of “giving workers the ability to join together across different workplaces to collectively negotiate pay rises” (62 percent support).

Who made the T-shirt you’re wearing?

Australia has a Modern Slavery Act designed to address human rights abuses along the supply line of clothing and other goods made in countries with low wages in labour-intensive manufacturing. It also covers exploitation of labour in Australian industries, such as horticulture, that employ migrant workers on temporary protection visas.

A coalition of human rights organisations and academics from the University of New South Wales has been monitoring companies’ adherence to the Act. In its report Broken Promises: Two years of corporate reporting under Australia’s Modern Slavery Act, it finds that two thirds of 92 companies sourcing products from sectors with known risks of slavery are still failing to comply with the basic reporting requirements specified under the Act, and that many companies are failing to take the effort to identify slavery risks in their supply lines. They are calling on the government to strengthen legislation covering modern slavery, with penalties for non-compliance

In each of four industries – horticulture, seafood, garments and gloves – the report ranks companies by their extent of compliance. Laxity in enforcing the Act places those companies that are abiding by the spirit of the legislation at a competitive disadvantage.

Universities back on the agenda – at last

Universities are still reeling from assaults inflicted by the Morrison government’s war on learning and scholarship – their deliberate exclusion from “Jobkeeper”, prohibitively high fees for humanities, and the neglect of foreign students stranded during Covid-19.

Education Minister Jason Clare has announced a broad inquiry into universities, covering funding, affordability, employment conditions, and ways in which universities and TAFEs can work together. Gwilym Croucher of the University of Melbourne explains the details in a Conversation contribution: The universities accord could see the most significant changes to Australian unis in a generation.

Croucher identfies “a confused and messy system for domestic student charges, an over reliance by the universities on international fee revenue and a politicised research grants scheme” as issues that must be addressed urgently.

How Australia goes to war

In our 121 years as a nation we have gone to war nine times. On only one of those occasions, as the Japanese advanced in 1941, has our engagement in a war been in response to a clear threat to our security.

Even though going to war is a serious business, on all of those occasions, ranging from Europe’s 1914-18 War, through to our long engagement in Afghanistan, the decision has been made by executive government.

An imminent threat?

In a little-publicized process, the Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade is conducting an Inquiry into international armed conflict decision-making.

On Late Night Live last Monday Phillip Adams interviewed Alison Broinowski (former diplomat and now President of Australians for War Powers Reform), and Chris Barrie (former Chief of the Defence Force) on the ways Australia goes to war. Their main concern is that these decisions are not made by Parliament.

They distinguish between situations where Australia may be in imminent and obvious danger (1941), and those where we may become involved for other reasons. In this latter category there can be a range of concerns, from formal treaties through to sentimental attachments to distant lands. In these situations they agree that the decision should be made by Parliament.

Parliamentary endorsement may not necessarily result in a different decision on employing soldiers, but at least those advocating our military involvement would have to articulate their reasons. As military scholars point out, unless the objective of armed conflict is clearly defined, great cost may be incurred with no meaningful outcome.

Broinowski and Barrie note that although the government has established this inquiry, it seems to have no interest in reforming the process.

Covid-19

The government’s weekly report of case numbers to November 15 shows a strong growth in reported cases. Deaths from or with Covid-19 are around 10 a day – this wave has arrested the decline in deaths but has not resulted in an increase in deaths. But in Norman Swan’s Coronacast he calls for us to take this wave seriously: Ok, now it's off and running - how do we slow it down?. Covid-19 has many nasty manifestations short of death.

There has been some small increase in people’s uptake of third and fourth dose vaccination, but our third and fourth-dose coverage is still low: 28 percent of people eligible for a third dose have not taken it up (the gap in Queensland is 35 percent).

It is notable that Covid mandates have emerged as an issue in the Victorian election. Last year the most intense libertarian and far-right anti-lockdown, anti-mask and anti-vaccination demonstrations were in Victoria.

Bitcoin has no clothes

“Trading in ‘assets’ with no underlying fundamental value on loosely regulated exchanges is always going to be a very risky endeavour. For many, it is likely to end in tears”.

So writes John Hawkins of the University of Canberra, commenting in The Conversation on the collapse of FTX, a major exchange for crypto currencies: The spectacular collapse of a $30 billion crypto exchange should come as no surprise.

Hawkins describes the business model underpinning FTX, as recounted by its majority owner. It “seems to rely heavily on funds injected by new investors, rather than on future returns based on the intrinsic value of the assets themselves”. To a financially unsophisticated aged blogger, that looks remarkably like a Ponzi scheme.

Hawkins’ main point is about the very nature of Bitcoin – its lack of attachment to any fundamental value. Bitcoin could never have made it to first base in a world where people understood the meaning of “wealth”, in particular the difference between those assets, tangible and intangible, that contribute to human welfare, and tokens that merely assign some fragile ordinal value to those assets.

Of course the gold standard of past years is subject to some of the same criticism, but gold has at least some use as a low resistance electrical conductor, as a filling for gangsters’ teeth, and as jewellery for show-offs. But the most meaningful currencies are those issued by responsible governments, backed by a nation’s real wealth.

Social media’s unsocial behaviour

We have weak rules restricting gambling advertisements on television. These rules are generally designed to limit young people’s exposure to advertisements during peak times, but there are no rules covering gambling on social media.

Writing in Open Forum Charles Livingstone alerts us to this lack of regulation: Gambling with our children’s future. Some social media outfits have their own restrictions, but these are not strong enough to protect young people from being lured into gambling.

While on the topic of social media, it is notable that the latest Essential Report has a section on Australians’ use of Twitter. It asks respondents how often they use Twitter as a source of news or social and political information. “Never” is the response of 62 percent of those surveyed, but young people are much heavier users of Twitter than older people: only 38 percent of those aged 18 to 34 say they “never” use Twitter. Among those who do use it as a source, Coalition supporters are the most faithful daily users.

In response to the proposition: “Twitter is a reliable source of information where people can trust the news and updates they receive”, 21 percent agree, 48 percent disagree. Almost two-thirds of those who actually use Twitter agree with that proposition, however. Older people are less trusting of Twitter than younger people.